Published online Aug 28, 2013. doi: 10.5319/wjo.v3.i3.108

Revised: June 20, 2013

Accepted: August 12, 2013

Published online: August 28, 2013

Processing time: 123 Days and 1.4 Hours

Although the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap is often used in head and neck reconstruction, the extension of the skin paddle beyond the inferior limits of the muscle has not been well described. We aim to clarify the design and application of this extended flap in head and neck reconstruction. In this retrospective study, consecutive cases of extended pectoralis major myocutaneous flap reconstruction of post-ablative head and neck defects at a single tertiary referral center were included for analysis. In 7 cases an extended pectoralis major flap was utilized, in which the skin paddle was extended beyond the inferior border of the pectoralis major to include the rectus sheath. Skin and soft tissue as well as composite defects of the oral cavity, parotid/temporal region and neck were reconstructed. All flaps healed satisfactorily with no loss of skin viability. The extended pectoralis major myocutaneous flap is robust and has versatile applications for reconstruction of large, high and three dimensionally complex defects in the head and neck region.

Core tip: The current report describes the indications, design and technique of the extended pectoralis major flap in reconstructing challenging defects in the head and neck region. The flap has been shown to be safe and robust, and offers an important reconstructive option.

- Citation: Dhiwakar M, Nambi G. Extended pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction. World J Otorhinolaryngol 2013; 3(3): 108-113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6247/full/v3/i3/108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5319/wjo.v3.i3.108

The pectoralis major flap was first described in 1968[1] and later popularized for head and neck reconstruction by Ariyan[2] in 1979. Due to its ready availability, ease of harvest and reliability, it soon became the choice of reconstruction for post-ablative defects in the head and neck region. Currently however, free tissue transfers, which offer superior pliability and ability to be contoured to the defect, have largely superseded the pectoralis major flap. Nevertheless, the latter retains an important place in contemporary head and neck reconstruction, particularly in resource constrained settings, high risk patients and as salvage after free flap failure.

The principal blood supply to the flap is from the thoracoacromial artery, a branch of the axillary artery that enters the deep muscle surface from beneath the middle third of the clavicle. In most large series, the skin paddle has been limited to within the surface area of the pectoralis major muscle, i.e., territory supplied by the thoracoacromial artery, as extension beyond this border is thought to compromise blood supply[2,3]. In this report, we describe our experience with the extended pectoralis major flap, wherein the skin paddle was extended beyond the inferior border of the pectoralis major to include rectus sheath.

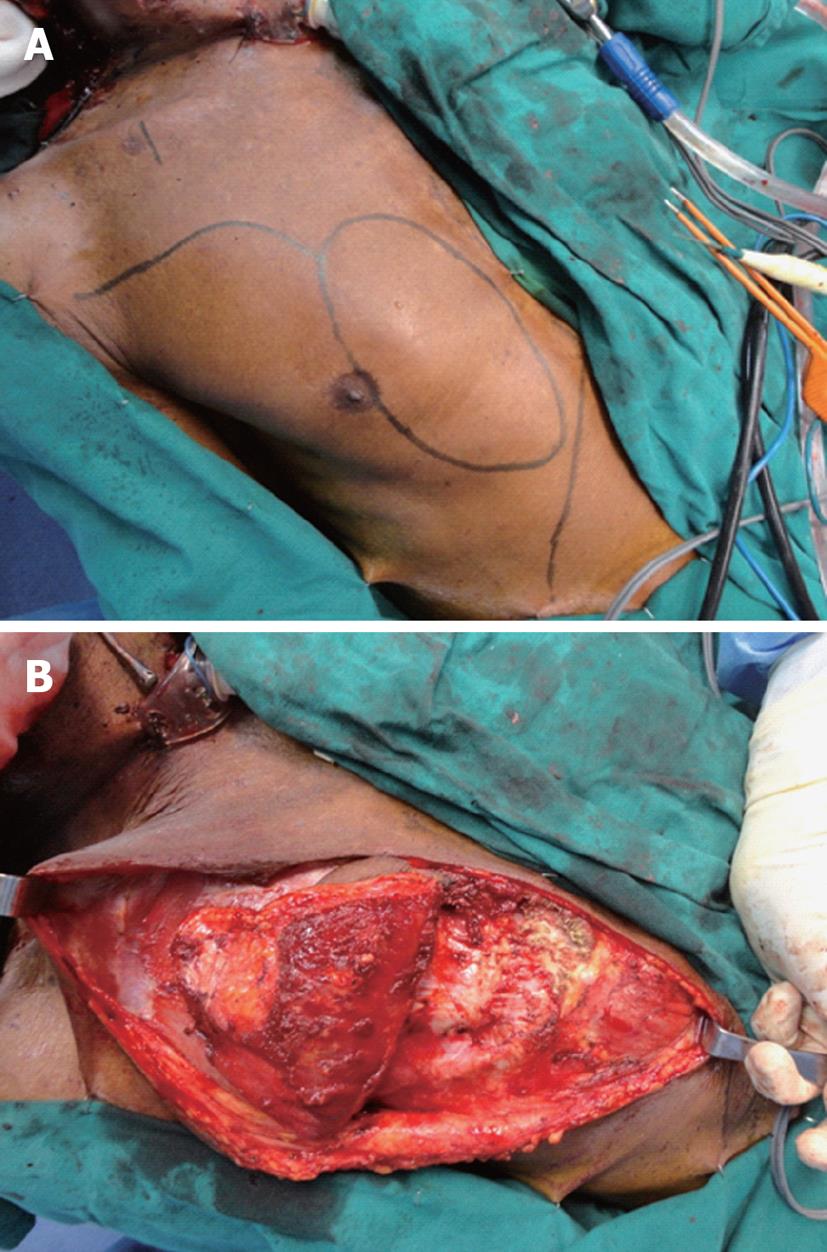

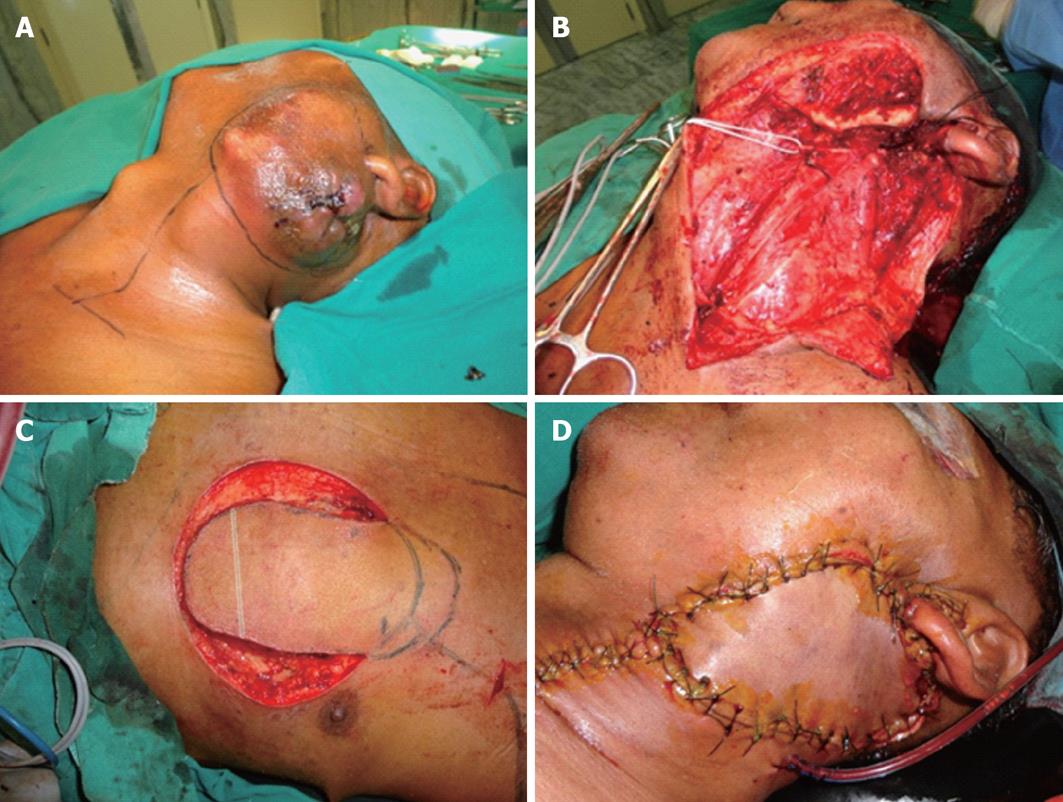

All cases of head and neck defects reconstructed by the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap at our tertiary referral center from 2010 to 2013 were retrospectively reviewed. Among these, cases of extended pectoralis major flap reconstructions were selected for analysis. For the purpose of this report, an extended flap was defined as the design and harvest of a skin paddle with the proximal portion overlying the pectoralis major muscle, and the distal portion extending beyond the inferior border of the muscle to include rectus sheath. The dimensions of the skin paddle were as closely matched as possible to that of the defect. The distal margin of the skin paddle was designed in a curvilinear manner to avoid a sharp tip. The pedicle length was designed so as to ensure an adequate arc of rotation (pivoted on the middle third of the clavicle) and sufficient tension free reach of the inferior margin of the skin paddle to the highest or most distal reach of the defect. A curvilinear line was drawn from the supero-lateral corner of the skin paddle to the anterior axillary fold (Figure 1). From this line an inferior flap was raised superficial to the pectoralis fascia to define the inferior border of pectoralis major muscle. This border was assessed in relation to the inferior border of the skin paddle. The portion of skin paddle extending beyond the inferior border of muscle was harvested with the corresponding underlying rectus sheath in a plane just superficial to rectus muscle. The cut margin of rectus sheath was sutured to the subcutaneous layer of the skin paddle to prevent shearing and disruption in blood supply during harvest. Further proximal harvest continued in a plane deep to pectoralis major muscle and superficial to pectoralis minor muscle. The vascular pedicle was identified on the deep surface of pectoralis major and protected during further harvest. If a second lateral pedicle (lateral thoracic artery) was present, it was divided to obtain adequate arc of rotation. Muscle around the vascular pedicle was thinned if necessary to facilitate distal reach of skin paddle. Pectoralis major muscle fibers were released from rib attachments and the humeral head was also detached completely. The flap was finally mobilized superiorly under the neck skin and the skin paddle was sutured to the defect margins in a single layer. Care was taken to ensure minimal tension and kinking of the vascular pedicle.

In the postoperative period, normal saline was infused at the rate of 100-120 cc/h for the first 24 h. Urinary output was monitored with the Foley catheter in-situ to ensure it remained above 50 cc/h. Packed red blood cell was transfused to maintain blood hemoglobin concentration at or above 9 g/dL. Oral or nasogastric tube feeding was commenced 24-48 h following surgery and gradually increased to approximately 3 L/d at which point intravenous fluids was completely stopped. The patient’s head was kept elevated by 45 degrees and maintained in a neutral position as far as possible. On the first postoperative day, the patient was made to sit in a chair and daily chest physiotherapy was commenced. Ambulation was started on the second postoperative day, and the Foley catheter was typically removed on the third day. In cases that required mucosal repair, nasogastric feeding and nil by mouth orders were continued until at least the 14th postoperative day and full healing of mucosal incision lines. Flap viability was checked on the first postoperative day by needle prick and then by visual inspection of skin color and turgor on a daily basis until discharge from hospital. Any loss of viability, such as skin necrosis, was recorded.

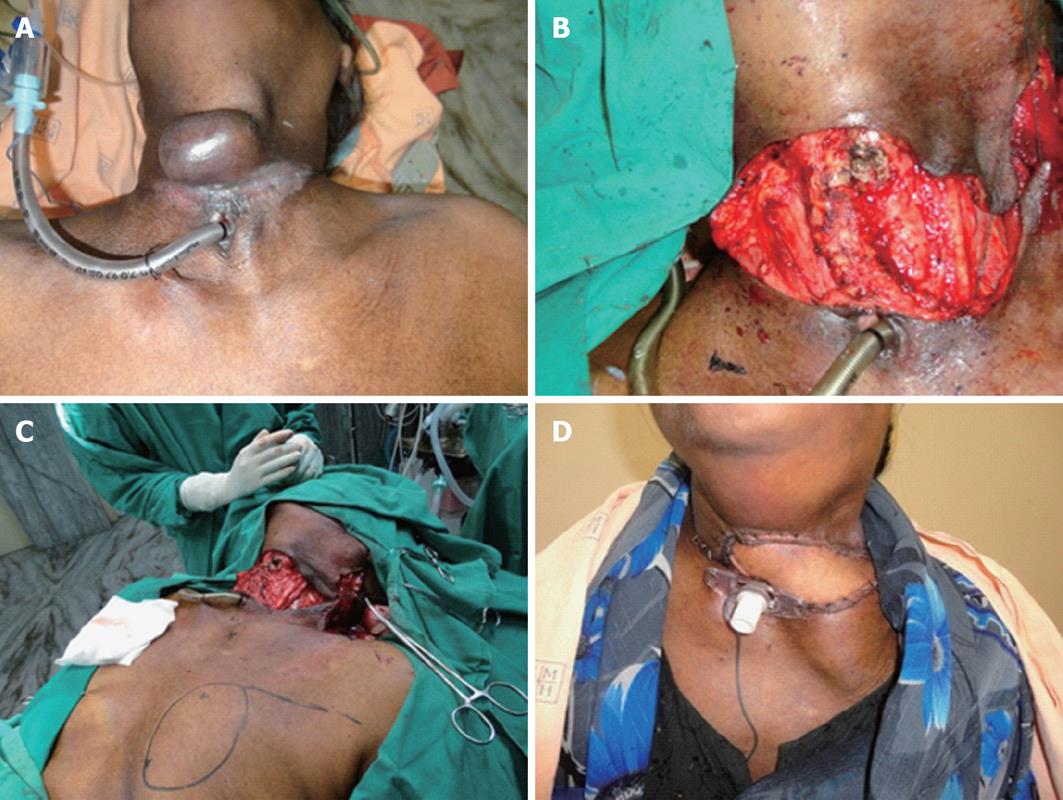

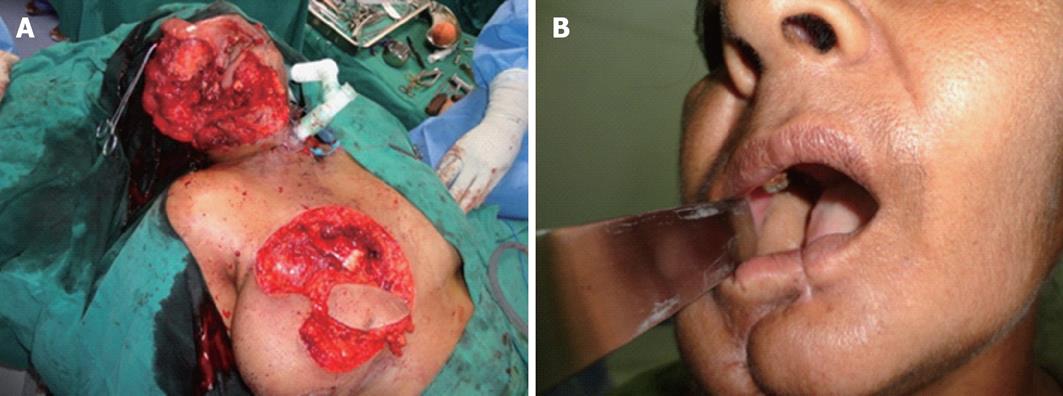

A total of 7 cases of extended pectoralis major myocutaneous flap repairs were done. Patient demographics are given in Table 1. No patient had received preoperative radiotherapy. The distal tip of the skin paddle extended beyond the lower border of pectoralis major by 2-5 cm. In all cases, this cut distal margin was confirmed to exhibit brisk bleeding during harvest. The indications for the extended flap were large defects of mucosal and/or skin surface, high defects involving soft palate or extending up to and beyond the temporal line, and complex, multi-dimensional intraoral defects requiring tension-free circumferential closure. Patients 3 and 7 had full thickness defects of the cheek with loss of skin, buccal soft tissue and mucosa. In the former patient, the surface area of the cutaneous defect was near-identical to that of the buccal defect (5 cm × 4 cm), while the cutaneous defect was much smaller (2 cm × 1 cm) in the latter. The skin paddle of the flap was used to resurface the cutaneous defect in the former and the buccal defect in the latter. The corresponding large buccal and small external cutaneous defects were reconstructed with split skin grafts. The donor site was closed primarily in 6 cases and a local rotation flap was required in 1 case. No patient required a second simultaneous flap for reconstruction (Figures 2-5).

| Pt No. | Age (yr)/sex | Primary tumor | Defect nature | Approximate skin paddle dimension (cm) |

| 1 | 60/F | CA thyroid | Large cutaneous and soft tissue defect | 7 × 4 |

| 2 | 54/M | CA retromolar trigone | Composite defect of oral mucosa and mandible | 6 × 3 |

| 3 | 45/F | CA buccal mucosa | Large full thickness composite defect cheek | 5 × 4 |

| 4 | 56/F | CA alveolus | Composite defect of oral mucosa and mandible | 6 × 4 |

| 5 | 66/M | CA retromolar trigone | Composite defect of oral mucosa and mandible | 6 × 4 |

| 6 | 55/M | CA parotid | Large cutaneous defect of cheek reaching temporal line | 8 × 6 |

| 7 | 50/F | CA alveolus | Large full thickness composite defect cheek | 8 × 4 |

One patient developed a seroma in the neck anterior to the flap muscle that settled on repeated aspiration. Two other patients developed orocutaneous fistula that healed by daily dressing. All flaps survived fully with no loss of skin viability or necrosis over a minimum follow-up of 60 d. Similarly, there was no major donor site complication.

The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap offers a very important reconstructive option in contemporary head and neck surgery. However, limiting the skin paddle to within the surface area of the pectoralis major muscle may occasionally restrict the ability to reconstruct large, high or complex defects. In this report, extension of the skin paddle inferiorly beyond the pectoralis major muscle has been shown not to compromise blood supply and this extended and robust skin paddle can be utilized to reliably reconstruct large or high defects.

The main blood supply to the pectoralis major is the thoracoacromial artery. There are two other vessels supplying the muscle: internal mammary artery with its perforating branches and lateral thoracic artery. The internal mammary vessels continue into the rectus sheath as the superior epigastric artery and vein with large perforators in the periumbilical region of the abdomen. The cutaneous vascular territories of these three vascular systems overlap to supply the skin of the anterior chest and upper abdomen[4]. Cadaveric dye injection studies have confirmed overlap of the skin territories of perforators from the internal mammary, superior epigastric and thoracoacromial systems over the sternum and upper abdominal wall[4,5]. It has been shown that in some cases, the skin paddle of the traditional pectoralis major flap can have a limited supply by the thoracoacromial artery, with the remaining area borne by the perforating branches of the internal mammary artery[6,7]. Extending the skin paddle inferiorly to include the rectus sheath as done in this report can capture the rich fascial vascular plexus of the lower chest and anterior abdominal wall. The distal skin must be designed in a curvilinear fashion to avoid a sharp tip and include the fascia covering the anterior abdominal wall to maintain the fascial vascular plexus. Proximally, the skin island must be designed to overlie the pectoralis muscle to allow the thoracoacromial perforating vessels access into the distal fascial plexus. The edges of the rectus sheath and superficial layers of pectoralis muscle must be sutured to the corresponding subcutaneous layer of the skin paddle to prevent shearing and loss of blood supply. Further harvest must be done gently, avoiding tension or torsion of the pedicle. Similarly, when muscle around the pedicle needs to be thinned, care must be taken to avoid thermal or crush injury to the pedicle. Provided these principles are strictly adhered to, we believe an inferiorly extended skin paddle can be safely harvested, avoiding previously reported complications with the pectoralis major flap[8-10]. Further, the distance between the lower skin margin and the inferior border of the pectoralis major muscle has been limited to 5 cm or less in this report. Future studies may assess whether further extension of the skin paddle inferiorly is feasible.

The indications for the extended flap in this report were large defects of mucosal and/or skin surface, high defects involving soft palate or extending up to and beyond the temporal line, and complex, multi-dimensional intraoral defects requiring tension-free circumferential closure. In our assessment, the traditional pectoralis major flap would have been insufficient for tension-free resurfacing of these defects. Even though a few flaps in this series had a relatively smaller skin paddle size, the extended flap conferred the advantage of superior reach, rotation and contouring for high and complex defects. We believe the extended flap overcomes several of the limitations imposed by the traditional pectoralis major flap by conferring a larger skin paddle for big defects and superior reach for high defects, thereby minimizing tension and overall compromise of blood supply to the flap. It is plausible that some of the complications reported previously with the pectoralis major flap[8,9] might have been avoided by utilizing the extended flap. Done in an appropriate manner as outlined here, the extended flap increases the versatility of pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction.

Post-ablative head and neck defects that involve large surface areas of the skin and/or mucosa, or extend high to involve the soft palate or up to and beyond the temporal line, are challenging to reconstruct. In this report, the extended pectoralis major myocutaneous flap has been shown to be ideal for repairing these large and complex defects. Further larger studies are required to confirm and expand our findings.

P- Reviewers Ciuman R, Deganello A, Gavriel H, Kuvat S S- Editor Qi Y L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Hueston JT, McConchie IH. A compound pectoral flap. Aust N Z J Surg. 1968;38:61-63. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ariyan S. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. A versatile flap for reconstruction in the head and neck. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Baek SM, Biller HF, Krespi YP, Lawson W. The pectoralis major myocutaneous island flap for reconstruction of the head and neck. Head Neck Surg. 1979;1:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Russell RC, Feller AM, Elliott LF, Kucan JO, Zook EG. The extended pectoralis major myocutaneous flap: uses and indications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:814-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McGregor IA, Morgan G. Axial and random pattern flaps. Br J Plast Surg. 1973;26:202-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang D, Marshall G, Morris SF. Variability in the vascularity of the pectoralis major muscle. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32:12-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schmelzle R. [Significance of the arterial supply for the formation of the pectoralis major island flap]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 1983;15:109-112. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Shah JP, Haribhakti V, Loree TR, Sutaria P. Complications of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction. Am J Surg. 1990;160:352-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mehrhof AI, Rosenstock A, Neifeld JP, Merritt WH, Theogaraj SD, Cohen IK. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction. Analysis of complications. Am J Surg. 1983;146:478-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ramakrishnan VR, Yao W, Campana JP. Improved skin paddle survival in pectoralis major myocutaneous flap reconstruction of head and neck defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |