Revised: March 30, 2012

Accepted: April 18, 2012

Published online: April 28, 2012

Pulmonary amyloidosis is uncommon and is usually associated with systemic amyloidosis. Localized pulmonary involvement in amyloidosis without systemic amyloidosis is even rarer; it is generally tracheobronchial or parenchymal in location. Parenchymal pulmonary amyloidosis is generally asymptomatic and an incidental finding, presenting as nodules varying in size and number, unilateral or bilateral. We present an unusual case of primary bilateral pulmonary nodular amyloidosis in an elderly female.

- Citation: Bhavsar T, Huang Y, Gaughan C, Inniss S, Thomas R. Bilateral pulmonary nodular amyloidosis: A case report and review of the literature. World J Respirol 2012; 2(2): 6-8

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6255/full/v2/i2/6.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5320/wjr.v2.i2.6

Amyloidosis is characterized by abnormal extracellular deposits of light chain proteins of monoclonal immunoglobulins[1]. Amyloid deposition may occur in the kidney, liver, spleen, lung, gastrointestinal tract, endocrine organs, skin, heart or the autonomous nervous system. Amyloidosis involving the respiratory tract occurs in 4 histopathologic forms: (1) focal deposits in the tracheobronchial tree; (2) diffuse parenchymal deposits; (3) single or multiple parenchymal nodules; and (4) senile[1,2]. The mechanism for the deposition of amyloid is unclear. Pulmonary amyloid nodules are frequently seen in older patients with an average age in the sixth decade[3]. They occur more frequently in the lower lobes[3] and may be asymmetrical when present bilaterally[4]. Often found incidentally on chest radiographs[3], these may be confused with neoplasms, pulmonary edema, diffuse interstitial fibrosis or tuberculosis.

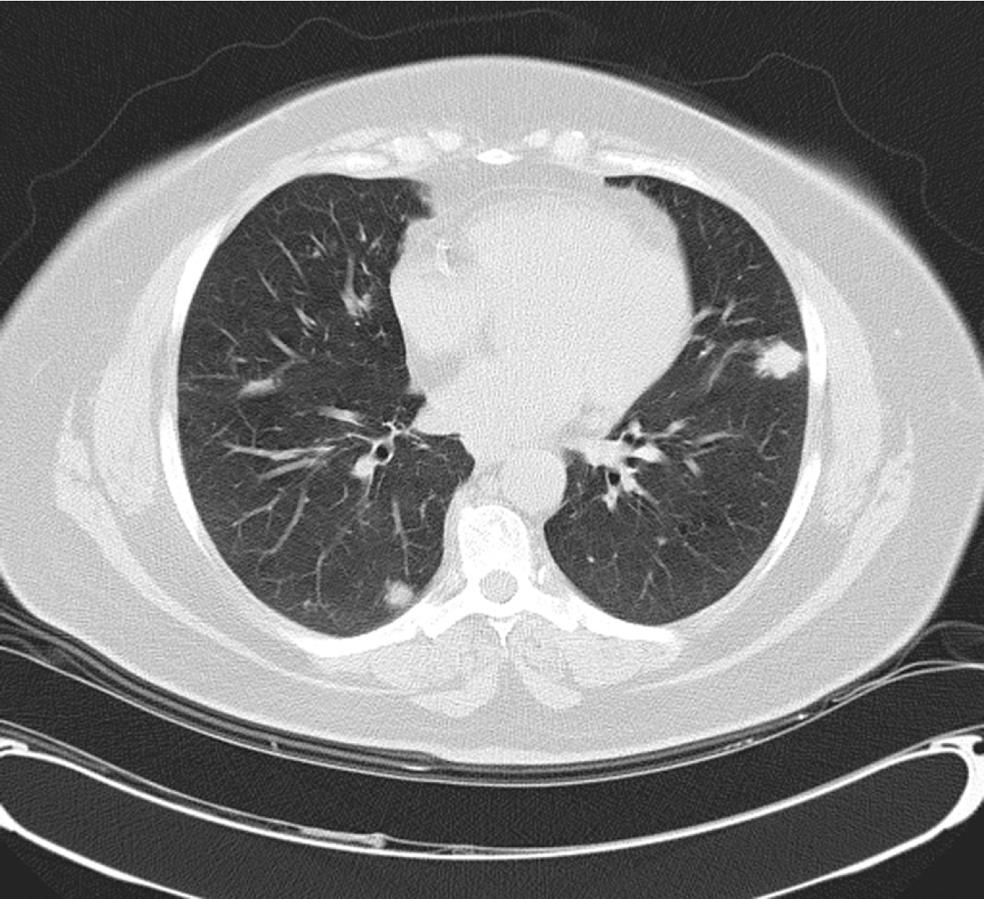

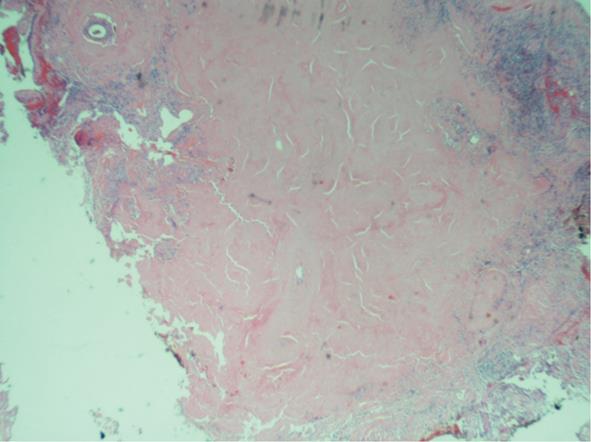

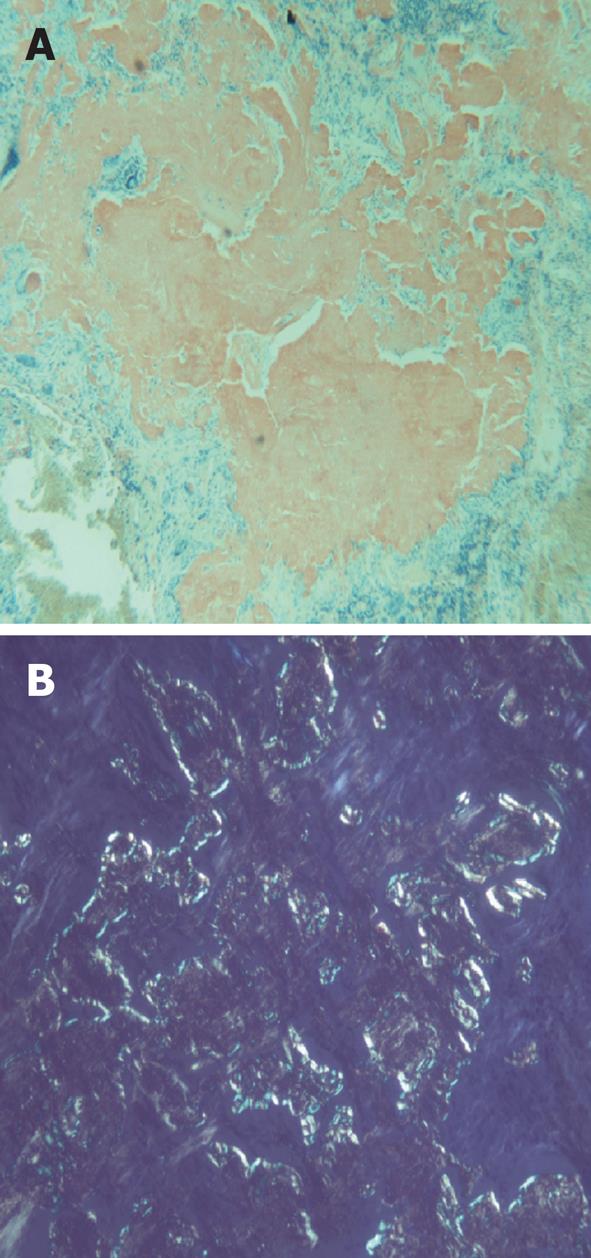

A 59-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension and sleep apnea presented to her primary care physician with shortness of breath of 1 wk duration. The shortness of breath was present at rest, exacerbated by strenuous activities and relieved by rest. The social history was relevant for a 45-pack year cigarette smoking. The hematological and biochemical parameters were within normal limits. A computed tomography (CT)-scan of the chest showed an 11-mm nodule in the lower lobe of the right lung. A follow up CT-chest scan 6 mo later revealed an increase in the size of the nodule to 16.5 mm. The patient was referred to the Temple Lung Centre for further evaluation. A chest X-ray and CT-scan after 3 mo showed multiple bilateral nodular opacities in the mid- and lower-lung zones and small subpleural nodules. A repeat CT-scan after 6 mo revealed an increase in size of the nodules that were now present in all lobes of both lungs, and ranged from 7 to 17 mm in diameter (Figure 1). A CT-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) specimen attempted on a right middle lobe nodule was insufficient for diagnosis. Another CT-guided FNA on a left lung nodule was performed that showed rare clusters of epithelial cells with mild nuclear atypia admixed with mesothelial cells, macrophages, bronchial cells and lymphocytes. The patient underwent an elective wedge resection of the right upper lobe that was studded with multiple nodules by a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, with biopsies of other nodules. The intraoperative pathologic evaluation (frozen section examination) of the nodule revealed eosinophilic material suggestive of amyloid. Pathologic examination of the right upper lobe wedge resection showed multiple firm nodules ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 cm in greatest dimension. Histologically, nodules of acellular eosinophilic amorphous material (Figure 2) were identified in the lung parenchyma associated with a foreign body giant cell reaction; these changes were not present in the bronchi. These deposits were confirmed as amyloid by Congo red (Figure 3A) and Crystal violet stains. Examination under cross-polarized light demonstrated the characteristic apple-green birefringence (Figure 3B). The stains for acid-fast organisms (Ziehl-Neelsen), fungi (GMS) and bacteria (Gram) on these nodules were negative. Serum and urine electrophoresis did not show any evidence of monoclonal gammopathy. Multiple biopsies from other organs were negative for amyloid, excluding systemic deposition. These results were diagnostic for primary nodular pulmonary amyloidosis. The benign course of the disease and the patient’s asymptomatic state at the time of discharge dictated no further immediate treatment.

Pulmonary amyloidosis may be associated with systemic amyloidosis or may be confined to the lung. Localized pulmonary amyloidosis is defined as amyloid deposition isolated to the respiratory tract and does not include amyloidosis associated with systemic deposition (primary, secondary, or familial). Localized pulmonary amyloidosis may involve the tracheobronchial tree or pulmonary parenchyma in a nodular or diffuse distribution.

Amyloid deposits in pulmonary amyloidosis may be either composed of amyloid light chain (AL) or associated with amyloid A protein (AA), AL deposition accounts for 63%-80% of cases[3]. Literature on the distribution patterns of primary pulmonary amyloidosis is scant because of the relative rarity of the condition.

Localized pulmonary amyloidosis without systemic deposition is rare, and is either tracheobronchial or parenchymal in location[1,2]. While some authors[3] have reported parenchymal nodular amyloid to be more common than tracheobronchial, others[5] have reported the converse.

Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis is usually found incidentally on chest radiographs in asymptomatic older adults. Amyloid nodules have no distinctive radiographic characteristics and can be single or multiple, usually peripheral lesions[3,5]. There were multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules identified on a CT-scan in our case. On the basis of the follow up CT-scans that showed an increase in the size and number of the pulmonary nodules since the initial examination, metastatic lesions were suspected.

The amyloid nodules in the lungs may present with symptoms attributable to mass effects, such as cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, airway obstruction, respiratory distress or bronchiectasis[2,6]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, attributed to the patient’s long smoking history might have produced dyspnea in our patient; the amyloid nodules were probably asymptomatic. Narrowing of airways can cause wheezing, distal atelectasis, recurrent pneumonia or lobar collapse.

Solitary nodules may be mistaken for endobronchial neoplasia[7] on imaging and bronchoscopy. Indeed, there are no distinctive radiologic features to distinguish amyloidosis from lung malignancy, tuberculosis, silicosis, sarcoidoisis or hamartomas[8].

The amyloid deposits are thought to originate in the muscular wall of small blood vessels, and as they enlarge, they spread into the parenchyma as nodules. In diffuse pulmonary amyloidosis, the vascular involvement appears to extend to the entire parenchyma, and in the tracheobronchial disease, the site of origin is uncertain. The nodules in our patient ranged from less than a centimeter to 1.7 cm in size. Even though amyloid nodules as large as 15 cm has been reported[3], most range from 0.4 to 5 cm with an average size of 3 cm. Though these nodules may often ossify, calcify or cavitate[9], no such changes were seen in our case.

FNAs have an extremely low yield due to the consistency of amyloid not lending itself to being aspirated. CT-guided biopsies have a better chance of providing diagnostic material; however, most cases of pulmonary amyloidosis have been diagnosed only following surgical resection or at autopsy[10]. In our case, surgical resection of the nodule was performed due to a high index of suspicion of malignancy, and the lack of diagnostic material from the FNAs. Since, the intraoperative examination of the nodule was suggestive of amyloid, further surgery was avoided.

In conclusion, although uncommon, localized nodular pulmonary amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a nodule or nodules in the lung. Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis is characterized by a more benign course than tracheobronchial and diffuse parenchymal types[10]. Most of the patients remain stable over a long period of time[1,11] and therapy is not usually required. Surgery is often necessary for diagnosis; sometimes a wedge resection is required to treat obstructive symptoms or recurrent pneumonia[12,13]. Its primary importance lies in its benign, generally asymptomatic course, in contrast to most infectious or neoplastic diseases with an identical radiologic appearance.

Peer reviewer: Hui-Ying Wang, MD, PhD, Division of Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, 2nd Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, No. 88 Jiefang Road, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China

S- Editor Zhao R L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Cordier JF, Loire R, Brune J. Amyloidosis of the lower respiratory tract. Clinical and pathologic features in a series of 21 patients. Chest. 1986;90:827-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Möllers MJ, van Schaik JP, van der Putte SC. Pulmonary amyloidoma. Histologic proof yielded by transthoracic coaxial fine needle biopsy. Chest. 1992;102:1597-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hui AN, Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Wehunt WD. Amyloidosis presenting in the lower respiratory tract. Clinicopathologic, radiologic, immunohistochemical, and histochemical studies on 48 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:212-218. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Holmes S, Desai JB, Sapsford RN. Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis: a case report and review of literature. Br J Dis Chest. 1988;82:414-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rubinow A, Celli BR, Cohen AS, Rigden BG, Brody JS. Localized amyloidosis of the lower respiratory tract. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:603-611. [PubMed] |

| 6. | O'Regan A, Fenlon HM, Beamis JF, Steele MP, Skinner M, Berk JL. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis. The Boston University experience from 1984 to 1999. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:69-79. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Cotton RE, Jackson JW. Localized amyloid 'tumours' of the lung simulating malignant neoplasms. Thorax. 1964;19:97-103. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Zennami S, Niwa H, Yamakawa Y, Ichimura H, Masaoka A. [Recurrence of AL type primary localized pulmonary amyloidosis]. Kyobu Geka. 1996;49:167-171. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Suzuki H, Matsui K, Hirashima T, Kobayashi M, Sasada S, Okamato N, Kitai N, Kawahara K, Fukuda H, Komiya T. Three cases of the nodular pulmonary amyloidosis with a longterm observation. Intern Med. 2006;45:283-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Guidelines Working Group of UK Myeloma Forum; British Commitee for Standards in Haematology, British Society for Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of AL amyloidosis. Br J Haematol. 2004;125:681-700. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hiroshima K, Ohwada H, Ishibashi M, Yamamoto N, Tamiya N, Yamaguchi Y. Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis associated with asbestos exposure. Pathol Int. 1996;46:66-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Utz JP, Swensen SJ, Gertz MA. Pulmonary amyloidosis. The Mayo Clinic experience from 1980 to 1993. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:407-413. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Thompson PJ, Citron KM. Amyloid and the lower respiratory tract. Thorax. 1983;38:84-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |