Published online Nov 12, 2013. doi: 10.5318/wjo.v3.i4.38

Revised: November 1, 2013

Accepted: November 5, 2013

Published online: November 12, 2013

Processing time: 69 Days and 2.5 Hours

Human infection of Toxocara canis in eye is usually an outcome of accidental ingestion of the embryonated eggs. The average age at diagnosis of ocular Toxocariasis is 7.5 years, ranging from 2 to 31 years. It constitutes 1%-2% of uveitis in children. Diagnosis is based upon the clinical features observed in a young patient and confirmed by the presence of specific IgG in the serum or aqueous humor by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test. We report a case of Presumed Toxocara infection in 45-year-old male which is unique in presentation with multifocal granulomata in retina. Our PubMed search could not produce case with similar presentation. Probably this is the first reported case of multifocal granulomata in presumed ocular Toxocara in any age group

Core tip: Toxocara infection is one of the causes of posterior uveitis. Diagnosis is often made by presence of larvae in the choroidal granuloma. The aim of this study is to focus on the diagnosis of case where presence of multifocal granuloma and absence of larvae in granulaoma makes the diagnosis atypical. A combination of history, clinical examination, laboratory tests and histopathological analysis is important before reaching any diagnosis.

- Citation: Kuniyal L, Biswas J. Multifocal granulomata in presumed Toxocara canis infection in adult. World J Ophthalmol 2013; 3(4): 38-40

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6239/full/v3/i4/38.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5318/wjo.v3.i4.38

The larva of the nematode Toxocara canis was first identified as a cause of intraocular disease by Nichols (1956). Human infection is usually an outcome of accidental ingestion of the embryonated eggs[1]. The average age at diagnosis of ocular Toxocariasis is 7.5 years (ranging from 2 to 31 years). It constitutes about 1%-2% of uveitis in children[2]. Toxocara should be considered as a possible causative agent of posterior uveitis. Diagnosis is based upon clinical features observed in a young patient and should be confirmed at least by the presence of specific IgG in the serum (ELISA test, 90% specificity and 91% sensitivity)[3]. We present here presumed ocular Toxocara infection in a 45 year adult. The case is unique for its presentation at this age and multifocal granulomata on retinal evaluation. PubMed search could not reveal presence of multifocal granulomata in ocular Toxocara infection before.

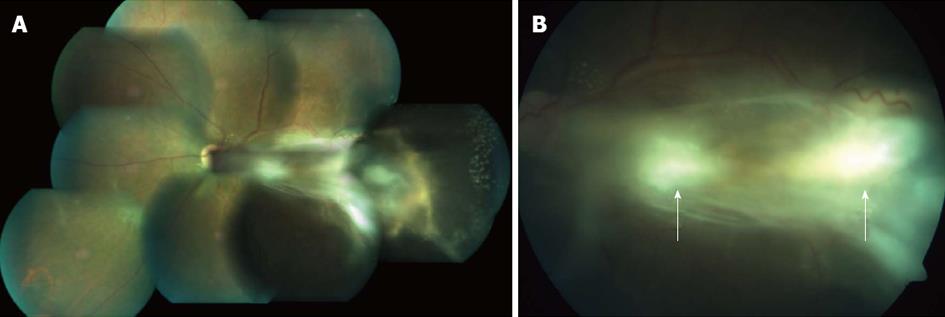

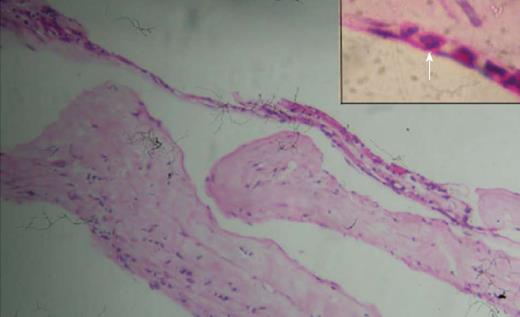

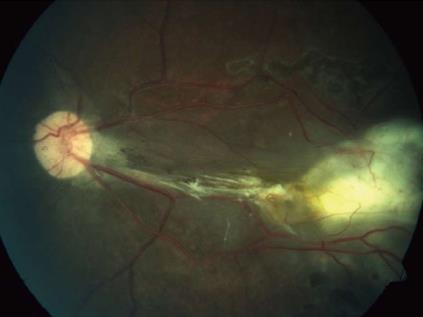

A 45-year-old male presented with complaints of gradually progressive diminution of vision since one and half years in the left eye. There were no pets in the house. Patient was a known diabetic controlled on oral hypoglycemic agents. At presentation his corrected visual acuity in right eye was 6/5 for distance with near vision N6 and left eye had counting finger for distance with near vision < N36 on snellens chart. Anterior segment findings were within normal limits. Right eye fundus was within normal limits whereas left eye fundus showed fibrous membranous band extending from optic nerve head to temporal periphery with subretinal exudation and exudative retinal detachment temporally (Figure 1). The unique thing about this lesion was that it covered area from posterior pole to far temporal periphery and showed multifocal choroidal granulomata which are very unusual of Toxocara granuloma (Figure 1). Investigation revealed positive IgE titer of Toxocara in anterior chamber tap (16.93NTU). Optical coherence tomography showed macular traction with increased retinal thickness. Patient was started on oral steroids and planned for surgery. Vitrectomy with membrane peeling was done. Silicone oil was injected when break occurred while removing adherent membrane. Histopathological analysis of the membrane showed fibrous tissue with chronic inflammatory cells. No Toxocara parasite was seen. On careful examination few eosinophils were seen (Figure 2). After 6 wk of surgery retina was attached with scarring extending from disc to temporal periphery. Patient had vision of counting finger which was due to scarring (Figure 3). Patient was doing well on ten weeks of follow up.

Ocular Toxocariasis usually occurs in young healthy children. It is usually limited to one eye and infected by one larva (Schlaegel, 1978)[4]. There are few clinical reports of retinal lesions in adults due to Toxocara infection. Larva is rarely identified from the lesions. Definitive histopathological diagnosis is possible only after enucleation. Because of the absence of larva on histopathology, we refer our case as Presumed Ocular Toxocariasis.

Ocular involvement can occur in form of chronic endophthalmitis, papillitis, posterior pole granuloma and peripheral granuloma[1]. Patients with posterior pole granuloma may initially present with relatively hazy vitreous body and sign of acute inflammation, in which the posterior pole granuloma is observed as an ill-defined hazy mass with surrounding vitreous inflammation. These lesions are usually very well-defined and relatively small, ranging from 0.75 to 6.0 mm in diameter in size. In peripheral granuloma, a dense white peripheral inflammatory granulomatous mass is localized. Alternatively, the inflammation may be diffuse and appears as a “snowbank ” as seen in pars planitis. Fibrocellular bands may run from a peripheral inflammatory mass to posterior retina or the optic nerve leading to both traction and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment[5].

Our patient presented with combined picture of posterior and peripheral granuloma with multifocal granulomata. The presence of multifocal granulomata in our patient was unusual and probably the first time reported.

The major causes of visual acuity loss are: severe vitritis (52.6% of the cases), cystoid macular edema (47.4%) and tractional retinal detachment (36.8%)[6]. It is possible that the lesions are due to a toxic or immunoallergic reaction towards larval antigens, mainly associated with larval death. The disruption occurring after larval death may determine an inflammatory reaction and granuloma formation. We also found the presence of chronic inflammatory cells along with eosinophils confirming the inflammatory nature of the membrane.

Treatment therapy should be guided according to: visual acuity, severity of inflammation, irreversible ocular damage[1]. Generally peripheral granulomata are silent or show minimal inflammatory reaction and do not require therapy. Corticosteroid therapy helps to reduce the inflammatory process without permitting the overgrowth of the infectious agent. Antihelminthic therapy is not worldwide accepted because of the possibility that larvae death may increase the inflammatory reaction. Pars plana vitrectomy is useful and indicated to remove vitreous opacities and epiretinal membranes, to relieve the vitreoretinal traction, to prevent and treat retinal detachment[7,8].

In our patient we successfully removed the membranes despite its firm adherence to underlying tissue. The vision was counting finger because of scarring over posterior pole caused by the membrane.

A study with longer follow up is required to see how multifocal granulomata differ in prognosis from usual focal granuloma of Toxocara.

A 45-year-old male presented with complaints of gradually progressive diminution of vision since one and half years in the left eye.

Right eye fundus was within normal limits whereas left eye fundus showed fibrous membranous band extending from optic nerve head to temporal periphery with subretinal exudation and exudative retinal detachment temporally.

Patient was started on oral steroids and planned for surgery. Vitrectomy with membrane peeling was done. Silicone oil was injected when break occurred while removing adherent membrane. Histopathological analysis of the membrane showed fibrous tissue with chronic inflammatory cells. No Toxocara parasite was seen.

Ocular Toxocariasis usually occurs in young healthy children. It is usually limited to one eye and infected by one larva (Schlaegel, 1978). There are few clinical reports of retinal lesions in adults due to Toxocara infection. Larva is rarely identified from the lesions.

This manuscript entitled “Multifocal Granulomata in Presumed Toxocara Canis Infection in Adult” to report a 45 years old case with fibrous membranous band extending from optic disc to temporal periphery with subretinal exudation and exudative retinal detachment temporally. A positive IgE titer of Toxocara was also found in AC tapping. This is an interesting paper and well written.

P- Reviewers: Jhanji V, Inan UU, Shih YF S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Pivetti-Pezzi P. Ocular toxocariasis. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6:129-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nussenblatt RB. Toxocara canis. B., Whitcup S, editors. Uveitis: Fundamentals and clinical practice. Philadelphia: Mosby 2004; 244-249. |

| 3. | de Visser L, Rothova A, de Boer JH, van Loon AM, Kerkhoff FT, Canninga-van Dijk MR, Weersink AY, de Groot-Mijnes JD. Diagnosis of ocular toxocariasis by establishing intraocular antibody production. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:369-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schlaegel TF Jr, Knox DL. Uveitis and Parasitosis. In: Duane TD, editor. Clinical Ophthalmology. 1987;4:10-14. |

| 5. | Park SP, Park I, Park HY, Lee SU, Huh S, Magnaval JF. Five cases of ocular toxocariasis confirmed by serology. Korean J Parasitol. 2000;38:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stewart JM, Cubillan LD, Cunningham ET. Prevalence, clinical features, and causes of vision loss among patients with ocular toxocariasis. Retina. 2005;25:1005-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Werner JC, Ross RD, Green WR, Watts JC. Pars plana vitrectomy and subretinal surgery for ocular toxocariasis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:532-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Amin HI, McDonald HR, Han DP, Jaffe GJ, Johnson MW, Lewis H, Lopez PF, Mieler WF, Neuwirth J, Sternberg P. Vitrectomy update for macular traction in ocular toxocariasis. Retina. 2000;20:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |