Published online Feb 10, 2015. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v4.i1.9

Peer-review started: June 20, 2014

First decision: July 21, 2014

Revised: October 14, 2014

Accepted: October 29, 2014

Article in press: October 29, 2014

Published online: February 10, 2015

Processing time: 120 Days and 11 Hours

AIM: To explore the prevalence of post-partum depression (PPD) in coeliac disease (CD).

METHODS: We performed a case-control study evaluating the prevalence of PPD in CD patients on gluten-free diet (GFD) compared to that of healthy subjects experiencing a recent delivery. All participants were interviewed about menstrual features, modality and outcome of delivery and were evaluated for PPD by Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

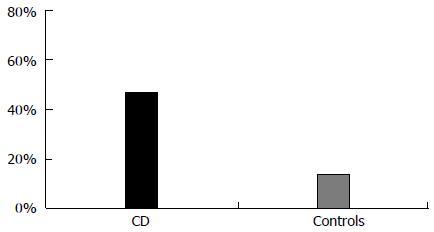

RESULTS: The study included 70 CD patients on GFD (group A) and 70 controls (group B). PPD was present in 47.1% of CD women and in 14.3% of controls (P < 0.01; OR = 3.3). Mean EPDS score was higher in CD compared to the controls (mean score: group A 9.9 ± 5.9; group B 6.7 ± 3.7; P < 0.01). A significant association was observed between PPD and menstrual disorders in CD (69.7% vs 18.9%; P < 0.001; OR = 3.6).

CONCLUSION: PPD is frequent in CD women on GFD, particularly in those with previous menstrual disorders. We suggest screening for PPD in CD for early detection and treatment of this condition.

Core tip: Some studies have shown an increased prevalence of psychological symptoms and mental disorders in patients affected by coeliac disease (CD) and depression appears to be the most important condition in undiagnosed CD. On the other hands, focused data on post-partum depression are still lacking. In our mind, the present work is the first study mainly focused on this interesting and relevant topic.

- Citation: Tortora R, Imperatore N, Ciacci C, Zingone F, Capone P, Siniscalchi M, Pellegrini L, Stefano GD, Caporaso N, Rispo A. High prevalence of post-partum depression in women with coeliac disease. World J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 4(1): 9-15

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v4/i1/9.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v4.i1.9

Coeliac disease (CD) is a chronic small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by the exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals[1,2]. CD is the most common cause of enteropathy in the western world and affecting around 1% of the general population in both children and adults[3].

Gluten consumption in these susceptible individuals leads to small bowel damage and the activation of immune responses which cause both intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations of the disease.

About clinical features, as reported in a recent article by Ludvigsson et al[1], classical CD is characterized by signs and symptoms of malabsorption (diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, weight loss, etc.), while non-classical CD presents with anaemia, osteopenia/osteoporosis, recurrent abortions, hepatic steatosis, dental enamel hypoplasia, hypertransaminasemia, recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

At present, CD diagnosis requires first of all a serological screening of patients with suspected CD using anti-tissue transglutaminase (a-tTG) and anti-endomysial antibodies and then, a duodenal biopsy to assess the intestinal damage in patients with positive serology[1].

Many studies have shown an increased prevalence of psychological symptoms and mental disorders in patients affected by CD and depression appears to be the most important condition in undiagnosed CD[4-7]. In effect, Addolorato et al[8] reported that the prevalence of depression in CD patients was significantly higher than in the control group (57.1% vs 9.6%). In addition, recent reports have revealed a high prevalence of anxiety and sleep disorders in coeliac patients, so confirming the importance of exploring and treating mental aspects in this particular population[8,9].

Post-partum depression (PPD) affects 10%-15% of new mothers being the most common complication of pregnancy in developed countries[10,11]. This condition is often unrecognized and when left untreated can be associated with potentially adverse consequences for the mother, her infant, and her family. In particular, PPD can lead to disruptions in maternal-infant interactions, and lower cognitive functioning and behavioural problems in children[12,13]. Even if PPD is underdiagnosed, a number of important risk factors (past depression, stressful life events, poor marital relationship, and social support) have been described and can be utilised as helpful risk factors for suspecting development of the condition[14-16].

On the basis of these assumptions, consideration should be given to screening for PPD, although evidence in support of universal screening tools is lacking. However, women with known risk factors for PPD may be selected for screening[17,18]. At present the most utilised tool for screening PPD is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) which consists in a 10-item self-rated questionnaire with a diagnostic cut-off of 10 (or greater) for possible PPD[19-22] even though the sensitivity and specificity varies across languages and cultures[23].

Even if many studies have clearly shown the high prevalence of depression and other mental disorders in CD, specific data on PPD in CD women are still lacking.

Aim of this study was to explore the prevalence of PPD in women suffering from CD compared to that recorded in healthy subjects.

We performed a case-control study evaluating the prevalence of PPD in CD patients on gluten-free diet (GFD) in comparison with a control group of healthy subjects.

Between June 2010 and February 2013 we enrolled all coeliac women (Group A) followed-up at our Gastrointestinal Unit (tertiary centre for food intolerance and CD) who had given birth within the 8-wk period preceding their appointment at the Unit and had been on GFD for at least 1 year before pregnancy. CD patients were also classified in accordance with Oslo classification[1]. A group of consecutive healthy women who had given birth in the previous 8 wk were also recruited at two first-line obstetric Clinics as control group (Group B). The clinical interview was conducted postnatally by gastroenterologists not blinded on the clinical/pathological state of the subject. All women (CD patients and controls) with a diagnosis of active depression (based on DSM-IV criteria) formulated at least 3 mo before starting pregnancy and those already on treatment with anti-depressant drugs were excluded from the study.

A gynaecological evaluation explored menstrual cycle features, potential comorbidities, mode and outcome of delivery. Menstrual disorders were defined in presence of amenorrhea, dysmenorrhoea, pre-menstrual syndrome, polymenorrhea and oligo-menorrhea in accordance with the gynaecological literature[24,25]. All women underwent a conventional serological evaluation comprising the detection of tissue anti-transglutaminase antibodies level.

All participants were assessed blinded for PPD through clinical interview using the EPDS[19-22].

Furthermore, quality of life as defined through the SF-36 questionnaire was examined in all patients and controls[26-29].

All patients gave their written consent to participate in the study that was approved by local Ethical Committee.

EPDS is a 10-item (scored on a scale of 0-3) self-reported scale assessing the symptoms of PPD. This questionnaire has been validated also in Italy[30] so that we were able to use it for the population in our study with high values on diagnostic accuracy. EPDS is routinely used in many clinical services to screen for probable distress in women, both antenatally and postnatally, with a diagnostic cut-off ≥ 10 (sensitivity 96%; specificity 92%)[31]. On these grounds, we established a cut-off ≥ 10 as highly indicative of possible PPD. CD patients and controls with a EPDS ≥ 10 were referred for psychiatric assessment. The screening for PPD was performed by an interviewer using the EPDS score with a ≥ 10 cut-off and a clinical interview performed by an expert psychiatrist according to the DSM IV-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision).

The SF-36 survey consists of a 36-item questionnaire that includes eight components: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional and mental health issues. These eight domains form two broader health dimension scales: the physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component scales. The SF-36 subscales and composite scores can be summarised through means ± SD, with higher scores indicating better health and well-being. Low scores on the PCS indicate limitations in physical functions and general health, and/or physical pain, while higher scores suggest no physical limitations, disabilities, or reductions in well-being. Similarly, low scores on the MCS suggest frequent experience of difficulties in psychosocial health, emotional problems and reduced vitality, while high scores indicate frequent positive affect and vitality, the absence of psychological distress and reduced or no limitations in daily social activities[26-29].

We estimated that a sample size of 67 participants would be able to offer a 80% power to detect a 20% difference between the two groups (when assuming a known PPD prevalence of 13% in general population)[10,11].

Statistical analysis was performed by using χ2, Mann Whitney U test and odd ratio (OR) calculation when indicated; differences were considered significant with a P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with software package SPSS for Windows (Rel SPSS 14.0; SPSS Chicago, IL).

The study included 70 CD patients on GFD (group A) and 70 healthy controls (group B). According to the Oslo classification[1], CD patients were classified as classical CD in 31 cases (44%), non-classical CD in 34 subjects (49%), asymptomatic CD in 5 patients (7%). About symptoms of CD patients, 30 subjects (43%) showed anaemia, 31 (44%) had diarrhoea, 33 (47%) presented weight loss, 26 (37%) showed abdominal pain and 28 (40%) asthenia.

Group A and Group B resulted well matched for age (group A: 33.3 ± 2.9 years; group B: 32.3 ± 4.3 years; P = NS) and level of school education (group A: 11.1 ± 3.5; group B: 11.3 ± 3.9; P = NS).

No significant difference was evident between the two groups in terms of laboratory variables: haemoglobin (group A: 11.03 ± 2.46; group B: 11.21 ± 2.54; P = NS); cholesterol (group A: 156.85 ± 35.82; group B: 149.68 ± 37.02; P = NS); glycaemia (group A: 80.6 ± 10.3; group B: 79.81 ± 13.3; P = NS); alanine transaminase (group A: 25.41 ± 12.6; group B: 24.18 ± 11.9; P = NS). Demographic and serological features of patients and controls are reported in Table 1. The level of anti-transglutaminase antibodies was normal for all participants (CD patients on GFD and controls).

| Group ACeliac women(# 70) | Group BHealthy subjects(# 70) | P value | |

| Mean age (yr) | 33.32 ± 2.88 | 32.32 ± 4.32 | 0.7 |

| Level of instruction (yr) | 11.06 ± 3.54 | 11.30 ± 3.58 | 0.9 |

| Hb (gr/dL) | 11.03 ± 2.46 | 11.21 ± 2.54 | 0.7 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 156.85 ± 35.82 | 149.68 ± 37.02 | 0.2 |

| Anti-transglutaminase IgA (U/mL) | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Type of childbirth | |||

| Delivery by caesarean section | 36/70 | 31/70 | 0.7 |

| Vaginal delivery | 34/70 | 39/70 | 0.7 |

| Outcome of birth | |||

| Live birth | 70/70 | 70/70 | 1.0 |

| Congenital malformations | 0/70 | 1/70 | 0.9 |

| Number of pregnancies | |||

| First pregnancy | 34/70 | 37/70 | 0.7 |

| Second pregnancy | 25/70 | 24/70 | 0.9 |

| > 2 pregnancies | 11/70 | 9/70 | 0.8 |

| Weeks of gestation | 37.7 ± 1.78 | 37.95 ± 1.43 | 0.9 |

Thirty-three subjects in Group A and 10 in Group B had EPDS scores higher than the selected cut-off (47.1% of CD patients vs 14.3% of controls; P < 0.01; OR = 3.3). The Figure 1 shows the prevalence (%) of positive EPDS for PPD in CD women and controls. EPDS score was higher in CD women compared to the controls (mean score: group A 9.9 ± 5.9; group B 6.7 ± 3.7; P < 0.01). After psychiatric assessment, 29 out of the 33 patients in Group A (prevalence 41%) and 8 out of the 10 people in the control group (prevalence 11%) with high EPDS scores received a diagnosis of PPD. These results confirmed the high sensitivity of EPDS in our country (sensitivity 86%). The majority of patients suffered from a mild form of PPD received only active psychological support; only 6 patients (16%) needed anti-depressants and long-term psychiatric follow-up. Results are reported in Table 2.

| Group ACeliac womenn = 70 | Group BHealthy subjectsn = 70 | P value | |

| EPDS score (mean ± SD) | 9.94 ± 5.98 | 6.7 ± 3.73 | < 0.01 |

| Patients with EPDS score ≥ 10 (%) | 33/70 (47) | 10/70 (14) | < 0.01 |

| PPD after psychiatric assessment | 29/33 | 8/10 | 0.06 |

| SF-36 | |||

| PCS (mean ± SD) | 55 ± 12 | 66 ± 8 | 0.03 |

| MCS (mean ± SD) | 43 ± 11 | 56 ± 7 | 0.02 |

Regarding the circumstances of delivery, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of type of delivery (group A: caesarean section delivery 51.4%; vaginal delivery 48.6%; group B: caesarean section delivery 44.3%; vaginal delivery 55.7%; P = NS) and birth outcomes (live birth: group A 100%; group B 100%; congenital malformations: group A 0%; group B 1.5%; P = NS). On the contrary, a significant association was observed between the onset of PPD and a previous menstrual disorder in women suffering from CD. Among these, 23 women with and only 7 without previous gynaecological diagnosis of menstrual disorders were positive for PPD at EPDS (69.7% vs 18.9%; P < 0.001; OR = 3.6); this association was not evident in the control group (25% vs 33%; P = 0.4).

With regard to quality of life as measured by the SF-36, outcomes were significantly better in controls than in patients with CD in terms of both PCS (55 ± 12 in Group A vs 66 ± 8 in Group B; P = 0.03) and MCS (43 ± 11 in Group A vs 56 ± 7 in Group B; P = 0.02). These outcomes were significantly and inversely correlated with the presence of PPD (P = 0.02).

The present study, focused on PPD, has shown a higher prevalence of this condition in women affected by CD on GFD when compared to healthy subjects (47% vs 14%); after psychiatric assessment, the prevalence of PPD was 41% in CD patients compared to 11% of control group. To our knowledge, this is the first paper reporting a higher incidence of this kind of psychiatric condition in CD.

Many studies have evaluated the psychiatric/mental aspects of CD[4,6,7]. In particular, a recent meta-analysis has clearly shown that depression is consistently more common and severe in adults with CD than in healthy adults[32]. After the diagnosis of CD, these patients must avoid foods containing grains (wheat, rye, and barley) for the rest of their life. From this point of view, depression in adult CD may represent a non-specific disorder precipitated by adverse physical symptoms along with personal and social limitations imposed by the chronic disease and the related dietary restrictions.

In effect, in terms of clinical depression, adults affected by CD do not differ substantially from those with other types of physical illness. In addition, many reports have underlined the high prevalence in patients with CD compared to healthy control groups of other psycho-pathological conditions, such as anxiety and sleep disorders[5,8,9].

In our study, a probable diagnosis of PPD identified on the basis of EPDS questionnaire scores was subsequently confirmed through psychiatric assessment in a majority of cases (sensitivity: 86%).

Although frequent, PPD was mild in most affected CD patients and was effectively treated by psychological support. This finding is in accordance with previous reports showing a high rate of missed diagnosis of PPD in the general population, especially if PPD presented in a mild form[33]. The screening approach led to early diagnosis and treatment in 43 women (33 CD, 10 controls) affected by PPD, potentially preventing negative consequences for mothers and their newborns.

The high prevalence of PPD in our CD population could be due to several causes. Firstly, PPD could be the expression of an underlying subclinical depression which develops features of PPD and clinical relevance during pregnancy or immediately after childbirth as a result of the heightened anxiety that can be typical of this period. This hypothesis is also in accordance with the low level of quality of life of CD patients compared to the controls[9,34]. On these bases, it is possible that a substantial proportion of the PPD cases were also mildly symptomatic during pregnancy so that the screening for and treating depression in CD patients during pregnancy might be more beneficial than waiting to screen them in the postnatal period. Many studies have highlighted the close relationship between low quality of life, anxiety and depression in patients with CD and, from this point of view, our findings are not surprising[4,9]. In addition, a woman suffering from CD may be concerned about the possible “genetic transmission” of CD to the newborn, thus worsening her anxiety.

Another explanation for our results could be found in inflammatory/autoimmune mechanisms. Many reports have investigated and underlined the possible role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of some variants of depression and of other mental problems such as sleep disorders[35,36]. Significant increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and other inflammation-related proteins in major depression were found in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid. Furthermore, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines persist after clinical symptoms of depression are in remission and can also predict the onset of a depressive episode. Antidepressant treatment can lead to a normalization of elevated cytokine levels in major depression[35]. In effect, a recent meta-analysis has investigated the effect of some anti-depressants on the level of inflammatory cytokines. The results of this study underlined that antidepressant treatment is able to reduce levels of IL-1β and possibly those of IL-6. Stratified subgroup analysis by class of antidepressant indicated that serotonin reuptake inhibitors may reduce levels of IL-6 and TNFα[36]. All these consideration could be considered an indirect demonstration of the pivotal role of inflammation in determining depression (and PPD) symptoms.

In our CD population the occurrence of PPD was significantly correlated with the presence of previous menstrual disorders[37]. This result could be the expression of a pre-existing underlying hormonal alteration which can also affect and/or contribute to the incidence of mental disorders[38,39].

Interestingly, a recent paper by Buttner et al[39] has highlighted the significant association between previous menstrual disorder and depression with a twofold increased risk of PPD in women with menstrual irregularities[40]. In our control population this kind of association was not evident, probably because of the small number of controls with PPD (10 patients). Nevertheless, one could postulate that this association may be related to the range of alterations characterising the spectrum of gynaecological/obstetric manifestations of CD[41,42]. Unfortunately, our work did not include investigations for the measurement of sexual and other hormones and this hypothesis remains therefore unanswered. On the other hand, no significant association was seen between PPD and type/outcome of delivery between the two groups of subjects. About this issue, our work confirmed once again the very high percentage of caesarean delivery performed in South of Italy[43,44].

Our work presents some limitations. First of all, we included all CD patients on GFD in our study; the full compliance to GFD was confirmed by the negative level of anti-transglutaminase antibodies in all CD patients. We decided to exclude patients with new/recent diagnosis of CD (who would be patients on free diet) because the majority of patients followed-up at our Centre consisted of individuals with previous diagnosis of CD and already on GFD. Hence, in order to recruit a homogenous population to the study, we decided to exclude patients who had recently been diagnosed with CD and were on free diet. However, thanks to the composition of our sample, we were able to document that PPD in patients suffering from CD is not directly related to active gluten ingestion. Further studies (ideally multicentre) are needed to define the prevalence of PPD in CD women on free diet (e.g., diagnosed with CD during their pregnancy or immediately after childbirth).

We used healthy subjects as control group. This methodological approach is necessary to demonstrate the real increase of PPD in patients with CD compared to the general population; however, it does not determine whether the high prevalence of PPD is related to CD specifically or to a non-specific “illness status”. In effect, as mentioned earlier[32], adults affected by CD do not differ substantially in terms of incidence of depression from those with other types of physical illness and the same could be true of PPD. In view of this, only a study directly comparing prevalence of PPD in patients with CD with that in patients suffering from other diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel diseases, rheumatologic diseases) could clarify this aspect.

However, the high prevalence of PPD in patients suffering from CD and the clinical relevance of this psychiatric condition justify the routine use of the EPDS questionnaire in women with CD who have recently given birth.

In conclusion, post-partum depression is a frequent condition in women affected by CD on GFD, particularly in those with history of menstrual disorders. We suggest screening for PPD in all women with CD for early detection and prompt treatment of this condition.

Many thanks to Giovanna Affinito, our nurse of endoscopy, for her precious support and contribution. Many thanks to Dr Sara Donetto (King’s College London - National Nursing Research Unit) for her unique technical and intellectual support.

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune enteropathy gluten-related, characterized not only by gastrointestinal symptoms, but also by an increased prevalence of psychological symptoms and mental disorders, specially depression, anxiety and sleep disorders.

Focused data on post-partum depression (PPD) in celiac women are still lacking.

In this case-control study, the authors evaluate, for the first time in the literature, the prevalence of PPD in CD patients on gluten-free diet compared to that of healthy subjects experiencing a recent delivery.

The authors demonstrated that PPD was present in 47.1% of CD women and in 14.3% of controls (P < 0.01; OR = 3.3). In the CD population the occurrence of PPD was significantly correlated with the presence of previous menstrual disorders. The authors suggest screening for PPD in all women with CD experiencing delivery for early detection and prompt treatment of this condition.

PPD is a psychiatric disorder affecting women after pregnancy and leading to disruptions in maternal-infant interactions, and lower cognitive functioning and behavioural problems in children.

In this manuscript, the authors present psychiatric disorders - showing higher incidence of PPD in patients with CD in comparison to healthy women controls. From the gastrological point of view this is a well written paper, but it should be evaluated by a psychiatrist to assess accuracy of psychological tests used for the assessment of depression.

P- Reviewer: Chiarioni G, Owczarek D S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, Biagi F, Fasano A, Green PH, Hadjivassiliou M, Kaukinen K, Kelly CP, Leonard JN. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013;62:43-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1254] [Cited by in RCA: 1157] [Article Influence: 96.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, Fabiani E, Heier M, McMillan S, Murray L, Metzger MH, Gasparin M, Bravi E. The prevalence of celiac disease in Europe: results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Ann Med. 2010;42:587-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Addolorato G, Leggio L, D’Angelo C, Mirijello A, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Abenavoli L, Leso V, Nesci A. Affective and psychiatric disorders in celiac disease. Dig Dis. 2008;26:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Addolorato G, Stefanini GF, Capristo E, Caputo F, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Anxiety and depression in adult untreated celiac subjects and in patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease: a personality “trait” or a reactive illness? Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1513-1517. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ciacci C, Iavarone A, Mazzacca G, De Rosa A. Depressive symptoms in adult coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:247-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Siniscalchi M, Iovino P, Tortora R, Forestiero S, Somma A, Capuano L, Franzese MD, Sabbatini F, Ciacci C. Fatigue in adult coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:489-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Addolorato G, Capristo E, Ghittoni G, Valeri C, Mascianà R, Ancona C, Gasbarrini G. Anxiety but not depression decreases in coeliac patients after one-year gluten-free diet: a longitudinal study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:502-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zingone F, Siniscalchi M, Capone P, Tortora R, Andreozzi P, Capone E, Ciacci C. The quality of sleep in patients with coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1031-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hewitt C, Gilbody S, Brealey S, Paulden M, Palmer S, Mann R, Green J, Morrell J, Barkham M, Light K. Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: an integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1-145, 147-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression – a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:37-54. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2085] [Cited by in RCA: 1888] [Article Influence: 118.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Blackmore ER, Carroll J, Reid A, Biringer A, Glazier RH, Midmer D, Permaul JA, Stewart DE. The use of the Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) tool in the detection of psychosocial risk factors for postpartum depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28:873-878. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wilson LM, Reid AJ, Midmer DK, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Stewart DE. Antenatal psychosocial risk factors associated with adverse postpartum family outcomes. CMAJ. 1996;154:785-799. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Beck CT. A meta-analysis of predictors of postpartum depression. Nurs Res. 1996;45:297-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Demyttenaere K, Lenaerts H, Nijs P, Van Assche FA. Individual coping style and psychological attitudes during pregnancy and predict depression levels during pregnancy and during postpartum. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:95-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moss KM, Skouteris H, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Milgrom J. Depressive and anxiety symptoms through late pregnancy and the first year post birth: an examination of prospective relationships. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yawn BP, Olson AL, Bertram S, Pace W, Wollan P, Dietrich AJ. Postpartum Depression: Screening, Diagnosis, and Management Programs 2000 through 2010. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:363964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peindl KS, Wisner KL, Hanusa BH. Identifying depression in the first postpartum year: guidelines for office-based screening and referral. J Affect Disord. 2004;80:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8260] [Cited by in RCA: 9439] [Article Influence: 248.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hanusa BH, Scholle SH, Haskett RF, Spadaro K, Wisner KL. Screening for depression in the postpartum period: a comparison of three instruments. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:585-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pitanupong J, Liabsuetrakul T, Vittayanont A. Validation of the Thai Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for screening postpartum depression. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM. Clinical practice. Postpartum depression. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:194-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Garcia-Esteve L, Ascaso C, Ojuel J, Navarro P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Spanish mothers. J Affect Disord. 2003;75:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Deligeoroglou E, Creatsas G. Menstrual disorders. Endocr Dev. 2012;22:160-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Iglesias EA, Coupey SM. Menstrual cycle abnormalities: diagnosis and management. Adolesc Med. 1999;10:255-273. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Riddle DL, Lee KT, Stratford PW. Use of SF-36 and SF-12 health status measures: a quantitative comparison for groups versus individual patients. Med Care. 2001;39:867-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center 1994; . |

| 28. | Ware JE. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3130-3139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2485] [Cited by in RCA: 2862] [Article Influence: 114.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zingone F, Iavarone A, Tortora R, Imperatore N, Pellegrini L, Russo T, Dorn SD, Ciacci C. The Italian translation of the celiac disease-specific quality of life scale in celiac patients on gluten free diet. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:115-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Benvenuti P, Ferrara M, Niccolai C, Valoriani V, Cox JL. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation for an Italian sample. J Affect Disord. 1999;53:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Beck CT, Gable RK. Postpartum Depression Screening Scale: development and psychometric testing. Nurs Res. 2000;49:272-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Smith DF, Gerdes LU. Meta-analysis on anxiety and depression in adult celiac disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:189-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yonkers KA, Vigod S, Ross LE. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of mood disorders in pregnant and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:961-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Johnston SD, Rodgers C, Watson RG. Quality of life in screen-detected and typical coeliac disease and the effect of excluding dietary gluten. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1281-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hannestad J, DellaGioia N, Bloch M. The effect of antidepressant medication treatment on serum levels of inflammatory cytokines: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2452-2459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 632] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Raedler TJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in major depressive disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:519-525. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Bloch M, Daly RC, Rubinow DR. Endocrine factors in the etiology of postpartum depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:234-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bloch M, Rotenberg N, Koren D, Klein E. Risk factors for early postpartum depressive symptoms. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Buttner MM, Mott SL, Pearlstein T, Stuart S, Zlotnick C, O’Hara MW. Examination of premenstrual symptoms as a risk factor for depression in postpartum women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Soni S, Badawy SZ. Celiac disease and its effect on human reproduction: a review. J Reprod Med. 2010;55:3-8. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Ciacci C, Tortora R, Scudiero O, Di Fiore R, Salvatore F, Castaldo G. Early pregnancy loss in celiac women: The role of genetic markers of thrombophilia. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:717-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Collin P, Vilska S, Heinonen PK, Hällström O, Pikkarainen P. Infertility and coeliac disease. Gut. 1996;39:382-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Guarino C, Sansone M. How to decrease the number of caesarean sections in Italy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24 Suppl 1:114-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Official Bulletin of Regione Campania. Indications for caesarean section. B.U.R.C. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center 2005; Available from: http://www.sito.regione.campania.it/burc/pdf05/burc20or_05/del118_05allegato.pdf. |