Published online Feb 28, 2015. doi: 10.5319/wjo.v5.i1.30

Peer-review started: September 28, 2014

First decision: November 19, 2014

Revised: December 13, 2014

Accepted: December 29, 2014

Article in press: December 31, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2015

Processing time: 137 Days and 10.2 Hours

AIM: To precise the clinical characteristics of rhinosinusitis in pediatric population, their complications and therapeutic approaches.

METHODS: All infants younger than 15 years admitted to the Ear, Nose and Throat Department of the Military Hospital of Tunis, Tunisia for a complicated rhinosinusitis between 2006 and 2013 were evaluated. Data related to patients and the disease were collected and analyzed: past medical history, complaints, clinical examination, radiologic findings, therapeutic management and evolution.

RESULTS: Eighteen cases were identified with a mean age of 5.1 years (5 mo to 13 years) (SD ± 3.1). A male preponderance was noted in 72% of the cases. Rhinorrhea and fever were the most common presenting symptoms. Radiological explorations (computed tomography-scan ± magnetic resonance imaging) have been practiced for all of our patients. Orbital involvement was found in 77% of the cases associated with meningitis in 2 cases. Antibiotherapy was prescribed to all our patients. Surgical procedures were performed in 8 cases: endoscopic sinus surgery and/or external drainage of orbital abscess. After an average follow-up period of 2.5 years, 3 of our patients were lost. The ophthalmic sequelae noted in 3 cases (16%) were permanent and caused important functional and social problems. A favourable outcome has been noted in the rest of our patients.

CONCLUSION: Rhinosinusitis can be extremely severe in children requiring urgent radiological imaging and aggressive treatment to avoid orbital and intracranial complications.

Core tip: Rhinosinusitis is a common condition in childhood. However, complicated cases occur less frequently and are potentially life-threatening. The clinical presentation is often modified by a prior antibiotic prescription. In this paper we report our experience in the management of complicated sinusitis in infants and compare it with literature data. Orbito-cranial extension must be suspected in presence of proptosis, Swelling and/or redness of the eye or persistent headache. Urgent contrast-enhanced computed tomography-scan is the recommended initial imaging. Once the diagnosis confirmed, intravenous antibiotherapy should be started. Surgery is indicated in selected cases. A regular follow-up is mandatory.

- Citation: Mardassi A, Mathlouthi N, Mbarek H, Halouani C, Mezri S, Zgolli C, Chebbi G, Mhamed RB, Akkari K, Benzarti S. Complicated sinusitis in children: 18 cases report. World J Otorhinolaryngol 2015; 5(1): 30-36

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6247/full/v5/i1/30.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5319/wjo.v5.i1.30

Acute rhinosinusitis is a relatively common disease affecting both children and adults. Its prevalence rate is between 6% and 12% with viral origin in most cases and a bacterial one in only 0.5%-2%[1]. Fungi have been described as causative agents especially in immunocompromised patients[2,3]. Diagnostic criteria and therapeutic management are still a controversial issue. Complications of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis are uncommon in children, but they can be extremely severe and potentially life threatening[1,4,5]. Mortality rate has decreased significantly from 42% in the 1950s to 12% in the 1990s thanks to medical progress[5].

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of complicated rhinosinusitis in children admitted to the Ear-Nose-Throat Department of the Military Hospital of Tunis Tunisia between 2006 and 2013. The children treated for an acute and non complicated rhinosinusitis by oral therapy and without the need for an overnight stay in hospital were excluded from the study. Parameters recorded were epidemiologic data, clinical presentation, biological results, radiological investigations, localization of affected sinuses, types and sites of complications, therapeutic management and outcomes.

In this retrospective and descriptive study, 18 patients have been reported. For quantitative data, the mean and the standard deviation have been obtained. For qualitative data, the percentage of each sub-group has been calculated. The statistical method is adequate because there was no comparison between the variables. P-value was not calculated since no hypotheses are tested in the study.

Eighteen children with complicated rhinosinusitis were identified over 8 years (2006 to 2013). Ages ranged from 5 mo to 13 years with an average of 5.1 years (SD ± 3.1). A male preponderance was noted in 72% of the cases. No medical history of allergic rhinitis or sinusitis has been found. Besides, our patients

weren’t suffering from any immunodeficiency disorders. The main complaints reported were: rhinorrhea (16/18; 88.9%), fever (10/18; 55.6%) headache (2/18; 11.1%) and ophthalmic signs (14/18; 77.8%). The duration of symptoms prior to presentation was inferior to 7 d in 71.4% of the cases (2-10 d). Prior antibiotic treatment has been prescribed for 6 patients (33%). The results of the clinical examination are resumed in Table 1.

| Findings | No. of cases | % | |

| Nasal endoscopy | Congestion and pus at the middle meatus | 5 | 27.78 |

| Purulent discharge at the nasopharynx | 2 | 11.12 | |

| Polypoïd lesion | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Ophthalmic exam | Congestion of the upper eyelid | 8 | 44.45 |

| Swelling and/or redness at the medial angle of the eye | 6 | 33.34 | |

| limitation in the medial ocular movement | 5 | 27.78 | |

| Signs of meningeal irritation | 2 | 11.12 |

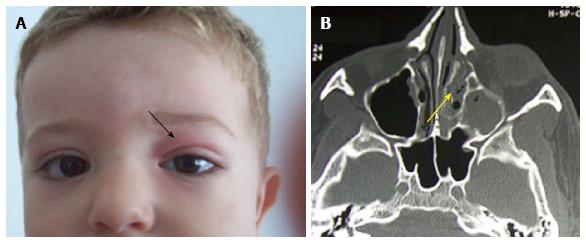

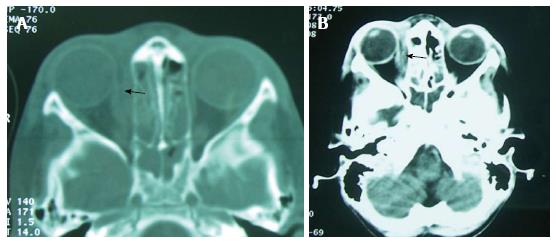

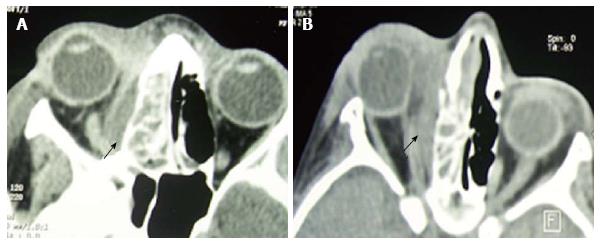

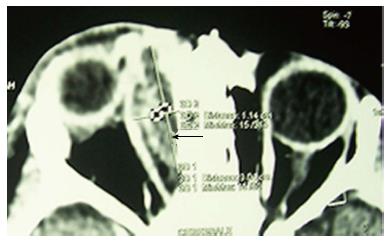

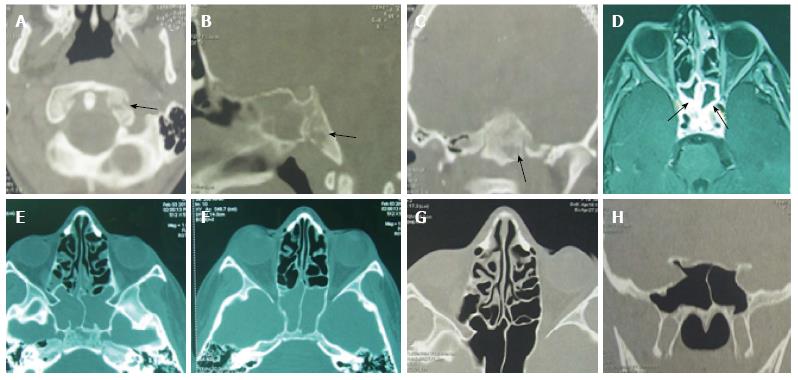

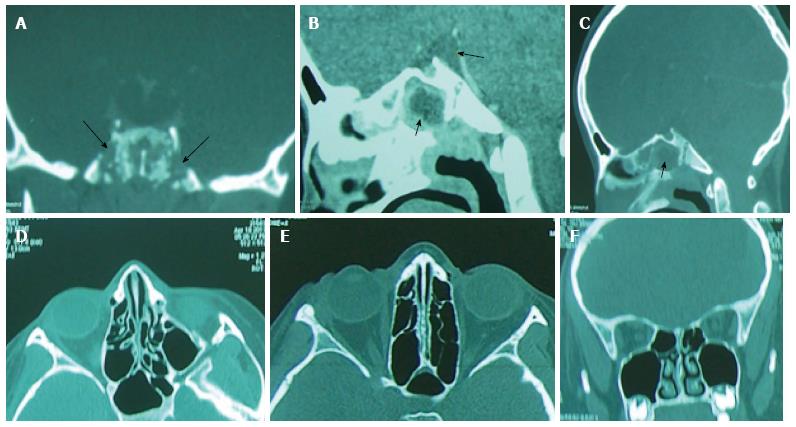

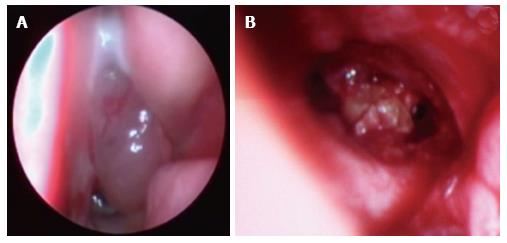

Brain and sinus CT-scan have been practiced for all our patients and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 2 cases. The most frequent localization of sinusitis was ethmoïd (77%), ethmoïd + maxillary (33%) and the sphenoid sinus (11%). According to Chandler’s classification, orbital complications were divided into: class II (7 cases; 38%), class III (4 cases; 22%), class IV (2 cases; 11%) and class V (1 case; 5%) (Table 2) (Figures 1-4). In case of sphenoiditis, different degrees of bony lysis have been noted (Figures 5 and 6).

| No. of cases | % | ||

| Sites of the lesions | Ethmoïd | 14 | 77.78 |

| Ethmoïd + maxillary | 6 | 33.34 | |

| Sphenoid | 2 | 11.12 | |

| Lytic bone lesions | 2 | 11.12 | |

| Orbital complications | Cass II: orbital cellulitis | 7 | 38.89 |

| Class III: periosteal abscess | 4 | 22.23 | |

| Class IV: orbital abscess | 2 | 11.12 | |

| Class V: cavernous sinus thrombosis | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Meningeal reaction | 2 | 11.12 |

Laboratory tests found leukocytosis in 9 cases and elevation of the C-reactive-protein in 6 cases (33%).

Medical treatment was based on intravenous antibiotherapy for all the patients. Intravenous heparin at curative dose has been administrated in the case of the cavernous sinus thrombosis for 3 wk. A complementary surgical intervention was indicated in 8 cases. All medical and surgical treatments are detailed in Table 3.

| No. of cases | % | ||

| Medical treatment | Cefotaxime (100 mg/kg/j) + fosfomycin (100 mg/kg/j) | 14 | 77.78 |

| Cefotaxime + fosfomycin + amikacin (15 mg/kg/j) | 2 | 11.12 | |

| Cefotaxime (200 mg/kg/j) + vancomycine (60 mg/kg/j) | 2 | 11.12 | |

| Intravenous heparin (Bolus 50 units/kg, 2 units/kg per hour) | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Surgery | External medial orbitotomy | 4 | 22.23 |

| Endonasal orbitotomy | 2 | 11.12 | |

| Sphenoidotomy | 2 | 11.12 |

The outcomes were almost good in cases of class II and III ethmoiditis after medical or medicosurgical treatment. The clinical signs (fever, pain, swelling) disappeared in a period of 5 to 10 d. No ophthalmic complications have been noted among this group of patients.

For class IV “Chandler” complications (orbital abscess = 2 patients) and for the cavernous sinus thrombosis (1 case), severe ophthalmic sequelae have been diagnosed: ophtalmoplegia, loss of vision and 3rd, V1 and V2 cranial nerve palsies.

The 2 cases of sphenoiditis have benefited from endoscopic sphenoidotomy with intravenous antibiotherapy (Figure 7). The computed tomography (CT)-scan showed during the follow-up, a notable regression of the inflammatory lesions (Figures 5 and 6). The regression of the lytic bone lesions have taken several months but without notable clinical signs.

After an average follow-up period of 2.5 years, 3 of our patients were lost. The ophthalmic sequelae noted in 3 cases (16%) were permanent and caused important functional and social problems. A favourable outcome has been noted in the rest of our patients.

Rhinosinusitis is one of the most common diseases during childhood, accounting for nearly a quarter of all pediatric antibiotic prescriptions[6]. It is most of the time efficiently treated with nasal decongestants with or without antibiotics. Recovery is obtained in most cases of acute rhinosinusitis, however, between 5% and 10% will go on to develop complications[7]. Complicated rhinosinusitis has been described as the adverse progression of bacterial infection beyond the paranasal sinuses. Complications are divided into orbital, intracranial or mixed manifestations[1,8]. Sinus infection can spread through either direct, hematogenous, or by retrograde extension, along the valve-less diploic veins[4,5]. Orbital complications are more common than intracranial ones and are often classified using the criteria of Chandler[1,4,5]. Briefly, class I is “preseptal cellulitis”, class II is “orbital cellulitis”, class III is “subperiosteal abscess”, class IV is “orbital abscess” and class V is “cavernous sinus thrombosis”[9]. Intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis consist of meningitis, subdural empyema, epidural and cerebral abscess, and venous sinus thrombosis[5]. The most common of this type of complications is different from one series to another. It was subdural empyema in Yew Kwang Ong[5], Skelton[10] and Jones’s series[11], however for Clayman[12] and Giannoni[13] it was cerebral abscess. Orbital complications occur most commonly in younger children[4]. However, the extension to intracranial structures is rare in children under the age of 7 and occurs typically in young adolescents[5,12]. Our finding of male preponderance in orbito-cranial complications of sinusitis is in keeping with literature[1,14,15]. The clinical presentation can be fever, headache, vomiting, chemosis, eye pain, proptosis, cranial nerve palsy, seizures and focal neurological deficit[4]. The symptoms are non-specific initially and the diagnosis may be overlooked for several reasons[1,5]. In most cases of complicated rhinosinusitis in children, previous sinus disease or history of allergic rhinitis is often not found. For Jones[11] this kind of medical history was present in only 10% of his patients and Yew Kwang Ong noted this in 28% of cases[5]. Many patients consult a family physician and take prior antibiotic treatment. This prescription modifies the disease presentation and masks the diagnosis. However behind a swollen eye, a proptosis, or an impaired function of the extraocular muscles, an orbital extension must be suspected[4]. A persistent headache, especially beyond one week, is the most consistent symptom of intracranial involvement[16,17].

The average duration of illness from presentation is 3-5 d[14]. In our series it was inferior to 7 d in 71.4% of cases.

Orbital complications are most commonly secondary to ethmoïd sinus involvement and intracranial injury associated with frontal sinusitis[1].

The diagnosis of rhinosinusitis is clinical[18]. However, when orbital or intracranial complications are suspected, urgent radiological examination is recommended. Contrast-enhanced CT with coronal and axial slices is the initial imaging modality of choice[5,19]. It should be performed, in pediatric patients, with the lowest radiation dose possible allowing a good diagnostic study[19]. Coronal cuts are useful for studying the ostiomeatal unit and the relations between orbit and brain[20]. The contribution of CT is also considerable in delineating bony anatomy for a potential endoscopic sinus surgery[4,20]. MRI is more efficient in soft tissue analysis but its high cost and limited accessibility hinder its routine use[5,20]. In our series it was practiced in only 2 cases. Yew Kwang Ong recommends to practice simultaneously sinus and brain CT when intracranial complications are suspected, and to repeat it if a complication is strongly suspected[5]. In Skelton’s series 50% of children with subdural empyemas had normal scans initially[10].

Bacteriological analysis is required to adjust antibiotic treatment. Polymicrobial or culture negative specimens are not so rare, sterile samples are obtained in 25%-30% of cases[1,4]. In recent years, there is an increase in reports of fungal invasion accompanying rhinosinusitis. These forms were connected with several promoting factors as diabetes, steroidotherapy and immunosuppression[21,22].

A complicated rhinosinusitis is a therapeutic emergency. Once the diagnosis evoked, an adequate treatment should be started. The therapeutic management is divided into medical and surgical treatment. Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics are recommended until definitive culture and sensitivity results are obtained[4,5,20]. The most common germs are Streptococcus species, Anaerobes and Staphylococcus Aureus[4,5,20]. When intracranial complication is associated, used antibiotics must have a good blood brain barrier penetration and should be continued for 4 to 8 wk[5]. The surgical treatment comprises endoscopic sinus surgery, orbital decompression and neurosurgical intervention[4]. It is most commonly indicated when medical therapeutic fails to control the infection[20]. However in cases with intracranial complications, it is recommended to initially operate[1,4,5]. In Yew Kwang Ong’s series[5], repeated drainage was necessary to eradicate the intracranial infection. Kurt Denton Schlemmer[1] prefers external approach to the endoscopic one and indicates surgery in the following cases: proptosis with orbital complications, intracranial complications, sub-periosteal and pre-septal collections, and cellulitis that does not respond to medical management within 24-48 h. In our series, surgery was indicated in 8 cases: external medial orbitotomy (4 cases), endonasal orbitotomy (2 cases) and sphenoidotomy (2 cases) because of a non response to medical treatment, for orbital collections or for associated meningitis.

In complicated acute rhinosinusitis, a follow-up for up to one year is recommended[7]. Thanks to progress in diagnostic tools and therapeutic management, mortality has decreased significantly in developing countries to about 4%-6%[1,4]. However sequelae such as visual deficits or loss, cranial nerve palsies, epilepsy, hemiparesis, seizure, speech and cognitive impairment can unfortunately persist[4,5].

In conclusion, rhinosinusitis is one of the most common infections in the pediatric population but complicated cases are rare. Orbito-cranial involvement carries high morbidity and changes radically the prognosis. It requires a management by a multi-speciality team including pediatrician, radiologist, otolaryngologist, neurosurgeon and ophthalmologist. Good outcomes can be reached given an early diagnosis, based on complete clinical examination and urgent radiological imaging, and aggressive medical and surgical treatments.

Contrary to adults, acute rhinosinusitis are more frequent in children, but with a high risk of severe and potentially life threatening complications.

The study describes the clinical, paraclinical and therapeutic management of rhinosinusitis in pediatric population.

The treatment of rhinosinusitis in children must be very appropriate to the locoregional extension of the disease and guided by endoscopic and radiological findings.

The authors must retain that pediatric rhinosinusitis is a serious disease requiring a precise evaluation of the locoregional extension through radiological exams, intravenous antibiotherapy and, if necessary, a complementary surgical procedures.

SD: Standard deviation; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

It was a well written study.

P- Reviewer: Arsenijevic VA, Cerase A, Ozcan C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Schlemmer KD, Naidoo SK. Complicated sinusitis in a developing country, a retrospective review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:1174-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kumar MM, Poovazhagi V, Anbalagan S, Devasena N. Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis in a child with diabetic ketoacidosis. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:334-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Naeem F, Rubnitz JE, Hakim H. Isolated nasal septum necrosis caused by Aspergillus flavus in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:627-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharma PK, Saikia B, Sharma R. Orbitocranial complications of acute sinusitis in children. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:282-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ong YK, Tan HK. Suppurative intracranial complications of sinusitis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;66:49. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Oxford LE, McClay J. Medical and surgical management of subperiosteal orbital abscess secondary to acute sinusitis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1853-1861. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Patel RG, Daramola OO, Linn D, Flanary VA, Chun RH. Do you need to operate following recovery from complications of pediatric acute sinusitis? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:923-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Slack R, Sim R. Complications of rhinosinusitis. Scott Brown’s Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 7th ed. USA: CRC Press 2008; 1539-1548. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Chandler JR, Langenbrunner DJ, Stevens ER. The pathogenesis of orbital complications in acute sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1970;80:1414-1428. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Skelton R, Maixner W, Isaacs D. Sinusitis-induced subdural empyema. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:1478-1480. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Jones NS, Walker JL, Bassi S, Jones T, Punt J. The intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis: can they be prevented? Laryngoscope. 2002;112:59-63. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Clayman GL, Adams GL, Paugh DR, Koopmann CF. Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis: a combined institutional review. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:234-239. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Giannoni C, Sulek M, Friedman EM. Intracranial complications of sinusitis: a pediatric series. Am J Rhinol. 1998;12:173-178. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Oxford LE, McClay J. Complications of acute sinusitis in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:32-37. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Goytia VK, Giannoni CM, Edwards MS. Intraorbital and intracranial extension of sinusitis: comparative morbidity. J Pediatr. 2011;158:486-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kombogiorgas D, Seth R, Athwal R, Modha J, Singh J. Suppurative intracranial complications of sinusitis in adolescence. Single institute experience and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:603-609. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Germiller JA, Monin DL, Sparano AM, Tom LW. Intracranial complications of sinusitis in children and adolescents and their outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:969-976. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wald ER, Applegate KE, Bordley C, Darrow DH, Glode MP, Marcy SM, Nelson CE, Rosenfeld RM, Shaikh N, Smith MJ. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e262-e280. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hoxworth JM, Glastonbury CM. Orbital and intracranial complications of acute sinusitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2010;20:511-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Amat F. [Complications of bacterial rhino-sinusitis in children: a case report and a review of the literature]. Arch Pediatr. 2010;17:258-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Czecior E, Gawlik R, Jarząb J, Mrówka-Kata K, Sowa P, Iwańska J. The presence of fungal floras in sinuses in chronic sinusitis patients with polyps. Otolaryngol Pol. 2012;66:259-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chakrabarti A, Denning DW, Ferguson BJ, Ponikau J, Buzina W, Kita H, Marple B, Panda N, Vlaminck S, Kauffmann-Lacroix C. Fungal rhinosinusitis: a categorization and definitional schema addressing current controversies. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1809-1818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |