Published online Dec 20, 2019. doi: 10.5319/wjo.v8.i2.12

Peer-review started: June 27, 2019

First decision: August 7, 2019

Revised: August 26, 2019

Accepted: November 26, 2019

Article in press: November 26, 2019

Published online: December 20, 2019

Processing time: 188 Days and 4.2 Hours

Synovial osteochondromatosis is a rare but benign condition that can result in significant impairment of joint functionality. This case report documents an uncommon presentation of this disorder occurring within the temporomandibular joint, causing the patient significant pain, trismus, and difficulty with daily activities such as eating and speaking. A review of the literature including disease mechanisms and previously documented cases is included to provide comprehensive background for clinical decision-making.

A 48-year-old male patient presented with a 3-mo history of trismus, crepitus with jaw movement and significant pain while chewing. Physical examination revealed a firm mass and tenderness to palpation at the right temporomandibular joint. Further workup revealed a bilobed mass extending into the joint space as well as significant bony erosion of the glenoid fossa. The patient underwent mass excision with joint reconstruction and pathology revealed synovial osteochondromatosis. The patient reported significant improvement in his symptoms postoperatively.

This report outlines the investigative approach and treatment course of synovial osteochondromatosis. The positive outcome following surgical intervention in this case emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and the potential for improvement in quality of life of this patient population.

Core tip: Synovial osteochondromatosis is a rare condition that arises from metaplasia and proliferation of synovial cells lining a joint space, which can impair joint function. It can be easily overlooked when working up non-specific symptoms such as preauricular pain and swelling. We present the case of a 48-year-old man with a history of significant unilateral temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain, trismus, and dysphagia who was found to have synovial osteochondromatosis of the TMJ with erosion of the glenoid fossa. The patient underwent resection of the mass and TMJ reconstruction with a rib cartilage graft, resulting in alleviation of symptoms.

- Citation: Romero N, Mulcahy CF, Barak S, Shand MF, Badger CD, Joshi AS. Synovial osteochondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: A case report. World J Otorhinolaryngol 2019; 8(2): 12-18

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6247/full/v8/i2/12.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5319/wjo.v8.i2.12

Synovial osteochondromatosis is a condition in which the synovial cells lining a joint space undergo metaplasia and proliferation, resulting in nodular masses, which may ossify within the joint capsule. Ultimately several loose or pedicled bodies form within the joint and cause significant symptoms and impairment of joint functionality. Affected regions most commonly occur within the axial skeleton, including the knee or shoulder capsule[1]. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is rarely affected and has only been documented in about 100 cases over the last 20 years[2,3]. Etiology of this condition is unknown, but it is hypothesized to involve abnormal expression of specific growth factors and cytokines[4,5]. This disease is generally monoarticular and tends to present in adults. Involvement of the TMJ is more common in women than men, most often occurring between the ages of 30 and 60[6]. Although considered a benign condition, synovial osteochondromatosis carries a risk of aggressive and progressive bone erosion which can extend intracranially and even invade the dura[3]. There is also a small incidence of malignant transformation to chondrosarcoma[7].

Patients with synovial osteochondromatosis of the TMJ often present with unilateral pain, malocclusion, and swelling[8-10]. Evaluation of these patients should include comprehensive history, physical, imaging studies, and cytological studies of the joint capsule tissue or fluid. Definitive treatment for synovial osteochondromatosis is surgical removal of the nodules or loose bodies from the joint capsule and often partial synovectomy[11]. Removal of the growths relieves symptoms as well as decreases the risk of possible progression to chondrosarcoma and further degeneration of the joint. In cases with concurrent bone erosion, surgical reconstruction of the mandible or temporal bones may also be required[3].

A 48-year-old male patient was referred for otolaryngology evaluation by his dentist after complaining of trismus, crepitus with jaw movement, significant pain with chewing, and development of a right-sided facial mass.

The patient’s symptoms had started about three months ago and he had seen several physicians previously who provided reassurance and conservatively managed his symptoms. The pain was localized to the right side and aggravated by jaw movements, particularly opening the mouth. He had no constitutional symptoms. Clinical examination revealed a firm mass in the pre-auricular region with tenderness to palpation at the right temporomandibular joint. No obvious facial asymmetry was present at rest. All cranial nerves appeared intact.

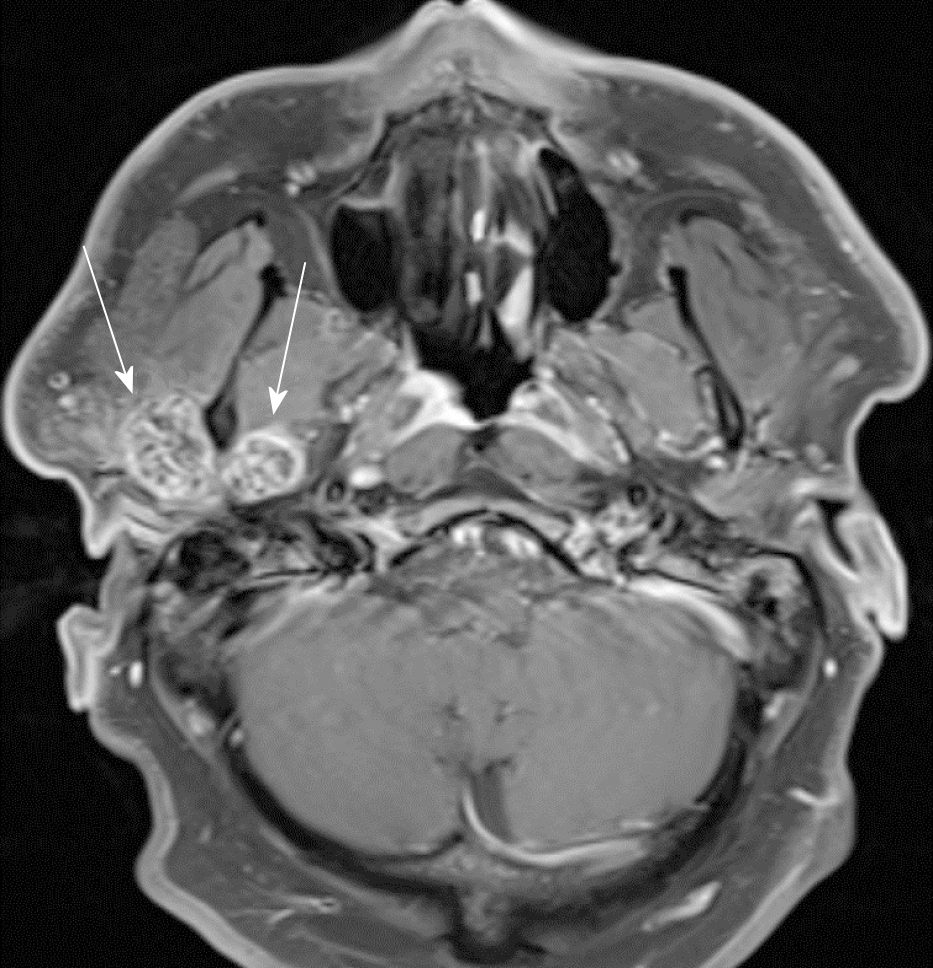

Several imaging studies were obtained. A CT scan of the face demonstrated a bilobed mass extending into the joint space on either side of the mandibular condyle measuring 1.7 cm by 1.2 cm medially and 2.6 cm by 1.6 cm laterally (Figure 1). Additional features included significant bony erosion of the middle fossa floor and glenoid fossa, as well as several cysts present in the subchondral bone on the temporal side of the TMJ. T1 and STIR magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences also indicated marked joint capsule distention and joint effusion (Figure 2). The mass appeared to be well circumscribed and did not appear to invade adjacent soft tissue structures.

A fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed, which revealed a matrix-producing lesion with osteoclast-like giant cells and cellular atypia of undetermined significance.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is synovial osteochondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with significant erosion of the glenoid fossa.

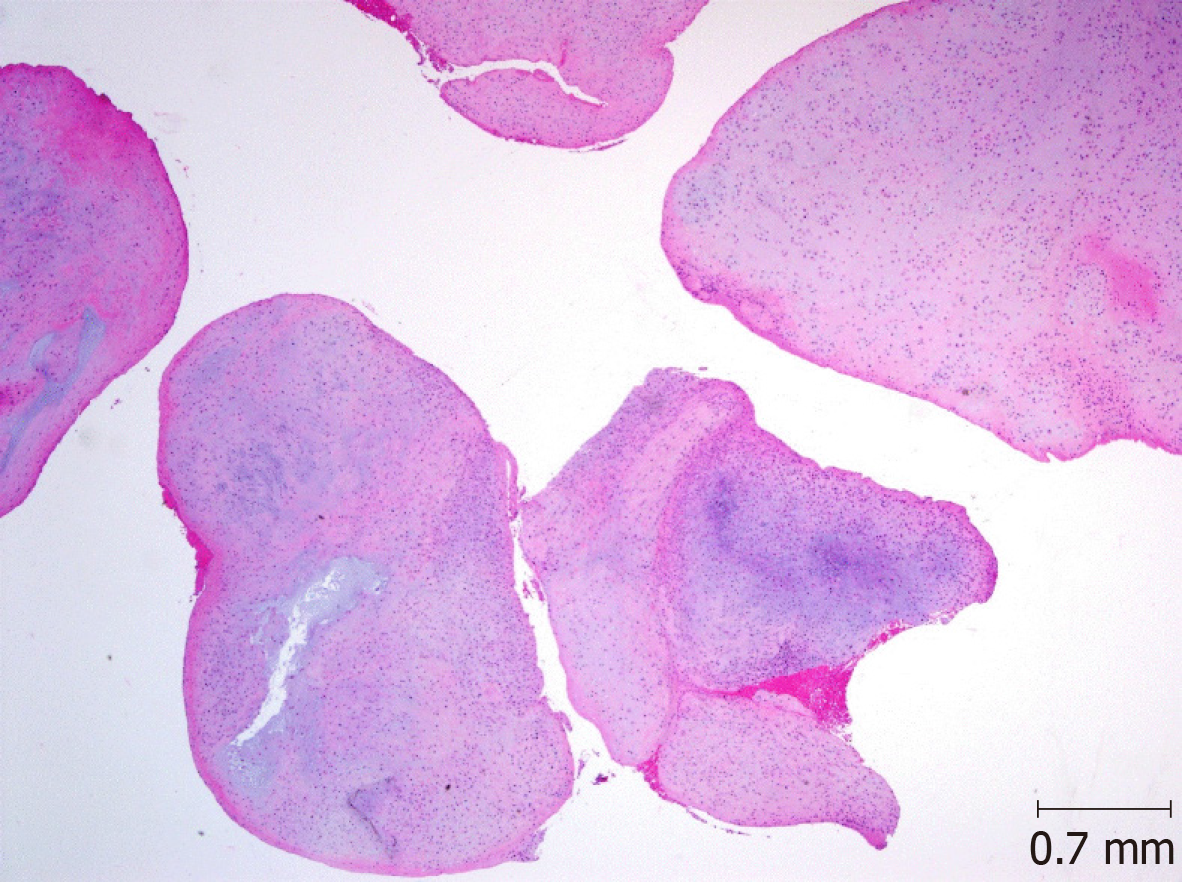

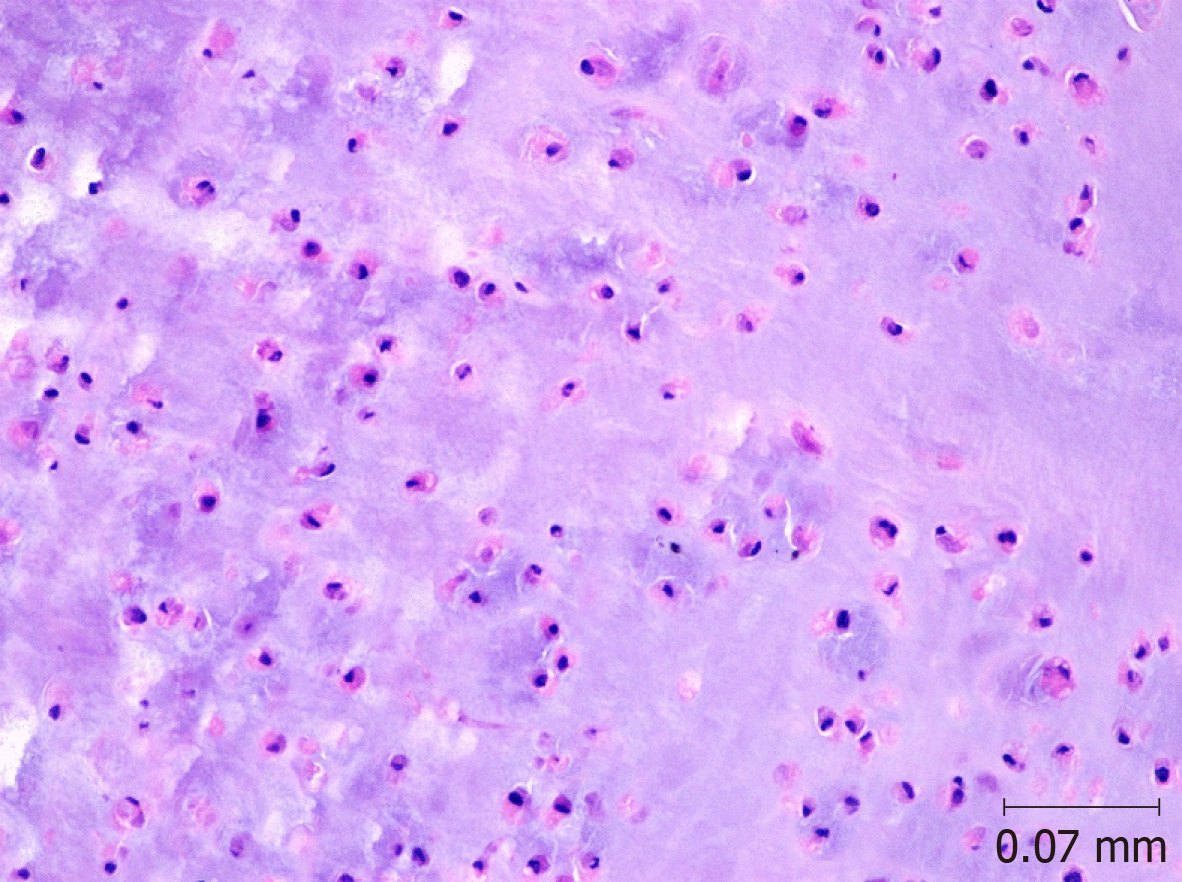

Surgical intervention was indicated for this patient given his failed response to medical management and aggressive nature of bony erosion displayed on imaging. The patient underwent surgical removal of the mass and reconstruction of the joint. A pre-auricular incision was made and a pedicled temporoparietal flap was used to fully expose the condylar mass and joint capsule. The TMJ capsule was opened and revealed well-formed pieces of cartilage which were removed. Circumferential subperiosteal resection of condylar neck was performed to completely remove the adherent mass. A freer elevator was utilized to circumferentially dissect the mass off of the condyle. Sharp excision was required to free the mass from surrounding soft tissue. Care was taken to preserve the external carotid artery. The mass was delivered in a complete, but piecemeal fashion. It became apparent that the mass had filled the superior aspect of the infratemporal fossa and extended into the parapharyngeal space. Following the resection, a rib cartilage graft was used to resurface the superior aspect of the glenoid fossa. The temporoparietal flap was wrapped around the cartilage graft for vascular support and the graft was inset into the joint defect. The condyle itself was preserved adequately preserved during excision of the mass so that condyle reconstruction was not necessary. Specimens acquired from within the TMJ capsule (Figure 3), the mandibular condyle, and surrounding soft tissue were sent for intraoperative frozen-section pathology analysis which showed no evidence of malignancy.

The postoperative course of this patient was uncomplicated. At his first post-operative visit two weeks after surgery, he reported significant improvement in symptoms, and his facial movement was symmetric. He was tolerating a soft diet with only moderate soreness. Physical exam revealed residual swelling and a well-healing facial incision. He was referred for physical therapy for restoration of joint motility. Final pathology of surgical specimens showed lobules of cartilaginous tissue, lacking cytologic atypia, hypercellularity or mitosis, consistent with synovial osteochondromatosis (Figures 4, 5). Unfortunately, after his first post-operative visit, the patient was lost to follow up.

Synovial osteochondromatosis is a non-neoplastic proliferation of joint cartilage, which results in the formation of nodular and sometimes ossified bodies within the joint space. Dysregulated tissue growth factors and cytokines such as TGF-B3, FGFR-3 and IL-6 are involved in the proposed mechanism of over-stimulating active chondrocytes to proliferate and undergo metaplasia[4,5]. The disease process can be divided into several stages of growth: (1) Proliferation of the synovial lining resulting in nodular pedicled growths; (2) Release of the nodules into the joint space, detachment from the synovium; and (3) Ossification of the nodules within the joint space, with concurrent decline in synovial proliferation[12]. Symptoms most often present in the second and third phase of growth when the bodies become loose within the joint, ossify and cause impairment of joint functionality. Impairment of cranial nerve function generally indicates most advanced disease[6,8,10].

Although synovial osteochondromatosis rarely occurs in the facial bones, the TMJ is an important region of occurrence, which requires special consideration when evaluating patients with a pre-auricular mass or symptoms of malocclusion, crepitus and jaw pain. In many cases, patients experience symptoms for years before correct diagnosis can be made and surgical intervention performed[9]. Presenting complaints are often vague or non-specific, and late diagnosis occurs frequently due to symptom overlap with more common conditions such as temporomandibular joint disorder. Physical findings may include swelling and tenderness to palpation in the preauricular area, as well as decreased range of motion. Collaboration among colleagues in primary care, dentistry and surgery is therefore crucial to the timely diagnosis and proper management of these patients. Degenerative arthritis is a common complication due to the repeated injury of the joint[13,14]. Delay in diagnosis has the potential to cause significant complications and morbidity for the patient due to the possibility of local or intracranial invasion as well as permanent loss of joint function[8,11]. Invasion into the cranium can also result in permanent cranial nerve injuries, particularly facial nerve deficits[15]. The differential diagnosis of a mass within the TMJ includes many types of neoplastic growths and it is therefore important to rule out malignancy when evaluating these patients.

Diagnosis of synovial osteochondromatosis of the TMJ requires multiple imaging modalities, typically including CT and MRI. Common findings include expansion and effusion within the joint space as well as cartilaginous nodules or loose bodies[15]. MRI may be necessary for diagnosis of early disease in which the nodules have not yet ossified or calcified to better characterize joint effusion, capsular swelling and possible disruption of soft tissues[9,16]. Surrounding bony structures should be carefully evaluated to identify the likelihood of intracranial erosion and dural involvement[11,17]. Other degenerative changes such as subchondral cysts may also be evident within the joint, as in this case. Preoperative biopsy for tissue analysis to assess for malignancy is beneficial[3]. Histologic findings can confirm loose bodies within the joint space or pedunculated masses attached to the joint capsule lining[18].

Despite its classification as a benign condition, synovial osteochondromatosis occurring in the TMJ can lead to local erosion and complications from intracranial invasion[11]. In addition, the disorder carries a small risk of progression to malignant chondrosarcoma, and therefore prompt diagnosis and treatment is crucial[7,8]. Surgical intervention remains the most appropriate treatment due to the lack of effective medical management and the potentially aggressive nature of the disease process. Both arthroscopic and open technique surgeries have been utilized in the process of mass removal. Arthroscopic approaches are less morbid and may be useful for diagnosis, however an open arthrotomy may be more appropriate if the masses are large or numerous[19,20]. Cases with intracranial invasion typically require open surgical excision and reconstruction[3,15]. In this case as well as others, the extent and stage of the disease may require condylectomy and reinforcement of the glenoid fossa to restore proper structural support[3].

Outcomes following surgical intervention reported in the literature have been overwhelmingly positive. Patients tend to report significant improvement in symptoms and reduction in pain[8,15]. Patients benefit from postoperative physical therapy to improve joint motility and help correct any previous malocclusion. Regular follow up should be encouraged for these patients due to the reported recurrence rate of approximately 11%[12]. Recurring disease should increase clinical suspicion for malignant process and careful re-evaluation should be performed.

Synovial osteochondromatosis is a rare condition and is easily overlooked when working up non-specific symptoms such as preauricular pain and swelling. The lack of response to medical management and the positive outcomes following surgical intervention reinforce the potential benefit to patients suffering from this treatable disorder. Treatment not only provides symptomatic relief and improved quality of life, but also decreases likelihood of progressive joint injury, intracranial erosion, and malignant transformation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Ophthalmology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chhabra N, Ciuman RR, Dhiwakar M S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Miller MV, King A, Mertens F. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. 3rd ed. (Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors). Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2002. |

| 2. | Reed LS, Foster MD, Hudson JW. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: a case report and literature review. Cranio. 2013;31:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pau M, Bicsák A, Reinbacher KE, Feichtinger M, Kärcher H. Surgical treatment of synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with erosion of the skull base: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43:600-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li Y, El Mozen LA, Cai H, Fang W, Meng Q, Li J, Deng M, Long X. Transforming growth factor beta 3 involved in the pathogenesis of synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibular joint. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tojyo I, Yamaguti A, Ozaki H, Yoshida H, Fujita S. The expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in synovial osteochondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49:591-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mikami T, Aomura T, Ohira A, Kumagai A, Hoshi H, Takeda Y. Three case reports of synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibular joint: histopathologic analyses of minute cartilaginous loose bodies from joint lavage fluid and comparison with phase II and III cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:2099-2105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Coleman H, Chandraratnam E, Morgan G, Gomes L, Bonar F. Synovial chondrosarcoma arising in synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:304-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shah SB, Ramanojam S, Gadre PK, Gadre KS. Synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibular joint: journey through 25 decades and a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2795-2814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guarda-Nardini L, Piccotti F, Ferronato G, Manfredini D. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: a case description with systematic literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:745-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koyama J, Ito J, Hayashi T, Kobayashi F. Synovial chondromatosis in the temporomandibular joint complicated by displacement and calcification of the articular disk: report of two cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1203-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Campbell DI, De Silva RK, De Silva H, Sinon SH, Rich AM. Temporomandibular joint synovial chondromatosis with intracranial extension: a review and observations of patient observed for 4 years. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2247-2252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Phelan E, Griffin J, Timon C. Temporomandibular joint osteochondromatosis: an unusual cause of preauricular swelling. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:63-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sink J, Bell B, Mesa H. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: clinical, cytologic, histologic, radiologic, therapeutic aspects, and differential diagnosis of an uncommon lesion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117:e269-e274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fuller E, Bharatha A, Yeung R, Kassel EE, Aviv RI, Howard P, Symons SP. Case of the month #166: synovial chondromatosis of the temporal mandibular joint. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2011;62:151-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Holmlund AB, Eriksson L, Reinholt FP. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: clinical, surgical and histological aspects. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang P, Tian Z, Yang J, Yu Q. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: MRI findings with pathological comparison. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41:110-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang H, Zhang J, He X, Niu Y. Synovial sarcoma in the oral and maxillofacial region: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peyrot H, Montoriol PF, Beziat JL, Barthelemy I. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: CT and MRI findings. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2014;95:613-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, Jiang B, Zhou Q, Jin JM, Yun B, Chen ZZ. Arthroscopic management for synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: a retrospective review of 33 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:2106-2113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhu Y, Zheng C, Deng Y, Zhang Y, Hu X. Arthroscopic surgery for removal of 112 loose bodies of synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:2166-2169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |