Published online May 20, 2013. doi: 10.5321/wjs.v2.i2.30

Revised: December 27, 2012

Accepted: January 5, 2013

Published online: May 20, 2013

Processing time: 200 Days and 10.3 Hours

AIM: To investigate the microleakage of two different root canal obturation systems, using the nuclear medicine approach.

METHODS: Twenty-six single-rooted extracted teeth were selected. The crowns were sectioned to obtain 15-mm long root segments and each tooth was prepared using rotary ProFile® instruments. The roots were divided into 2 experimental groups using RealSeal 1 and RealSeal sealer or Thermafil and TopSeal sealer as well as two control groups. On the 7th and the 28th day the apices were submersed in a solution of 99mTc-Pertechnetate during 3 h. The radioactivity was counted using a γ camera.

RESULTS: The present study showed that none of the root canal-filled teeth was leakage free. The statistical analyses were made using Kruskal-Wallis and statistical significance was assessed using α = 0.05. Although apical leakage measured in counts per minute (cpm) in the Thermafil/TopSeal group was lower than in the RealSeal/RealSeal group (363 916 ± 180 707.7 cpm vs 533 427 ± 414 020.6 cpm) on 7th day and (1 678 200 ± 567 217.4 cpm vs 2 240 518 ± 383 356.7 cpm) on 28th day, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05). In the Thermafil/TopSeal group and RealSeal 1/RealSeal group it was found that over time, the number of counts increased between 7 d and 28 d (363 916 ± 180 707.7 cpm vs 1 678 200 ± 567 217.4 cpm) and (533 427 ± 414 020.6 cpm vs 2 240 518 ± 383 356.7 cpm), respectively, with statistically significant differences (Thermafil/TopSeal group, P = 0.015 and RealSeal 1/RealSeal group, P = 0.036).

CONCLUSION: Both carrier-based Realseal 1 and Thermafil techniques showed a similar sealing effect, but none of the materials was leakage free.

- Citation: Ferreira MM, Abrantes M, Carrilho EV, Botelho MF. Quantitative scintigraphic analysis of the apical seal in Thermafil/Topseal and RealSeal 1/Realseal filled root canals. World J Stomatol 2013; 2(2): 30-34

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6263/full/v2/i2/30.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5321/wjs.v2.i2.30

It has been established that apical periodontitis is caused by bacteria derived from the root canal[1,2]. The first stage of root canal therapy is microbial control, followed by root canal filling. Microbial control includes removal of the protein degradation products, toxins, and mainly bacteria[3]. The root canal filling must seal the canal space both apically and coronally and the most commonly used material for root canal obturation is gutta-percha combined with a sealer. Gutta-percha is considered an impermeable core material but does not bond to root dentin walls.

Recent studies have shown that the obturation system with Resilon is able to create a monoblock which prevents bacterial leakages in vitro and in vivo[4,5]. In addition, it also increases the fracture resistance of the filled roots[4,6].

Methacrylate resin-based sealers are used in endodontics for improving bonding to radicular dentin. They are based on dentin adhesion techniques derived from restorative dentistry[7]. However, effective bonding within a deep and narrow canal is a challenge, mainly because of the unfavorable geometry of the root canal system to relief of polymerization shrinkage stresses[8,9].

Chemical irrigants are essential for successful debridement of root canals, during shaping and cleaning procedures which aim to expose the collagen networks. It has been shown that the removal of the organic phase from the mineralized dentine by NaOCl enhances dentin permeability to ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Additionally, removal of the smear layer has been recommended in order to reduce microleakage and improve the fluid-tight seal of filled canals[10-12]. For this purpose, EDTA has been commonly used and is recommended by manufacturers as the final irrigant before the application of methacrylate resin-based sealers[13,14].

To date, several studies have evaluated the outcomes of different root canal sealers with various leakage models[15-18]. The major problem of most laboratory-based leakage testing models is that the obtained data are qualitative rather than quantitative, raising doubts about their reliability[15-17,19].

The use of sodium pertechnetate (99mTcNaO4) in nuclear medicine is well established and the evolution of diagnostic conventional nuclear medicine can be mainly attributed to the existence and the chemical versatility of this radionuclide[20,21].

The most relevant property of 99mTc is its 140 keV γ photon emission with 89% abundance, which is optimum for imaging with the γ cameras used in nuclear medicine. Moreover, its half-life of 6 h is enough to prepar-e the radiopharmaceuticals, to perform their quality control, and to administer them to the patient for imaging studies, while having a favorable dosimetry. The rapid growth in this field in the last few decades is attributable, in addition to its ideal radionuclide characteristics, to the design and development of 99Mo/99mTc generators and lyophilized kits to facilitate the formulation of 99mTc compounds in hospital radiopharmacies. 99mTcNaO4 is obtained in the form of sodium pertechnetate directly from the generator after elution with saline. Given all the 99mTc characteristics and considering that nuclear medicine is an approach with high sensitivity and specificity, radionuclides may provide quantitative and objective results concerning infiltration.

Thus, the aim of this study was to use nuclear medicine methodologies to assess microleakage of root canals. For that purpose we compared the sealing ability of roots filled with Realseal 1/Realseal, with those that were filled with gutta-percha and an epoxy-based root canal sealer (Thermafil/Topseal) using the 99mTcNaO4.

Twenty-six extracted human premolar teeth, with a single root and the apex completely formed were used in this study. These teeth were stored until use in a 0.9% sodium chloride solution containing 0.02% sodium azide at 4 °C, to prevent bacterial growth.

The crowns were sectioned with a high-speed bur and water spray, in order for all the roots to be approximately 15 mm long. Canal length was determined by inserting a K file, ISO size #15 (Dentsply Maillefer, CH-1338 Ballaigues, Switzerland) into the canal until its tip was visible at the apical foramen. The working length was established 1 mm short of the apex.

Instrumentation of the root canals was performed with a crown-down technique using ProFile nickel-titanium rotary instruments (Dentsply Maillefer, CH-1338 Ballaigues, Switzerland). The handpiece was used with an electric motor (X-Smart; Dentsply Maillefer, CH-1338 Ballaigues, Switzerland) at 250 rpm. Instrumentation was completed with 35.04 ProFile instruments up to the working length. After the use of each instrument, the canals were irrigated with 3 mL of 2.5% NaOCl by using a 27-gauge Monoject irrigation needle (Sherwood Medical, St. Louis, MO). The final rinse was performed using 3 mL of 17% EDTA for 3 min, and 3 mL of 2.5% NaOCl for 3 min (Pulpdent Corporation, Watertown, MA) followed by 3 mL of saline solution for 1 min. The canals were dried with size 35 absorbent paper points (Dentsply Maillefer, CH-1338 Ballaigues, Switzerland). Finally, the roots were randomly divided into 2 experimental groups of 10 teeth each (group 1 and 2) and two control groups of 6 teeth. In group 1 the obturations were performed with TopSeal sealer (Dentsply Maillefer, CH-1338 Ballaigues, Switzerland) placed into the canal using a 35.04 master points. Then, the Thermafil (Dentsply Maillefer, CH-1338 Ballaigues, Switzerland) carrier points 35.04, was inserted in the canal after being thermo plasticized in the ThermaPrep oven (Dentsply Maillefer, CH-1338 Ballaigues, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The excess of gutta-percha was removed with a hot instrument, and then the root canal orifices were sealed using a flowable resin composite (Vertise Flow, Kerr SA, 6934 Bioggio, Switzerland).

As for group 2, the obturations were performed by using 35.04 RealSeal 1 carrier points. The RealSeal primer was placed into the root canal with a microbrush, and the excess of primer was removed with paper points. Then, the RealSeal SE sealer was placed into the canal with a #35 K-file. The RealSeal 1, 35.04, was inserted in the canal after being thermo plasticized in the Realseal 1 oven (SybronEndo). After canal filling, the coronal surface of the root filling was light cured for 40 s (Optilux; Sybron Kerr, Danbury, CT), the excess of obturation material was removed with a round bur and the root canal orifices were sealed using a flowable resin composite (Vertise Flow, Kerr SA, 6934 Bioggio, Switzerland).

All experimental procedures were carried out by the same endodontist.

After the filling procedures, two radiographs were taken in orthoradial and proximal views, to analyse the quality of the canal filling.

The filled root segments were stored for 1 wk at 37 °C and 100% relative humidity to allow the sealers to set completely, before leakage evaluation using a nuclear medicine approach.

For the control group (n = 6), procedures for selection and instrumentation were the same as those described for the experimental groups, except that the prepared root canal space was not obturated in the positive control group.

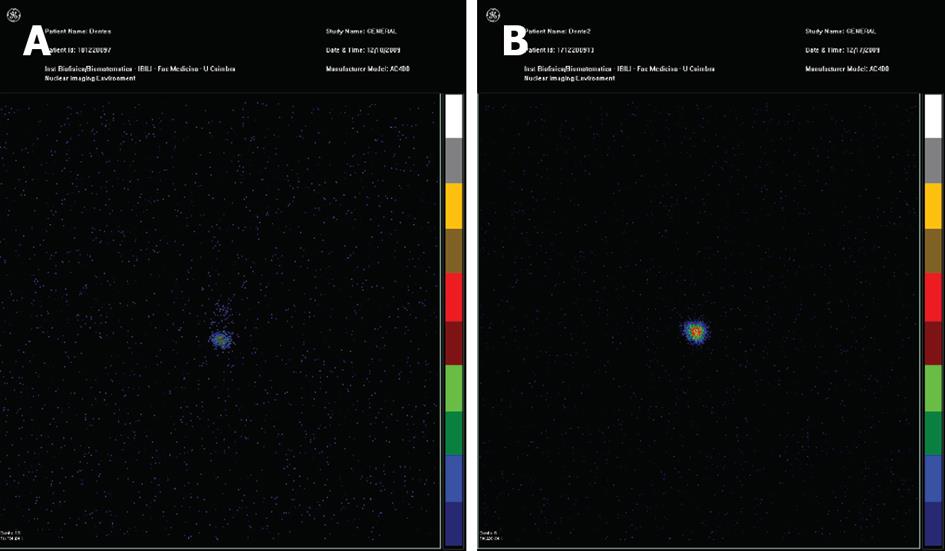

For leakage determination, the roots of the experimental groups and positive control group were covered by two layers of nail varnish, except for 2 mm of the apical foramen. In the negative control group, the entire root surface, including the apical foramen was covered by the nail varnish. The teeth were suspended in Eppendorf tubes, containing 99mTcNaO4 remaining in contact with the solution for 3 h. After this period the roots were dried on absorbent paper and the varnish was then removed. Scintigraphic images were made for each tooth using a γ camera (GE 400 AC, Milwaukee, United States). For each tooth a static image was acquired for 3 min at a 512 × 512 matrix size (Figure 1). Regions of interest (ROIs) in each image were drawn over each tooth, to obtain the total counts and the counts per minute (cpm). All the nuclear medicine procedures were performed by a single nuclear medicine specialist, in a blinded fashion. The procedure was repeated at 7 and 28 d.

The statistical analyses were cariied out using the Kruskal-Wallis method and statistical significance was assessed using α = 0.05, using statistics software (SPSS version 19, Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

The means and standard deviations of ROI cpm from the specimens at 7 and 28 d after obturation are given in Table 1. In group 1 (Thermafil/TopSeal, Figure 1A), it was found that over time, the number of counts increased between 7 and 28 d: 363 916 and 1 678 200 cpm, respectively. These differences are statistically significant (P = 0.015, Table 1). In group 2 (RealSeal1/RealSeal, Figure 1B) statistically significant differences were found between the counts obtained at 7 and 28 d: 533 427 and 2 240 518 cpm, respectively (P = 0.036, Table 1). Comparing the core/sealers, it was found that although the Thermafil system had less leakage than RealSeal 1, there was no statistically significant difference.

Analysis of the sealing ability of new root canal obturation systems is important, in relation to both the coronal and apical leakage, because they have been cited as a significant cause of post treatment disease[10,11].

Although a bacterial leakage model may appear to be more clinically relevant than a fluid infiltration model, the latter technique was used here[22].

Dye penetration is one of the most commonly used methods for the investigation of apical leakage because of the simplicity of both the laboratory procedures and the final reading of the results.

Although the fluid transport model/bacterial penetration has been widely used to determine leakage around coronal restorations and endodontic retrograde fillings[23] and has been proven to be more sensitive than conventional dye penetration, radionuclide methods are not usually used.

The principal advantage of using a radioactive probe with 99mTcNaO4 is that this radionuclide method is quantitative and nondestructive, enabling measurement of microleakage from the same specimens at intervals over extended periods, without destroyed the sample. This procedure is important for the study of interfaces. With other methods, artifacts may occur at the surface level due to the section cutting process, but this does not occur with radionuclides and it is possible to evaluate leakage over extended periods.

Thermafil is a simple obturation method with short execution time, and which, according to the manufacturers, confers a good seal. According to Inan et al[24], obturation with systems carriers has a smaller variation in the values of leakage than vertical and lateral condensation, perhaps a good indicator for the best method for use in the clinic.

Because an properly filled canal requires an appropriate cleaning and shaping procedure, a 35.04 rotary file was used at 1 mm from the foramen. Better clinical antimicrobial efficacy using this diameter has been reported in the mandibular molar, than with a 30.04 diameter file when sodium hypochlorite was used[25].

Self-etch sealers, such as MetaSeal (Parkell, Farmington, NY) and RealSeal SE, have been incorporated recently into endodontic practice. This kind of sealer has been designed with the intention of combining a self-etching primer and a moderately filled flowable composite into a single product, to make possible adhesion to dentin substrates. These sealers are similar to self-adhesive luting cements, and it is assumed that the bonding mechanism is similar[26].

Furthermore, future studies using microscopic techniques should be performed to show if the Resilon or gutta-percha interfaces are able to avoid bacterial penetration, because few studies currently exist that verify in situ the presence of bacteria in samples showing leakage.

The findings of this study demonstrated that on the seventh day, specimens filled with RealSeal 1/RealSeal leaked more than specimens filled using Thermafil and TopSeal.

Similarly, RealSeal 1/RealSeal showed increased leakage at all times, irrespective of the obturation technique with Thermafil/TopSeal. Although adhesive products hold promise for the future, a number of technical hurdles need to be overcome in order to maximize the potential benefits of adhesive root canal fillings. One challenging concern is the very limited capacity of long narrow root canals to relieve polymerization shrinkage stresses created by methacrylate-based sealers via resin flow[27]. This may be expressed in terms of the cavity configuration factor or C-factor, being the ratio of the bonded surface area in a cavity to the unbonded surface area[28].

Under the experimental conditions of the current ex vivo experiment, the results demonstrated that the newly developed RealSeal 1/RealSeal core material combination of root canal filling materials does not improve the microleakage resistance compared with Thermafil/Topseal filling. Nevertheless, further investigation of other features of root canal sealers is required.

The sealing ability of root canal obturation systems is important, in both the coronal and apical leakage. Gutta-percha is considered an impermeable core material but does not bond to root dentin walls. Recently, a resin-based obturation system, Real Seal was introduced as an alternative to gutta-percha. It consists of a resin material, named Resilon. Many studies have reported that the obturation system with Resilon and Methacrylate resin-based sealers is able to prevents bacterial leakages in vitro and, in addition, increases the fracture resistance of the filled roots.

Thermafil is a simple obturation method with short execution time, and which, according to the manufacturers, confers a good seal. Self-etch sealers, such as MetaSeal (Parkell, Farmington, NY) and RealSeal SE, have been incorporated recently into endodontic practice. This kind of sealer has been designed with the intention of combining a self-etching primer and a moderately filled flowable composite into a single product, to make possible adhesion to dentin substrates, thereby preventing microleakage.

Obturation with systems carriers has a smaller variation in the level leakage than with vertical and lateral condensation, perhaps a good indicator of the best method for use in the clinic. Previous findings have evaluated the outcomes of different root canal sealers with various leakage models. The major problem of most laboratory-based leakage testing models is that the obtained data are qualitative rather than quantitative, raising doubts about their reliability. The principal advantages of using a radioactive probe with 99mTcNaO4 is that this method is a quantitative and nondestructive method, enabling measurement of microleakage from the same specimens at intervals over extended periods, without destroying the sample.

The study results suggest that the RealSeal 1/RealSeal core material combination could potentially be used for root canal filling.

This is an interesting study, and is well written for publication.

P- Reviewer El-Askary F S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Colonnello F, Signorini C. [Nosologic arrangement of acute dyspneic infectious respiratory diseases and their treatment]. G Mal Infett Parassit. 1965;17:723-744. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:340-349. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Möller AJ, Fabricius L, Dahlén G, Ohman AE, Heyden G. Influence on periapical tissues of indigenous oral bacteria and necrotic pulp tissue in monkeys. Scand J Dent Res. 1981;89:475-484. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Shipper G, Ørstavik D, Teixeira FB, Trope M. An evaluation of microbial leakage in roots filled with a thermoplastic synthetic polymer-based root canal filling material (Resilon). J Endod. 2004;30:342-347. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Shipper G, Teixeira FB, Arnold RR, Trope M. Periapical inflammation after coronal microbial inoculation of dog roots filled with gutta-percha or resilon. J Endod. 2005;31:91-96. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Teixeira FB, Teixeira EC, Thompson JY, Trope M. Fracture resistance of roots endodontically treated with a new resin filling material. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:646-652. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Belli S, Ozcan E, Derinbay O, Eldeniz AU. A comparative evaluation of sealing ability of a new, self-etching, dual-curable sealer: hybrid root SEAL (MetaSEAL). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e45-e52. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Carvalho RM, Pereira JC, Yoshiyama M, Pashley DH. A review of polymerization contraction: the influence of stress development versus stress relief. Oper Dent. 1996;21:17-24. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Tay FR, Loushine RJ, Lambrechts P, Weller RN, Pashley DH. Geometric factors affecting dentin bonding in root canals: a theoretical modeling approach. J Endod. 2005;31:584-589. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Clark-Holke D, Drake D, Walton R, Rivera E, Guthmiller JM. Bacterial penetration through canals of endodontically treated teeth in the presence or absence of the smear layer. J Dent. 2003;31:275-281. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Economides N, Kokorikos I, Kolokouris I, Panagiotis B, Gogos C. Comparative study of apical sealing ability of a new resin-based root canal sealer. J Endod. 2004;30:403-405. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Shahravan A, Haghdoost AA, Adl A, Rahimi H, Shadifar F. Effect of smear layer on sealing ability of canal obturation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod. 2007;33:96-105. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Khedmat S, Shokouhinejad N. Comparison of the efficacy of three chelating agents in smear layer removal. J Endod. 2008;34:599-602. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Carvalho AS, Camargo CH, Valera MC, Camargo SE, Mancini MN. Smear layer removal by auxiliary chemical substances in biomechanical preparation: a scanning electron microscope study. J Endod. 2008;34:1396-1400. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Camps J, Pashley D. Reliability of the dye penetration studies. J Endod. 2003;29:592-594. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Delivanis PD, Chapman KA. Comparison and reliability of techniques for measuring leakage and marginal penetration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53:410-416. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Barthel CR, Moshonov J, Shuping G, Orstavik D. Bacterial leakage versus dye leakage in obturated root canals. Int Endod J. 1999;32:370-375. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kim YK, Grandini S, Ames JM, Gu LS, Kim SK, Pashley DH, Gutmann JL, Tay FR. Critical review on methacrylate resin-based root canal sealers. J Endod. 2010;36:383-399. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Goldman M, Simmonds S, Rush R. The usefulness of dye-penetration studies reexamined. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:327-332. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Pogrel MA, Kopf J, Dodson TB, Hattner R, Kaban LB. A comparison of single-photon emission computed tomography and planar imaging for quantitative skeletal scintigraphy of the mandibular condyle. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Banerjee S, Pillai MR, Ramamoorthy N. Evolution of Tc-99m in diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals. Semin Nucl Med. 2001;31:260-277. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Michaïlesco PM, Valcarcel J, Grieve AR, Levallois B, Lerner D. Bacterial leakage in endodontics: an improved method for quantification. J Endod. 1996;22:535-539. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Wu MK, De Gee AJ, Wesselink PR, Moorer WR. Fluid transport and bacterial penetration along root canal fillings. Int Endod J. 1993;26:203-208. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Inan U, Aydemir H, Taşdemir T. Leakage evaluation of three different root canal obturation techniques using electrochemical evaluation and dye penetration evaluation methods. Aust Endod J. 2007;33:18-22. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Shuping GB, Orstavik D, Sigurdsson A, Trope M. Reduction of intracanal bacteria using nickel-titanium rotary instrumentation and various medications. J Endod. 2000;26:751-755. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Resende LM, Rached-Junior FJ, Versiani MA, Souza-Gabriel AE, Miranda CE, Silva-Sousa YT, Sousa Neto MD. A comparative study of physicochemical properties of AH Plus, Epiphany, and Epiphany SE root canal sealers. Int Endod J. 2009;42:785-793. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Alster D, Feilzer AJ, de Gee AJ, Davidson CL. Polymerization contraction stress in thin resin composite layers as a function of layer thickness. Dent Mater. 1997;13:146-150. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Feilzer AJ, De Gee AJ, Davidson CL. Setting stress in composite resin in relation to configuration of the restoration. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1636-1639. [PubMed] |