Published online Nov 29, 2024. doi: 10.5319/wjo.v11.i3.33

Revised: July 30, 2024

Accepted: October 30, 2024

Published online: November 29, 2024

Processing time: 173 Days and 16.5 Hours

A 48-year-old female presented with sudden-onset right-sided aural fullness, low-frequency hearing loss, and tinnitus. Medical history included right-sided tempo

The patient sought physical therapy for TMJD; testing revealed reduced motion and dysfunction with vertical opening, lateral excursion of the mandible to the right, and tenderness to palpation. Treatment included soft tissue mobilization of right facial structures and temporal fossa, intraoral massage of the right pterygoid musculature, and massage of right neck structures. After 4 weeks, the patient noticed subjective improvement in hearing and decreased headaches. After 11 weeks, an audiogram showed that the hearing loss had recovered. The patient has continued the daily at-home intraoral/neck massage therapy and maintained normal hearing over 4 years to date. The temporal relationship between physical therapy and recovery of hearing loss suggests muscular or inflammatory etiology as at least partially causative of this patient’s symptoms. The mechanism of healing may have been due to decreased inflammation, improved blood flow, restored function of cranial nerves, or some combination of these and other unknown factors.

This report suggests that orofacial physical and massage therapy may be an effective treatment for the cochlear symptoms associated with MD.

Core Tip: A patient who experienced right-sided symptoms of Meniere’s disease (MD) with comorbid right sided temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJD) and mid-face/retro-orbital headaches experienced no relief from traditional MD treatments. The patient sought out physical therapy for TMJD, which included soft tissue mobilization of right facial structures and temporal fossa, intraoral massage, and massage of right neck structures. The patient recovered from the right-sided hearing loss and associated MD symptoms and had decreased headaches after 1 month. Physical and massage therapy for the cochlear symptoms associated with MD may be an important adjunctive treatment, though confirmatory studies are needed.

- Citation: Pillsbury K, Helm B, Kuhn JJ. Recovery of hearing loss in atypical Meniere’s disease after treatment with orofacial and neck massage: A case report. World J Otorhinolaryngol 2024; 11(3): 33-40

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6247/full/v11/i3/33.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5319/wjo.v11.i3.33

The underlying etiology of Meniere’s disease (MD) is not fully understood[1], with a variable clinical presentation that includes spinning vertigo with tinnitus, fluctuating hearing, and/or fullness of the ear. Current medical treatment recommendations include diuretics, a low-sodium diet, and intratympanic steroid therapy[2], but outcomes are unpredictable and there is no cure.

The following is a report of a patient diagnosed with atypical MD (cochlear symptoms and periodic disequilibrium without spinning vertigo) who showed no improvement over one year while receiving conventional recommended therapeutics. However, the patient rapidly improved and recovered full hearing with reduction of aural fullness and tinnitus after receiving physical therapy of the neck, face, and jaw (including intraoral massage) over an 11-week interval.

A 48-year-old female presented with sudden-onset right-sided ear fullness, tinnitus, and sound distortion. The patient denied having spinning vertigo, but had experienced periodic brief episodes of disequilibrium.

The patient had no history of present illness.

The patient had no history of past illness.

The patient’s medical history included panic disorder, right-sided temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJD) with crepitation, and infrequent mild-to-moderate mid-face/retro-orbital headaches. There were no other comorbidities, and the patient did not use alcohol or tobacco. Current medications were venlafaxine 18.75 mg daily and alprazolam 0.25 mg as needed for management of panic attacks. The patient noted that the aural symptoms began after a recent emotionally traumatic event. She initially presented to her primary care physician who prescribed Flonase and referred her to an otolaryngologist.

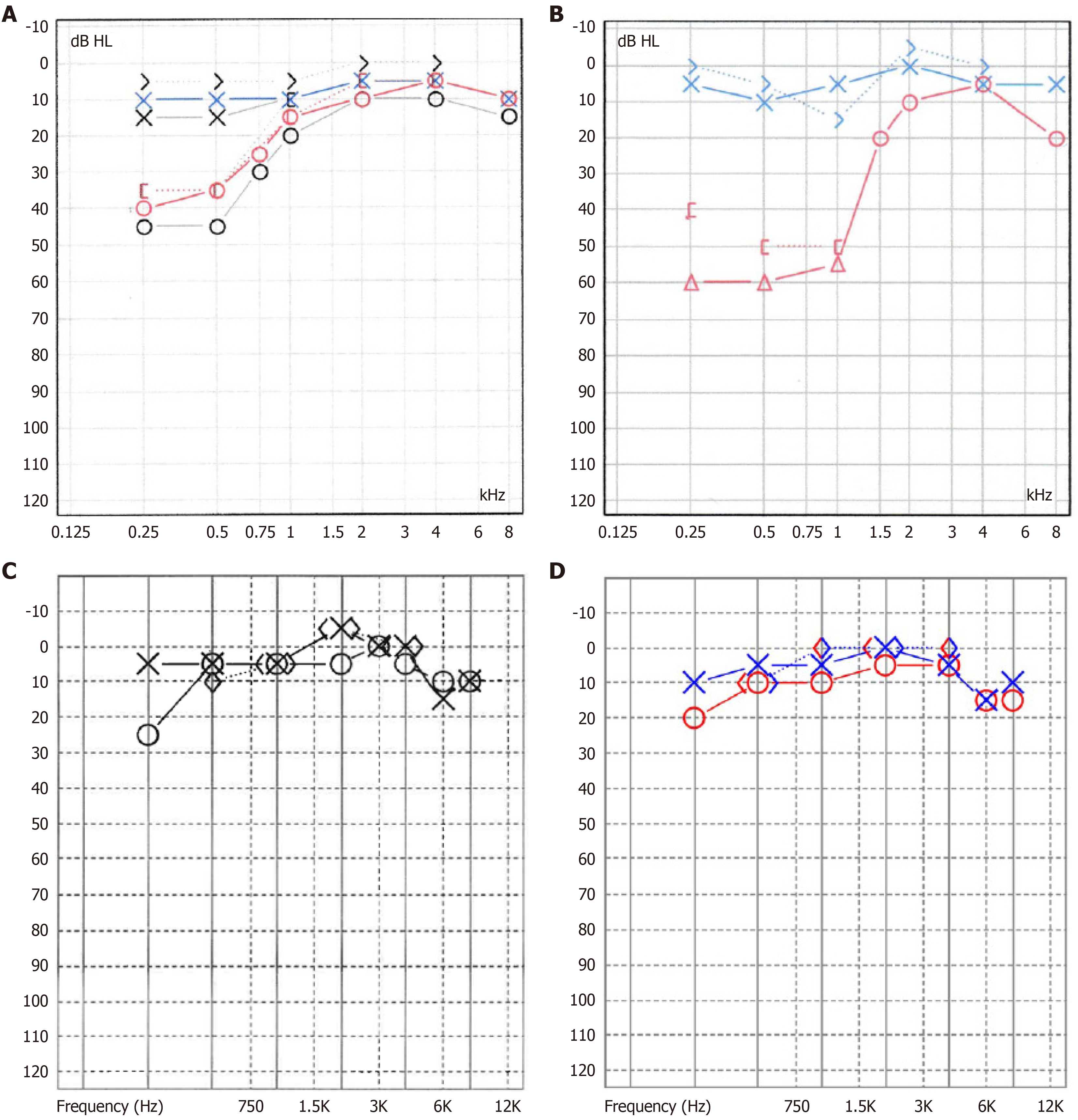

Her head and neck examination, including otologic and cranial nerve examination, was unremarkable. Pure tone audiometry showed a right-sided low-frequency hearing loss (Figure 1A) with normal hearing in the left ear, and word recognition scores of 92% in the right ear and 100% in the left. Tympanometry showed bilateral type A configuration. The patient was initially diagnosed with low-frequency sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL) and cochlear hydrops.

Electrocochleography showed normal results for both ears. She was referred to a neurotologist and treated with a tapering course of oral prednisone with no improvement in symptoms or recovery of right-sided hearing loss.

An autoimmune inner ear disease test (heat shock protein 70, immunoglobulin G antibodies) was negative.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the internal auditory canals and cerebellopontine angle was unremarkable.

The patient was diagnosed with atypical MD, as the symptom complex and hearing loss configuration met all criteria for MD except for spinning vertigo[2] though the hearing loss and aural symptoms were constant and not episodic.

The patient received intratympanic steroid therapy, started a low-sodium diet (less than 1800 mg sodium/day), and began taking betahistine 16 mg per day. After several months, the patient’s right-sided hearing loss worsened despite treatment (Figure 1B).

The patient then tried several alternative therapy regimens including several weeks of oral valacyclovir, the John of Ohio supplement regimen for MD, acupuncture, and various splints to treat the pre-existing history of TMJD. Her aural symptoms and hearing loss did not improve in response to any of these alternative therapies, and after 9 months she abandoned these therapies and diets, although she continued to take betahistine daily. Right-sided ear symptoms and hearing loss failed to improve and did not worsen after discontinuation of these treatments.

One year following the initial diagnosis, the patient was placed on a trial of gabapentin 100 mg BID, but treatment was discontinued due to excessive daytime drowsiness even at much lower doses (25 mg every night at bedtime).

The patient then sought out physical and massage therapy for TMJD and aural symptoms. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the mandible showed flattening of the super anterior condylar surface on the right side with volume loss of the superior aspect of the condylar head and an osseous projection at the anterior surface of the condyle. The condylar eminence was flattened and congruent with the temporomandibular fossa. The left side temporomandibular joint (TMJ) showed normal anatomy and cortication.

The physical therapist noted decreased static/dynamic functional balance, diminished ambulatory balance (functional gait assessment = 20/30 points) and dizziness with activities of daily living (dizziness handicap inventory = 50/100 points). TMJ testing revealed reduced motion and dysfunction with vertical opening, lateral excursion of the mandible to the right, and protrusion. The physical therapist noted that the patient was tender to palpation throughout the cervical and craniofacial regions. The patient demonstrated pain and reduced active range of motion with cervical rotation and upper cervical flexion and bilateral rotation. She reported symptoms of dizziness during saccades, head thrust to the right, and gaze stabilization activities.

The treatment plan included soft tissue mobilization of right facial structures (particularly the masseter) and right temporal fossa, intraoral massage of the right pterygoid musculature, and massage of right neck structures including the sternocleidomastoid muscle and scalene musculature from the occipital and retromandibular region to the level of the clavicle. Treatment was performed in-clinic weekly for a total of 11 visits, and a concurrent home therapy regimen of daily intraoral and neck massage. Clinical intervention and the home exercise program included strengthening of postural stability muscles to improve postural alignment during function. The treatment program also consisted of stretching exercises for sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius and levator scapulae to address mobility dysfunction with cervical rotation and side-bending. The patient was educated in a program for intraoral release for the right TMJ region to address dysfunctional movement patterns. The patient was also instructed to perform controlled opening activity of the lower jaw with mirror feedback to emphasize neutral positioning during opening and closing motion. In addition, the patient performed a dynamic balance program and gaze stabilization activities to facilitate improved function of the vestibular system.

After the first 4 weeks, the patient noticed subjective improvement in right-sided hearing and a decrease in the intensity of right aural fullness and tinnitus. A phone-based audiogram app showed some improvement in the right low-frequency hearing loss. Headaches were also less frequent and less intense. Physical and massage therapy continued for another 7 weeks with further subjective improvement of all symptoms. A follow-up audiogram showed significant improvement in the right low-frequency hearing loss (Figure 1C) to near-normal levels, with word recognition at 100% for both ears.

The patient continued the daily at-home intraoral and neck massage therapy and has maintained normal hearing in the right ear over 4 years to date. A recent audiogram showed normal hearing in all frequencies (Figure 1D). The patient has not taken or pursued any other therapies outside of daily betahistine (16 mg/day) and the at-home physical and massage therapy program. The only residual symptom of atypical MD is mild right-sided tinnitus which is exacerbated by emotional stress or caffeine consumption.

This patient’s unexpected recovery from acute low-frequency hearing loss, aural fullness, and tinnitus after receiving physical therapy may be attributable to a number of factors, however the temporal relationship between receiving physical therapy on the neck, face and jaw and the rapid resolution of symptoms suggests a muscular, inflammatory, and/or TMJD etiology as at least partially causative. The physical therapy treatment was initiated for the improvement of the muscular and inflammatory issues associated with the patient’s right-sided TMJD, and produced a parallel rapid improvement and ultimate resolution of the patient’s right-sided low-frequency hearing loss, aural fullness, and a decrease in tinnitus intensity.

The surmised link between TMJD and otologic symptoms is not new, and has been explored in prior research. Given the anatomical proximity between the TMJ, the muscles innervated by the trigeminal nerve, and structures of the ear[3,4], otologic symptoms (particularly aural fullness and tinnitus) are common in patients with TMJD, with prevalence estimates as high as 87%[3]. Research has also shown increased prevalence of TMJD in patients with MD compared to healthy controls[5]. Pekkan et al[6] reported that TMJD patients with otological complaints tend to have hearing impairment at low frequencies, and Kitsoulis et al[7] reported that moderate and severe TMJD was associated with hearing loss of median and low tones.

The patient in this report had both TMJD and MD. There are several theories as to how TMJD can produce similar and overlapping otologic symptoms as seen in MD. It has been hypothesized that TMJD can influence activation of the auriculotemporal nerves[3] or alter inner ear pressure equilibrium[8]. Alternatively, pain from TMJD can be caused, in part, by the pathological contraction of the masticatory muscles which can stimulate an extravascular inflammatory process and potentially aural fullness[7,9]. Neurogenic inflammation (including release of pro-inflammatory factors) can be caused by injury to the TMJ[10,11], thus sensitizing the trigeminal and facial nerves, leading to vasospasm or tonic spasm of middle ear muscles[7]. It has been theorized that altered trigeminal nerve input caused by TMJ dysfunction may cause activity changes in the dorsal cochlear nucleus that might affect the central auditory pathway, with resulting otologic symptoms[12].

The collective innervation (and irritation) of the tensor tympani, tensor veli palatini, tympanic membrane, and masseter, temporalis, and pterygoid muscles by way of the trigeminal nerve, or the potential contraction of the blood vessels supplying the cochlea, or bruxism leading to microtraumas, can all be contributors to otologic symptoms[13,14]. At the time of the abrupt hearing loss, the patient in this report had moderate-to-severe TMJD (on the same side), as evidenced by CT imaging showing a flattened condyle and signs of joint degeneration, in addition to the patient’s symptoms of morning headache, crepitus, and deviation of the mandible to the affected side upon opening. The combination of moderate-to-severe right-sided TMJD may have been a contributing factor to the symptoms of atypical MD, given that her symptoms resolved with TMJD-focused physical therapy that included massage and soft tissue mobilization of the jaw, face, and neck.

While the TMJD causation model seems biologically plausible, central mechanisms could also be contributory or overlapping with TMJD and MD in this patient and others; specifically, this patient could also be afflicted with cochlear migraine. Migraine is associated with inner ear pathologies, including vertigo and tinnitus[15]. Two types of migraine with inner ear symptoms–vestibular migraine and cochlear migraine–have been proposed as distinct entities; vestibular migraine includes migraine with vertigo symptoms, and cochlear migraine includes migraine and auditory symptoms. It has been theorized that MD and migraine inner ear disorder may instead exist on a spectrum, with some patients having only vestibular symptoms (e.g., vertigo, motion sensitivity), termed vestibular migraine on one end, and patients who have only cochlear symptoms (e.g., fluctuating hearing loss, aural pressure, tinnitus) on the other[15]. When experienced together, they form a symptom complex termed cochleovestibular migraine that is similar in presentation to MD[15]. In fact, patients with vestibular migraine are sometimes misdiagnosed as having MD[16]. Of note, it has been hypothesized that migraine and MD share a common etiology[11]. Past research has shown that up to 51% of individuals with MD experience migraine compared to 12% in the general population[15].

According to the diagnostic criteria newly proposed by Lai and Lui[17] in 2018, the patient in this report would meet the criteria for cochlear migraine, though the diagnosis of cochlear migraine is largely still a theoretical concept. While the overlap between vestibular migraine and MD has been well-described, there are limited data published in reports on cochlear migraine. Hwang et al[18] conducted one large population-based study in Taiwan, and found that the incidence of cochlear disorders (defined as tinnitus, sensorineural hearing loss, and/or SSHL) was found to be significantly higher among patients with a history of migraines, providing some population-based evidence that migraine can impact the auditory system[19].

A widely accepted model of migraine revolves around the trigeminovascular system[11]. Similar to the TMJD model of otologic symptoms, it is thought that innervation and sensitization of the cochlea and cochlear blood vessels by the trigeminal nerve contribute to the vascular effects of migraine and may impact the inner ear[15,16,20], and that the cochlea is susceptible to injury from vascular dysfunction[21]. It has been shown that the trigeminal nerve directly affects blood flow to the inner ear through innervation of cochlear vasculature[11]. It is possible that the trigeminovascular system in migraine patients causes perfusion deficits in the inner ear; e.g., involvement of the spiral modiolar artery leading to the historically described “cochlear” MD with low-frequency hearing loss[11], similar to the patient described in this report. Reduction in blood flow to the cochlea due to vasospasms would affect the apical turn of the cochlea and has been proposed to describe why the hearing loss is in the low frequencies[16,22].

Multiple studies have found an association between stress levels and migraine occurrence; similarly, physiologic stressors can also provoke MD symptoms[15] potentially via activation of afferent pathways through the trigeminal nerve. Given that the patient in this report experienced hearing loss abruptly in the morning after an emotionally traumatic event, it is plausible that this traumatizing event and subsequent physiologic stress changed and compromised the functional dynamics of the inner ear. It is also possible that intense emotional stress stimuli caused an increase in TMJD behaviors in the patient (bruxing or clenching) and led to the symptoms associated with MD. Alternatively, an overlap of factors between processes related to both TMJD and central processes occurred. For example, it has been shown that patients with TMJD have greater electromyographic activity in the neck and trunk, potentially sensitizing the autonomic nervous system and potentially leading to migraine via the trigeminal nerve[7]. Taken together, an overlap of symptoms may exist amongst TMJD, MD, and migraine[18,23-26] and all 3 disorders can be exacerbated by emotional and psychological stress.

For the patient in this report, it appears that with enough stressors (whether mechanical, muscular, vascular constriction, or central biochemical processes) the patient’s right ear showed the symptoms of cochlear hydrops and was resistant to conventional medication, unconventional medications, and dietary protocols. The mechanism of healing from the physical therapy intervention may have been based in reduction of inflammation, increased blood flow to injured tissues or muscles, restored function of cranial nerves, or some combination of these and possibly other unknown factors. Past research has reported that myofascial treatments have been shown to alleviate certain types of tinnitus[27,28] and the symptom of aural fullness related to TMJD[9,29], but there are very limited data reported to show that physical therapy can improve the cochlear symptoms in MD. This report suggests that physical and massage therapy of the face, jaw, and neck may be an effective treatment for the cochlear symptoms associated with MD, and merits further study.

It's important to consider that this patient’s rapid recovery after receiving physical therapy may be attributable to another cause, such as spontaneous recovery that occurred simultaneously to receiving physical therapy, the fluctuating nature of MD, or due to the use of betahistine. Though the patient had been taking betahistine for several months prior to receiving physical therapy without improvement, the use of this daily medication could be a potential confounder in this patient’s recovery. Additionally, the patient may have been misdiagnosed with atypical MD but instead has one of the atypical variants of migraine.

The complementary treatment of the cochlear symptoms of MD by a physical therapist may be beneficial for patients. Although physical therapy has been shown to be effective for vestibular disorders, less is known regarding efficacy for cochlear symptoms and disorders. Integrating physical therapy treatment may be particularly effective for patients with cochlear disorders who have comorbid TMJD or migraine, as choosing therapeutic options that target both auditory and musculoskeletal symptoms can potentially yield improved outcomes. Given that the pathophysiology associated with MD is unknown, and that current conventional treatments are limited and have unpredictable outcomes, physical and massage therapy for the cochlear symptoms associated with MD may prove to be an important adjunctive treatment, though confirmatory studies are needed.

For clinical advisement and support, we would like to thank Pillsbury D, (retired) Director of the Audiology and Speech Pathology Department at Wake Forest Baptist Hospital. Further thanks to Lamb K, for medical advice and support.

| 1. | Oberman BS, Patel VA, Cureoglu S, Isildak H. The aetiopathologies of Ménière's disease: a contemporary review. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2017;37:250-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Basura GJ, Adams ME, Monfared A, Schwartz SR, Antonelli PJ, Burkard R, Bush ML, Bykowski J, Colandrea M, Derebery J, Kelly EA, Kerber KA, Koopman CF, Kuch AA, Marcolini E, McKinnon BJ, Ruckenstein MJ, Valenzuela CV, Vosooney A, Walsh SA, Nnacheta LC, Dhepyasuwan N, Buchanan EM. Clinical Practice Guideline: Ménière's Disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162:S1-S55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kusdra PM, Stechman-Neto J, Leão BLC, Martins PFA, Lacerda ABM, Zeigelboim BS. Relationship between Otological Symptoms and TMD. Int Tinnitus J. 2018;22:30-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Porto De Toledo I, Stefani FM, Porporatti AL, Mezzomo LA, Peres MA, Flores-Mir C, De Luca Canto G. Prevalence of otologic signs and symptoms in adult patients with temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bjorne A, and Agerberg G. Craniomandibular disorders in patients with Meniere's disease: a controlled study. J Orofac Pain. 1996;10:28-37. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pekkan G, Aksoy S, Hekimoglu C, Oghan F. Comparative audiometric evaluation of temporomandibular disorder patients with otological symptoms. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2010;38:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kitsoulis P, Marini A, Iliou K, Galani V, Zimpis A, Kanavaros P, Paraskevas G. Signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorders related to the degree of mouth opening and hearing loss. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2011;11:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Effat KG. Otological symptoms and audiometric findings in patients with temporomandibular disorders: Costen's syndrome revisited. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:1137-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Peng Y. Temporomandibular Joint Disorders as a Cause of Aural Fullness. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;10:236-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Franz B, Anderson C. The potential role of joint injury and eustachian tube dysfunction in the genesis of secondary Ménière's disease. Int Tinnitus J. 2007;13:132-137. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Liu YF, Xu H. The Intimate Relationship between Vestibular Migraine and Meniere Disease: A Review of Pathogenesis and Presentation. Behav Neurol. 2016;2016:3182735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee CF, Lin MC, Lin HT, Lin CL, Wang TC, Kao CH. Increased risk of tinnitus in patients with temporomandibular disorder: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:203-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maciejewska-Szaniec Z, Maciejewska B, Mehr K, Piotrowski P, Michalak M, Wiskirska-Woźnica B, Klatkiewicz T, Czajka-Jakubowska A. Incidence of Otologic Symptoms and Evaluation of the Organ of Hearing in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders (TDM). Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:5123-5129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ramirez Aristeguieta LM, Ballesteros Acuña LE, Sandoval Ortiz GP. [Tensor veli palatini and tensor tympani muscles: anatomical, functional and symptomatic links]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2010;61:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sarna B, Abouzari M, Lin HW, Djalilian HR. A hypothetical proposal for association between migraine and Meniere's disease. Med Hypotheses. 2020;134:109430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ghavami Y, Mahboubi H, Yau AY, Maducdoc M, Djalilian HR. Migraine features in patients with Meniere's disease. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lai JT, Liu TC. Proposal for a New Diagnosis for Cochlear Migraine. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:185-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hwang JH, Tsai SJ, Liu TC, Chen YC, Lai JT. Association of Tinnitus and Other Cochlear Disorders With a History of Migraines. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:712-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lin HW, Djalilian HR. The Role of Migraine in Hearing and Balance Symptoms. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:717-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vass Z, Shore SE, Nuttall AL, Miller JM. Direct evidence of trigeminal innervation of the cochlear blood vessels. Neuroscience. 1998;84:559-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mohammadi M, Taziki Balajelini MH, Rajabi A. Migraine and risk of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5:1089-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mom T, Chazal J, Gabrillargues J, Gilain L, and Avan P. Cochlear blood supply: an update on anatomy and function. Fr ORL. 2005;88:81-88. |

| 23. | Arslan Y, Arslan İB, Aydin H, Yağiz Ö, Tokuçoğlu F, Çukurova İ. The Etiological Relationship Between Migraine and Sudden Hearing Loss. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:1411-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Omidvar S, Jafari Z. Association Between Tinnitus and Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2019;128:662-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Teixido M, Seymour P, Kung B, Lazar S, Sabra O. Otalgia associated with migraine. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32:322-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bjorne A, Agerberg G. Symptom relief after treatment of temporomandibular and cervical spine disorders in patients with Meniere's disease: a three-year follow-up. Cranio. 2003;21:50-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sanchez TG, Rocha CB. Diagnosis and management of somatosensory tinnitus: review article. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:1089-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tuz HH, Onder EM, Kisnisci RS. Prevalence of otologic complaints in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:620-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dalla-Bona D, Shackleton T, Clark G, Ram S. Unilateral ear fullness and temporary hearing loss diagnosed and successfully managed as a temporomandibular disorder: a case report. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:192-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |