Published online Feb 20, 2014. doi: 10.5321/wjs.v3.i1.10

Revised: November 11, 2013

Accepted: November 20, 2013

Published online: February 20, 2014

Processing time: 235 Days and 9.4 Hours

AIM: To evaluate a new therapeutic approach that may permanently address excessive involuntary muscle activity which causes temporomandibular disorders (TMD).

METHODS: A cohort of 69 TMD patients (33 men and 36 women, age range 14-71 years) was treated with Subconscious Temporomandibular Dysfunction (STeDy) therapy. A thick awareness splint assisted patients to gradually recognize the interdependence between psychological pressure and subconscious muscle activity. The STeDy therapy lasted for one year and involved three stages: (1) data collection including medical history, clinical examination and psychological evaluation; (2) application of the awareness splint and consultation on a monthly basis; and (3) final evaluation.

RESULTS: About 10% of patients (3 men and 4 women) quit the STeDy therapy within the first 3-6 mo due to severe health problems or psychosocial reasons. Based on the absence of objective and subjective clinical symptoms as well as on radiographic findings, the temporomandibular dysfunction treatment was successful in all remaining 62 patients that completed the year-long therapy. Symptoms, including recurrent headache, morning fatigue, clicking sound or painful temporomandibular joint disorders, were eliminated in all patients within the first six months. By completion of the STeDy therapy, all patients had learned to recognize stressful conditions and cognitively avoided displaying excessive bruxism or other subconscious activity of the stomatognathic muscles. A follow-up after at least one year indicated the permanent nature of the cognitive treatment in all patients, illustrating the fact that subconscious muscle activity due to stress plays a principal role in the great majority of TMD, at least in adults.

CONCLUSION: The STeDy therapy successfully and permanently resolved TMD problems of all patients that completed the year-long treatment.

Core tip: Despite the spectrum of variable symptoms, the pathology of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) is fundamentally a problem of excessive involuntary activity of certain stomatognathic muscles. The subconscious temporomandibular dysfunction (STeDy) therapy utilizes a thick awareness splint in order to gradually bring into the patient’s cognitive attention whatever stressful condition causes subconscious muscle activity. The STeDy therapy was applied for one year in 62 patients and successfully eliminated all TMD objective and subjective clinical symptoms as well as TMD-related radiographic findings. A follow-up after an additional year indicated the permanent nature of the cognitive treatment in all patients.

- Citation: Florakis A, Fotinea SE, Yapijakis C. Subconscious temporomandibular dysfunction therapy: A new therapeutic approach for temporomandibular disorders. World J Stomatol 2014; 3(1): 10-18

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6263/full/v3/i1/10.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5321/wjs.v3.i1.10

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) include a wide spectrum of acute and chronic problems of the joints of the mandible and temple bones, as well as the head and neck muscles[1-9]. Due to the use of different clinical criteria, the prevalence of TMD varies extremely between 6% and 93% in the literature[1-11]. A range of biological, psychological and social etiologies comprise genetic factors which influence skeletal anatomy or central and peripheral (orofacial) nervous system dysfunction, as well as nutritional deficits, allergies, personality type, stress, dental or medication treatments[3,6,12-22].

A common major symptom of TMD is bruxism, i.e., the involuntary, subconscious and excessive grinding and/or clenching of the upper and lower teeth which may occur either in sleep or when awake[16,23,24]. There are multiple causes of bruxism, stress being the most obvious. In this light, it is hardly surprising that bruxism is a pervasive pattern of behavior which affects a significant percentage of the general population[23-25].

Common treatment of TMD with oral appliances used to be based on the biased assumptions that they facilitated occlusal disengagement, relaxed jaw musculature, repositioned temporomandibular joints, and restored vertical occlusion dimension[14,15,23-27]. In recent years, advances in neuroscience and pain pathophysiology have underlined the notion that treatments which involve oral appliances, as well as other methods such as biofeedback devices, exert their effect mainly as elaborate placebos[14,23,28,29]. It is generally considered that conservative and reversible treatments are more acceptable than aggressive interventions, such as surgical removing of a masseter section[14]. Nevertheless, most treatments with oral appliances focus on treating symptoms and, although they frequently produce immediate positive subjective responses, they prove ineffective on a permanent basis since they do not address the causes[14,23,24,30].

We present here a new therapeutic approach which aims to permanently address the causes of TMD. Despite the wide spectrum of variable symptoms, TMD pathology is essentially a problem of excessive involuntary activity (“hyperfunction”) of certain stomatognathic muscles, observed unexpectedly and for no immediately apparent reason. We define this involuntary muscle activity underlying all TMD as subconscious temporomandibular dysfunction (STeDy).

The scope of the proposed STeDy therapy is to bring into the patient’s cognitive attention whatever causes the subconscious involuntary muscle activity. This is achieved through the use of a rather thick acrylic oral appliance (“awareness” splint), which alerts the patient when he/she clenches his/her teeth and even wakes him/her if asleep. Sleep bruxism often applies powerful forces on teeth, gums and joints, exerting up to three times the force normally applied during food chewing[27,31].

We present the methodology of the STeDy therapy and some illustrative cases treated with this approach. In addition, we discuss the permanent effects of the therapy on TMD symptoms after a follow-up period of at least one year.

A total of 69 Greek patients (33 men and 36 women) participated in this study after giving informed consent. All patients were residents of the Athens metropolitan area. Their age ranged between 14 and 71 years (47 ± 11.7 years, median 49 years). The diagnosis of TMD was made according to Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD) axis I[32]. The patients were informed that the STeDy therapy is an innovative methodology and its effectiveness was under investigation. The clinical study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Athens Medical School.

The STeDy therapy occurs in three stages. The first (preliminary) stage involves one interview appointment of data collection, which includes questionnaire answering, medical history taking, clinical examination and psychological evaluation, as well as consultation on oral hygiene and description of the STeDy therapy. The second (therapeutic) stage lasts about one year, involving initial preparation and application of the awareness splint as well as consultation and evaluation appointments on a monthly basis. The third (final evaluation) stage involves follow-up and occurs one year after the initiation of the therapy and every year after that. It is very helpful to audio-tape or video-record discussions during sessions, so that a more accurate and objective account of a patient’s psychological status is available and, therefore, assessment of the therapy progression may be facilitated.

Medical history taking may reveal health or psychosocial conditions which are usually associated with TMD. A panoramic radiograph may reveal abnormal periodontal space, an indication of possible STeDy. The patient is asked to fill out a questionnaire. Each question is clarified by explanations which help the patient to realize the nature of the damage caused by the subconscious pressures exerted on teeth, tongue or orofacial muscles and the related dysfunctions of the stomatognathic system. Examples of questions and explanations in parentheses follow: (1) Do you have recurrent headache (If the headache is usually experienced in the temporal area, this is indication for inflammation of the temporalis, a muscle which assists chewing. This type of headache, usually a migraine, is called tension headache); (2) Do you feel tired when you wake up in the morning [This may indicate increased temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function during night sleep]; (3) Do you hear a “sound” or “noise” from the temporomandibular joint area when chewing or yawning (The clicking sound indicates dislocation of the mandible, an advanced problem of the TMJ. Possible sources are clenching and/or teeth grinding); and (4) Do you experience annoyance/pain in your ears (A painful inflammation of the TMJ is perceived by most people as ear annoyance or pain).

The patient responds to each question by selecting among preset numeric values of 0-3, as follows: no, never (0); rarely (1); often (2); very often or continuously (3). This allows both qualification of the nature and quantification of the degree of TMJ involvement and possible STeDy in each patient.

Indications of possible STeDy include: (1) the existence of malocclusion, especially when there is pain in apparently healthy teeth in conjunction with radiographic findings; (2) intense abrasion and wear of teeth, as well as mobility or peculiar drift of teeth; (3) presence of gingivitis or longstanding periodontitis despite good oral hygiene and absence of systemic diseases; (4) imprints on cheek mucosa and/or tongue; (5) orofacial muscles such as the temporalis, the masseter, the pterygoid and the digastric being painful on touch; and (6) any symptoms of TMJ dysfunction, such as clicking, painful palpation and displacement during the depression of the mandible. At this stage, any existing premature contacts are eliminated.

During data collection, the personality and psychological status of the patient is evaluated and recorded. Consultation on specific oral hygiene issues and discussion regarding the STeDy therapy are in order. The patient is asked to follow the oral hygiene guidelines for 2 wk.

If the patient’s periodontal disorder has been in regression two weeks after the elimination of premature contacts, this is another indication of STeDy. Upon the patient’s informed consent, treatment is initiated.

The awareness splint, which is, in essence, a thick flat plane stabilization appliance, is fabricated at chairside. Its thickness allows the full extent of occlusal pressure forces of the patient’s orofacial muscles. The splint thickness depends on the patient’s interocclusal rest space since the splint is made as thick as that space plus 3 mm. Therefore, if an interocclusal rest space is 2-4 mm, a splint of 5-7 mm thick is fabricated. The awareness splint allows one to exercise pressure forces, while at the same time one may consciously feel and understand the impact of those forces. It is worth mentioning that the damage caused by these forces is negligible as in any movement of the lower jaw, all teeth are in contact with the splint so that the pressure exercised is equally distributed. In patients with bruxism, the tooth enamel during grinding is facing acrylic, while the TMJ “receives” pressure forces in a position, which by default, is considered already designed to “withstand” them.

Application of the awareness splint is accompanied with a discussion with patient about its features and function. Detailed instructions are given to wear the splint over night sleep and during daytime when the patient is under stress, if feasible (e.g., when driving in traffic). One week later, there is re-evaluation of the smooth functionality of the splint.

Ten sessions take place on a monthly basis, in which consultation in the form of friendly discussion as well as evaluation of the patient’s awareness occurs. During this period, the patient is advised to perform various anti-stress exercises, such as a procedure to frequently check the possible tension of the jaw (in which the head is supported by one’s thumb while the rest of the fingers check the jaw tightness and relaxation of the lower lip sphincter muscle), breathing exercises (relaxed breathing during which the end of the lips vibrate with exhaling), or even the use of an anti-stress ball. It is also suggested that hard gum mastication (e.g., Chios mastic) is appropriate when the patient experiences tension, in order to avoid grinding by merely immersing the teeth in the gum mass. Last but not least, consumption of a natural tranquilizer such as camomile or valerian tea is also suggested prior to night sleep.

During the period of monthly sessions, the patient’s progress in respect to STeDy therapy is being closely monitored. The aim of this evaluation is to see whether the patient gradually displays consciousness: (1) to recognize STeDy symptoms when felt (cognitive level); (2) to be aware of the interdependence between psychological pressure and STeDy along with personal injuries caused by this dysfunction (psychomotor level); (3) to obtain conscious control over jaw movements by taking personal responsibility to plan and implement the changes necessary to achieve self-regulation and to transform tension into something more creative (cognitive level); and (4) to obtain a more positive attitude towards life and to be encouraged to manage changes in one’s life (emotional level).

The final evaluation occurs one year after initiation of the STeDy therapy. A treatment is considered successful if two objective and three subjective criteria are fulfilled. The objective factors include the absence of clinical symptoms and radiographic findings. In addition, the therapy is successful if the patient: (1) declares that all STeDy symptoms have vanished; (2) is fully conscious of the cause of STeDy (as mentioned above); and (3) knows how to prevent STeDy when sometime in the future there is a period of distress in his/her life. In case the above criteria are not fulfilled, the therapy may be continued for a few more months. After a successful STeDy therapy, there is follow-up once a year in order to ensure the permanent nature of the treatment.

About 10% of patients (3 men and 4 women) did not complete the year-long STeDy therapy, but instead quit within the first 3-6 mo for various reasons. Four of them quit due to severe health problems (three developed cancer and one suffered a myocardial infarction) and the rest quit due to psychosocial reasons (an example is Case 3 as described below).

The STeDy therapy was received well by all remaining patients who completed the year-long treatment. The temporomandibular dysfunction treatment was successful in all 62 patients, based on the five criteria mentioned above, which include absence of objective and subjective clinical symptoms, as well as of radiographic findings.

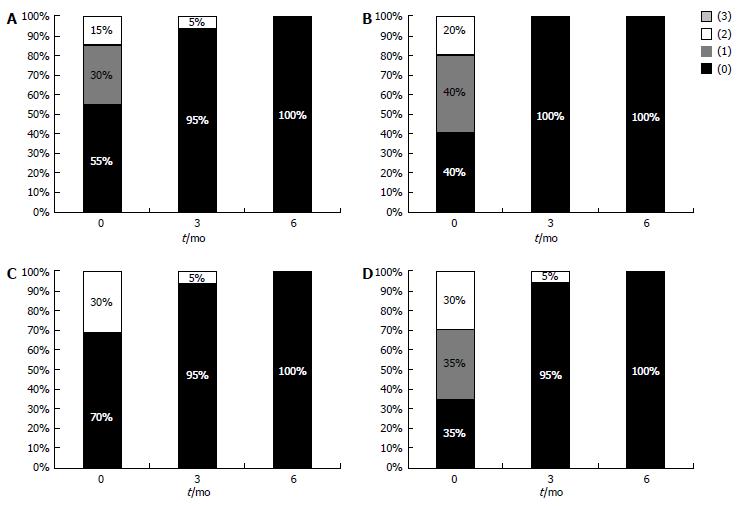

Before treatment, the 62 patients had reported the following subjective symptoms (Table 1, Figure 1): (1) Recurrent headache: 55% never had any, 30% rarely had some, and 15% often had some; (2) Morning tiredness: 40% never had any, 40% rarely had some, and 20% often had some; (3) Clicking sound: 70% never had any, 0% rarely had some, and 30% often had some; and (4) Painful TMJ: 35% never had any, 35% rarely had some, and 30% often had some.

| Questions | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Recurrent headache | Initially | 34 | 19 | 9 | 0 |

| At 3 mo | 59 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| At 6 mo | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Morning tiredness | Initially | 25 | 25 | 12 | 0 |

| At 3 mo | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| At 6 mo | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Clicking sound | Initially | 44 | 0 | 18 | 0 |

| At 3 mo | 59 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| At 6 mo | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Painful TMJ | Initially | 22 | 22 | 18 | 0 |

| At 3 mo | 59 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| At 6 mo | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

One third of the patients (n = 22) had two of the aforementioned severe symptoms, one third (n = 21) had only one severe symptom, while another one third (n = 19) did not report any such symptoms but had other ones like painful muscles. Significant improvement was subjectively evident in the first three months, while within six months, all subjective symptoms were eliminated (Table 1, Figure 1). A follow-up after at least one year has indicated the permanent nature of the treatment in all patients.

In order to illustrate the effect of the STeDy therapy approach, a couple of characteristic cases which completed the year-long treatment will be described. In addition, a third case of one of the quitters will follow.

Case 1: A 54-year-old lady married with two adult sons and very introverted. She used to work as a bank financial officer but retired early. A couple of months after having new prosthetic work in teeth 16 and 26, she complained about morning headache, annoyance in ears and dental pain during mouth washing and chewing. She also had a painful temporalis. She considered the headaches as almost “natural” because her mother and her aunt frequently suffered from them as well.

It took approximately seven months before the patient decided to be treated with the STeDy therapy. After two months of treatment, she presented with strong morning headache and dental pain. Discussion brought up the stress she felt at the time because of her younger son’s problems with university studies. She was recommended to keep a diary of stressful days and adopt a more relaxed body posture. At six months she stated that she understood that she was tense, had been following the anti-stress exercises and had been more extraverted and friendly with people. At seven months, her mouth and posture were more relaxed. Starting at eight months, she started to avoid wearing the awareness splint one day per week. At ten months, the patient said she did not have any STeDy symptoms because she felt more relaxed and open-minded than previously. She felt that if she might need the splint again in case of stress, she would know how to use it. The first yearly follow-up showed that she rarely needed to wear the splint.

Case 2: A 49-year-old plump man, kind-natured and timid, married with two daughters studying at university. He had a degree in economics and worked as a chief accounting manager in a big corporation. He complained about jaw stiffness and fatigue in the morning. He knew that he clenched his teeth and that he had bloody gingivae and TMJ clicking. The clinical examination revealed painful right outer pterygoid and right masseter muscles, as well as painful palpation and light clicking of left TMJ.

The patient decided without hesitation to be treated with STeDy therapy. After one month of treatment, he claimed that with the awareness splint, his morning taste was much better and he woke up with a sense of freshness in his mouth. In the second month, the patient reported that he did not sleep well and that his teeth were bloody two mornings in a row during a very stressful period of the fiscal year end. Psychological consultation underlined the fact that stress resulted in actual physical damage and he was recommended to keep a diary of stressful days. The patient seemed to understand that he had to overcome stress in order to help himself. In the third month, he reported that he did not feel any pain in the morning and he seemed very relaxed, extraverted and joyful. During discussion, he became sad when he mentioned that he missed his deceased parents, especially in holiday banquets. A few minutes later, the same sadness reappeared when the patient talked about the absence of his daughters from the family home during holidays. Consultation focused on the need to accept the facts of life and to always try to stay calm, almost as an independent observer, even when stressful moments arise.

In the fourth month, the patient reported that he had realized how little things caused disproportionately much stress and pain to him. This had happened when he did not find a free tennis court when he wanted to play with a friend and that made him distressed and put him under pressure for the whole day while trying to conceal his frustration. In the fifth month, he reported that he was very calm during the death of two relatives in advanced age, one of whom was a dear uncle (his “second father”). In the next couple of months, the patient reported that he had a couple of problems in his job, the first of which caused him painful teeth clenching, while the second one he faced humorously without feeling stress. He was advised to avoid wearing the awareness splint two days per week.

In the eighth month, the patient appeared to be very serene and all STeDy symptoms seemed to have disappeared. He reported that he did not observe any difference in the mornings when he had not worn the splint. He even mentioned a remarkable incident in his workplace. A misallocation of a huge amount of money in a bank account had occurred and the corporate director in a state of panic went to find him in the company dining room in order to tell him to work immediately on the problem. Reportedly, the patient replied calmly to his director that “anxiety creates more problems” and that “lunchtime was a sacred right and that he would tackle the problem after his meal in about a quarter of an hour”! Indeed, the patient worked out a solution soon afterwards. At nine and ten months, the patient said he did not have any STeDy symptoms because he felt no difference if he wore the splint or not. The clinical and radiological examination did not reveal any TMD symptoms. The first yearly follow-up also showed no STeDy findings.

Case 3: A 20-year-old university student was referred by a dentist because of bruxism during sleep. The clinical examination revealed painful right outer pterygoid, masseter and digastric muscles. In addition, the patient presented with several red spots on his face, mild alopecia, bitten nails and a childish voice tone. He confirmed that from time to time he underwent treatment for alopecia and that the red spots appeared when he was anxious.

Approximately one week after the initiation of the STeDy therapy, he started waking up relaxed in the morning without any painful TMD symptoms. In the first month he stated that he felt calm, an obvious fact since his appearance had changed drastically. His red spots had disappeared and he remarked that his hair had stopped falling out.

In the third month, the casual discussion about the patient’s anxieties revealed that he felt a chronic fear about his father who used to beat him brutally when he was a child. When it was suggested to him that it was possible that the cause for his main anxiety might be his father’s oppression and that he had to face that, the patient was deeply disturbed. After that session, the patient decided to quit the STeDy therapy.

We present here a new therapeutic approach of various TMD symptoms, which are caused by excessive involuntary muscle activity. The Subconscious Temporomandibular Dysfunction (STeDy) therapy utilizes an awareness splint in order to bring into the patient’s cognitive attention whatever causes bruxism or other subconscious muscle activity.

The STeDy therapy was successful in all 62 patients that completed the year-long treatment, based on the absence of subjective and objective clinical TMD symptoms. This treatment faced both dental and psychological problems of all patients in a permanent manner, as indicated by a follow-up one year after its completion. The surprisingly optimal success of the STeDy therapy illustrates the fact that stress plays a principal role in the great majority of TMD, at least in adults, regardless of variable clinical symptoms[1-11,14,33-42].

The optimal success of the STeDy therapy, especially in comparison to other treatment using oral appliances[43-48], illustrates the substantial difference of the awareness splint with other splint types. Excessive grinding and clenching of teeth is a form of tension elimination which the patient does not realize with other occlusal appliances which are designed to reduce muscle activity and loading of temporomandibular joints. On the other hand, with the awareness splint, the patient is forced to consciously feel the biting pressure that he/she exercises and gradually notices its correlation with certain stressful causes. As this realization takes time, approximately one year of treatment and coaching is probably needed, although in this study most subjective STeDy symptoms had vanished within six months. Once the patient realizes that certain stressful conditions may cause temporomandibular dysfunction, he/she may use the awareness splint as a precautionary measure whenever he/she feels vulnerable. Therefore, the STeDy therapy seems to have a permanent effect on the patient.

There are several skills which a dentist applying the STeDy therapy must possess. These include: (1) fair knowledge of head anatomy for palpating the stomatognathic system muscles; (2) ability to differentially diagnose gingivitis related to TMD or other causes; (3) ability to interpret radiographic findings; and (4) knowledge of psychology in order to recognize stress-related emotional conditions, to discuss with the patient how to deal with daily problems and how stressful situations affect his/her tooth bruxism. In addition, the dentist must be able to recognize psychotic cases which will need to be referred to a psychiatrist.

There are certain mistakes that should be avoided during the STeDy therapy. Before any such treatment, it is obvious that all serious dental problems such as painful occlusion due to pulpitis, periodontitis and hardship have to be addressed first. In addition, if the awareness splints are made without using adjustable or semi-adjustable anatomic articulators but common articulators instead, then there is considerable pressure on the molars and, during elimination of premature contacts, the splint height is reduced.

It should be mentioned that the STeDy therapy has to be modified in some cases. For instance, when several teeth are missing and prosthetic work is in order, it is advised to first use a bite splint in order to temporarily address the TMD symptoms. After the completion of the prosthetic treatment, STeDy therapy may be realized using an awareness splint. Another example is the modification of part of the palatal side of the awareness splint in patients who feel discomfort due to the perceived threat of foreign body. In this case, the splint may be tolerable if it covers the palatal sides of the upper teeth as well as part of the palate.

The STeDy therapy addresses the main cause of TMD, which is related and/or aggravated by stress. There is mounting evidence that a strong psychological element underlies etiologies of TMD[1-3,6,18,19,21,22,35-38,48-53]. This fact might explain the reported evidence indicating that cognitive behavioral therapy either alone or in combination with biofeedback, conservative treatment or self-care may improve the outcomes of TMD patients[54].

The relative success of psychological approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy or placebo treatments[14,54] and the fact that the STeDy therapy seems to have optimal success underline the fact that a radically effective treatment for TMD essentially needs a long-term management of stress. Stress is a common unconscious defense mechanism to the underlying fear of death and the best way to face it according to cognitive psychology is to recognize its irrationality[55,56].

This method of bringing into a person’s attention the irrationality of stress and unsubstantiated fears in everyday life (including the constant fear of death) stems from the teachings of the Athenian philosopher Epicurus[55-57]. He maintained that in order for someone to live a happy life, one has to consciously recognize the irrational anxieties and prudently avoid psychological suffering with all its negative consequences[40,41]. It seems that the same stands for TMD treatment as well as for many other stress-related disorders. Specialized health professionals may help their patients more effectively by showing them the way to consciously avoid the causes than by treating temporarily or only masking the apparent symptoms.

In conclusion, the STeDy therapy assisted all patients to recognize stressful conditions and cognitively avoid excessive bruxism or other subconscious activity of stomatognathic muscles. A follow-up after at least one year indicated the permanent nature of this cognitive approach, illustrating the fact that subconscious muscle activity due to stress plays a principal role in the great majority of TMD, at least in adults.

The authors wish to thank all patients who participated in this study.

Despite the spectrum of variable symptoms, the pathology of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) is fundamentally a problem of excessive involuntary activity of certain stomatognathic muscles. The subconscious temporomandibular dysfunction (STeDy) therapy utilizes a thick awareness splint in order to gradually bring into the patient’s cognitive attention whatever stressful condition causes subconscious muscle activity.

TMD includes a wide spectrum of acute and chronic problems of the joints of mandible and temple bones as well as the head and neck muscles. Due to the use of different clinical criteria, the prevalence of TMD varies extremely between 6% and 93% in the literature.

The authors present here a new therapeutic approach of various TMD symptoms which are caused by excessive involuntary muscle activity.

The STeDy therapy was applied for one year in 62 patients and successfully eliminated all TMD objective and subjective clinical symptoms as well as TMD-related radiographic findings. A follow-up after an additional year indicated the permanent nature of the cognitive treatment in all patients.

This manuscript submitted by Dr. Florakis gives some useful information on treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders. It provides a useful treatment suggestion on subconscious temporomandibular dysfunction.

P- Reviewers: Lucinei O, Nikgoo A, Santos FA, Zhong LP S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Gonçalves DA, Dal Fabbro AL, Campos JA, Bigal ME, Speciali JG. Symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in the population: an epidemiological study. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:270-278. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Poveda Roda R, Bagan JV, Díaz Fernández JM, Hernández Bazán S, Jiménez Soriano Y. Review of temporomandibular joint pathology. Part I: classification, epidemiology and risk factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E292-E298. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lee LT, Yeung RW, Wong MC, McMillan AS. Diagnostic sub-types, psychological distress and psychosocial dysfunction in southern Chinese people with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:184-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Köhler AA, Helkimo AN, Magnusson T, Hugoson A. Prevalence of symptoms and signs indicative of temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents. A cross-sectional epidemiological investigation covering two decades. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10 Suppl 1:16-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Toscano P, Defabianis P. Clinical evaluation of temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:188-192. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yap AU, Dworkin SF, Chua EK, List T, Tan KB, Tan HH. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder subtypes, psychologic distress, and psychosocial dysfunction in Asian patients. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17:21-28. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Nilsson IM. Reliability, validity, incidence and impact of temporormandibular pain disorders in adolescents. Swed Dent J Suppl. 2007;7-86. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kostrzewa-Janicka J, Mierzwinska-Nastalska E, Jurkowski P, Okonski P, Nedzi-Gora M. Assessment of temporomandibular joint disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;788:207-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Reiter S, Goldsmith C, Emodi-Perlman A, Friedman-Rubin P, Winocur E. Masticatory muscle disorders diagnostic criteria: the American Academy of Orofacial Pain versus the research diagnostic criteria/temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD). J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:941-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Emshoff R, Rudisch A. Validity of clinical diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: clinical versus magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of temporomandibular joint internal derangement and osteoarthrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Galhardo AP, da Costa Leite C, Gebrim EM, Gomes RL, Mukai MK, Yamaguchi CA, Bernardo WM, Soares JM, Baracat EC, Gil C. The correlation of research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders and magnetic resonance imaging: a study of diagnostic accuracy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:277-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cairns BE. Pathophysiology of TMD pain--basic mechanisms and their implications for pharmacotherapy. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:391-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bouloux GF. Temporomandibular joint pain and synovial fluid analysis: a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2497-2504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Klasser GD, Greene CS. Oral appliances in the management of temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:212-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McNeill C. Management of temporomandibular disorders: concepts and controversies. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;77:510-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nissani M. A bibliographical survey of bruxism with special emphasis on non-traditional treatment modalities. J Oral Sci. 2001;43:73-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de Souza RF, Lovato da Silva CH, Nasser M, Fedorowicz Z, Al-Muharraqi MA. Interventions for the management of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD007261. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Pizolato RA, Freitas-Fernandes FS, Gavião MB. Anxiety/depression and orofacial myofacial disorders as factors associated with TMD in children. Braz Oral Res. 2013;27:156-162. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Fernandes G, Franco AL, Gonçalves DA, Speciali JG, Bigal ME, Camparis CM. Temporomandibular disorders, sleep bruxism, and primary headaches are mutually associated. J Orofac Pain. 2013;27:14-20. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Koutris M, Lobbezoo F, Sümer NC, Atiş ES, Türker KS, Naeije M. Is myofascial pain in temporomandibular disorder patients a manifestation of delayed-onset muscle soreness. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:712-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dougall AL, Jimenez CA, Haggard RA, Stowell AW, Riggs RR, Gatchel RJ. Biopsychosocial factors associated with the subcategories of acute temporomandibular joint disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2012;26:7-16. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Reissmann DR, John MT, Schierz O, Seedorf H, Doering S. Stress-related adaptive versus maladaptive coping and temporomandibular disorder pain. J Orofac Pain. 2012;26:181-190. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Klasser GD, Greene CS, Lavigne GJ. Oral appliances and the management of sleep bruxism in adults: a century of clinical applications and search for mechanisms. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:453-462. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Ellison JM, Stanziani P. SSRI-associated nocturnal bruxism in four patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:432-434. [PubMed] |

