Published online Feb 10, 2014. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v3.i1.21

Revised: October 24, 2013

Accepted: November 2, 2013

Published online: February 10, 2014

Processing time: 140 Days and 17.6 Hours

The uterus is an uncommon site of metastasis especially from a primary lung adenocarcinoma. More frequently, extragenital primary tumours, including lung cancer, metastasize to the ovaries. In the literature, lung cancer metastasizing to the uterus is rare and has been reported to involve the endometrium and uterine serosa. Here, we report an unusual case of a 58-year-old woman who had a history of lung adenocarcinoma with subsequent metastasis to a single uterine fibroid only. The patient was known to have a long history of asymptomatic fibroids. In 2008, she was diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma which was treated with primary surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Four years later, a routine abdominal computerised tomography scan showed an enlargement of the fibroid and she underwent a hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Pathology reported a lung adenocarcinoma metastatic to the uterine leiomyoma with a similar morphology to the original pulmonary malignancy and this was confirmed with immunohistochemical staining. She had no evidence of metastatic disease elsewhere. The final diagnosis was metastasis of a primary lung adenocarcinoma confined to a uterine leiomyoma. Our patient also fulfilled the criteria for a phenomenon called tumour-to-tumour metastasis in this case a primary malignancy having metastasized to a benign tumour. In conclusion, metastasis of a primary lung cancer to the female reproductive tract has been documented, but clinicians should also be aware that metastasis to benign gynaecological tumours such as fibroids can also occur, especially in the setting of tumour-to-tumour metastasis. In addition, the clinical history and use of immunohistochemistry are invaluable in reaching a diagnosis.

Core tip: Our paper describes a rare occurrence of metastasis from a lung cancer to a uterine leiomyoma only without involvement of the endometrium, serosa or adnexae. This has not been reported in recent literature. We also describe the utility of immunohistochemistry in reaching a diagnosis which was essential in our patient who was asymptomatic-unlike those previously reported. The phenomenon of “tumour-to-tumour” metastasis, which not many gynaecologists have heard of, is also described in our report. The importance of knowing that the formation of metastasis to the female genital tract, although uncommon, is highlighted.

- Citation: Rauff S, Ng JS, Ilancheran A. Metastasis to a uterine leiomyoma originating from lung cancer: A case report. World J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 3(1): 21-25

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v3/i1/21.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v3.i1.21

Lung cancer metastasizes most frequently to the regional lymph nodes, the surrounding pulmonary structures, the liver, adrenal glands, bones and brain. Metastasis of this common malignancy to the female genital tract is unusual and specifically to the uterus, is rare. A review of the literature shows that the commonest site in the female genital tract to be affected by pulmonary metastasis is the ovary, with several cases documented so far[1-4]. Lung metastasis to the uterus is much rarer. To our knowledge, there have been only two cases of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with metastasis to the uterus reported in recent years - one to the uterine serosa and the other to the endometrium[5,6].

Here we report a rare case of an asymptomatic postmenopausal woman with lung cancer metastasis to a uterine leiomyoma.

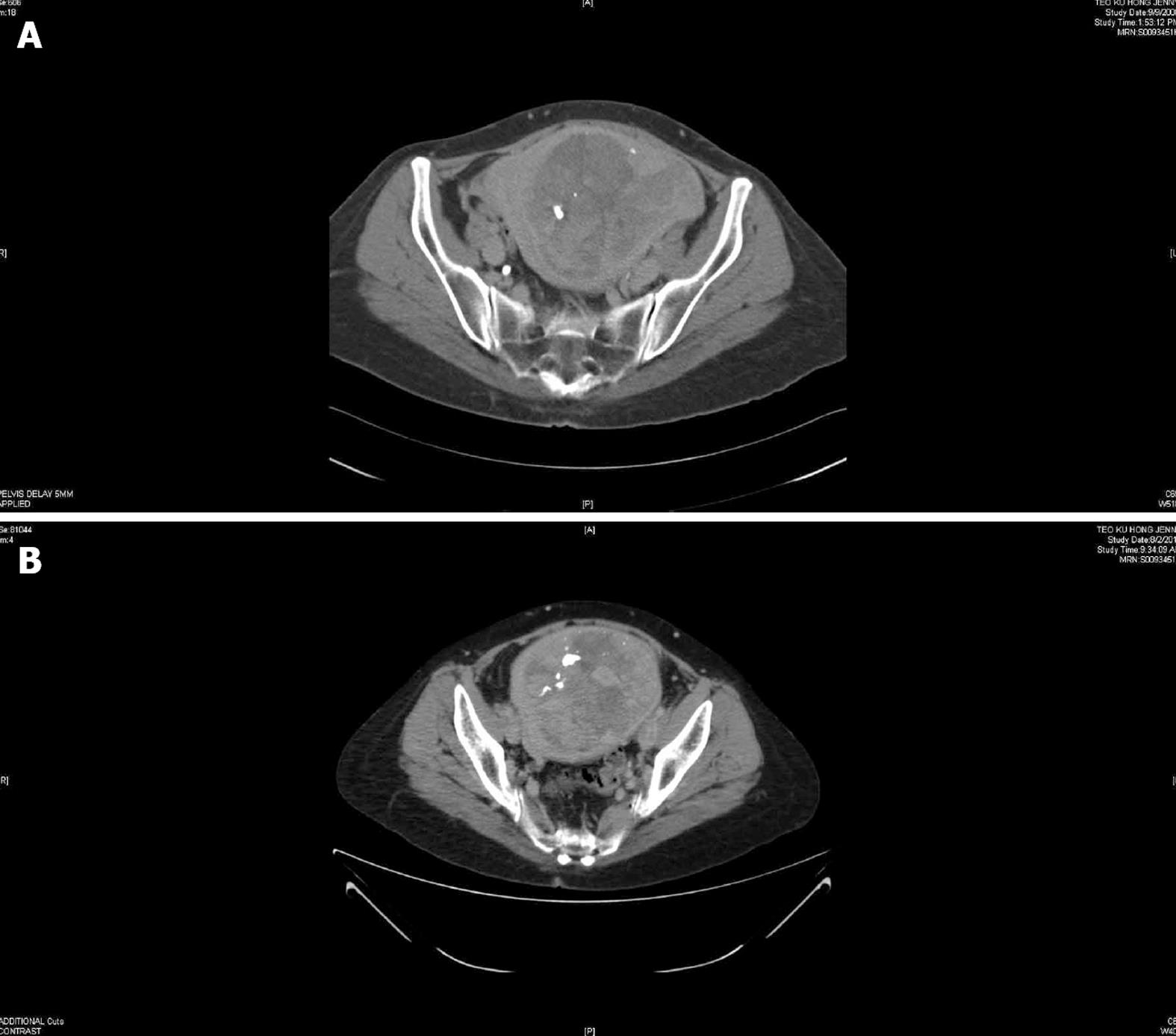

In July 2008, a 54-year-old postmenopausal Chinese woman, para 3, was diagnosed to have a non-small cell lung cancer. She had presented only with a cough of a six weeks’ duration and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed a 22 mm × 20 mm upper lobe left lung lesion. An incidental 150 mm × 150 mm uterine fibroid was also noted (Figure 1A). After a left upper lobectomy and lymphadenectomy her recovery was uneventful. Histology confirmed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with 2 out of 3 left hilar lymph nodes involved. The resection margins were free on tumour and the inferior pulmonary ligament lymph nodes were not involved. The tumour cells were positive for thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1). She was staged as IIA NSCLC (T1N1M0). She received adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and vinorelbine and remained disease free at subsequent follow-ups. The patient was a non-smoker whose only medical history was that of uterine fibroids which she had had since her first pregnancy, 23 years earlier. For her subsequent visits, a metastatic surveillance for the primary lung cancer was carried out with yearly CT scans of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. No further imaging, e.g., ultrasonography was performed for the uterine fibroid.

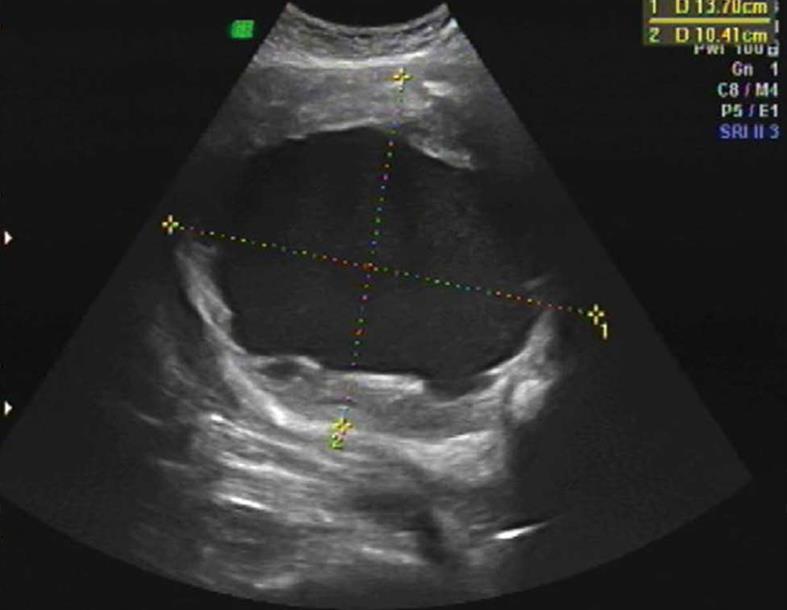

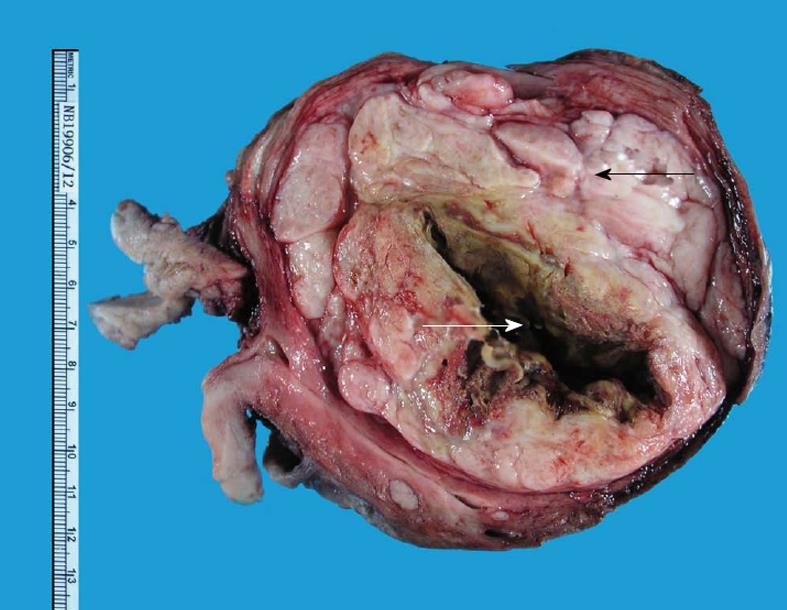

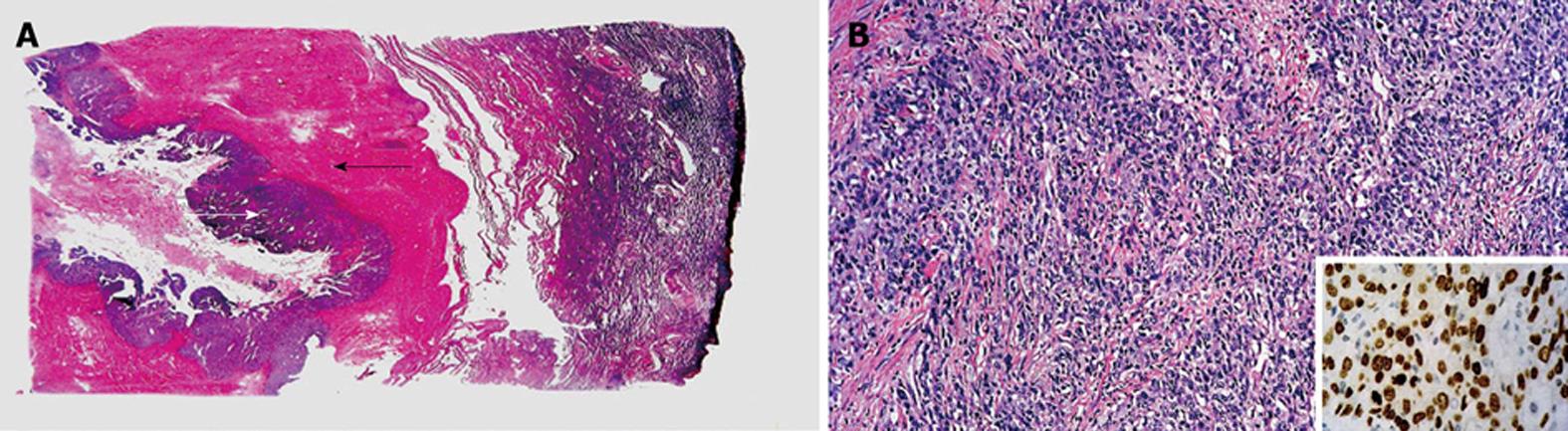

In September 2012, the patient was referred to our Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The uterine fibroid had increased slightly in size (170 mm × 160 mm) causing bilateral hydronephrosis noted on the annual CT scan done for metastatic surveillance (Figure 1B). There was no evidence of disease recurrence and the patient remained completely asymptomatic. Clinically, she had a firm, regular, mobile 22-cm uterine mass palpable. Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography revealed a cystic degenerative uterine mass (137 mm × 123 mm × 104 mm) with no increased vascularity demonstrated on Doppler studies suggesting a uterine leiomyoma (Figure 2). The ovaries were not visualised and endometrium was thin. Pap smear and renal function were normal. She underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in October 2012. Intra-operatively, a 24-wk size uterus was found with atrophic tubes and ovaries, all of which were removed intact to avoid any disease dissemination. The specimen was then cut open intra-operatively to confirm the impression was that of a degenerated fibroid with a cystic cavity filled with brownish fluid and some calcifications (Figure 3). The patient recovered uneventfully. The final histology report showed a poorly differentiated carcinoma consistent with metastatic lung cancer showing similar morphology to the previous pulmonary malignancy. Immunohistochemical staining was strongly positive for TTF-1 and cytokeratin (CK) 7. The lesion was confined to the leiomyoma with no involvement of the endometrium, cervix or adnexae (Figure 4). The resection margins were free of tumour.

Subsequent metastatic survey with CT and bone scans was performed and did not show any disease. At her last follow-up in May 2013, she remained in remission with no evidence of recurrence and was clinically well.

The most common extragenital primary sites resulting in metastases to the uterine corpus are the breast (42.9%), colon (17.5%), stomach (11.1%) and pancreas (11.1%). The lung accounts for less than 5% of extragenital primary tumours and most of these are adenocarcinomas, the most frequent subtype of NSCLC[7].

