Published online Aug 10, 2016. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v5.i3.210

Peer-review started: March 27, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: May 10, 2016

Accepted: June 1, 2016

Article in press: June 3, 2016

Published online: August 10, 2016

Processing time: 138 Days and 0.6 Hours

AIM: To theorize that performing a laparoscopic Burch urethropexy at time of sling removal would significantly decrease subjective symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and improve patient satisfaction.

METHODS: Women who underwent a combined sling removal and laparoscopic Burch procedure between 2009 and 2014 were matched via age and sling-type in a 1:2 ratio to women who only underwent a sling removal. Those who underwent surgery within 6 mo of data collection were excluded from the study, as were women who underwent multi-stage surgery. Preoperative assessment for both groups included a focused clinical exam with or without functional testing and questionnaires including urogenital distress inventory-6 (UDI-6) and incontinence impact questionnaire-7 (IIQ-7) per the standard clinical practice. All non-exempt women were sent a questionnaire that included UDI-6 and IIQ-7 in addition to standard follow-up questions. Research staff contacted participants via email, mail, and telephone using the same questionnaire template and script. Data was analyzed by using χ2 test for categorical data, and Student’s t test and Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for continuous data. The measure of effect was determined by logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS: A total of 48 women out of 146 selected patients were successfully recruited with n = 22 in the Burch cohort and n = 26 in the control cohort. The mean age was 54.7 ± 7.8 years and mean body mass index was 22.0 ± 13.9 kg/m2. The majority of patients were Caucasian (73.3%), postmenopausal (91.1%), nonsmokers (57.9%), with a history of hysterectomy (81.4%). Six nineteen point six percent of women presented after at least 2 years from placement, which was significantly more common in the Burch cohort. Pain was the most common chief complaint (64.4%) in both groups at the time of initial presentation, and 78.9% of women reported concomitant urinary incontinence. There was no significant difference in pre-operative UDI-6 and IIQ-7 scores between the two cohorts. However, the change in UDI-6 score postoperatively was significantly improved in the Burch cohort with an average drop in score of 28.41 points compared to a decrease of 4.01 points in the control group (P = 0.02, 95%CI: 3.84 to 44.97). Although not statistically significant, the Burch cohort was 58% more likely to show an overall improvement in their score after surgery and 40% more likely to meet the minimal important difference of 11 points (RR = 1.58, 95%CI: 0.97 to 2.57; RR 1.40, 95%CI: 0.79 to 2.46). The difference in IIQ scores was nonsignificant. There was no significant difference in blood loss, complications, or postoperative pain or dyspareunia.

CONCLUSION: Performing a Burch urethropexy during sling removal does not increase complication rates and results in a significant change in validated symptom-related quality of life scores.

Core tip: Performing a concomitant Burch urethropexy at the time of anti-incontinence mesh sling removal is safe and effective.

- Citation: Huber SA, Chinthakanan O, Hawkins S, Miklos JR, Moore RD. Laparoscopic Burch urethropexy at time of mesh sling removal: A cohort study evaluating functional outcomes and quality of life. World J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 5(3): 210-217

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v5/i3/210.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v5.i3.210

Female stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a pervasive condition that affects over 50% women at some point in their lives. Prior to the introduction of synthetic mesh for artificial urethral support, surgical options for management were limited and typically had high failure rates, long operative times, and posed more risk for adverse outcomes. Of these non-synthetic modalities, the Burch urethropexy, or Burch colposuspension, is one of the safest options with proven efficacy[1]. However, the advent of the mesh mid-urethral sling (MUS), including the tension-free vaginal tape, and transobturator tape, single-incision mini-sling, has transformed the management of SUI. This is due in large part to their ease of application, minimally invasive approach, and comparable outcomes to other more involved procedures such as Burch urethropexy[2]. However, the immediate popularity of the synthetic mesh for both anti-incontinence and prolapse led to rapid implementation shortly after arrival to the market without the availability of adequate long-term studies at the time, and eventually mesh-related complications began to acquire widespread media and public attention[3]. In 2008 and 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued warnings regarding the safety of vaginal mesh, indicated either for prolapse or to a lesser extent SUI, based on identifiable risks for mesh erosion, pain, infection and failure[4,5]. Per their independent literature review and investigation of reported incidents, they identified the main adverse outcomes with SUI slings to be pain followed by erosion through the vaginal wall at around 2% prevalence[4,6]. They also cited other deleterious complications such as dyspareunia, bladder injury, nerve injury, urethral or bladder erosions, de novo urgency, urethral obstruction with voiding dysfunction and unresolved SUI[6,7].

Due to the increasing numbers of mesh tape slings placed through the years and possibly the public awareness brought on by the FDA notifications, the true prevalence of symptoms consistent with mesh-tape sling complications is now being appreciated[8]. Given the inherent failure rate of MUS is approximately 10%, specifically recurrence or worsening of SUI, many of these patients also have complaints of SUI in addition to their pain, dyspareunia, or erosion[6]. Furthermore, the presence of these complaints can also suggest misplacement or displacement of the slings which can impact their efficacy.

While conservative measures can be offered to alleviate the patient’s symptoms, approximately 50% of women who present with symptomatic sling complaints will eventually require surgical management after failure of less invasive methods[6,9,10]. However, in most cases removing the sling leaves the patient with recurrent or worsening SUI[6,10]. Historically, treatment for SUI has not been addressed by most during the initial surgery for sling removal and has been delayed until after complete healing from the revision[11]. Although not specifically studied, this is based on the theory that inflammation, blood loss, or an anticipated delay in anatomical restitution following sling removal would either negatively affect the success of a concomitant anti-incontinence surgery or would cause urinary retention from over-correction. However, a delayed secondary surgery for anti-incontinence is not without its own risks, particularly complications surrounding adhesions and scarring from the prior surgeries that can obscure the retropubic space and distort the anatomy. This seems particularly relevant in cases when a retropubic sling is removed, either open or laparoscopically, and the space is entered for removal of the sling[12,13]. To re-enter this space 6 mo later can be very difficult and carries high risks of complications.

In this study, we aim to assess whether performing a combined midurethral mesh sling revision/removal and laparoscopic Burch urethropexy improves postoperative urinary complaints and quality of life without impacting blood loss or complication risk. We theorize that a combined laparoscopic Burch urethropexy will show a significant positive difference in pre- and post-operative validated quality of life and symptomatology questionnaires compared to women who underwent a mesh revision/removal alone.

An internal surgical database review was performed within our two-provider practice isolating patients who underwent a sling removal or revision between 2009 and 2014. Within this group, patients who had a laparoscopic Burch urethropexy at the time of sling removal were placed within a cohort. They were age-matched in a 1:2 ratio to women within the control cohort who underwent a sling removal or revision only. Demographics as well as other relevant medical history were obtained. Preoperative UDI-6 and IIQ-7 scores were calculated when available. The urogenital distress inventory-6 (UDI-6) quantifies the type and severity of urinary incontinence symptoms while the incontinence impact questionnaire-7 (IIQ-7) focuses on the quality of life impact of incontinence. The operative and postoperative notes were reviewed to assess estimated blood loss or complications such as organ injury, hemorrhage, infection, erosion, or urinary retention. Signed informed consent was waived per institutional review board.

Women were excluded if their surgery had been within 6 mo of the study contact period or if they had a multiple stage surgery or repeat surgery. Postoperatively, they were seen in the office for post-operative visits and then contacted by office staff for routine follow-up in four stages via email, mail and telephone to complete repeat UDI-6 and IIQ-7 questionnaires as well as standard follow-up questions regarding specific symptoms, satisfaction, and subsequent treatments. For the phone interviews, the office staff followed a standardized script for routine follow-up if the patient could not come to the office for their follow-up appointments. Data was compiled using Excel 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States) and analysis was performed using SPSS v.22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical data was analyzed using χ2 analysis, and continuous data was analyzed with the Student’s t test and Wilcoxian rank sum test. Relative risks were calculated for outcome comparison, and the measure of effect was calculated with logistic regression analysis. All statistical methodology and data analysis was reviewed by an internal biostatistician.

