Published online Aug 10, 2015. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v4.i3.58

Peer-review started: March 16, 2015

First decision: April 10, 2015

Revised: May 16, 2015

Accepted: July 16, 2015

Article in press: July 18, 2015

Published online: August 10, 2015

Processing time: 159 Days and 10.6 Hours

In women at risk for an ectopic pregnancy, every effort should be made to exclude the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy before embarking on an irreversible treatment for ectopic pregnancy. The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, unless directly visualized with transvaginal ultrasound, is made with the exclusion of an intrauterine pregnancy. Measurement of human chorionic gonadotrophin and progesterone levels, and transvaginal ultrasound are the tools used to evaluate early pregnancy. In women at risk for an ectopic pregnancy, every effort should be made to exclude the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy before embarking on an irreversible treatment course. Methotrexate is an antimetabolite that inhibits DNA synthesis and repair and cell replication. It is administered to ostensible destroy a pregnancy, especially ectopic pregnancies. When administered to an intrauterine pregnancy, embryonic death and missed abortion is the most common result, but early embryos that survive this exposure are likely to have multiple anomalies. The mistaken administration of methotrexate to an intrauterine pregnancy is made because of misinterpretation of the discriminatory zone of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), misinterpretation of early hCG serum levels, misinterpretation of early transvaginal ultrasound images, and failure to clinically correlate hCG levels and ultrasound findings.

Core tip: In women at risk for an ectopic pregnancy, every effort should be made to exclude the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy before embarking on an irreversible treatment course. Methotrexate is an antimetabolite that inhibits DNA synthesis and repair and cell replication. It is administered to ostensible destroy a pregnancy, especially ectopic pregnancies. When administered to an intrauterine pregnancy, embryonic death and missed abortion is the most common result, but early embryos that survive this exposure are likely to have multiple anomalies.

- Citation: Fylstra DL. Avoiding misdiagnosing an early intrauterine pregnancy as an ectopic pregnancy. World J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 4(3): 58-63

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v4/i3/58.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v4.i3.58

In women at risk for an ectopic pregnancy, every effort should be made to exclude the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy before embarking on an irreversible treatment for ectopic pregnancy, such as the administration of methotrexate. When methotrexate is administered to an intrauterine pregnancy, embryonic death with missed abortion is the most common result, but case reports of methotrexate embryopathy have described embryos that have survived early methotrexate exposure.

This is a clinical perspective from experience with cases when methotrexate has been mistakenly administered to an undiagnosed intrauterine pregnancy. Included is a review of serum hCG and progesterone levels and ultrasound interpretation.

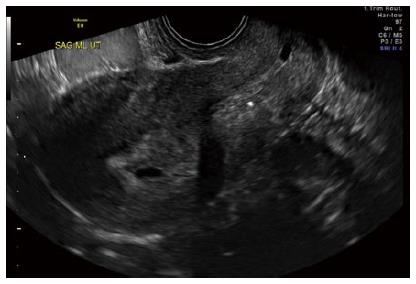

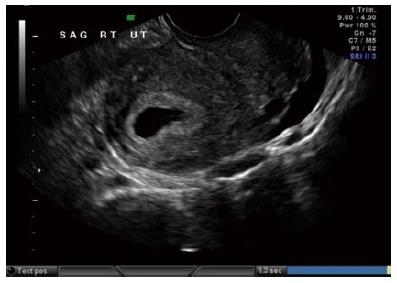

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, unless directly visualized with transvaginal ultrasound, is made with the exclusion of an intrauterine pregnancy. The confirmation of an intrauterine pregnancy with transvaginal ultrasound relies upon recognition, initially of a true gestational sac, followed soon thereafter, by recognition of structures within the sac consistent with a developing embryo. The term “gestational sac” is a sonographic term and not an anatomical structure. A true gestational sac has a thick echogenic rim, a trophoblastic decidual reaction, surrounding a sonolucent center, the chorionic sac[1]. The intradecidual sign is the presence of such a sac buried beneath the surface of the endometrium, appearing eccentrically positioned within the endometrium (Figure 1). A “pseudosac” is a collection of fluid within the endometrial cavity itself, created by bleeding from the decidualized endometrium associated with an extrauterine pregnancy implantation (Figure 2). The precise location of such an early sonolucent uterine fluid collection should distinguish between a true gestational sac and a pseudosac.

Prior to the recognition on a definite intrauterine pregnancy, transvaginal ultrasound measurement of the endometrial echo thickness in early gestation can be helpful in predicting pregnancy location. Spandorfer et al[2] reporting on 117 pregnancies with a gestational age between 5.3 and 6.3 wk found statistically different endometrial echo thicknesses between patients who eventually had normal intrauterine, failed intrauterine, and ectopic gestations. Patients with normal pregnancies had endometrial echo thicknesses of 13.42 ± 0.68 mm. In contrast, those with failed intrauterine and ectopic gestations measured 9.28 ± 0.88 mm and 5.95 ± 0.35 mm, respectively (P < 0.01). In this report, 97% of patients with an echo no greater than 8 mm had abnormal pregnancies, and 71% of these abnormal pregnancies were ectopic in location. Only 41% of those patients with an echo thickness greater than 8 mm were abnormal, and only 14.7% were ectopic in location. No patient with an endometrial echo thickness greater than 13 mm had an ectopic pregnancy, and no patients with an echo thickness less than 6 mm had a normal pregnancy. Other authors have not been able to duplicate these discrete, well-stratified echo thickness separations[3-5]. Therefore, such absolute endometrial thickness numbers cannot be absolutely relied upon, but attention to endometrial thickness can be helpful in predicting pregnancy location, especially when the endometrial thickness is very thin or very thick.

The “discriminatory zone” of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) is that level of serum hCG at which a normal and singleton gestation can be visualized within the endometrial cavity with transvaginal ultrasound. Depending upon the lab and the reference standard used, that hCG level is 1500 to 2000 mIU/mL. A failing pregnancy, including an ectopic implantation, should be considered, but is not confirmed, when this hCG threshold is reached and an intrauterine gestational sac is not seen with transvaginal ultrasound[6].

The possibility of ectopic pregnancy is frequently considered before hCG has reached the discriminatory zone and before ultrasound recognition[7]. Human chorionic gonadotropin rises exponentially in early normal pregnancy and should rise at least by 53% in 48 h[8]. This exponential rise is less reliable after 10000 mIU/mL, and at this level pregnancy is better evaluated with ultrasound. Fifteen percent of normal intrauterine pregnancies can demonstrate an abnormal early rise of hCG, but for the majority of gestations, when the hCG rise is abnormal, at a plateau, or falling, an abnormal pregnancy is confirmed, but not its location[9].

When exact pregnancy dating is available, an intrauterine pregnancy, regardless of embryonic number, should be identified within the endometrial cavity with transvaginal ultrasonography by 24 embryonic days, or 38 menstrual days (exact 28 d menstrual cycle)[10]. This exact pregnancy dating does not rely on human chorionic gonadotropin levels. Therefore, failure to identify an intrauterine pregnancy with such exact dating is presumptive evidence of a failing pregnancy, which could be ectopic in location. Without such exact pregnancy dating, and with no intrauterine pregnancy identified with transvaginal sonography: the “non-diagnostic ultrasound”, a serum level of hCG is needed for ultrasound interpretation[10].

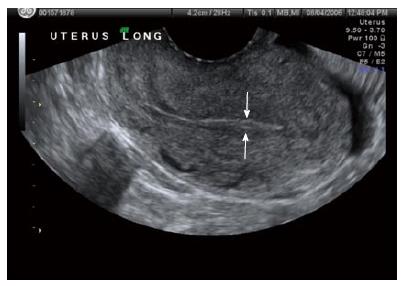

Usually, the transvaginal ultrasound identification of an intrauterine pregnancy reliably excludes an extrauterine implantation. A yolk sac is the first visible structure within the gestational sac, and is a distinct circular structure with a bright echogenic rim and sonolucent center (Figure 3), and is recognized 3 wk post-conception (5 wk after the last menstrual period). The embryo is first recognized as a thickening along an edge of the yolk sac, and embryonic cardiac motion can be first observed 31/2 to 4 wk post-conception (51/2-6 wk after last menstrual period).

An exception to the above is the presence of a heterotopic pregnancy: the co-existence of an extrauterine implantation with an intrauterine pregnancy. Traditionally, the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy in spontaneous cycles has been reported to be 1 in 30000 pregnancies[11]. However, its incidence is actually 1 in 3889 pregnancies[12]. The incidence is even higher (1 in 100 pregnancies) in women conceiving with in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer[13]. Should a clinical presentation or abnormal pelvic ultrasound appearance suggest an ectopic pregnancy, despite visualization of an intrauterine gestation, the diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy should be considered, with the probable need for diagnostic laparoscopy confirmation and treatment.

A serum progesterone level can be helpful when the hCG is elevated, the endometrial echo is thickened and no gestational sac is seen. In a study spanning several years and yielding 3674 consecutive emergency room pregnant women visits, a serum progesterone level less than 5 ng/mL had a specificity of nearly 100% in detecting a failing pregnancy[14,15]. Therefore, with this low progesterone level, uterine curettage can be used to differentiate between a failing intrauterine pregnancy and an ectopic without the fear of interrupting a normal intrauterine pregnancy. When chorionic villi are seen on pathology, the diagnosis is a failed intrauterine pregnancy. If no chronic villi are retrieved from the uterus, the pregnancy is somewhere else. An exception to this would be with a history of heavy vaginal bleeding consistent with a completed spontaneous pregnancy loss. Therefore, after uterine evacuation and absent chorionic villi, hCG should be re-measured. A falling hCG level would support the diagnosis of a spontaneous loss, and continued observation is recommended. With a post uterine evacuation persistently elevated hCG, ectopic pregnancy is confirmed.

Methotrexate is an antimetabolite that binds to the catalytic site of dihydrofolate reductase, interrupting the synthesis of purine nucleotides and the amino acids serine and methionine, thus inhibiting DNA synthesis and repair and cell replication. It affects actively proliferating tissues such as bone marrow, buccal and intestinal mucosa, respiratory epithelium, malignant cells, and trophoblastic tissue. Systemic methotrexate has been used to treat gestational trophoblastic disease since 1956 and was first used to treat ectopic pregnancy in 1982[16]. It is administered to ostensible destroy a pregnancy, especially ectopic pregnancies. When administered to an intrauterine pregnancy, embryonic death and missed abortion is the most common result, but case reports of methotrexate embryopathy have described embryos that have survived early methotrexate exposure[17-23]. The gestational age at exposure to methotrexate is critical for the type of malformations observed[17-23]. In particular, exposure at 5 to 6 wk gestation, which is often the case in misdiagnoses of ectopic pregnancy, may lead to methotrexate embryopathy, including musculoskeletal, conotruncal, cardiac and central nervous system abnormalities[17-23]. Cardiac defects include Tetralogy of Fallot, perimembranous ventricular septal defect, patent foramen ovale, and increased pulmonary artery pressures. Intrauterine growth restriction occurs, and, after delivery, neurodevelopmental delay is common.

Administration of methotrexate to a woman with a presumptive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, which eventually turns out to have an intrauterine pregnancy, results from the following:

As stated, the discriminatory level of hCG is defined by a “normal and singleton” gestation, i.e., a single embryo pregnancy that is living and intrauterine. If a pregnancy is not seen within the endometrial cavity with transvaginal ultrasound when the hCG level has reached the discriminatory zone, an ectopic pregnancy may be suspected, but is not diagnosed with certainty. A single early hCG level is only a marker for gestational age, and clinical parameters are more important in the decision-making process. An early multiple gestation may not be seen when the singleton hCG discriminatory level has been reached, and this should especially be considered in those women who have conceived with assisted reproduction. Also, because an abnormal pregnancy would be expected to have a lower hCG level at any given gestational age, delaying the performance of a vaginal ultrasound until the hCG level has reached the discriminatory level could miss the early opportunity to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy.

Because of the variation in vaginal ultrasound technical and interpretive abilities and laboratory hCG levels, before embarking on treatment for a presumed ectopic pregnancy, especially with methotrexate, every pregnancy should be given the benefit of the doubt, even if undesired. The diagnosis may require the use of diagnostic laparoscopy for confirmation or, simply, more time and serial measurements of hCG and serial ultrasounds until the diagnosis is certain.

Barnhart, etal, have redefined early hCG curves[8]. They report a cohort of women who presented with abdominal pain and/or vaginal bleeding, symptoms which would place these women at risk for ectopic implantation, but who eventually had normal intrauterine pregnancies. Ninety-nine percent of these early normal intrauterine pregnancies demonstrated an early hCG rise of at least 53% in 48 h. Relying on hCG measurements less than after a true 48 h interval or the use of the old concept of true doubling or a 66% rise in 48 h could misdiagnose an intrauterine pregnancy as an ectopic[10].

In a woman with a positive pregnancy and before the recognition of an intrauterine pregnancy with transvaginal ultrasound, endometrial echo thickness can be evaluated (Figures 4 and 5). As stated before, endometrial echo thickness can be helpful, but not definitive, in diagnosing pregnancy location: the thinner the endometrial echo, especially when less than 8 mm, the more likely the gestation is an ectopic implantation[2]. As stated before, absence of an intrauterine gestational sac on transvaginal ultrasound is not diagnostic of an extrauterine implantation, and clinical parameters must be considered in addition to absolute hCG levels, and because of the variation in the technical quality and interpretive ability of vaginal ultrasound and variation in laboratory hCG levels, the diagnoses of an ectopic pregnancy should not be made based on a single non-diagnostic ultrasound or a single hCG level. Furthermore, the location and appearance of an early intrauterine fluid collection may not always meet the criteria for a true gestational sac: eccentrically located sonolucent area surrounded by an echogenic rim.

Emergency room bedside sonography performed by emergency room personnel may differ significantly in quality and protocol from sonography performed by radiologists or trained gynecologists. A recent emergency room study reported that within a group of 161 women who were eventually proven to have a living intrauterine pregnancy, 47 (29%) were missed with initial emergency room bedside sonography with hCG levels as high as 100000 mIU/mL (mean hCG level of missed intrauterine pregnancies was 6633 mIU/mL)[21]. When the transvaginal ultrasound imaging interpretation is rendered by an emergency room physician or a radiologist, it would be prudent for the treating gynecologist to view the ultrasound images and discuss the findings with the other physician before embarking of treatment of a suspected ectopic pregnancy. Unless absolutely diagnostic, caution is recommended in interpreting a single hCG level and a single ultrasound image.

The true overall incidence of methotrexate exposure to early intrauterine pregnancies is unknown and probably under reported because few cases are found in the medical literature. Every effort should be made to exclude an intrauterine pregnancy before embarking on an irreversible ectopic pregnancy treatment course, i.e., methotrexate. Unless a clinical emergency exists, which would also be a contraindication to medical management, expectant management with follow up hCG levels and follow up ultrasound imaging will eventually lead to the correct diagnosis. Administration of methotrexate is never an emergency. Laparoscopy confirmation should not be disregarded when felt clinically appropriate. A thickened endometrial echo without a gestation sac needs follow up ultrasound imaging. Any intrauterine fluid collection should be considered a probable gestational sac until proven otherwise. A low serum progesterone can justify endometrial curettage to differentiate between a failing intrauterine pregnancy and an ectopic pregnancy. The rise of hCG should be interpreted in view of the new hCG curves.

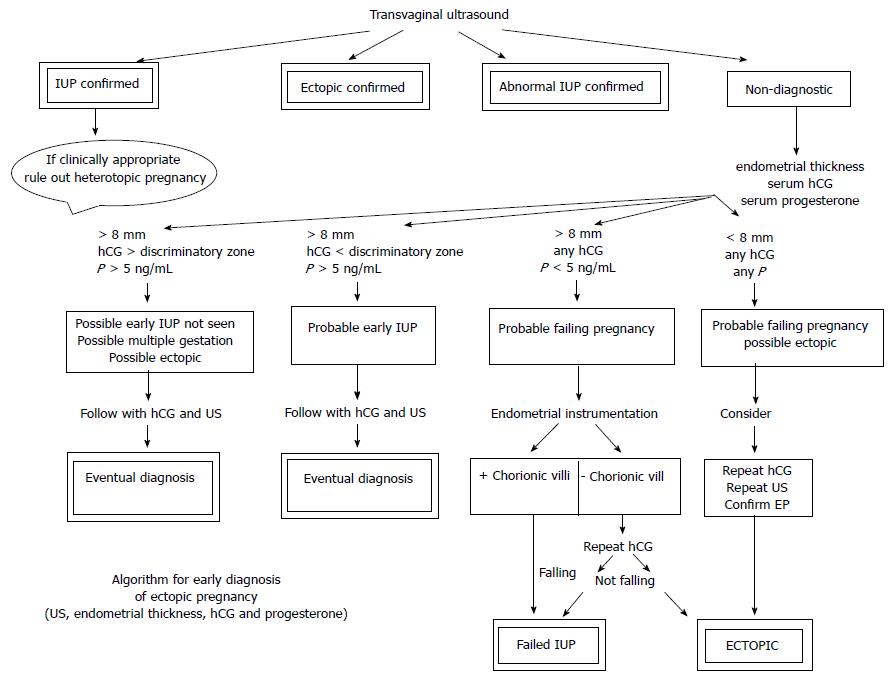

Figure 6 is a suggested non-surgical diagnostic algorithm utilizing these diagnostic principles. The algorithm has not been tested to yield sensitivity, specificity, positive or negative predictive values, but adds the evaluation of endometrial thickness to the criteria of previous non-surgical algorithms. Every woman with the potential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy should be counseled on the need for close follow up while awaiting diagnostic confirmation, rather than proceeding with an irreversible treatment with only a suspicion.

P- Reviewer: Iavazzo C, Ihab MU, Messinis IE, Xiu QZ S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Fylstra DL. Tubal pregnancy: a review of current diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;53:320-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Spandorfer SD, Barnhart KT. Endometrial stripe thickness as a predictor of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:474-477. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Moschos E, Twickler DM. Endometrial thickness predicts intrauterine pregnancy in patients with pregnancy of unknown location. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:929-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Levgur M, Tsai T, Kang K, Feldman J, Kory LA. Endometrial stripe thickness in tubal and intrauterine pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:889-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Hammoud AO, Hammoud I, Bujold E, Gonik B, Diamond MP, Johnson SC. The role of sonographic endometrial patterns and endometrial thickness in the differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1370-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 94: Medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1479-1485. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ankum WM, Van der Veen F, Hamerlynck JV, Lammes FB. Suspected ectopic pregnancy. What to do when human chorionic gonadotropin levels are below the discriminatory zone. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:525-528. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Rinaudo PF, Zhou L, Hummel AC, Guo W. Symptomatic patients with an early viable intrauterine pregnancy: HCG curves redefined. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Kadar N, Caldwell BV, Romero R. A method of screening for ectopic pregnancy and its indications. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:162-166. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kadar N, Bohrer M, Kemmann E, Shelden R. The discriminatory human chorionic gonadotropin zone for endovaginal sonography: a prospective, randomized study. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:1016-1020. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Reece EA, Petrie RH, Sirmans MF, Finster M, Todd WD. Combined intrauterine and extrauterine gestations: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:323-330. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Schroeppel TJ, Kothari SN. Heterotopic pregnancy: a rare cause of hemoperitoneum and the acute abdomen. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006;274:138-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Svare J, Norup P, Grove Thomsen S, Hornnes P, Maigaard S, Helm P, Petersen K, Nyboe Andersen A. Heterotopic pregnancies after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer--a Danish survey. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:116-118. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Stovall TG, Ling FW, Carson SA, Buster JE. Serum progesterone and uterine curettage in differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:456-457. [PubMed] |

| 15. | McCord ML, Muram D, Buster JE, Arheart KL, Stovall TG, Carson SA. Single serum progesterone as a screen for ectopic pregnancy: exchanging specificity and sensitivity to obtain optimal test performance. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:513-516. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Tanaka T, Hayashi H, Kutsuzawa T, Fujimoto S, Ichinoe K. Treatment of interstitial ectopic pregnancy with methotrexate: report of a successful case. Fertil Steril. 1982;37:851-852. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Nguyen C, Duhl AJ, Escallon CS, Blakemore KJ. Multiple anomalies in a fetus exposed to low-dose methotrexate in the first trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:599-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Addar MH. Methotrexate embryopathy in a surviving intrauterine fetus after presumed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy: case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26:1001-1003. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Usta IM, Nassar AH, Yunis KA, Abu-Musa AA. Methotrexate embryopathy after therapy for misdiagnosed ectopic pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:253-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Hyoun SC, Običan SG, Scialli AR. Teratogen update: methotrexate. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:187-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Wang R, Reynolds TA, West HH, Ravikumar D, Martinez C, McAlpine I, Jacoby VL, Stein JC. Use of a β-hCG discriminatory zone with bedside pelvic ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:12-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Poggi SH, Ghidini A. Importance of timing of gestational exposure to methotrexate for its teratogenic effects when used in setting of misdiagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:669-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Nurmohamed L, Moretti ME, Schechter T, Einarson A, Johnson D, Lavigne SV, Erebara A, Koren G, Finkelstein Y. Outcome following high-dose methotrexate in pregnancies misdiagnosed as ectopic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:533.e1-533.e3. [PubMed] |