| 25. | da Silva Junior AA, Krymchantowski AV, Gomes JB, Leite FM, Alves BM, Lara RP, Gómez RS, Teixeira AL. Temporomandibular disorders and chronic daily headaches in the community and in specialty care. Headache. 2013;53:1350-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Spencer J, Patel M, Mehta N, Simmons HC, Bennett T, Bailey JK, Moses A. Special consideration regarding the assessment and management of patients being treated with mandibular advancement oral appliance therapy for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Cranio. 2013;31:10-13. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Hannam AG, De Cou RE, Scott JD, Wood WW. The relationship between dental occlusion, muscle activity and associated jaw movement in man. Arch Oral Biol. 1977;22:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ferrando M, Galdón MJ, Durá E, Andreu Y, Jiménez Y, Poveda R. Enhancing the efficacy of treatment for temporomandibular patients with muscular diagnosis through cognitive-behavioral intervention, including hypnosis: a randomized study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Manfredini D, Castroflorio T, Perinetti G, Guarda-Nardini L. Dental occlusion, body posture and temporomandibular disorders: where we are now and where we are heading for. J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:463-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Resende CM, Alves AC, Coelho LT, Alchieri JC, Roncalli AG, Barbosa GA. Quality of life and general health in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Braz Oral Res. 2013;27:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gallo LM, Guerra PO, Palla S. Automatic on-line one-channel recognition of masseter activity. J Dent Res. 1998;77:1539-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wahlund K, List T, Dworkin SF. Temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents: reliability of a questionnaire, clinical examination, and diagnosis. J Orofac Pain. 1998;12:42-51. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Olivo SA, Fuentes J, Major PW, Warren S, Thie NM, Magee DJ. The association between neck disability and jaw disability. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:670-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Salé H, Hedman L, Isberg A. Accuracy of patients’ recall of temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction after experiencing whiplash trauma: a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:879-886. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Nilsson IM, List T, Drangsholt M. The reliability and validity of self-reported temporomandibular disorder pain in adolescents. J Orofac Pain. 2006;20:138-144. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Franco AL, Gonçalves DA, Castanharo SM, Speciali JG, Bigal ME, Camparis CM. Migraine is the most prevalent primary headache in individuals with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:287-292. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Lupoli TA, Lockey RF. Temporomandibular dysfunction: an often overlooked cause of chronic headaches. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:314-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kevilj R, Mehulic K, Dundjer A. Temporomandibular disorders and bruxism. Part I. Minerva Stomatol. 2007;56:393-397. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Al-Ani Z, Gray R. TMD current concepts: 1. An update. Dent Update. 2007;34:278-280, 282-284, 287-288. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Alstergren P, Fredriksson L, Kopp S. Temporomandibular joint pressure pain threshold is systemically modulated in rheumatoid arthritis. J Orofac Pain. 2008;22:231-238. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Ohrbach R. Disability assessment in temporomandibular disorders and masticatory system rehabilitation. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:452-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Limchaichana N, Nilsson H, Ekberg EC, Nilner M, Petersson A. Clinical diagnoses and MRI findings in patients with TMD pain. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34:237-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Landry-Schönbeck A, de Grandmont P, Rompré PH, Lavigne GJ. Effect of an adjustable mandibular advancement appliance on sleep bruxism: a crossover sleep laboratory study. Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:251-259. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Macedo CR, Silva AB, Machado MA, Saconato H, Prado GF. Occlusal splints for treating sleep bruxism (tooth grinding). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17:CD005514. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Saueressig AC, Mainieri VC, Grossi PK, Fagondes SC, Shinkai RS, Lima EM, Teixeira ER, Grossi ML. Analysis of the influence of a mandibular advancement device on sleep and sleep bruxism scores by means of the BiteStrip and the Sleep Assessment Questionnaire. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:204-213. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Christidis N, Smedberg E, Hägglund H, Hedenberg-Magnusson B. Patients’ experience of care and treatment outcome at the Department of Clinical Oral Physiology, Dental Public Service in Stockholm. Swed Dent J. 2010;34:43-52. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Dubé C, Rompré PH, Manzini C, Guitard F, de Grandmont P, Lavigne GJ. Quantitative polygraphic controlled study on efficacy and safety of oral splint devices in tooth-grinding subjects. J Dent Res. 2004;83:398-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Clark GT, Baba K, McCreary CP. Predicting the outcome of a physical medicine treatment for temporomandibular disorder patients. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23:221-229. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Nilsson AM, Dahlström L. Perceived symptoms of psychological distress and salivary cortisol levels in young women with muscular or disk-related temporomandibular disorders. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Dahlström L, Carlsson GE. Temporomandibular disorders and oral health-related quality of life. A systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Karibe H, Goddard G, Kawakami T, Aoyagi K, Rudd P, McNeill C. Comparison of subjective symptoms among three diagnostic subgroups of adolescents with temporomandibular disorders. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:458-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Barros Vde M, Seraidarian PI, Côrtes MI, de Paula LV. The impact of orofacial pain on the quality of life of patients with temporomandibular disorder. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23:28-37. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Nilsson IM, Drangsholt M, List T. Impact of temporomandibular disorder pain in adolescents: differences by age and gender. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23:115-122. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Aggarwal VR, Tickle M, Javidi H, Peters S. Reviewing the evidence: can cognitive behavioral therapy improve outcomes for patients with chronic orofacial pain. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:163-171. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Yalom ID. Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the terror of death. Jossey-Bass Publishing. 2008;36:283-297. |

| 56. | Strenger C. Mild Epicureanism: notes toward the definition of a therapeutic attitude. Am J Psychother. 2008;62:195-211. [PubMed] |