SEARCH STRATEGY

Data for this review were collected from our previous studies and experiences plus various data banks, such as PubMed, EMBASE, ISI Web of science, Scopus, Google Scholar and Iranian databases including Iranmedex and SID. A comprehensive search was performed using the combinations of the keywords “Hepatitis B, pregnancy, prenatal transmission, vaccination, treatment” to review relevant literature and higher education journals. The searches were done by using Boolean operators OR, AND between main phrase and the mentioned keywords were extracted from specific themes of the topic under study. A search strategy was built, applying the advanced search capability of the search engine. The inclusion criteria as set out was that only articles that explicitly dealt with Hepatitis B in pregnancy were included. We also looked at the reference list of the retrieved papers and searched other search engines. A total of 150 articles were found in the primary search but after elimination of duplicates or irrelevant papers, only 60 records were reviewed. All published data from 1999 to 2014 have been included in this review.

RESULT

Natural history of HBV

HBV can exist in many body fluids such as blood, saliva, semen and vaginal fluid. The virus can survive outside the body for more than 7 d. So, if scratched skin is in contact with an infected surface, infection occurs. When hepatitis B infection occurs, the patient enters the incubation period which is asymptomatic and the patient is usually unaware of the infection. During this period, liver transaminases are normal. Although the factors that affect the length of the incubation period are perhaps unknown, probably factors such as the size of HBV, the binding ability of cell surface receptors to the virus and the host immune system are involved. The incubation period may be as long as 2 to 6 mo with an average of 60 d[10]. The clinical appearance of hepatitis B infection varies depending on the age and the host immune system. Children under 5 years and adults with weakened immune systems are asymptomatic. Only 30% of people with acute infection will develop jaundice. Jaundice may be mild or severe, depending on the host’s immune system. The final phase of chronic HBV infection is recovery, in which transaminases are decreased and the clinical signs are lowered. Viral hepatitis is an inflammatory widespread phenomenon which can cause acute or chronic liver damage. The main mechanisms of hepatocyte injury are unclear although specific and nonspecific antigens are involved in hepatocyte injury. Evidence suggests that the characteristics and clinical outcomes after acute liver injury are associated with viral hepatitis and are determined by immunological responses of the host. Outcome of HBV infection varies from full recovery to progression to chronic hepatitis and death from fulminant hepatitis is rarely seen[11-13].

Natural history of HBV in pregnancy

In areas of high prevalence, most patients with chronic HBV are women of reproductive age[14]. Transmission from mother to fetus during prenatal or horizontal transmission in childhood are the main ways of transmission of HBV in areas with a high and moderate prevalence. Also, in areas with low prevalence, unsafe sexual activity is the most common way of transmission[15]. Therefore, women of reproductive age are considered an important source of infection[16]. Risk factors for chronic HBV carriers in the reproductive age population are unknown. The factors associated with chronic carrier status include resident status, positive family history, no history of previous vaccination and previous hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) testing[17]. Chronic HBV infection is likely to be a significant cause of infertility. HBV infection reduces fertilization ability during in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer[18]. The clinical course of HBV infection does not change during pregnancy and usually there is no difference in pregnant and nonpregnant women. It has been identified that hepatitis flares occur rarely during pregnancy, while its indices increase after delivery. There are controversies regarding the disease complications in pregnant women and fetuses. Some believe that chronic carriers of HBV in pregnancy are associated with increased rates of miscarriage, gestational diabetes and preterm labor[19]. The assessment of fetal distress in pregnant women with HBV showed that HBV infection can cause chorion angiopathy and decrease placental function, leading to fetal distress[20]. Available information indicates that HBV transmission via the placenta is not as common as previously thought; actually, viral DNA is rarely found in amniotic fluid or cord blood[3]. Most infant infection in the womb is caused by the mother’s blood transfusion to the fetus during uterine contractions or rupture of fetal membranes[8] or by vertical transmission perinatally by exposure to blood or secretions of an infected birth canal of the mother[21]. It is estimated that 50% of cases of chronic hepatitis B are results of vertical transmission or acquired in early childhood[8]. The mechanisms through which HBV infections are transmitted in the uterus are controversial and being reviewed. Some of these assumptions include transmission through the placenta, transfer through placental leakage, cracks in the placental barrier, mononuclear cells in peripheral blood and transmission through the father[22]. Intrauterine transmission of HBV infection occurs via two pathways: (1) blood release (hematogenous) that causes the infection of placental vascular endothelial cells and is probably the main route for infection transmission; and (2) cellular transport through cell by cell. One of the explained mechanisms of the intracellular transport route is binding of HBsAg-anti-HBsAb with Fc-γ receptor III[10].

A study of 402 infants of HBsAg-positive mothers showed that the risk of intrauterine transmission depended on HBeAg-positive mothers and virus existence in vascular endothelial cells in chorionic villi[23]. The most important risk factors for mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) include: HBV DNA > 200000 IU (106 copies)/mL, HBeAg positive and pregnancy complications such as preterm delivery, prolonged labor and prior failure of immunoprophylaxis in sibling(s). Antiviral therapy in the last stages of pregnancy is the most effective way to reduce transmission of infection from the mother. Besides, elective cesarean delivery can reduce the risk of transmission[24]. The prevalence of HBV infection in infants and children are different depending on race and ethnicity, with Asian women having the highest prevalence (6%)[25].

MTCT

Hepatitis B virus can be integrated in the placenta, leading to the infection. In Wang’s study of 15 HBeAg-positive mothers and their babies, he revealed that HBeAg actually crosses the human placenta. In the case of simultaneous TORCH (Toxoplasmosis, Other Agents, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes Simplex) infections that can cause placental cracks or a damaged placental barrier, neonatal HBV infection further increases. Also, HIV infection increases the risk of transmission of HBV infection[26]. In another study, Elefsiniotis et al[27] examined serological and virological profiles of cord blood samples taken from mothers with negative HBeAg and revealed that in almost a third of these mothers, HBsAg, despite maternal viral load, HBV pathology and type of delivery, can pass through placental barrier. Chronic HBV in pregnant women is usually mild but the disease may flare up shortly after birth[28]. HbsAg-positive mothers that are also HbeAg-positive are more likely to transmit the disease to their infants (70% to 90%), while the HbsAg-positive and HbeAg-negative mothers have a lower infection transmission rate[21]. The risk of transmission in HbeAg-negative mothers is 10% to 40% and in affected infants, 40% to 70% of the infection becomes chronic[25].

Although infection in HbeAg-negative mothers occurs less commonly, infants in early periods of infancy often progress to acute or fulminant hepatitis. So, despite the HBeAg/Ab status of the mothers, prevention in infants is necessary[29]. The transmission rate in pregnant women with a positive serum viral DNA is 90%, while for pregnant women with negative viral DNA it was reported to be 10% to 30%[30,31]. Hepatitis B vaccine is safe for pregnant women in each trimester and those who are seronegative can be vaccinated during pregnancy. Serum level protection in pregnant women is only 45%. This is lower than that mentioned for nonpregnant women as well as for women during the postpartum period that had received three doses of the vaccine[32]. Vaccination during pregnancy, in addition to being beneficial for the mother, also provides partial immunity for the infant[33]. Studies showed that a maternal prenatal screening program and active and passive immunization of infants after delivery significantly decreased HBV infection to 95%[34]. Most infections of pregnant women are chronic and asymptomatic and are diagnosed in prenatal screening. These women are considered to have chronic hepatitis but antiviral therapy is generally not performed during pregnancy[3]. Perinatal HBV transmission accounts for about 21% of HBV-related deaths worldwide and 13%-26% regionally[35]. HBsAg was found to be positive in 50% of cord blood and 95% of gastric fluid samples of infants of HbsAg-positive mothers. During labor, the infant is in contact with the mother’s blood which contains the virus and it is possible for him to swallow contaminated fluids, enabling neonatal infection by physiological transfusion or blood contact and the mother’s birth canal secretions[10,36].

Global hepatitis B disease burden and impact of vaccination

Safe and effective vaccines have been available to prevent HBV infection since 1981 and the cost-effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination has been well documented[37]. A study performed in Iran by Alavian[38] showed a significant reduction in the rate of HBsAg positivity in the subgroup of children aged 2-14 years after expanding the immunization program. HB vaccine can be fully justified on economic grounds in that either the cost-benefit ratio is positive or the cost-effectiveness ratio suggests the vaccine to be a good “buy” for the public health services or both[38]. Several studies have implicated high maternal viremia as the most important factor associated with failure of neonatal vaccination[39]. The key strategy to decrease mortality from HBV is to prevent infants from acquiring HBV infection. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all newborns receive their first HB vaccination before hospital discharge[2]. For infants born to HBV-infected women, administering ACIP-recommended post-exposure prophylaxis of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and HB within hours of birth followed by completion of the HB series has been shown to be 85%-95% effective in preventing HBV infection[40] .

From a few reported trials, HB vaccine and HBIG seem safe. Furthermore, cohort studies found that HB vaccination is well tolerated and that severe adverse events are rare[21]. One systematic review showed that HB vaccine, HBIG and vaccine plus immunoglobulin prevent hepatitis B occurrence in infants of mothers positive for HBsAg[21]. In a follow up study of 184 infants born to HBsAg carrier mothers, Wang et al[41] found that after infants were immunized by HBIG combining HB vaccine, the anti-HBs-positive rate reached 92% at 7 mo and gradually decreased thereafter. 72.04% of the infants at 24 mo and 60% at 36 mo showed detectable levels of anti-HBs[41]. Cost effectiveness studies showed that in countries with low, intermediate and high HBV prevalence, vaccination of infants of HbsAg-positive mothers had numerous advantages[21]. Infants who are infected with hepatitis B are generally asymptomatic but 90% of them develop chronic infection[42]. Coadministration of specific immunoglobulin and HB vaccine is highly effective in preventing infection. However, approximately 10% to 20% of infants are still chronically infected despite receiving this treatment in their early life. Intrauterine infection is the leading cause of HB vaccine failure in infants born to mothers with HBV[34].

Without immunoprophylaxis, up to 90% of infants born to HBeAg-positive mothers become HBV carriers. In comparison, 20% to 30% of children infected between the age of 1 to 5 years and fewer than 5% of immunocompetent adults become HBV carriers[43]. Intrauterine HBV infection has been suggested to be caused by transplacental transmission that cannot be blocked by the HB vaccine[23]. In a case-control study of 402 HBs Ag-positive pregnant women in China, Xu et al[23] found that 3.7% of their newborn were HBs Ag positive within 24 h of birth. The main risk factors for intrauterine HBV infection were maternal serum HBeAg positivity, history of threatened preterm labor and HBV in villous capillary endothelial cells in the placenta.

Joint immunoprophylaxis with HBIG and three doses of HB vaccines to infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers are known to be safe and effective. However, 5%-10% of infants of HBV-positive mothers become infected even with proper vaccination[21]. There are some cases of vaccination failure. Very high maternal viremia, intrauterine infection or escape mutants after the implementation of the universal vaccination program are possible reasons for vaccination failure. Immunocompromised hosts also risk vaccination failure[7]. Hence, health care providers must consider the maternal HBV DNA level in decision making regarding management options during pregnancy[25].

Treatment of HBV during pregnancy

HBV treatment in pregnancy is complicated[43]. For women with HBV who have intentions of becoming pregnant, treatment can be postponed in cases of mild disease until after delivery. In cases of moderate or severe disease or getting pregnant during treatment, it is necessary that the potential risks of treatment with antiviral drugs be evaluated against the risk of disease progression in the case of no treatment[19]. Pregnant women with low viral loads do not need immediate treatment, while for severely viral mothers (> 109 copies/mL), antiretroviral therapy in the last trimester of pregnancy should be considered[44]. Management of HBV treatment in pregnancy is unique. Aspects of care and treatment that need to be taken into consideration include: HBV effects on pregnancy; pregnancy effects on HBV and its complications; HBV treatment during pregnancy; and prevention of perinatal HBV infection[28]. Zhang et al[45] assessed the effects of telbivudine on HBV intrauterine infection during the last phases of pregnancy in 61 pregnant women and found that serum HBV DNA levels in patients treated with telbivudine were significantly lower than the control group (P < 0.01). Infection rate was reported to be 0% in infants receiving telbivudine and 13.3% in the control group. These researchers stated that treatment of HBV-infected mothers with telbivudine can block intrauterine infection[45].

Another study evaluating the effectiveness and safety of using HBIG during pregnancy to prevent mother to child transmission showed that infants of mothers receiving HBIG were less infected by intrauterine infection (indicated by HBsAg as OR = 0.22; indicated by HBV DNA as OR = 0.15; P < 0.01 for both) and a high level of safety and protection was observed in them (indicated by HBs Ab as OR = 11.79; P < 0.01)[46]. A randomized trial on interrupted HBV intrauterine transmission estimated that repeated HBIG injections to pregnant women before the delivery may block the HBV intrauterine infection by reducing the level of viremia[34]. Numerous studies reported that treatment with lamivudine in highly viral pregnant women prevents HBV replication. In the recent study, lamivudine (100 mg/d) therapy was administered to pregnant patients with HBV who had levels of HBV DNA greater than 10000 copies/mL after the 32nd gestational week. A 102 decrease in HBV viral load was observed in 71% of the patients[47].

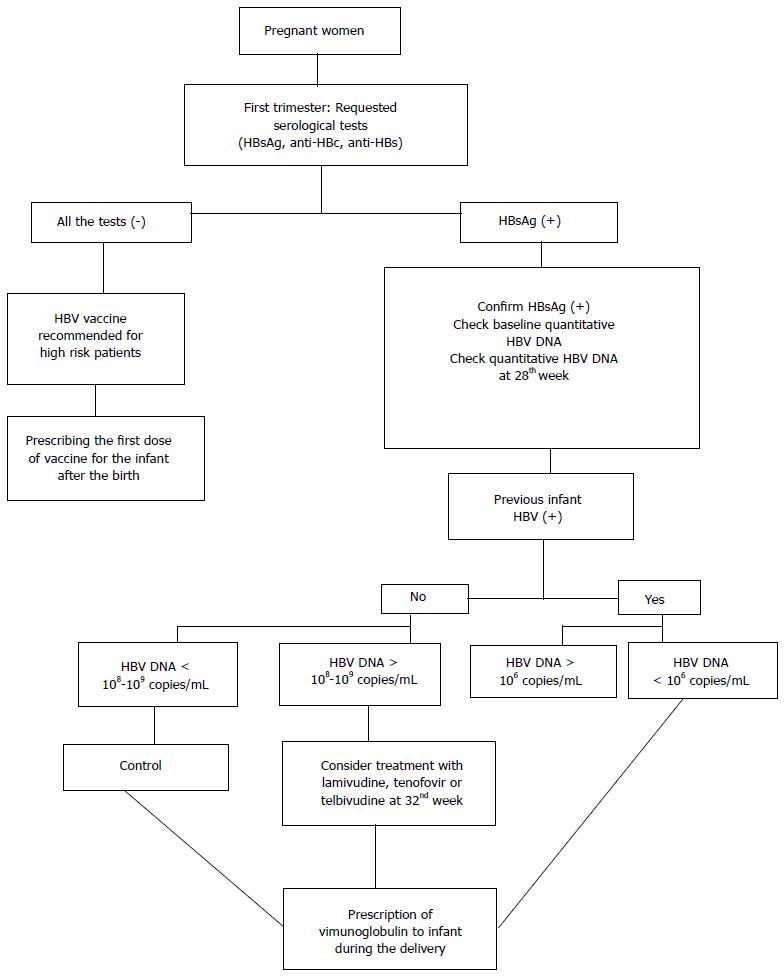

Safety of medications used during pregnancy and lactation, the effect of the chosen drug, resistance to treatment, side effects and duration of the treatment are factors that should be considered in the treatment of pregnant women with hepatitis B. If delivery takes place in the near future, it is wise to delay treatment until after the delivery[48,49]. In women at high risk or with known HBV infection who want to be pregnant, it is necessary to determine the exact status of the disease so that an appropriate treatment plan can be scheduled. A therapeutic approach to hepatitis B during pregnancy involves three basic strategies as follows: (1) screening pregnant women and performing a routine HBsAg test at the first prenatal visit; (2) treatment of HBV infection in pregnant women; and (3) prevention of mother-infant transmission[3,25] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Hepatitis B virus treatment algorithm during pregnancy[43,44,50].

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBc: Hepatitis B core antigen.

Counseling and prenatal care in hepatitis B

Since health status during pregnancy depends on the health status before it, pre-pregnancy counseling and care of patients with hepatitis should be an essential part of the patient’s training. A comprehensive plan of care before pregnancy can help in reducing the risks, promoting healthy life styles and increasing preparation for pregnancy. Principles of pre-pregnancy counseling should include the following[51]: (1) high risk women should be screened and can be vaccinated against hepatitis B[52]; (2) the test for hepatitis B has been confirmed to be negative before starting the anonymous donor oocyte in vitro fertilization sequence[53]; (3) infected women should be counseled regarding the risks of the disease and transmission; (4) patients with hepatitis B should be referred for treatment before becoming pregnant; (5) before starting treatment, request a β-hCG test for the patient to ensure she is not pregnant since some drugs used to treat hepatitis are teratogenic for the fetus; (6) explain about effective contraceptives to suit each individual ; and (7) remind women not to take oral contraception, because their estrogenic effects on the liver are unknown[32].

It is important to consider a comprehensive health care program that includes an integrated approach to medical and psychosocial care for pregnant women with hepatitis B. Accurate and detailed information should be obtained from the pregnant women regarding the history of previous delivery, using alcohol and drugs during pregnancy, serological hepatitis B test and immune status of the pregnant women. Monitoring the health status of the fetus and determining the next prenatal visits based on the patient’s condition are among the other prenatal care needed. Although nutrition knowledge attempts to identify the ideal amount of nutrition groups for pregnant women, people who are directly responsible for the care of mothers with hepatitis B can perform their duties in the best way[54-56].

Breast feeding and hepatitis B

Breastfeeding is the foundation of infant nutrition and sets the scene for lifetime health. The World Health Organization recommends that all mothers who are hepatitis B positive breastfeed their infants and that their infants be immunized at birth[57]. A recent meta-analysis review reported breastfeeding after proper immunoprophylaxis did not contribute to mother-to-child transmission of HBV[58]. Mothers with hepatitis B are advised to pay attention and check the nipples before each feed and in case of any cracks, bleeding or any kind of blood on the nipples, to temporarily stop breastfeeding and express all the milk and discard it. When the nipples are healthy without any cracks, the milk should be expressed, kept in good condition and given to the infant at the time of cessation of breastfeeding. The mother should learn the correct way of breastfeeding and embracing the infant so that an uncomfortable position does not cause the infant to refuse breastfeeding. During teething, caution should be taken so that the nipple is not wounded and a milk bottle can be used at this time. To prevent mother to child transmission, the following actions are recommended: educate the mothers; isolate HbsAg-positive mothers during labor; clean blood and secretions from the infant’s body; and active and passive immunization of infants soon after birth[59,60].