In recent literature, there have been two reported cases of NSCLC with metastasis to the uterus. The first case involved a patient who presented with postmenopausal bleeding and a uterine lesion on surveillance positron emission tomography/CT imaging. She had had previous lung resection for NSCLC 3 years earlier. Sixteen months post-operatively, she developed suspicious mediastinal lymphadenopathy. An endometrial sampling showed uterine carcinosarcoma and subsequent hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy revealed that besides the carcinosarcoma, there were other neoplastic foci in the uterine serosa, adenexae and cervix consistent with metastatic lung cancer[5]. The second case described a patient with advanced stage NSCLC treated with primary chemotherapy. Ten months after completing treatment, she complained of vaginal bleeding and ultrasonography showed an endometrial thickness of 10 mm. An endometrial biopsy confirmed endometrial metastasis from the primary lung cancer. A hysterectomy was not performed for this patient due to her clinical condition and advanced disease[6]. In both these cases, the patients had clinical symptoms (abnormal vaginal bleeding) and radiological abnormalities suggestive of a uterine malignancy. Differently from these reports, our patient was completely asymptomatic, had no evidence of disease progression or recurrence for 4 years since her initial diagnosis of lung cancer, had a long history of fibroids and there was no radiological suspicion of metastatic disease. She had not experienced any abnormal vaginal bleeding and the endometrium was thin thus an outpatient endometrial sampling was not performed unlike the previous cases. As the overall pre- and intra-operative impressions were that of a leiomyoma only, we performed an extrafascial hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy without surgical staging. The clinical picture here was neither consistent with a primary uterine malignancy nor with metastasis of a lung malignancy.

Although pathological examination did reveal leiomyoma, the final diagnosis was clinched by immunohistochemistry which is valuable in proving the primary origin of the malignant component. TTF-1 is a protein which stains positively in pulmonary adenocarcinomas and is sensitive and specific for respiratory and thyroid malignancies[8]. In this patient, her initial histology showed a lung cancer which stained for TTF-1 and the subsequent pathology report of the hysterectomy specimen also showed tumour cells similarly positive for TTF-1, ascertaining the pulmonary origin of the lesions in the leiomyoma. CK staining with CK7 and CK20 is also useful in distinguishing primary and metastatic lung adenocarcinomas from other malignancies, e.g., colorectal tumours. Primary and metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinomas show a typical CK7+/CK20- staining pattern which was comparable in our case, corroborating the diagnosis of lung cancer with metastasis and excluding a primary uterine malignancy[9].

Other metastatic sites in the female genital tract originating from the lung that have been reported include the cervix and vagina and these are rare too. In their analysis of 325 cases with metastasis to the female genital tract, Mazur et al[1] found that in 149 cases, the origin of the primary tumour was extragenital, the remainder being intragenital metastases. The ovaries and vagina were the most frequent sites of metastasis and most of these extragenital primaries were adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.

Tumour-to-tumour metastasis was described by Campbell et al[10] by the following strict criteria: there must be > 1 primary tumour, the recipient tumour being either benign or malignant (a leiomyoma in our case); the donor tumour must be a proven malignancy (lung adenocarcinoma in our case) and this must metastasize with an established growth in the recipient tumour. Finally, a pre-existing lymphoma must be excluded should metastatic lymphadenopathy occur. Our patient fulfils all the criteria for this uncommon phenomenon and to date, about 60 cases of metastasis from a malignancy to a benign tumour have been reported[11].

In conclusion, metastasis from a lung adenocarcinoma to the female genital tract is uncommon and to a uterine leiomyoma only is rare. Even in an asymptomatic patient with a long-standing history of a benign condition like fibroids and with no clinical evidence of disease recurrence for a few years, one should be aware that the formation of metastases can occur. The history of the initial disease and the use of immunohistochemical markers like TTF-1 and CK7 are essential in distinguishing between a primary versus metastatic uterine adenocarcinoma and localizing the pulmonary origin. Although there are not enough data to quote a prognosis for this patient, it would seem optimistic at this point as the metastatic survey post-operatively was negative and the metastatic tumour was completely resected with clear margins.

The clinical findings were that of a firm, regular, 22-cm uterine mass on abdominal and pelvic examination with a normal cervix and no adnexal masses.

The possible differential diagnoses of the pelvi-abdominal mass were a uterine fibroid, which was the most likely given the long-standing history and lack of symptoms, a uterine sarcoma or an ovarian pathology, which were less likely in view of the history, lack of symptoms and clinical findings.

Laboratory testing did not contribute greatly in this case and the main methods were a full blood count, renal function test and Pap smear cytology which were all normal.

A computed tomography scan of the thorax and abdomen was done which showed no recurrent lung disease but slight enlargement of the uterine fibroid causing upper urinary tract dilatation - this was confirmed on ultrasonography which was suggestive of degenerating uterine leiomyoma.

The gross pathological finding was that of a degenerated fibroid with a cystic cavity and the microscopic findings were that of metastasis of the original lung cancer to the uterine leiomyoma which was confirmed with immunohistochemical staining for thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and cytokeratin (CK) 7.

The treatment for the primary lung cancer was left upper lobectomy and lymphadenectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy and for the metastatic disease to the uterus, the treatment was total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Other contents would include the pattern of metastasis of primary lung cancer, i.e., mainly to the regional lymph nodes and liver/brain and the possibility of haematogenous spread to more distant organs like the uterus in this case.

TTF-1 is a protein nuclear transcription factor that is expressed in lung and thyroid tissue and is used in anatomic pathology as a marker to determine if a tumour arises from the lung or thyroid. CK7 is a protein found in the glandular epithelium of thyroid and breast tissue but not in others like the colon or prostate. It is commonly used in conjunction with CK20 to distinguish between colon cancer and other types e.g. ovarian.

Large uterine masses in the presence of a known primary malignancy may be associated with secondary (metastatic) disease rather than the commonly assumed primary uterine pathology.

The article reminds us that when clinicians encounter pelvic masses, it is important to think beyond the commoner gynaecological pathologies, especially in the setting of a known primary malignancy. The authors also aim to increase awareness of the phenomenon of “tumour-to-tumour” metastases and the value of immunohistochemistry in reaching a diagnosis to educate readers on these less commonly used but essential methods.

P- Reviewers: Celik H, Khajehei M, Nasu K, Tsikouras P, Zafrakas M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Mazur MT, Hsueh S, Gersell DJ. Metastases to the female genital tract. Analysis of 325 cases. Cancer. 1984;53:1978-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yeh KY, Chang JW, Hsueh S, Chang TC, Lin MC. Ovarian metastasis originating from bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a rare presentation of lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:404-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Young RH, Scully RE. Ovarian metastases from cancer of the lung: problems in interpretation--a report of seven cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1985;21:337-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Castadot P, Magné N, Berghmans T, Drowart A, Baeyens L, Smets D, Van Houtte P. Ovarian metastasis and lung adenocarcinoma: a case report. Cancer Radiother. 2005;9:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Parini CL, Mathis D, Leath CA. Occult metastatic lung carcinoma presenting as locally advanced uterine carcinosarcoma on positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:731-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tiseo M, Bersanelli M, Corradi D, Bartolotti M, Gelsomino F, Nizzoli R, Barili MP, Ardizzoni A. Endometrial metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma: a case report. Tumori. 2011;97:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kumar NB, Hart WR. Metastases to the uterine corpus from extragenital cancers. A clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Cancer. 1982;50:2163-2169. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Stenhouse G, Fyfe N, King G, Chapman A, Kerr KM. Thyroid transcription factor 1 in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:383-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kummar S, Fogarasi M, Canova A, Mota A, Ciesielski T. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 staining for the diagnosis of lung and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1884-1887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Campbell LV, Gilbert E, Chamberlain CR, Watne AL. Metastases of cancer to cancer. Cancer. 1968;22:635-643. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Pelissier-Komorek A, El Alami-Thomas W, Lebrun D, Diebold MD. Metastasis of endometrial adenocarcinoma in a primary lung adenocarcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2012;461:717-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |