Published online Aug 10, 2014. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v3.i3.118

Revised: May 9, 2014

Accepted: July 25, 2014

Published online: August 10, 2014

Processing time: 172 Days and 8 Hours

Worldwide women have to cope up with heavy burden of unwanted pregnancies, mistimed, unplanned, with risk to their health. Their children and families also suffer. Such pregnancies are root cause of induced abortions (safe/unsafe) and grave consequences. Women, their partners can, for most part, prevent unwanted pregnancies by using contraceptives. However many women either do not use any contraceptive or use methods, with high failure rates. These women account for 82% of pregnancies that are not desired. Remaining unintended pregnancies occur among women who use modern contraceptive, either because they had difficulty using method consistently or because of failure. Helping women, their partner use modern contraceptives effectively is essential in achieving Millennium Development Goals for improving women’s health, reducing poverty. If all women in developing countries use modern contraceptives, there would be 22 million less unplanned births, 25 million fewer induced, 15 million fewer unsafe abortions, 90000 less maternal deaths and 390000 less children losing their mothers. Also making abortion services broadly legal, by understanding size, type of unmet needs, most important by creating awareness in communities can surely help tackle this problem to a large extent.

Core tip: Unintended pregnancies are the root cause of induced abortions, both safe and unsafe, and their grave consequences all over the world. The high rates of unintended pregnancies all over the world are due to many reasons, including unmet needs of modern contraceptives. This article throws light on issues of unmet needs of contraception, unintended births their consequences and rates of unsafe abortions and their reasons all over the world.

- Citation: Chhabra S, Kumar N. Unwanted pregnancies, unwanted births, consequences and unmet needs. World J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 3(3): 118-123

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v3/i3/118.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v3.i3.118

In 2008, two hundred and eight million pregnancies occurred worldwide, out of which 102 million resulted in intended births (49%), 42 in induced abortions (20%) (22 legal and 20 unsafe)[1], 33 (16%) in unintended births and 31 (15%) in miscarriages[2]. Singh[3] reports, around 86 million unintended pregnancies occurring each year with grave consequences, unsafe abortions which lead to disabilities and deaths, stillbirths, neonatal deaths[4,5] affecting families, nations, particularly in low/middle income countries[1,6]. Such pregnancies slow the progress towards socioeconomic development, lead to population growth, difficulties in providing education for all and eradication of extreme poverty and hunger.

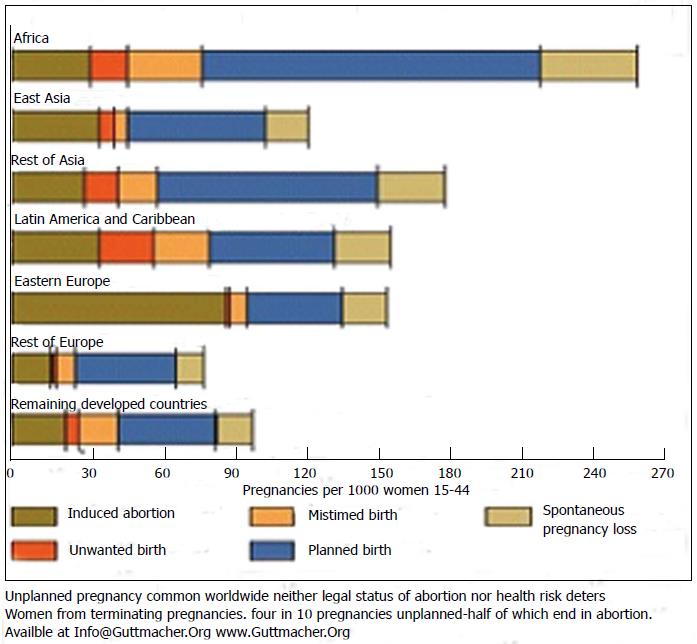

Of developed countries, the United States has the highest unintended pregnancy rates, including in teens[7]. Worldwide 40% of pregnancies among white women, 67% blacks, 53% Hispanics[8] and 48% among Southeast Asian are unintended[9]. Each year, 2.7 million unintended pregnancies occur in young women in Southeast Asia[9]. Worldwide between 1995-2003, the overall abortion rate dropped from 35 to 29, but remained virtually unchanged at 28, in 2008[1]. Overall, pregnancy rates are higher in developing world than in developed countries[3,10] (Figure 1). In India annually 78% conceptions are unplanned and 25 % unwanted. The abortion rates are strikingly similar for developed and developing countries, however close to half of abortions are unsafe, (98% from developing countries)[11]. Indian Council of Medical Research, reported 13.5 illegal abortions per 1000 pregnancies[12]. Given that abortions taking place at registered facilities are grossly under-reported in India[13-17], figures represent only tip of the iceberg. Many studies reveal 3.4-14.0 induced abortions per 100 live births[14,18]. According to NFHS-3, India has 13.2% unmet need for contraception, 50 % for spacing methods[19].

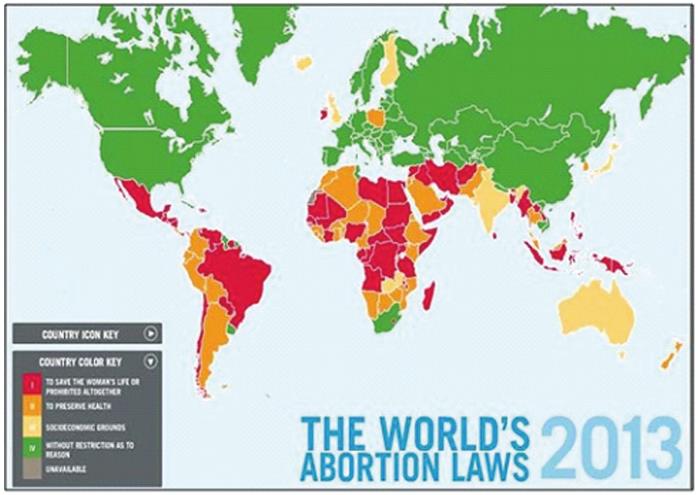

Worldwide, 60% of women of reproductive age (15-44) live in countries where abortion is broadly legal[20] and remaining 40%, almost entirely in the developing world where abortion is highly restricted[21]. Globally, laws are varied based on grounds for which abortion is permitted, range from no grounds or to save a woman’s life, to preserve physical health or mental health or rape or incest, in cases with fetal impairment or even for economic or social reasons, and without restriction. In 32 countries, abortion is not legally permitted on any grounds and in 36 countries, it is permitted when a woman’s life is threatened. A further 59 countries allow abortion to save a woman’s life, to preserve her physical health, and to protect her mental health. Fourteen countries, including India, permit on all the above and also socioeconomic grounds. A total of 56 countries and territories allow it without restriction[22] (Figure 2). There has been effect of issues like Global Gag, under which agencies receiving USAID funds are prohibited from performing or campaigning for abortion. Contrary to its stated intentions, the global gag rule resulted in more unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and female deaths[23]. Moreover, some laws seek to protect or otherwise recognize the fetus as human. The American Convention on Human Rights, a treaty signed by 24 Latin American countries states that from the moment of conception, human beings have rights[24].

The reasons cited for choosing abortion are broadly similar globally. Although official records in India show contraceptive failure and risk to mother’s health as leading reasons[25], reliability of these records, for obvious reasons can be questioned. Where effective contraceptive methods are available and widely used, the rates decline sharply, but nowhere to zero[26].

Many women and men either do not have access to appropriate contraceptive methods, or lack adequate information and support to use them effectively. Studies have examined the reasons why some women do not use contraception, though they do not want to become pregnant, referred to as unmet need for family planning[27-29]. Study by Alan Guttmacher Institute[30] reveals that 54% women who had abortion had used contraception during the month they became pregnant, however 76% pill users, 49% condom users reported having used methods improperly, 13% pill users, 14% condom users reported correct use, 46% of women had not used any contraceptive during the months they became pregnant. Of these, 33% had perceived themselves to be at low risk for pregnancy, 32% had concerns about methods, 26% had unexpected sex and 1% had been forced to have sex. Trussell and United Nations Population Division have also reported contraceptive failure rates with estimated unintended pregnancies (Table 1)[31].

| Contraceptivemethod | Number ofcontraceptive users 000 s | Estimated failure rate (typical use) % | Number of women with accidental pregnancies (typical use) 000 s |

| Female sterilization | 232564 | 0.50 | 1163 |

| Male sterilization | 32078 | 0.15 | 48 |

| Injectables | 42389 | 0.30 | 127 |

| IUD | 162680 | 0.80 | 1301 |

| Pill | 100816 | 5.00 | 5041 |

| Male condom | 69884 | 14.00 | 9784 |

| Vaginal barrier | 2291 | 20.00 | 458 |

| Periodic abstinence | 37806 | 25.00 | 9452 |

| Withdrawal | 32078 | 19.00 | 6095 |

| Total | 712586 | 4.70 | 3369 |

Studies reveal that unwanted pregnancies and induced abortions due to contraceptive failure were 48% and 54% in United States[32] and 65% unwanted pregnancies in France respectively[33]. Proportions are more in countries with higher levels of contraceptive use.

About one third of women who undergo abortion, experience serious complications, but less than half receive appropriate medical care. Currently, about 8.5 million women globally suffer from complications of unsafe abortions annually and 3 million remain without treatment[3]. World Health Organization[21] reports that 47000 women died worldwide in 2008 and around 13% pregnancy related deaths were due to unsafe abortions[34]. Annually in Asia, 12% maternal deaths are due to unsafe abortions[21]. Mortality represents only a fraction of abortion related complications, as many more experience life threatening and other morbidities[35,36]. An estimated 7.4 million disability-adjusted life years are lost annually as a result of unsafe abortion[6]. Each year 1.6 million women have secondary infertility and 3-5 million suffer from chronic reproductive tract infections. Rarely bowel injuries can also occur. Agarwal et al[37] has reported an unusual case of bowel injury 52 d after induced abortion.

Though most of morbidity and mortality are preventable, yet millions of women suffer due to unavailability of treatment in health care system. So the concept of Post Abortion Care has become visible, a global approach for prevention. The essential elements include: emergency treatment of potentially life-threatening complications, contraceptive counseling services and linkage to other emergency services[38].

Unmet needs are global, which look at issues related to the family planning needs of reproductive population in a quantifiable mode for prevention of pregnancy or birth or consequences, in currently married women who do not want any more children or who want to postpone their next birth, but are not using any form of family planning[28]. Conventional estimates of unmet need include only married women, but sexually active unmarried, especially teenagers, those with postpartum amenorrhea, using a less effective contraceptive method or using an effective method incorrectly, or dissatisfied, or with contraindications to its use, with unwanted births without access to safe and affordable abortion services; and those with related reproductive health problems, also need to be included.

A recent study revealed that in 2010 worldwide, 146 million (130-166 million) women aged 15-49 years who were married or in a union had an unmet need for family planning. The absolute number is projected to grow from 900 million (876-922 million) in 2010 to 962 million (927-992 million) in 2015, and will increase in most developing countries[39]. The uptake of modern contraceptive methods worldwide has slowed in recent years, from an increase of 0.6% points per year in 1990-1999 to an increase of only 0.1% points per year in 2000-2009. In Africa, the annual increase in modern contraceptive use fell from 0.8% points in 1990-1999 to 0.2% points in 2000-2009[40]. Demographic Health survey (2000-2009) has revealed unmet need, met need and total demand for family planning (Table 2).

| Region/Country | Unmet need for spacingA | Unmet need for limitingB | Unmet needTotalC = (A + B) | Met need(CPR)D | Total demand for family planning E = (C + D) | Percentage of demand satisfied F = (D/E) |

| East Asia and Pacific | 6 | 8 | 14 | 57 | 71 | 79 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 4 | 9 | 13 | 60 | 73 | 83 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 7 | 10 | 17 | 63 | 80 | 77 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 4 | 7 | 11 | 57 | 68 | 84 |

| South Asia | 8 | 12 | 20 | 47 | 67 | 70 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 17 | 9 | 26 | 25 | 51 | 45 |

The causes of unmet needs are complex. Surveys and other indepth research from 1990s[41,42] reveal a range of obstacles and constraints that can undermine a woman’s ability to act on her childbearing preferences. In the developing world, her reasons for not using contraceptives most commonly include concerns about possible side-effects, the belief that they are not at risk of getting pregnant, poor access to family planning, their partner’s opposition to contraception or their own opposition because of religious or personal reasons. Other less common reasons are lack of knowledge about contraceptive methods or health concerns. Thirteen surveys completed in 1999 and 2000 by DHS revealed similar findings[43].

Education is an important determinant of unmet need for contraception. Both husband’s and wife’s education affect unmet need for spacing. As per a study in Ethopia[44] about one in five women (18.9% in 2000 and, 20.5% in 2005) with no education had unmet need for spacing, while 11.6% in 2000 and 14.8% in 2005 had unmet need for limiting. Unmet need progressively declined with higher levels of women’s education.

Religion has a strong influence on sexuality and abortion practices. A study revealed that most Buddists believe that conception occurs when the egg is fertilized, emergency contraception could prevent a fertilized egg from implantation. It therefore is against religion as they see abortion as an act of killing[45]. Catholics believe in using natural methods of contraception rather than modern and are strictly against abortion. According to them “Human life must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception¡.. Abortion is gravely contrary to the moral law¡.”[46]. In Hinduism contraception and abortion are not strictly prohibited, there are varying views. In Islam all forms of contraception are acceptable in special circumstances and abortion is permitted if mother’s life is at risk. Jewish law prohibits use of contraceptives in males, but there is no mention of females. In Sikhism there are no hard and fast rules for use of contraceptives and abortion. They can have it as and when required.

In each country, broader education and communication programs can help address social, cultural barriers and misconceptions. From a policy perspective, reducing unmet need is important for achieving both demographic goals and enhancing individual rights.

It is essential for nations to adopt a continuum of care, access to family planning, emergency contraception, and other reproductive-health services. It is essential to know why women choose abortion and how to reduce morbidity and mortality. Making abortion legal is an essential prerequisite in making it safe. Under the current scenario of high mortality and morbidity, medical means offer great potential for improving access and safety as it does not require extensive infrastructure and is non-invasive.

Not only treatment of complications of unsafe abortion should be extended throughout the health care system, family planning advice and assistance should be offered after treatment of complications; designed with women’s preferences in mind. Those wanting to prevent or postpone conception, using an ineffective method, those using an effective method incorrectly and those using an unsafe or unsuitable method[13,47]. Reducing unmet need is an effective way to prevent unintended pregnancies, abortions and births.

A key argument is that meeting unmet needs, saves lives, but to what extent does society value women’s lives?

P- Reviewer: Fett JD, Messinis IE, Tsikouras P, Xiu QZ S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization 2007; Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafeabortion_2003/ua_estimates03.pdf. |

| 2. | Sedgh G, Singh S, Shah IH, Ahman E, Henshaw SK, Bankole A. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 2012;379:625-632. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41:241-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Black KI, Gupta S, Rassi A, Kubba A. Why do women experience untimed pregnancies? A review of contraceptive failure rates. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;24:443-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bhutta ZA, Yakoob MY, Lawn JE, Rizvi A, Friberg IK, Weissman E, Buchmann E, Goldenberg RL. Stillbirths: what difference can we make and at what cost? Lancet. 2011;377:1523-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality 1990–2008: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010; (accessed 6 September 2010) Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241500265/en/index.html. |

| 7. | Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43:41-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84:478-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 924] [Cited by in RCA: 863] [Article Influence: 61.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guttmacher Institute. Facts on the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Adolescent Women in the Developing World (New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2010). Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/FB-Adolescents-SRH.pdf, on Feb.1, 2012. |

| 10. | Chandhick N, Dhillon BS, Kambo I, Saxena NC. Contraceptive knowledge, practices and utilization of services in the rural areas of India (an ICMR task force study). Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57:303-310. [PubMed] |

| 11. | World Health Organization (WHO) Safe abortion. Technical and policy guidance for health system. Geneva, WHO. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003; Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/safeabortion/SafeAbortion.pdf. |

| 12. | Chandhick N; ICMR. 2010. Estimates of maternal mortality ratios in India and its sates – a pilot study. Available from: http://icmr.nic.in/final/Final Pilot Report.pdf.Accessed 30 Nov 2010. |

| 13. | Khan ME, Barge S, Kumar N, Almroth S. Abortion in India: current situation and future challenges. Pachauri S and Subramaniam S. [eds]. Implementing a reproductive health agenda in india: the beginning. New Delhi: Population Council Regional Office 1999; 507-529. |

| 14. | Ganatra B. Abortion research in India: What we know, and what we need to know. In R. Ramasubban and SJ Jejeebhoy, eds. India: Women's Reproductive Health 2000; 186-235. |

| 15. | Jagannathan R. Relying on surveys to understand abortion behavior: some cautionary evidence. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1825-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lara D, Strickler J, Olavarrieta CD, and Ellertson C. Measuring Induced Abortion in Mexico. Sociological Methods & Researc. 2004;32:529-558. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Philipov D, Evgueni MA, Tatyana K, Vladimir MS. Induced Abortion in Russia: Recent Trends and Underreporting in Surveys. EUR J POP. 2004;20:95-117. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Malhotra A, Nyblade L, Parasuraman S, MacQuarrie K, Kashyap N. Realizing reproductive choicesand rights: abortion and contraception in India. Washington, D. C: International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) 2003; 35. |

| 19. | International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Marco International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-2006: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS. Available from: http://www.iipsindia.org. |

| 20. | Cohen SA. Facts and Consequences: Legality, Incidence, and Safety of Abortion Worldwide. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2009;12:2–6. |

| 21. | World Health Organisation. Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008 Sixth edition. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501118_eng.pdf. |

| 22. | Singh S, Darroch JE, Ashford LS, Vlassoff M. Adding It Up: The Costs and Benefits of Investing in Family Planning and Maternal and Newborn Health, New York: Guttmacher Institute and UNFPA 2009. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/media/nr/2010/11/16/index.html. |

| 23. | Ipas declines to sign the Global Gag Rule: public statement. Reprod Health Matters. 2001;9:206-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sood M, Juneja Y, Goyal U. Maternal mortality and morbidity associated with clandestine abortions. J Indian Med Assoc. 1995;93:77-79. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Duggal R, Ramachandran V. The Abortion Assessment Project-India: Key findings and recommendations. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12:122-129. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Westoff CF, Bankole A. Unmet need: 1990-1994. Calverton, Maryland, Macro International(DHS Comparative Studies No. 16, 1995). Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pub_details.cfm?ID=24. |

| 28. | Westoff CF. New Estimates of Unmet Need and the Demand for Family Planning (DHS Comparative Reports No. 14. Calverton, Maryland, USA. Macro International Inc. 2006). Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/CR14/CR14.pdf. Access February 22, 2010. |

| 29. | Sedgh G, Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S. Women with an Unmet Need for Contraception in Developing Countries and Their Reasons for Not Using a Method (Occasional Report No. 37). New York: Guttmacher Institute 2007; 5-40. |

| 30. | Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Contraceptive use among U.S. women having abortions in 2000-2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:294-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | United Nations Population Division. Department of Economic and Social Affairs ]World Contraceptive use 2007 (wallchart)]. New York: United Nations 2009; . |

| 32. | Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1277] [Cited by in RCA: 1116] [Article Influence: 58.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Moreau C, Trussell J, Rodriguez G, Bajos N, Bouyer J. Contraceptive failure rates in France: results from a population-based survey. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2422-2427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Haddad LB, Nour NM. Unsafe abortion: unnecessary maternal mortality. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2:122-126. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, Romero M, Ganatra B, Okonofua FE, Shah IH. Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic. Lancet. 2006;368:1908-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 450] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Singh S. Hospital admissions resulting from unsafe abortion: estimates from 13 developing countries. Lancet. 2006;368:1887-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Agarwal R, Radhika AG, Radhakrishnan G, Malik R. Faeces per vaginum: a combined gut and uterine complication of unsafe abortion. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2013;63:142-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Johnston HB. Abortion practice in India: a review of literature. Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT) 2002; 23. |

| 39. | Alkema L, Kantorova V, Menozzi C, Biddlecom A. National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1642-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | United Nations (UN). Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World contraceptive use. Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT) 2011; UN Population Division, 2011) Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/contraceptive2011/contraceptive2011.htm. |

| 41. | Khan S, Bradley S, Fishel J, Mishra V. 2008. Unmet Need and the Demand for Family Planning in Uganda: Further Analysis of the Uganda Demographic and Health Surveys, 1995– 2006; Macro International Inc) Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com. |

| 42. | Igwegbe A, Ugboaja J, Monago E. Prevalence and determinants of unmet need for family planning in Nnewi, South-east Nigeria. Int J Med Med Sci. 2009;1:325–329 Available from: http://www.academicjournals.org/familyplanningservices.Lastaccessed21/10/2010. |

| 43. | Westoff CF. Unmet Need at the End of the Century, DHS Comparative Reports No.1 (Calverton, MD: ORC Macro). Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com. |

| 44. | Hailemariam A, Haddis F. Factors affecting unmet need for family planning in southern nations, nationalities and peoples region, ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2011;21:77-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Your Guide to Emergency Contraception; London: FPA, 2011. . |

| 46. | Catechism of the Catholic Church: Revised in Accordance with the Official Latin Text Promulgated by Pope John Paul II. 2nd ed. Vatina City: Liberia Editrice Vaticana 1997; . |

| 47. | Johnston HB, Ved R, Lyall N, Agarwal K. Post-abortion Complications and their Management: Chapel Hill, NC: Intrah, PRIME II Project, 2001. (PRIME Technical Report #23). Available from: http://www.intrh.org. |