Differences in pre- and post-operative questionnaire scores were calculated as well as an assessment of likelihood of meeting the minimal clinically important difference (MCID/MID) in scores. Minimal differences in scores must be utilized in analyzing scores to identify any clinically appreciable change in symptoms and validate our findings. According to Barber et al[14,15], the minimal important difference (MID) for the UDI-6 is 11 points and 16 points for the IIQ-7. The percentage of participants in each group with differences greater than the MCID cutoffs have been calculated with relative risks assessed.

At the time of preoperative counseling for sling removal, patients were presented with the following three options: Removal of the sling only without any anti-incontinence surgery, removal of sling with a delayed second stage anti-incontinence surgery at a later date, combined sling removal and Burch urethropexy. Ultimately, the patients selected their preferred option, and this was honored if deemed safe and feasible.

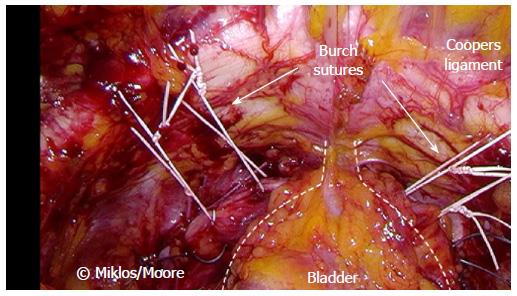

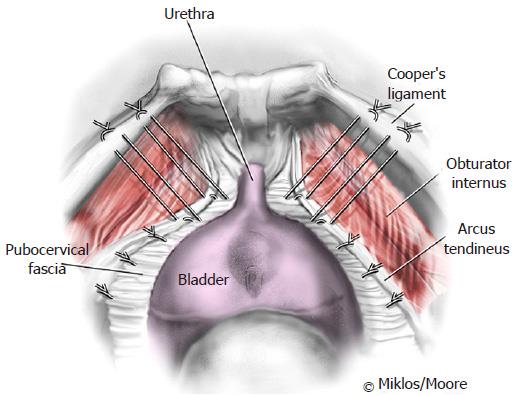

All women underwent sling removal via vaginal approach with additional laparoscopic removal as indicated. Following removal of the sling remnants, a laparoscopic Burch urethropexy and paravaginal repair was performed in the already dissected space of Retzius in selected patients. Two sutures of Ethibond were placed on each side of the bladder neck attaching to Cooper’s ligament (Figures 1 and 2). Cystoscopy was performed at the end of each procedure to ensure correct placement and absence of bladder injury.

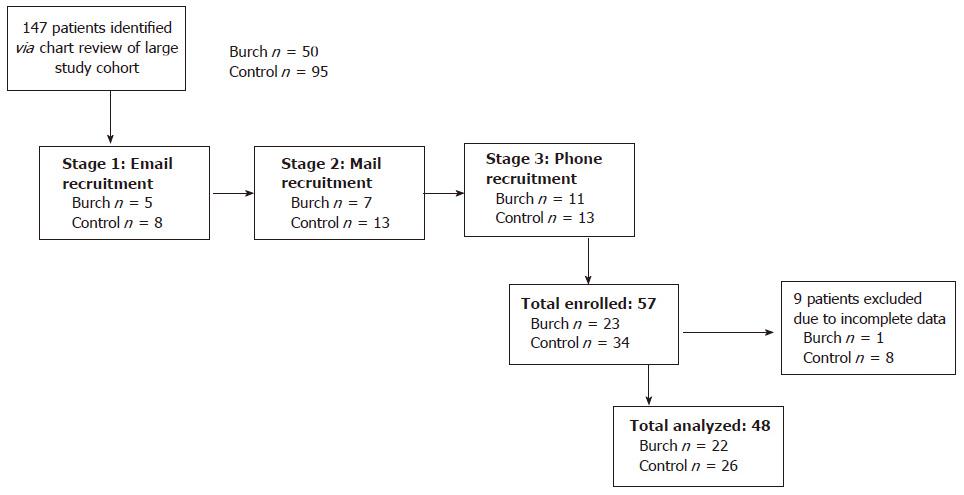

A total of 146 patients met the inclusion criteria of the study, and of those, 48 patients were recruited as postoperative questionnaire respondents with completed prior preoperative questionnaires. Twenty-two women underwent a combined mesh removal and Burch urethropexy, while 26 women were in the matched control cohort (Figure 3). One participant in the control group only completed a UDI-6 questionnaire preoperatively.

The mean age of participants was 54.7 years with no significant difference between the two groups. There was also no difference in BMI, number of vaginal deliveries, race, menopausal status, sexual activity, or smoking history. Ninety-four point seven percent of participants in the Burch group had a prior hysterectomy compared to control group prevalence of 70.8% (P = 0.045). The other significant difference lies in the length of time since placement of sling until surgery. Eighty-five percent of women in the Burch group were at least 2 years out from sling placement which was significantly more compared to the control group at 57.7% (P = 0.046). The average amount of time between surgery and postoperative questionnaire follow-up was significantly longer in the control group, with an average follow-up time of 37.8 mo compared to only 16.7 mo in the Burch group (95%CI: -27.4 to -14.7 mo with P-value < 0.000001) (Table 1).

| Total (n = 48) | Burch (n = 22) | Control (n = 26) | P value (t test, χ2) | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 54.7 ± 7.8 | 55.5 ± 7.8 | 54.0 ± 7.8 | 0.534 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 22.0 ± 13.9 | 24.9 ± 7.2 | 20.3 ± 16.6 | 0.372 |

| Vaginal deliveries (% one or more) | 89.60% | 90.90% | 87.00% | 0.629 |

| Postmenopausal (%) | 91.10% | 95.00% | 88.00% | 0.412 |

| Race | 73.3% Caucasian | 78.6% Caucasian | 68.8% Caucasian | 0.366 |

| Smoking status (%) | 57.90% | 53.30% | 60.90% | 0.898 |

| Hysterectomy (%) | 81.40% | 94.70% | 70.80% | 0.045 |

| Years since insertion (% greater than 2 yr) | 69.90% | 85.00% | 57.70% | 0.046 |

| Urinary incontinence (%) | 78.90% | 90.00% | 66.70% | 0.078 |

| Sexually active (%) | 45.80% | 47.60% | 50.00% | 0.873 |

| Dyspareunia (%) | 93.20% | 88.90% | 96.20% | 0.347 |

The most common complaint in the two groups was pain with the majority of sexually active women reporting dyspareunia (93.2%, P = 0.884). The majority of both women reported subjective urinary incontinence independent of questionnaire scores, comprising 90.0% in Burch group and 66.7% in control group (P = 0.078).

Regarding the surgical outcomes of the two procedures, although length of surgery was not recorded, estimated blood loss and complications rates were not significantly different (Table 2). There were two complications in the Burch urethropexy group, one urethrovaginal fistula and one cystotomy. The only complication in the control group was one retropubic hematoma.

| Burch (n = 22) | Control (n = 26) | P value (t test, χ2) | ||

| EBL (mean mL ± SD ) | 69.29 ± 49.28 | 83.91 ± 165.38 | 0.699 | |

| EBL < 50 mL (%) | 23.80% | 47.8% | 0.222 | |

| EBL 50-100 mL (%) | 47.60% | 34.8% | ||

| EBL 100-300 mL (%) | 28.60% | 13.0% | ||

| EBL > 300 mL (%) | 0.00% | 4.3% | ||

| Complications | Urethrovaginal fistula × 1, cystotomy × 1 | Retropubic hematoma × 1 |

Women were recruited for the study regardless of type of sling, including tension-free vaginal tape, transobturator tape, mini-sling, and women who have multiple slings. Although 50% of women in the Burch group had a transvaginal tape (TVT) sling and 50% of women in the control group had a TOT sling, there was no significant difference in distribution of sling type in each group (Table 3). Forty-three point eight percent of participants had a symptomatic TOT that was removed with a combined laparoscopic Burch urethropexy.

| Overall (n = 48) | Burch (n = 22) | Control (n = 26) | χ2 (P value) | |

| TVT | 37.50% | 50.00% | 26.90% | |

| TOT | 43.80% | 36.40% | 50.00% | |

| Mini-sling | 10.40% | 9.10% | 11.50% | |

| Multiple | 8.30% | 4.50% | 11.50% | 2.97 (0.40) |

Table 4 illustrates the pre and postoperative questionnaire results. In summary, there was no significant difference in the scores between the two groups for either questionnaire both pre and postoperatively. However, the change in UDI-6 score postoperatively was significantly better in the Burch cohort with an average drop in score of 28.41 points compared to a decrease of 4.01 points in the control group (Table 4, P = 0.02, 95%CI: 3.84 to 44.97). When analyzing the percentage of participants who met the MID, or minimally important difference of 11 points, 59% in the Burch group and 42% in the control group met the cutoff. Although not statistically significant, the Burch cohort was 58% more likely to show improvement in their score after surgery (Table 5, RR = 1.58, P = 0.07, 95%CI: 0.97 to 2.57) and 40% more likely to meet the MID (RR = 1.40, P = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.79 to 2.46).

| UDI-6 preop | UDI-6 postop | IIQ-7 preop | IIQ-7 postop | |

| Burch (n = 22) | 78.22 ± 20.45 | 49.81 ± 33.71 | 64.87 ± 31.68 | 48.92 ± 36.33 |

| Control (n = 26 UDI-6 n = 25 IIQ-7)1 | 67.95 ± 27.91 | 63.94 ± 28.67 | 64.11 ± 26.95 | 55.79 ± 34.68 |

| UDI-6 change (mean points ± SD) | 2-sample t test, P value (95%CI) | Relative risk for reduction in score, P value (95%CI) | Relative risk to meet MID, P value (95%CI) | |

| Burch (n = 22) | 28.41 ± 39.29 | 2.39 P value 0.02 | 1.58 P value 0.07 | 1.4 P value 0.25 |

| Control (n = 26) | 4.01 ± 31.50 | (3.84 to 44.97) | (0.97 to 2.57) | (0.79 to 2.46) |

With regards to the IIQ-7 scores, there was no significant difference in temporal change in score. The average change in score was 15.9 points in the Burch cohort and 6.5 in the control cohort (P = 0.440) and a relative risk of overall score reduction of 1.14 (P = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.65 to 1.99). The relative risk for significant score improvement meeting the MID of 16 points is 1.14 (P = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.51 to 2.52).

Although proven effective, and still considered a gold-standard for management of SUI, mesh-based anti-incontinence procedures are not without risks. For many women, the most worrisome of these risks are pain and erosion associated with the synthetic mesh. Oftentimes, this is a protracted process that will only manifest itself years later, leading to the notable increase in complaints years after having the procedure completed. Despite these concerns, mesh tape slings are still considered the standard of care, due to their seven to ten year cure rate of 80%-95%, ease of placement, and relatively low complication profile[2,16]. A patient who suffered from a failed mesh sling or one complicated by pain or erosion, however, may be much more hesitant to have more mesh placed to treat recurrent incontinence, and in the case of mesh-related pain, we would not recommend a second mesh sling[17]. To date, there has been little investigation into the other options available to women requesting mesh removal with persistent or recurrent SUI at the time of removal.

We surmise that for women who refuse additional synthetic mesh, the first-line option should be Burch urethropexy. Due to its long history in practice, the efficacy and risks of the Burch urethropexy have been well established. Additionally, the minimally invasive laparoscopic approach to urethropexy has only enhanced the outcomes and minimized the initial concerns of blood loss and surgical complications[18,19]. Overall, it has been found to have comparable efficacy to mesh tape slings and was the primary anti-incontinence procedure prior to the advent of mesh slings[2]. Ultimately, the numbers of Burch procedures completed in the United States was drastically reduced following the popularization of MUS secondary to the less invasive nature, the simplicity of the procedure and the equivalent cure rates shown for the mesh tape slings. Currently, given the public awareness of mesh complications, the Burch procedure is having a resurgence of popularity as women are seeking alternatives to mesh-tape slings.

To date, no investigation has been performed to determine the best treatment of stress incontinence for women undergoing mesh tape sling removal for complications secondary to the mesh. This sub-type of incontinence patients creates a complicated clinical picture that will require a different approach compared to women without a sling or a sling that does not require removal. Traditionally, women undergo a two-stage surgery with sling removal followed by an anti-incontinence surgery typically 3 to 6 mo later under the assumption that the tissue needs to heal and the anatomy will restitute[11]. However, no clear data has dictated this practice, rather it is mainly based on theory and anecdote[6]. Ideally, these patients would rather be treated at the time of their removal of the bothersome sling without any delay in treated their incontinence and with only one operation, for example via combined mesh tape sling removal and Burch urethropexy.

In assessing the feasibility of performing a combined procedure, we failed to identify any significant difference blood loss or complications when performing a urethropexy immediately following sling removal. From a risk perspective, our data suggests urethropexy at the time of sling revision is of low additional surgical risk, irrespective of the type of sling removed. This is unlike our previous published experience with repeat laparoscopic Burch procedures following previous Burch or marshall-Marchetti-Krantz procedure (MMK). Although successful, we found those procedures to be extremely difficult, increasing risks of complication and blood loss secondary to the increased scar tissue found in the space[10,12,13]. Previous RP sling placement, does not seem to cause as much scar tissue in the space as we have found the dissection and removal relatively straightforward compared to having to enter the space following previous MMK or Burch.

The strengths of our study include the use of validated questionnaires in an attempt to quantify a subjective complaint of urinary incontinence. These were implemented as a standard in our practice in order to provide measurable outcomes to aid in surgical decision-making and for improved patient counseling. As has been proven in the past, the implementation of these questionnaires facilitates improved patient assessment and treatment choices[15]. Another strength lies in the multi-stage approach we standardly use to follow-up with our patients.

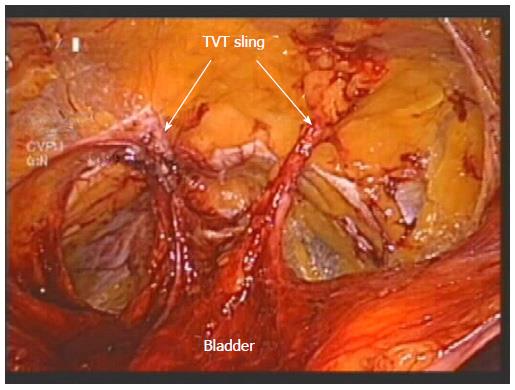

The limitations of this study lie in the small sample size, mainly due to exclusions based on incomplete preoperative data, as well as limited perioperative data and non-randomization of patient treatment. Although there was no significant difference in preoperative urinary incontinence complaints, a Burch urethropexy tended to be performed more frequently in women with this complaint in addition to mesh complication symptoms such as pain and erosion. Furthermore, although non-significant, more Burch urethropexies were performed on women who were undergoing removal or revision of a TVT sling. Due to the location of the TVT sling, a portion of the sling must be removed laparoscopically from the space of Retzius, the same area that requires dissection for a Burch urethropexy, unlike a TOT or mini-sling which does not require intra-abdominal resection (Figure 4).

It is also important to mention the significant differences in prior hysterectomy rates and time between sling insertion and removal. Patients who underwent the Burch procedure were significantly more likely to have a history of hysterectomy (94.7% vs 70.8%, P = 0.045). More patients who had a Burch were greater than 2 years out from sling placement which be associated with higher rates of sling failure, resulting in more pressure to perform anti-incontinence surgery (85.0% vs 57.7%, P = 0.046). Unfortunately, the difference in operative times, surgical cost, and postoperative recovery information such as analgesic usage is not included in this study, but would be of interest in further investigation.

In conclusion, a laparoscopic Burch urethropexy appears to be a safe option for immediate treatment of SUI in women who require sling removal. Further investigation via a larger scale randomized trial with additional focus on perioperative information should be considered to better evaluate outcomes. Our findings should encourage physicians to view treatment of stress incontinence in the setting of a mesh tape sling complication as a symptom that can be managed immediately and effectively. Eliminating the assumed practice of delayed treatment can only bolster patient satisfaction and quality of life.

Suburethral mesh sling complications such as pain or extrusion/erosion are not uncommon and often require revision or removal of the sling. Unfortunately, following removal, patients will typically have persistent or worsening stress incontinence (SUI). There is no clear, concise protocol for optimizing timing and method of treatment for SUI following mesh sling removal.

To date, no study has evaluated the outcome of performing a concomitant procedure at the time of removal to reduce urinary symptomatology. Future research should be undertaken to better assess the options for women with stress urinary incontinence and symptomatic mesh slings. Specifically, comparative evaluations of outcomes following delayed anti-incontinence surgery vs concomitant surgery could provide insight into surgical decision-making.

The authors’ work is the first designed study assessing the feasibility and comparative outcomes of a combined mesh sling removal and laparoscopic Burch urethropexy. Previously, medical knowledge of options for patients with SUI and a symptomatic mesh sling were based solely on theory and isolated case reports without any focused research.

The authors’ goal with the research is to start a dialogue regarding optimizing patient care following symptomatic sling removal. The findings of this study encourage the application of a concomitant surgical approach, showing that it does not increase surgical risk and has a proven effect on postoperative incontinence-related quality of life.

The manuscript conducted a retrospect cohort study to evaluate an immediate laparoscopic Burch urethropexy at the time of mesh sling removal.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Tsikouras PPT, Zhang XQ S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Colombo M, Scalambrino S, Maggioni A, Milani R. Burch colposuspension versus modified Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz urethropexy for primary genuine stress urinary incontinence: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1573-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ogah J, Cody JD, Rogerson L. Minimally invasive synthetic suburethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD006375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anger JT, Weinberg AE, Albo ME, Smith AL, Kim JH, Rodríguez LV, Saigal CS. Trends in surgical management of stress urinary incontinence among female Medicare beneficiaries. Urology. 2009;74:283-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | United States Food and Drug Administration. Considerations about surgical mesh for SUI (2013 [accessed 2016 Feb 26]). Available from: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/UroGynSurgicalMesh/ucm345219.htm. |

| 5. | United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Public Health Notification: Serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence (2008 [accessed 2015 Apr 15]). Available from: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. |

| 6. | Abbott S, Unger CA, Evans JM, Jallad K, Mishra K, Karram MM, Iglesia CB, Rardin CR, Barber MD. Evaluation and management of complications from synthetic mesh after pelvic reconstructive surgery: a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:163.e1-163.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Costantini E, Lazzeri M, Porena M. Managing complications after mid urethral sling for stress urinary incontinence. EAU-EBU Update Series. 2007;5:232-240. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brubaker L, Norton PA, Albo ME, Chai TC, Dandreo KJ, Lloyd KL, Lowder JL, Sirls LT, Lemack GE, Arisco AM. Adverse events over two years after retropubic or transobturator midurethral sling surgery: findings from the Trial of Midurethral Slings (TOMUS) study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:498.e1-498.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Welk B, Al-Hothi H, Winick-Ng J. Removal or Revision of Vaginal Mesh Used for the Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:1167-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Comiter CV. Surgery insight: management of failed sling surgery for female stress urinary incontinence. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2006;3:666-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gebhart JB, Tabuco EC. Management of transvaginal mesh exposure and pain following pelvic surgery (UpToDate, 2015). Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-transvaginal-mesh-exposure-and-pain-following-pelvic-surgery. |

| 12. | Sinha S, Miklos JR, Moore RD. Laparoscopic TVT sling removal following prior transvaginal sling excision. CRSLS. 2014;0095. |

| 13. | Pikaart DP, Miklos JR, Moore RD. Laparoscopic removal of pubovaginal polypropylene tension-free tape slings. JSLS. 2006;10:220-225. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Barber MD, Spino C, Janz NK, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Nager CW, Wheeler TL. The minimum important differences for the urinary scales of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:580.e1-580.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barber MD, Chen Z, Lukacz E, Markland A, Wai C, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Weidner A, Janz NK, Spino C. Further validation of the short form versions of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ). Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:541-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Reich A, Kohorst F, Kreienberg R, Flock F. Long-term results of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure in an unselected group: a 7-year follow-up study. Urology. 2011;78:774-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee D, Zimmern PE. Management of complications of mesh surgery. Curr Opin Urol. 2015;25:284-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moore RD, Speights SE, Miklos JR. Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension for recurrent stress urinary incontinence. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8:389-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Moore RD, Serels SR, Davila GW, Settle P. Minimally invasive treatment for female stress urinary incontinence (SUI): a review including TVT, TOT, and mini-sling. Surg Technol Int. 2009;18:157-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |