Published online Nov 20, 2013. doi: 10.5321/wjs.v2.i4.97

Revised: August 22, 2013

Accepted: September 3, 2013

Published online: November 20, 2013

Processing time: 195 Days and 2.7 Hours

Oral cancer treatment primarily focused on the surgical removal of cancer tissues followed by surgical/prosthetic reconstruction. Restoration of the missing structures immediately after surgery shortens recovery time and allows patient to return to community as a functioning member. The most practiced surgical obturators are simple resin prosthetic bases without incorporation of the teeth. This article highlights a technique to fabricate a surgical obturator that duplicates patient’s original tissue form including teeth, alveolus and palatal tissues. The obturator is placed immediately after surgery and make patient feel unaware of surgical deformity. The obturator prosthesis fabricated with this technique supports soft tissues and minimizes the scar contracture. We have clinically tried this technique in 11 patients. Patients’ satisfaction level was recorded on visual analogue scale (VAS) and it ranges between 74% and 94% (with average of 87%). Four different prosthodontists have visually evaluated facial asymmetry of patients at 6 mo recall and their average perception on VAS varies between 71% and 93% (with average of 84%).

Core tip: This article highlights a technique to fabricate a surgical obturator that duplicates patient’s original tissue form including teeth, alveolus and palatal tissues. Make patient feel unaware of surgical deformity. The obturator prosthesis fabricated with this technique supports soft tissues and minimizes the scar contracture. We have clinically tried this technique in 11 patients. Patients’ satisfaction level was recorded on visual analogue scale (VAS) and it ranges between 74% and 94% (with average of 87%). Four different prosthodontists have visually evaluated facial asymmetry of patients at 6 months recall and their average perception on VAS varies between 71% and 93% (with average of 84%).

- Citation: Patil PG. Surgical obturator duplicating original tissue-form restores esthetics and function in oral cancer. World J Stomatol 2013; 2(4): 97-102

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6263/full/v2/i4/97.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5321/wjs.v2.i4.97

Treatment of oral cancer necessitates surgical removal of the affected maxillofacial hard and soft tissues[1]. Loss of structural continuity affects esthetic appearance and functional performance like mastication and swallowing[2]. Esthetic disfigurement significantly affects patients’ social and psychological wellbeing[3]. In addition to local and general health psychological, social and economic aspects determine final treatment outcome of the prosthetic rehabilitation[2]. Patient may get disease free after resection of the cancer tissues but can become a permanent handicap if not rehabilitated in a proper manner. Plastic surgeons face great challenges to reconstruct oral and maxillofacial defects to maintain the functional integrity and esthetic appearance especially in large sized defects and trismus. In case of malignancies, radiotherapy is a vital parameter in controlling neck metastasis. Though surgical reconstruction restores the defect, replacement of teeth and facial tissue support can only be achieved by prosthodontic reconstruction. Obturators are given to maintain an artificial barrier between nasopharynx and oropharynx so that oral intake of food should not be regurgitated from the nose and sufficient negative pressure develops in the oral cavity to facilitate deglutition[1]. Depending upon the time of prosthesis given they are classified as immediate surgical (immediate), delayed surgical (7-10 d), interim (4-6 wk) and definitive (After 4-6 mo) obturators[1,4].

Immediate or delayed surgical obturator minimizes scar contracture and disfigurement thereby making a positive effect on the patients’ psychology. Various designs have been proposed for fabrication of the surgical obturator. The design ranges from acrylic resin record base bearing no teeth[5]. With or without wrought-wire clasps[6], to a clasped acrylic resin prosthesis that restores the dental arch form[7]. Dentate patients are relatively easier to treat than edentulous patients as maximum retention and stability can be achieved from remaining teeth. The most practiced surgical obturator is a simple resin prosthetic base without incorporation of teeth. Addition of teeth in initial healing phase may cause constant source of irritation and hamper healing process according to many authors. However only anterior teeth can be restored until surgical wound is healed in some clinical situations[1,8]. In case of radiotherapy, the tissues become more friable and vulnerable hence the simplest form of prosthesis is advocated in most of the clinical situations[3].

This article highlights a treatment concept which restores resected maxillofacial tissues with a surgical obturator that duplicates patient’s original tissue form[9,10]. The technique is developed in our hospital and total 11 cancer patients were treated in last 2 years. Patients were evaluated for patients’ satisfaction level and clinicians’ perception for bilateral facial symmetry on visual analogue scale (VAS) at 6 mo recall visit.

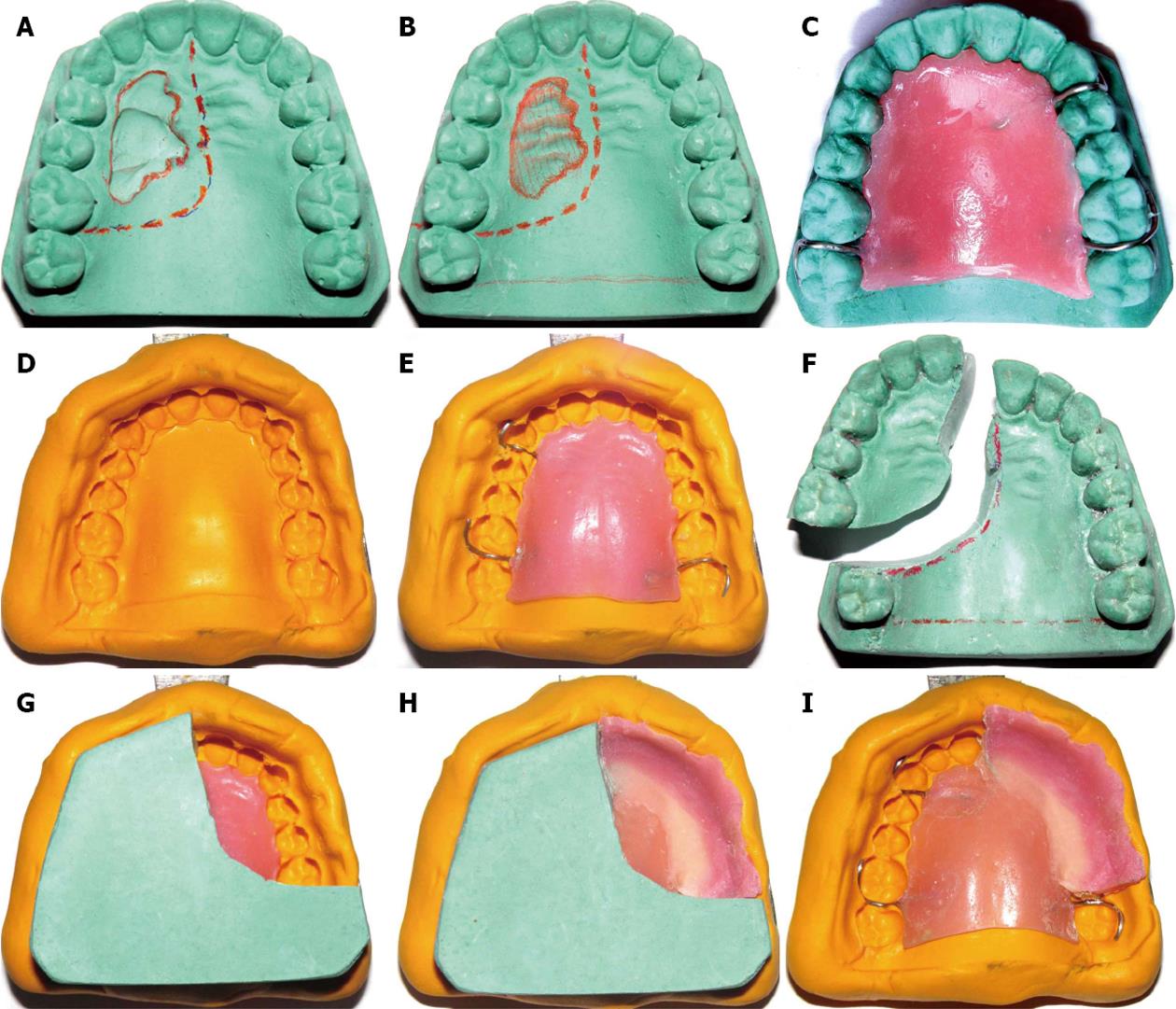

Prior to surgery maxillofacial prosthodontist should examine patient and discuss the plan of treatment with surgeons about a proposed line of incision and amount of resection (Figure 1A).

A pre-surgical impression of the maxillary arch is made with irreversible hydrocolloid and poured to obtain a working cast. An anticipated line of resection is drawn with a marking pencil on the cast following discussion with maxillofacial and plastic surgeons.

The area (of the legion) on the cast is modified to obtain normal anatomical contours (Figure 1B). For example, swollen areas of the lesion on the cast can be scraped-out and defect (ulcer/breach) areas can be built-up with dental stone in order to create the normal anatomical tissue form on the cast.

Labial/lingual infrabulge retentive areas of the remaining healthy teeth are engaged with the retentive clasp arms. A processed prosthetic base is fabricated in heat polymerizing acrylic resin by incorporating the clasps (Figure 1C).

The processed prosthetic base is reseated on the maxillary cast and an over-impression of the whole cast (along with the seated processed prosthetic base) is made with polyvinyl-siloxane putty in perforated stock metal tray to form putty impression index (PII) (Figure 1D). Facial surface on the defect side of the cast should be completely recorded in the over-impression till border areas.

The PII and the cast are separated from each other. The prosthetic base is reseated on the PII (Figure 1E).

The separated cast is sectioned according to the anticipated line of resection. The planned defect section of the cast is separated from the remaining normal portion (Figure 1F). This remaining portion (of normal structures) of the cast is used to fabricate the prosthesis.

The PII (along with the processed prosthetic base) is reseated onto the remaining portion of the cast (Figure 1G).

Prosthetic teeth are created with sprinkle-on technique by incrementally adding tooth-colored autopolymerizing acrylic resin into the impression areas of teeth in the PII. The facial flange can also be created by adding the pink colored autopolymerizing acrylic resin uniformly 2-3 mm in width (Figure 1H).

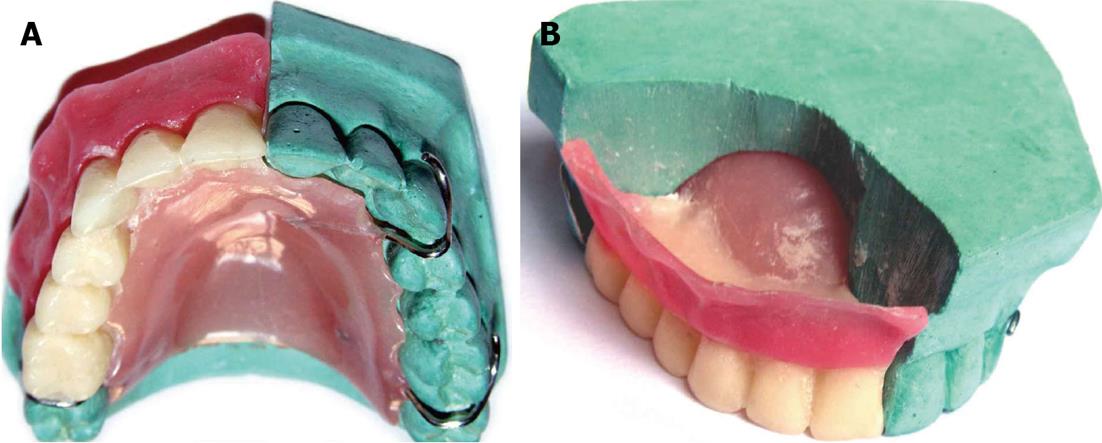

After setting the PII along with the prosthesis is separated from the cast (Figure 1I) and then PII is separated from the prosthesis carefully. The excess resin is removed and the flange and teeth areas are finished and polished in a conventional manner (Figure 2)[11,12] Note that the smooth borders and polished surfaces are critical parameters to avoid any tissue injury. Occlusal surfaces of the posterior teeth can be trimmed off by approximately 2 mm to make them out of occlusion[1,8].

The prosthesis must be disinfected before using it in the mouth with any suitable disinfectant like 2% glutaraldehyde solution.

Routine minor adjustments are carried out and the prosthesis can be seated in position immediately after surgery. A surgical pack can be placed in the defect area before placement of the obturator if necessary.

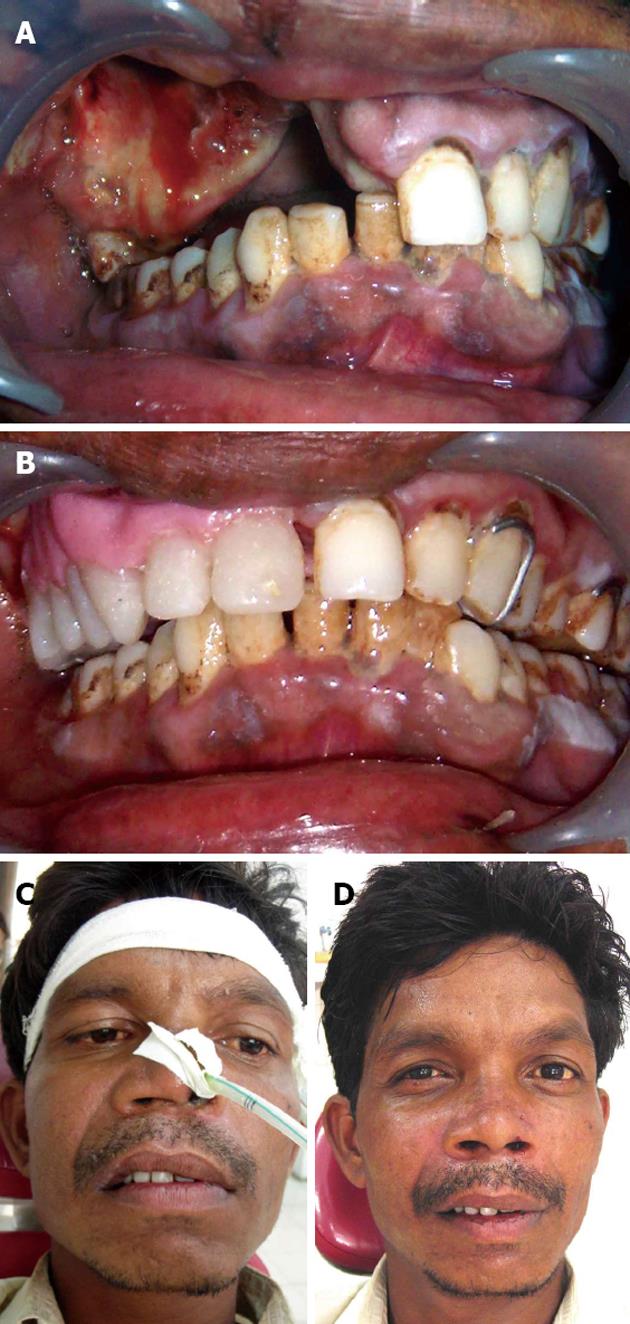

We have treated 11 patients undergone maxillary partial or subtotal resection with the immediate surgical obturator in last 2 years (Table 1). Out of 11 patients, 6 had Armany’s Class I defect, 4 had class II defect (Figure 3) and 1 had Class IV defect[13]. All 11 patients were assessed at the interval of 1, 2, 6 and 12 mo follow up visits for evaluation of healing process and evaluated for patients’ own satisfaction level and clinicians’ perception level for bilateral facial symmetry on VAS. Patients’ satisfaction level was recorded on VAS (with 0 indicating no satisfaction and 100 indicating complete satisfaction) and it ranges between 74% and 94% (with average of 87%) (Table 1). Four different prosthodontists have visually evaluated facial asymmetry of patients at 6 mo recall visit and indicated their visual perception for symmetry of the face on VAS (with 0 indicating completely asymmetric face and 100 indicating completely symmetric face). The average VAS scores of 4 clinicians’ readings were calculated and presented in Table 1. Clinician perception VAS scores vary between 71% and 93% (with average of 84%).

| Sr.No | Patient’s surgical defect-type (Armany Classification) | Age(yr) | Sex(M/F) | Diagnosis | Post-surgical radiotherapy (Y/N) | Patient’s satisfaction level (VAS at 6 mo) | Clinicians’ observation for facial asymmetry (Average VAS scores of 4 clinicians at 6 mo) |

| 1 | Class II | 47 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma of right maxilla | Y | 86% | 84% |

| 2 | Class I | 45 | M | Adenocarcinoma of left maxillary sinus | Y | 78% | 86% |

| 3 | Class II | 50 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma of maxillary sinus | Y | 92% | 80% |

| 4 | Class IV | 63 | M | Ameloblastoma of palate | N | 93% | 88% |

| 5 | Class I | 50 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma of right maxilla | Y | 88% | 74% |

| 6 | Class I | 65 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma of left maxilla | Y | 94% | 93% |

| 7 | Class I | 65 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma of right maxilla | Y | 83% | 71% |

| 8 | Class II | 40 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma of hard palate | Y | 94% | 93% |

| 9 | Class I | 36 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma of Maxillary sinus | Y | 81% | 86% |

| 10 | Class I | 35 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma of right maxilla | Y | 74% | 73% |

| 11 | Class II | 48 | M | Ameloblastoma of left maxilla | N | 94% | 92% |

Neglecting timely prosthodontic rehabilitation may lead to inappropriate facial contour which is difficult to correct[14-16]. The significance of immediate surgical obturators has been well documented. Immediate obturators resist tissue contracture of the soft tissues that are not supported by the underlying osseous structures. During healing phase, surgical wound is protected from external irritants, contaminants, food debris and trauma[17,18].

The borders of the defect are more prone to collapse due to lack of underlying support. Addition of teeth and labial/buccal flanges provide maximum support to the borders. Facial contours of the immediate obturator described in this article support overlying skin and skin grafts with optimum pressure providing their close adaptation to the cavity walls without getting contracted. After the operation, patients are able to swallow food more readily and to resume a normal diet at an earlier stage which leads to shorter recovery period[4]. Addition of teeth to the obturator allows mastication of semisolid food in initial phase and solid food several days later[4,14]. Speech is minimally altered and in many instances remains nearly unchanged[19,20]. Also the awareness of the surgical defect by the tongue is prevented and the patient remains unaware of the size of the defect giving the patient a positive psychological boost. By maintaining facial contour and aesthetics, patients are psychologically better equipped to face rehabilitation[21].

Immediate restoration of the resected tissues by means the obturator that restores every missing portion of the tissues helps patients undergo unnoticed to the surgery. This gives patient positive psychological boost during the initial vulnerable period of healing. According to many authors, the posterior teeth should not be added to surgical obturator as they may exert unnecessary stress on the open wound and delay the healing process[3]. This technique describes replacement of dentition that would be missing followed by grinding occlusal contacts of posterior teeth (at least 2 mm) to position them out of occlusion. The facial surfaces must be kept intact to serve the purpose of facial soft tissue support as well as esthetics without disturbing the healing process. Anterior teeth should not be altered unless the incisal contacts hinder the healing tissues. The purpose of adding missing teeth (anteriors or posteriors) may prevent significant psychological trauma to the patient and helps to prevent scar contracture and subsequent disfigurement. The developed facial flange also helps to support the facial soft tissues which can maintain the patient’s original facial esthetic appearance.

Contracture of the wound and scar formation leave very serious facial deformities after cancer surgeries[22]. Even slight depression in either side will also cause major deformity due to face value and patient’s vulnerability towards esthetic appearance. If the radiotherapy follows the surgery the tissues become even more friable and are difficult to manage due to loss of natural laxity. Maximum wound contracture happens in initial stages within 4-6 wk. This is the period in which the losses of intraoral structures also cause difficulty in mastication and deglutition. Thus in initial stages of healing, patients may undergo severe psychological depression due to multiple problems. Immediate obturation can create a positive effect on the patients' psychology.

Interim obturators with teeth may be made using several methods, using a celluloid matrix[2], modifying a surgical obturator[7], using a denture duplicator[23], or using light[11,24] or heat-polymerized acrylic resin[25]. The obturator fabricated with this technique utilizes the PII of patient’s original tissue form and duplicated mostly in heat and slightly in autopolymerizing acrylic resin.

Same surgical obturator can later (for 4-6 mo) serve as an interim obturator following modification of the tissue surfaces thus it saves time and cost.

The space automatically formed between intaglio surfaces of facial flange and palatal plate can easily be utilized for placement of the surgical pack immediately after the surgery. Thus the obturator can provide supporting and stabilizing medium for the surgical pack.

The same surgical obturator can be an effective tool for implant retained definitive fixed or removable prosthesis. Most of the acquired defects are surgically covered with thin mucosa which is not able to support denture bases. In such situations dental implants are indicated, leaving the vulnerable and/or non keratinized mucosa unloaded[26]. The use of dental implants is an alternative option to achieve better function and self confidence due to improved retention and stability[27]. Edentulous patients undergoing partial maxillectomy must be treated with implant supported ball and socket attachments to achieve retention to the surgical obturator. Same obturator can be used to prepare the diagnostic as well as surgical template for dental implant placement.

As the teeth and facial flanges of the obturator are created in auto polymerizing acrylic resin, the free residual monomer may irritate the supporting tissues and hamper the healing process. The light polymerizing acrylic resin can be used alternatively to solve this problem provided the combinations of the light polymerizing acrylic resins and the methylmethacrylate based denture base resins were selected carefully to ensure sufficient bond strength[11,23,24,28].

Future prospective clinical trials with large sample size should be promoted to treat cancer patients with better esthetics and function.

P- Reviewers: Haraszthy V, Nyan M S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Beumer J III, Curtis D, Firtell D. Restoration of acquired hard palate defects: etiology, disability and rehabilitation. Maxillofacial Rehabilitation: Prosthodontic and Surgical Considerations. St. Louis, MO: Medico Dental Media International 1996; 225-284. |

| 2. | Kouyoumdjian JH, Chalian VA. An interim obturator prosthesis with duplicated teeth and palate. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;52:560-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Patil PG. Modified technique to fabricate a hollow light-weight facial prosthesis for lateral midfacial defect: a clinical report. J Adv Prosthodont. 2010;2:65-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Patil PG, Patil SP. Nutrition and cancer. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:106-107; author reply 107. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Patil PG. The spring retained delayed surgical obturator for total maxillectomy: a technical note. Oral Surgery. 2010;3:8-10. |

| 6. | King GE, Martin JW. Cast circumferential and wire clasps for obturator retention. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;49:799-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Wolfaardt JF. Modifying a surgical obturator prosthesis into an interim obturator prosthesis. A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;62:619-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arcuri MR, Taylor TD. Clinical management of the dentate maxillectomy patient. Clinical maxillofacial prosthetics. Carol Stream (IL): Quintessence 2000; 103-120. |

| 9. | Patil PG. New technique to fabricate an immediate surgical obturator restoring the defect in original anatomical form. J Prosthodont. 2011;20:494-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Shambharkar VI, Puri SB, Patil PG. A simple technique to fabricate a surgical obturator restoring the defect in original anatomical form. J Adv Prosthodont. 2011;3:106-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gardner LK, Parr GR, Richardson DW. An interim buccal flange obturator. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shaker KT. A simplified technique for construction of an interim obturator for a bilateral total maxillectomy defect. Int J Prosthodont. 2000;13:166-168. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Aramany MA. Basic principles of obturator design for partially edentulous patients. Part I: classification. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;40:554-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Heggie AA, MacFarlane WI, Warneke SC. Immediate prosthetic replacement following major maxillary surgery. Aust N Z J Surg. 1980;50:370-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Park KT, Kwon HB. The evaluation of the use of a delayed surgical obturator in dentate maxillectomy patients by considering days elapsed prior to commencement of postoperative oral feeding. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;96:449-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lapointe HJ, Lampe HB, Taylor SM. Comparison of maxillectomy patients with immediate versus delayed obturator prosthesis placement. J Otolaryngol. 1996;25:308-312. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lang BR, Bruce RA. Presurgical maxillectomy prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent. 1967;17:613-619. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Huryn JM, Piro JD. The maxillary immediate surgical obturator prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;61:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arigbede AO, Dosumu OO, Shaba OP, Esan TA. Evaluation of speech in patients with partial surgically acquired defects: pre and post prosthetic obturation. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006;7:89-96. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Oki M, Iida T, Mukohyama H, Tomizuka K, Takato T, Taniguchi H. The vibratory characteristics of obturators with different bulb height and form designs. J Oral Rehabil. 2006;33:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Minsley GE, Warren DW, Hinton V. Physiologic responses to maxillary resection and subsequent obturation. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;57:338-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Türkaslan S, Baykul T, Aydın MA, Ozarslan MM. Influence of immediate and permanent obturators on facial contours: a case series. Cases J. 2009;2:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kaplan P. Stabilization of an interim obturator prosthesis using a denture duplicator. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:377-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | DaBreo EL. A light-cured interim obturator prosthesis. A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;63:371-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Arena CA, Evans DB, Hilton TJ. A comparison of bond strengths among chairside hard reline materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1993;70:126-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Esser E, Wagner W. Dental implants following radical oral cancer surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1997;12:552-557. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Cheng AC, Wee AG, Shiu-Yin C, Tat-Keung L. Prosthodontic management of limited oral access after ablative tumor surgery: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;84:269-273. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Fellman S. Visible light-cured denture base resin used in making dentures with conventional teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;62:356-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |