Published online Jul 28, 2015. doi: 10.5320/wjr.v5.i2.135

Peer-review started: October 3, 2014

First decision: November 4, 2014

Revised: January 27, 2015

Accepted: March 18, 2015

Article in press: March 20, 2015

Published online: July 28, 2015

Processing time: 305 Days and 18.8 Hours

In this review, we report on the use of indwelling pleural catheters in the treatment of malignant pleural effusions. We describe the most commonly used catheter. Also, treatment with indwelling pleural catheters as compared to talc pleurodesis is reviewed. A comparison of efficacy, costs, effects on quality of life, and complications is made. Only one randomized controlled trial comparing the two is available up to date, but several are underway. We conclude that treatment for malignant pleural effusions with indwelling pleural catheters is a save, cost-effective, and patient-friendly method, with low complication rates.

Core tip: Indwelling pleural catheters appear to be as efficient and cost-effective as talc pleurodesis in the treatment of malignant pleural effusions with a low complications rate. A great advantage is that terminally ill patients can be treated at home in the last stage of their lives.

- Citation: De Heer M, Cornelissen R, Hoogsteden HC, van den Toorn LM. Management of recurrent malignant pleural effusions with a tunneled indwelling pleural catheter. World J Respirol 2015; 5(2): 135-139

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6255/full/v5/i2/135.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5320/wjr.v5.i2.135

Indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs) are used worldwide, mostly in oncology centers, for the management of recurrent malignant and also non-malignant pleural effusions (MPE). Since their development approximately 15 years ago, increasing knowledge and expertise has developed. They offer the potential of increasing quality of life in terminally ill patients, and reducing length and number of hospital stays. A great advantage is that patients, who are terminally ill, can remain at home and be treated there in the last phase of their lives. This review aims to give an overview of the indications, complications and costs of indwelling pleural catheters. The alternative, i.e., chest tube drainage with pleurodesis, will also be discussed.

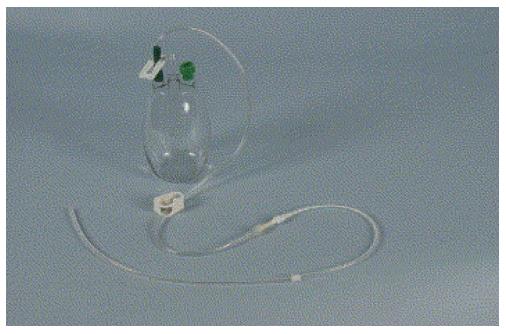

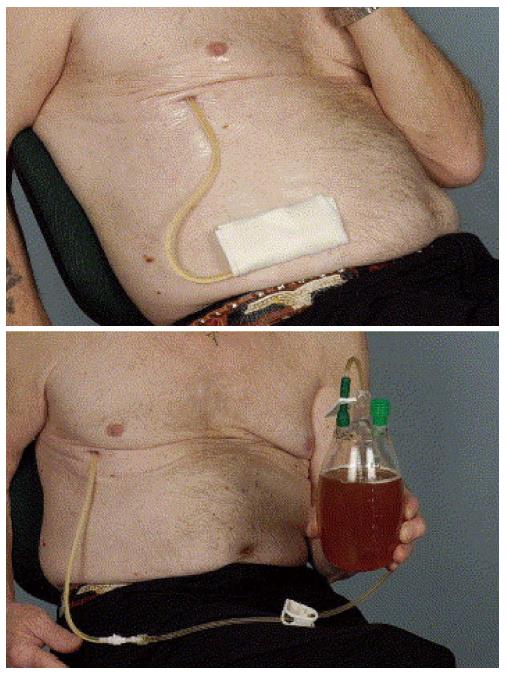

The most commonly used catheter for permanent drainage of pleural effusions is a flexible fenestrated silicone catheter with a cuff and a valve (Figure 1). The fenestrated portion of the catheter is inserted into the pleural space utilizing a peel away introducer (Seldinger technique). The portion of the catheter containing the cuff is tunneled subcutaneously, where it becomes fixed, thereby reducing the risk of dislocation. Also, because the catheter is tunneled, risk of infection is low. The remaining portion is left external to the body (Figure 2). Drainage occurs by connecting disposable vacuum bottles to the catheter. At the end is a one-way valve that can be attached to the vacuum drainage bottles. The most commonly used catheter is the 15.5 Fr PleurX catheter. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for the use in malignant pleural effusions[1] and 4 years later the license was extended to include all recurrent pleural effusions[2].

Before the availability of indwelling pleural catheters, symptom relieve was mostly achieved through repetitive drainage of pleural fluid, which resulted in frequent hospital visits. In some cases, partial pleurectomy was performed. However, only a small number of selected patients is eligible for such an invasive procedure, and it can be complicated by significant morbidity, especially before the era of video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS)[3,4]. In a randomized controlled trial, Rintoul et al[5] recently compared video-assisted thoracoscopic partial pleurectomy to talc pleurodesis in patients with malignant mesothelioma. They showed that partial pleurectomy did not improve overall survival, and was associated with significantly more complications, longer hospital stay and more costs compared to talc pleurodesis in these patients. It is therefore not recommended as a standard alternative for pleurodesis or IPC[5,6].

The guideline of the British Thoracic Society states that in patients with malignant pleural effusions with a life expectancy of > 1 mo, drainage should be performed with subsequent pleurodesis, whereby talc is the most effective sclerosant[6]. It also states that the use of IPCs is an effective alternative method in selected cases. Although talc pleurodesis can have relevant success rates, it is not without complications and is not an option for patients with a trapped lung, which is often the case in malignant pleural effusion[7]. Complications include tachycardia, dyspnea, fever, pain and in rare instance ARDS[8]. Also for patients with malignant pleural effusions, who generally have a short life expectancy and mostly are in poor condition, it is highly favorable to reduce the emotional and physical burden of repetitive hospital visits or the length of hospital stay. In a retrospective study, Putnam et al[9] demonstrated that patients treated with IPC had shorter hospital stay, and lower early mean charges as compared to those with chest tube drainage followed by pleurodesis. In another retrospective study of a large number of patients, who all underwent IPC insertion, it was shown that IPC resulted in good symptom control and shorter hospital stay. Also, a low complication rate was noted, the most severe being empyema in 3.2% of cases[10]. Moreover, the literature shows that spontaneous pleurodesis occurs in up to 51% of IPC cases, allowing removal of the catheter[10,11].

In the only randomized controlled trial comparing IPC to chest tube and talc pleurodesis, the TIME2 trial, no significant difference in dyspnea was noted in the first 42 d after insertion between the two groups (primary endpoint)[11]. Only after the 6 mo-point a clinically and statistically significant decrease in dyspnea in favor of the IPC group was seen. A decrease in chest pain was observed in both groups, but no significant difference was noted. There was a statistically significant difference in days in hospital for drainage or drainage-related complications over 12 mo in favor of the IPC group[11]. Significantly more adverse events, albeit non-serious, were noted in the IPC group; most of these were cellulitis around the site of insertion and catheter blockage.

A Dutch multicenter randomized controlled trial was designed comparing indwelling pleural catheters to talc pleurodesis in 120 patients with malignant pleural effusions (NVALT 14). The primary objective of the study is to compare the patient reported outcome of talc pleurodesis and indwelling pleural catheter, assessed by the Modified Borg dyspnea Score. Secondary objectives include the number of interventions and visits for MPE, adverse events, costs, overall survival, quality of life, and treatment outcome at 1, 3 and 6 mo. The inclusion phase has now successfully been concluded[11]. Other studies investigating indwelling pleural catheters are also ongoing at the moment[12-14].

In a study published almost 10 years ago, describing our own experience with IPC, we showed that in 70%-80% of patients, catheter use was uncomplicated and provided significant symptom relief. Infection was only seen in two (12%) patients, dislocation of the catheter in three (18%). In the final analysis, catheter use was unsatisfactory in two patients (12%)[15]. More recent experience with indwelling pleural catheters in our Lung Oncology Center is still very positive, as even more expertise has been acquired over the years.

Early complications directly associated with IPC insertion are rare. Some degree of pain in the first days following insertion is normal and can be treated by oral analgesics. Also, bruising in the subcutaneous catheter tract almost always occurs; potentially life-threatening bleeding is very rare. Oral anticoagulants can be restarted immediately after insertion[16].

Several studies have focused on the long-term complications of IPC. Thomas et al[17] retrospectively studied the incidence of catheter tract metastasis associated with IPC. In 10% of patients, catheter tract metastasis developed. Eighty-two percent of these patients had mesothelioma and all had prior pleural interventions before IPC insertion. The only significant variable associated with higher risk for catheter tract metastasis was a longer interval post-IPC insertion[17].

Another potential complication is pleural infection. In a multicenter retrospective study of 1021 patients, Fysh et al[18] reported an incidence of pleural infection of only 4.9%. The majority (94%) was successfully treated with antibiotics and in 54% of patients the IPC did not have to be removed. The most frequent causative agent of the infections was Staphylococcus aureus[18]. Other studies have shown similar results[19]. Patients undergoing chemotherapy with an IPC in place do not develop more infections than those with IPC not receiving chemotherapy[20]. Therefore chemotherapy does not have to be a contraindication for IPC placement.

A major question of course is whether IPC insertion improves quality of life. In a multicenter observational study of 51 patients, quality of life was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 en EORTC QLQ-LC13. A significant improvement of symptoms scale was seen[21]. Changes in the mean scores between baseline and 30 d, as assessed with the EORTC QLQ-C30, for global, functional, and symptoms scales were: + 9.21, + 6.93, and -9.59, respectively.

In the TIME2 trial, global quality of life as measured by the QLQ-30 was measured[11]. Quality of life was improved in both the IPC and the chest tube drainage with talc pleurodesis group.

IPC insertion usually can be done as an outpatient procedure. Therefore, little or no costs are made for hospital stay. However, IPCs cost about 700 Euros compared to 30 Euros for a simple Pleura Cath. Also, IPC treatment is associated with the use of many disposables, especially relatively expensive vacuum bottles. Also, in some cases home care is needed to help the patient with drainage. These factors push the total cost of IPC treatment. Several studies have investigated the cost of IPC treatment, often compared to test tube drainage and pleurodesis. Universal comparison remains a difficult task, because of different insurance systems and hospital management in different countries.

Boshuizen et al[22] looked at the direct costs of IPC treatment in one Dutch hospital; they concluded that the costs of IPC treatment are reasonable as compared to direct costs of hospitalization for pleurodesis. In a randomized controlled trial comparing IPC to talc pleurodesis, no difference in overall comparative costs was noted. Higher initial hospital bed costs were seen in the talc pleurodesis group, whereas in the IPC group most of the costs were made for ongoing drainage[23]. In patients with limited survival (< 14 wk), IPC was less costly with mean cost difference of -1719 US Dollars. In another study, this effect was seen in patients surviving less than 6 wk[24]. However, this financial benefit disappeared when substantial home care was needed for IPC treatment[23]. Taking these results together with the results of the earlier referred to TIME2 trial[11], the authors conclude that the use of either IPC or talc pleurodesis should be based on patients’ preferences after discussion of risks and benefits of each therapy[23].

Nowadays, IPC are used more frequently in the management of recurrent malignant pleural effusions and increasing expertise has been developed. Many studies show that IPC treatment has similar positive effects on dyspnea and quality of life as (repeated) chest tube drainage with talc pleurodesis. Effects on quality of life of a single intervention in this group of terminally ill patients with poor performance score have shown to be limited because of the many factors that influence these patients’ well being in the last stage of their life.

IPC treatment is generally well tolerated with hardly any serious complications reported. Also, the costs of IPC treatment are comparable to those of chest tube drainage with talc pleurodesis. In patients with limited survival, IPC treatment even appears less costly. However, as far as we know, only one randomized controlled trial investigating the difference between IPC treatment and talc pleurodesis is available up to date, but several are underway. More research should be performed to investigate which groups of patients will benefit most from IPC treatment. However, we can conclude that the use of IPC is a safe, cost-effective and equally effective intervention to treat recurrent malignant pleural effusion as compared with pleural drainage followed by talc pleurodesis.

P- Reviewer: Hida T, Porfyridis I S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Denver PleurX Pleural Catheter Kit, Denver PleurX Home Drainage Kit. Rockville: Food and Drug Administration 1997; . |

| 2. | PleurX Pleural Catheter and Drainage Kits. Rockville: Food and Drug Administration 2001; . |

| 3. | Harvey JC, Erdman CB, Beattie EJ. Early experience with videothoracoscopic hydrodissection pleurectomy in the treatment of malignant pleural effusion. J Surg Oncol. 1995;59:243-245. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Meuris K, Hertoghs M, Lauwers P, Hendriks JM, Van Schil PE. Subtotal pleurectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery for metastatic pleuritis. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;2012:mms008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rintoul RC, Ritchie AJ, Edwards JG, Waller DA, Coonar AS, Bennett M, Lovato E, Hughes V, Fox-Rushby JA, Sharples LD. Efficacy and cost of video-assisted thoracoscopic partial pleurectomy versus talc pleurodesis in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MesoVATS): an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1118-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65 Suppl 2:ii32-ii40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shaw P, Agarwal R. Pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD002916. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Brant A, Eaton T. Serious complications with talc slurry pleurodesis. Respirology. 2001;6:181-185. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Putnam JB, Walsh GL, Swisher SG, Roth JA, Suell DM, Vaporciyan AA, Smythe WR, Merriman KW, DeFord LL. Outpatient management of malignant pleural effusion by a chronic indwelling pleural catheter. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:369-375. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Tremblay A, Michaud G. Single-center experience with 250 tunnelled pleural catheter insertions for malignant pleural effusion. Chest. 2006;129:362-368. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, Wrightson JM, Stanton AE, Guhan A, Davies CW, Grayez J, Harrison R, Prasad A. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:2383-2389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | A randomized trial comparing longstanding indwelling pleural catheters with pleurodesis as a frontline treatment for malignant pleural effusion. iknlzuid.nl/trials. Trial number: AvL M10IPC/KWF 2010-4791/NVALT 14; . |

| 13. | Singapore National University Hospital. A Multicentre Randomised Study Comparing Indwelling Pleural Catheter With Talc Pleurodesis in Patients With a Malignant Pleural Effusion. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02045121 NLM Identifier: NCT02045121. |

| 14. | M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Effectiveness of Daily Versus Three Times a Week Drainage After Placement of Intrapleural Catheters for the Palliative Management of Pleural Effusions Associated With Malignancies. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00761618 NLM Identifier: NCT00761618. |

| 15. | van den Toorn LM, Schaap E, Surmont VF, Pouw EM, van der Rijt KC, van Klaveren RJ. Management of recurrent malignant pleural effusions with a chronic indwelling pleural catheter. Lung Cancer. 2005;50:123-127. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Bhatnagar R, Maskell NA. Indwelling pleural catheters. Respiration. 2014;88:74-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Thomas R, Budgeon CA, Kuok YJ, Read C, Fysh ET, Bydder S, Lee YC. Catheter tract metastasis associated with indwelling pleural catheters. Chest. 2014;146:557-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fysh ET, Tremblay A, Feller-Kopman D, Mishra EK, Slade M, Garske L, Clive AO, Lamb C, Boshuizen R, Ng BJ. Clinical outcomes of indwelling pleural catheter-related pleural infections: an international multicenter study. Chest. 2013;144:1597-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Van Meter ME, McKee KY, Kohlwes RJ. Efficacy and safety of tunneled pleural catheters in adults with malignant pleural effusions: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:70-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mekhaiel E, Kashyap R, Mullon JJ, Maldonado F. Infections associated with tunnelled indwelling pleural catheters in patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2013;20:299-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lorenzo MJ, Modesto M, Pérez J, Bollo E, Cordovilla R, Muñoz M, Pérez-Fidalgo JA, Cases E. Quality-of-Life assessment in malignant pleural effusion treated with indwelling pleural catheter: a prospective study. Palliat Med. 2014;28:326-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Boshuizen RC, Onderwater S, Burgers SJ, van den Heuvel MM. The use of indwelling pleural catheters for the management of malignant pleural effusion--direct costs in a Dutch hospital. Respiration. 2013;86:224-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Penz ED, Mishra EK, Davies HE, Manns BJ, Miller RF, Rahman NM. Comparing cost of indwelling pleural catheter vs talc pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest. 2014;146:991-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Olden AM, Holloway R. Treatment of malignant pleural effusion: PleuRx catheter or talc pleurodesis A cost-effectiveness analysis. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:59-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |