Published online Nov 10, 2013. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v2.i4.185

Revised: July 3, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: November 10, 2013

Processing time: 201 Days and 22.8 Hours

AIM: To analyze safety and efficacy of pelvic arterial embolization (PAE) in preventing and treating obstetrical hemorrhage.

METHODS: A consecutive study of eight cases undergoing pelvic artery embolization from January 2010 to October 2012 in Department of Obstetric and Gynecology of Maulana Azad Medical College for intractable obstetric hemorrhage was done. All embolization were carried out in cath lab of cardiology Department at associated GB Pant Hospital.

RESULTS: Clinical success was defined as arrest of bleeding after PAE without need for repeat PAE or additional surgery which was 75% in our series. PAE was successful in controlling obstetrical hemorrhage in all except one who had mortality. Other had hysterectomy due to secondary hemorrhage. Five resumed menstruation. None of the women intended to conceive, hence are practicing contraception.

CONCLUSION: PAE is minimally invasive procedure which should be offered early for hemostasis in intractable obstetrical haemorrhage unresponsive to uterotonic. It is a fertility sparing option with minor complications.

Core tip: Historically obstetric hysterectomy was definitive treatment in morbid adherent placenta, cervical ectopic pregnancy and post partum hemorrhage refractory to medical and conservative surgical measures. Emergence of Pelvic arterial embolization as a minimally invasive procedure had led to alternative use of use of embolizing agents in controlling significant hemorrhage in various etiologies of obstetric hemorrhage thereby conserving fertility and reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. We used P- particle and coil as embolizing material with 75% success in our series. Our study further strengthens our confidence in pelvic artery embolization for its applicability in managing obstetric hemorrhage.

- Citation: Chaudhary V, Sachdeva P, Arora R, Kumar D, Karanth P. Pelvic arterial embolization in obstetric hemorrhage. World J Obstet Gynecol 2013; 2(4): 185-191

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v2/i4/185.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v2.i4.185

Pelvic arterial embolization (PAE) mainly uterine (UAE) or internal iliac artery is minimally invasive angiographic procedure which is used prophylactically and therapeutically in controlling obstetric hemorrhage (OH). Major causes of obstetrical hemorrhage include post partum hemorrhage (PPH), abnormal placentation, abruptio placenta, ectopic pregnancy and incomplete abortion[1,2]. PPH has been managed by uterine massage, uterotonics and packing. In refractory cases uterine suturing, stepwise vascular ligation and finally hysterectomy has been employed[3]. Placenta accreta and cervical pregnancy have been dealt by hysterectomy in past which causes loss of reproductive potential. PAE has emerged as a safe and effective alternative to surgery in controlling obstetric hemorrhage[4]. Ever since its first use by Brown et al[5], many have reported high success rates of PAE in obstetrical hemorrhage[6-8]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of PAE in treatment of obstetric hemorrhage and analyze its outcomes.

A consecutive study of eight cases undergoing embolization from January 2010 to October 2012 in Department of Obstetric and Gynecology of Maulana Azad Medical College for obstetric hemorrhage was done. Study was approved by our institutional review board. Causes of hemorrhage, comorbidities, preembolization treatments, technique, outcome and complications of embolization were analyzed. All embolization were done in cath lab of cardiology Department at associated GB Pant Hospital.

Eight cases underwent embolization for obstetrical emergencies (Table 1). Initial assessment and resuscitation were carried at our obstetric unit. Hemodynamic status, comorbidities, and presence or absence of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) were assessed. The shock was managed by administration of crystalloid or colloid and transfusion of specific blood units. Obstetric assessment included inspection of the vagina, cervix, and perineum for lacerations, hematomas and exploration of the uterine cavity for retained products. A multispecialty team including obstetric consultant, intensive care anesthetist and cardiologist decided the need for embolization after informed consent. The criteria for selection were active hemorrhage, deterioration of hemodynamic or clotting status despite treatment and high risk cases with anticipated hemorrhage. Angiography under C-arm was performed. Bilateral femoral approach using 5-French femoral arterial introducer was used. The internal iliac artery and uterine artery were catheterized via two puncture sites (one on each side). Angiography was performed to detect the site of bleeding from pelvic arteries. Highly selective angiography of uterine artery was attempted in four patients. Others had embolization of internal iliac artery (anterior branch) due to presence of severe uterine artery spasm not relieved by vasodilators. Coil embolization was done in all. Three had additional Polyvinyl Alcohol particle instillation. All except three patients were transferred to intensive care unit (ICU) or high dependency obstetric units for management after procedure.

| Cases | Indication | Age (yr) | Parity | Period of gestation | Previous sections |

| Case 1 | Cervical ectopic | 30 | G6P3A2L2, 11 wk | 12 wk | 2 |

| Case 2 | Placenta percreta | 28 | G3P2L1 | 36 wk | 1 |

| Case 3 | Placenta percreta | 38 | P3L3 | 28 wk | 3 |

| Case 4 | Placenta accreta | 30 | G3P1L1A1 | 27 wk | 1 |

| Case 5 | Placenta accreta | 30 | G3P1L1A1 | 36 wk + 5 d | 1 |

| Case 6 | PPH (Atonic + traumatic) | 30 | G2P1L1 | 36 wk | - |

| Case 7 | PPH (Atonic + traumatic) | 30 | PRIMI | 36 wk | - |

| Case 8 | PPH (Atonic + traumatic) | 28 | G3P2L1 | 40 wk | - |

Mean age was 30.5 years. Five patients had history of previous caesarean and abortions (Table 1). In five cases emergent embolization was done as all had massive hemorrhage following surgery or delivery despite conservative measures and developed coagulopathy (Table 2). Three had Prophylactic embolization for cervical ectopic and after classical section for placenta accreta percreta (n = 2). Conservative measures were uterotonic, cervical and vaginal tear repair in delivered cases and classical section with leaving placenta in situ for placenta accreta.

| Cases | Shock | Comorbidity | Blood loss (mL) | Coagulopathy | Mode of Delivery |

| Case 1 | - | - | 1300 | - | NA |

| Case 2 | - | Anaemia | 300 | - | Classical cs |

| Case 3 | + | Anaemia | 1000 | + | Classical cs |

| Case 4 | + | Anaemia | 1500 | + | Classical cs |

| Case 5 | - | Anaemia | 500 | - | Classical cs |

| Case 6 | + | Anaemia, precipitate labor | 1000 | + | NVD |

| Case 7 | + | Jaundice, anaemia | 1500 | + | NVD |

| Case 8 | + | - | 2500 | + | Forceps |

All but one had primary hemorrhage. Secondary hemorrhage occurred on day forty post classical preterm section done for placenta percreta. Six patients were moderately anaemic. Five patients were build up to adequate levels by packed cell transfusion prior to labor or section. Other presented in shock due to secondary hemorrhage and had correction after emergent embolization. All adherent placentas were previa as diagnosed by Doppler ultrasound and supplemented by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in two cases. All underwent conservative surgical management with embolization. One had secondary hemorrhage post classical section which responded to primary embolization. Placenta resorbed in all.

Three cases underwent embolization for Atonic and traumatic PPH due to cervical tears unresponsive to uterotonic and repair (Table 3). Emergent CT revealed unilateral broad ligament hematoma in two. Both had massive blood loss following delivery. Traumatic PPH was initially controlled in first. Constant trickling reappeared after twenty hours, so underwent embolization while on ventilatory support. Bleeding stopped and hematoma resolved spontaneously. Second case underwent immediate embolization due to persistent bleeding despite repair, with success. Third case had massive PPH following forceps delivery and had cardiac arrest forty minutes later because of hemorrhagic shock and was on ventilatory support. Clinically pelvic hematoma was suspected as evident by uterine deviation and abdominal fullness. Poor general condition prevented immediate imaging and surgical intervention. Patient was shifted to ICU where bleeding continued and hematocrit continued to fall in spite of blood transfusion. Emergency CECT pelvis revealed left supra-levator pelvic hematoma of size 12 cm × 10 cm. Patient underwent embolization but had cardiac arrest and expired shortly. Arrest was not related to embolization. Five patients were in coagulopathy which was corrected in two prior to embolization. Three underwent emergent PAE in coagulopathy unresponsive to conservative measures and had ongoing correction during and after embolization with success.

| Cases | Type of embolization | Type | Additional treatment | Time from presentation to start of embolization | Embolic agent |

| Case 1 | Uterine | Prophylactic | Methotrexate | 4 h | Coil + PVA particle |

| Case 2 | Uterine | Prophylactic | Methotrexate + uterotonic | 3 h | Coil |

| Case 3 | Uterine | Emergency | Methotrexate + uterotonic | 1 h | Coil+PVA |

| Case 4 | Internal iliac artery | Emergency | Methotrexate + uterotonic | 1 h | Coil |

| Case 5 | Uterine artery | Prophylactic | Methotrexate + uterotonic | 30 min | Coil + PVA |

| Case 6 | Internal iliac artery | Emergency | Uterotonic + cervical tear repair | 2 h | Coil |

| Case 7 | Internal iliac artery | Emergency | Uterotonic + cervical tear repair | 22 h | Coil |

| Case 8 | Internal iliac artery | Emergency | Uterotonic + cervical tear repair | 26 h | Coil |

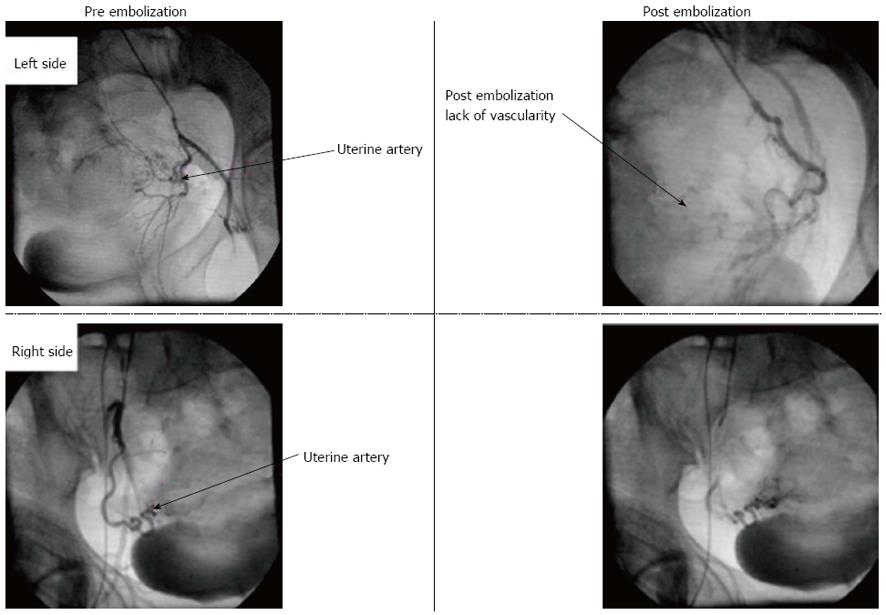

Post embolization angiogram revealed arrest of bleeding in all patients (Figure 1). Transfusion was required in all patients. No major complications during or post embolization was noted. Minor complications were fever (n = 2), mild groin pain (n = 2) and correctable sepsis (Table 4). Initially, PAE was successful in controlling hemorrhage and partial resolution of cervical ectopic as evident by falling beta- HCG levels. Patient presented with secondary intractable hemorrhage on day twenty one and hysterectomy was undertaken as there was technical difficulty in shifting to cath lab.

| Cases | Hemorrhage controlled | Rebleeding after embolization | hysterectomy | Transfusion of blood and its products | Post embolization fever | Sepsis | Groin pain | Resumption of menstrual cycles | Mortality |

| Case 1 | + | + | + | + | - | - | _ | - | - |

| Case 2 | + | - | - | + | + (Non embolization) | + (UTI) | + | + | - |

| Case 3 | + | Mild, Hemostatics uterotonics | - | + | + | - | _ | + | - |

| Case 4 | + | + Mild, Hemostaticsuterotonics | - | + | - | - | _ | - | - |

| Case 5 | + | Mild, Hemostaticsuterotonic | - | + | - | - | _ | + | - |

| Case 6 | + | - | - | + | +Non embolization cause | + UTI, Puerperal Sepsis post exploration | + | + | - |

| Case 7 | + | - | - | + | + | - | _ | + | - |

| Case 8 | Expired after embolization | Not applicable | + |

Clinical success was defined as cessation of bleeding after PAE without need for repeat PAE or additional surgery. PAE was successful in controlling obstetrical hemorrhage in all except one who had mortality as this patient was severely hemodynamically compromised. One required hysterectomy due to secondary hemorrhage. Clinical success in our series was 75%. In six cases mean time was three hours and twenty four hours in two. Five resumed menstruation and two are at present lost to follow up. None of the women intended to conceive, hence are practicing contraception.

Obstetrical hemorrhage is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide. PPH is major contributor[1]. Primary PPH is defined as excessive bleeding from genital tract of 500 mL or more in first 24 h following delivery[4]. Management is centered on administration of uterotonic, uterine packing and conservative surgical vessel ligations. Internal-iliac-artery ligation may not be effective in controlling severe PPH in half of patients as blood flow in the distal vessel is decreased to 48% due to rich collateral network. Uterine artery ligation has 80% success in uterine atony, but is less effective in placenta accreta. Last resort is hysterectomy which causes significant morbidity and loss of reproductive potential. With advances in interventional radiology, PAE has emerged as an accepted option in refractory PPH[9]. Its advantage lies in its high success rates relative to ligation and hysterectomy[10].

Embolization was first used in 1972 to control arterial bleeding in pelvic fractures. First successful use of femoral transcatheter pelvic arterial embolization in PPH was described by Brown in 1979[5]. The reported success rate of UAE is over 90% to 100% in PPH due to atony[6,11]. Arterial embolization is performed at a more distal and specific location than vessel ligation which prevents bleeding through collaterals. Pelage et al[6] evaluated the efficacy and safety of selective arterial embolization in thirty-five women with intractable PPH. Hemostatic embolization of uterine arteries was performed in all including two cases which underwent hysterectomy. Bleeding stopped immediately. Two patients required repeat embolization. Delayed hysterectomy was undertaken in case of placenta accreta[6]. Lee et al[8] published largest retrospective single-center study in women who underwent PAE for primary PPH in terms of efficacy and factors associated with failure of embolization procedure. Thirty-two patients had a clinical diagnosis of DIC. Overall bleeding control was achieved in 98.0% of the patients. Clinical success was 86.5%. Bleeding vessels, commonly bilateral uterine arteries as seen on angiography were embolized.

Embolization has a significant success in Secondary PPH. It is defined as excessive bleeding from the genital tract, with a blood loss of 500 mL or more, occurring after the first 24 h following delivery until the 6th-12th week of the puerperium. It affects 1%-3% of all deliveries[7]. Secondary PPH is managed with uterotonics and curettage. If bleeding persists vascular ligation or hysterectomy is required. Hence, transcatheter embolization of the uterine or pelvic arteries is an alternative in controlling secondary hemorrhage. Its first successful use was described by Pelage et al[7] in fourteen women unresponsive to uterotonic drugs or uterine curettage. We in one case of secondary hemorrhage in conservatively managed placenta percreta used UAE with success.

Angiographic embolization is effective in managing obstetric hemorrhage due to pelvic hematomas. It is difficult to identify bleeding vessel during exploration of hematoma due to friable genital tissues. Obstetrician must repair cervical and vaginal tears and correct coagulopathy prior to embolization to achieve therapeutic success[2,8]. But with ongoing hemorrhage and coagulopathy, emergent embolization can be used as it stems hemorrhage and causes hematoma resolution, facilitates uterine contractions releasing procoagulant factors into circulation[8]. Deux reported rapid improvement in clotting disorders and hemodynamic status after PAE[2]. Therapeutic success was 96%. Vascular spasms were dealt with injecting vasodilator thereby allowing selective catheterization[6,12].

Abnormal placentation is one of the etiological factors in intractable PPH. Placenta accreta is characterized by villi abnormally adherent to the myometrium due to the absence or defects in the normal decidual basalis and fibrinous Nitabuch layer[13,14]. Recently, rate of placenta accreta has increased in conjunction with the rate of cesarean deliveries at a frequency of 1 per 2500[15]. Placenta accreta has become leading cause of failed vessel ligation and peripartum hysterectomy[13,15]. Presence of placenta previa and prior cesarean delivery exponentially increases the risk. Antenatal diagnosis by doppler ultrasound or MRI allows either scheduled conservative management or hysterectomy thereby decreasing morbidity[15]. Management recommended is a cesarean-hysterectomy with placenta in situ in multiparous women not willing to conceive[16,17]. However hysterectomy is associated with significant morbidity like bladder and ureteric injury and renders woman sterile. Recent literature shows that leaving adherent placenta in utero followed by embolization avoids hysterectomy, maintains fertility with successful pregnancies in women desirous to conceive[18]. Leaving placenta in situ may result in infection and secondary PPH, which are dealt with appropriate antibiotics and repeat embolization. In a large multicenter study by Sentilhes et al[13] conservative methods were successful in avoiding hysterectomy in 78.4% of women, with a severe maternal morbidity rate of only 6%. In subsequent follow up of women contacted, 92% resumed menstruation. Eighty-eight point nine percent of women achieved successful pregnancy among who wished to conceive. Placenta accreta recurred in 28% of cases. They concluded conservative treatment for placenta accreta doesn’t compromise patients’ subsequent fertility or obstetric outcome[17]. Prophylactic insertion of balloon catheters before cesarean section is effective method in controlling anticipated bleeding[19]. Embolization can be carried out without delay after uterine closure. We in two cases of adherent placenta carried prophylactic embolization immediately after classical section. It had less blood loss, surgery time and minimal complication. Methotrexate has been proposed as adjuvant treatment to hasten the postpartum involution of the uterus. No evidence currently supports its efficacy in conservative management of accreta. All our cases of adherent placenta received methotrexate with no complications. We believe conservative approach has less morbidity and preserves reproductive function and should remain first line management in adherent placenta.

Embolization is an emerging modality in conservative management of cervical ectopic. On reviewing literature PAE with methotrexate is effective in reducing the ectopic cervical mass. There is always a risk of haemorrhage which can be dealt with repeat PAE. Hysterectomy should be last resort if all conservative methods fail[20].

Clinical success of PAE for treatment of severe PPH lies in rapid transfer and timely decision for embolization. The time from decision for embolization to achievement of hemostasis should be in the order of 2-6 h[21].

Several prognostic factors are associated with clinical success of embolization. Shock, DIC, Massive blood transfusion, genital tears, caesarean delivery, and placenta accreta are poor prognostic factors in embolization in different case series[6,8,22]. Lee et al[8] showed that DIC and massive transfusion of more than ten red blood cell units were significantly related to clinical failure.

Abnormal placentation accounts for over half of the failures of UAE[6]. Failure is thought to be due to myometrial injury caused by difficult digital separation of the placenta. Massen performed juxta renal angiogram in UAE failures and occluded ovarian arteries in PPH[23]. PAE after a failed surgical procedure is not associated with unfavorable clinical outcome[24]. In our series embolization was successful in patients with hemodynamic shock, coagulopathy, abnormal placentation and prevented morbidity. PAE should be considered in hemodynamically unstable patients and in patients with coagulopathies but these patients require close monitoring in an ICU set up.

Embolization is associated with complications. Minor complications are pain, transient fever, mild transient numbness of the buttock, foot or thigh, hematoma formation at the site of common femoral artery puncture, and pelvic infection[11,25]. Lee et al[8] reported asymptomatic dissection of the uterine artery and edema of the lower legs after PAE with no major complications. Complications from embolus migration to general blood circulation are very rare. Early intervention in form of confirmation of embolus by angiogram, anticoagulation and embolectomy can prevent loss of limb or its function[23]. Serious complications like uterine and bladder necrosis, delayed vesicovaginal fistula after PAE are reported[23,25]. Proper informed consent from patient must be taken before embolization.

The effects of PAE on menstruation and fertility are unclear. Successful pregnancies and resumption of menstruation have been reported unanimously in many case series studying long term effects of PAE[12,17,26-28]. Lee et al[8] reported resumption of regular menstruation in 97.3% of women after PAE. Sentilhes et al[12] analyzed sixty eight women who underwent embolization for PPH. 92% resumed menstruation. Those who desired pregnancy were able to conceive. Delotte in his review article included thirteen articles. Fertility follow-up of a total of one sixty eight women after PAE were analyzed. Clinical success of embolization was in 92%. Total forty five pregnancies were described of which thirty two cases resulted in live births[28]. Embolization doesn’t seem to affect fertility and menstruation.

In conclusion, we present two failures and six successes in various etiologies of obstetric hemorrhage in our series. Correction of shock and DIC increases success but embolization should not be delayed while attempting to correct above. Embolization should be done in rebleeding. Non selective embolization of anterior branch of internal iliac artery can be attempted if there is technical difficulty in accessing uterine artery in vascular spasm. It has similar efficacy and has minimal complications. We believe planned embolization in case of morbid adherent placenta irrespective of parity leads to less morbidity and early recovery. Caesarean hysterectomy should be an alternative choice if embolization fails in morbid adherent placenta. Use of embolization as last resort is to be discouraged and should be early means of hemostasis in obstetric hemorrhage unresponsive to uterotonic.

Pelvic arterial embolization is minimally invasive procedure in modern obstetrics, which is a safe alternative to surgical methods in conditions causing intractable obstetrical hemorrhage and is a fertility sparing option with minor complications.

Uterine artery embolization in obstetrics was first described by Pelage et al in primary postpartum hemorrhage. Subsequently its use in obstetrics have been extended to embolization of pelvic arteries in management of primary and secondary post partum hemorrhage ,traumatic hemorrhage, placenta accreta and cervical ectopics thereby conserving fertility and reducing morbidity.

Pelvic arterial embolization immediately stems hemorrhage arising from pelvic arteries and has emerged an effective hemostatic option in developing countries at tertiary level hospital. Research area is directed towards long term effects of embolization for which randomized control data is needed.

Authors’ paper highlights the clinical success in managing cases with obstetric hemorrhage using embolization which otherwise might have needed hysterectomy. Its advantage lies in its high success rates relative to ligation and hysterectomy in controlling hemorrhage.

Pelvic arterial embolization (PAE) can be applied as minimally invasive choice in post partum hemorrhage refractory to medical measures, prior to classical section in placenta accreta and in live cervical ectopics. Hemodynamic instability should not be considered a contraindication for PAE.

Pelvic arterial Embolization- embolization of internal iliac, uterine artery and its branches using polyvinyl alcohol particles or coil.

This study was a case series to assess efficacy of PAE for varying etiologies of obstetric hemorrhage. It was a useful intervention option in hemorrhaging patients as it stemmed hemorrhage, reduced surgical morbidity, thereby conserving fertility in 75% of the patients.

P- Reviewers: TinelliA, Wang PH, Zhang XQ S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Al-Zirqi I, Vangen S, Forsen L, Stray-Pedersen B. Prevalence and risk factors of severe obstetric haemorrhage. BJOG. 2008;115:1265-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Deux JF, Bazot M, Le Blanche AF, Tassart M, Khalil A, Berkane N, Uzan S, Boudghène F. Is selective embolization of uterine arteries a safe alternative to hysterectomy in patients with postpartum hemorrhage? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:145-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. Geneva: World Health Organization 2004; . |

| 4. | Gonsalves M, Belli A. The role of interventional radiology in obstetric hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:887-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brown BJ, Heaston DK, Poulson AM, Gabert HA, Mineau DE, Miller FJ. Uncontrollable postpartum bleeding: a new approach to hemostasis through angiographic arterial embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;54:361-365. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pelage JP, Le Dref O, Mateo J, Soyer P, Jacob D, Kardache M, Dahan H, Repiquet D, Payen D, Truc JB. Life-threatening primary postpartum hemorrhage: treatment with emergency selective arterial embolization. Radiology. 1998;208:359-362. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pelage JP, Soyer P, Repiquet D, Herbreteau D, Le Dref O, Houdart E, Jacob D, Kardache M, Schurando P, Truc JB. Secondary postpartum hemorrhage: treatment with selective arterial embolization. Radiology. 1999;212:385-389. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lee HY, Shin JH, Kim J, Yoon HK, Ko GY, Won HS, Gwon DI, Kim JH, Cho KS, Sung KB. Primary postpartum hemorrhage: outcome of pelvic arterial embolization in 251 patients at a single institution. Radiology. 2012;264:903-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Arulkumaran S, Walker JJ, Watkinson AF, Nicholson T, Kessel D, Patel J. The role of emergency and elective interventional radiology in postpartum hemorrhage. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Good Practice Guideline, 2007-01-06, cited 2013-10-06. Available from: http: //www.rcog.org.uk/womenshealth/clinicaLguidance/roleemergency-and-electiveinterventional-radiology- postpartum-haem. |

| 10. | Pelage JP, Limot O. [Current indications for uterine artery embolization to treat postpartum hemorrhage]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2008;36:714-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Soncini E, Pelicelli A, Larini P, Marcato C, Monaco D, Grignaffini A. Uterine artery embolization in the treatment and prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;96:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sentilhes L, Gromez A, Clavier E, Resch B, Verspyck E, Marpeau L. Fertility and pregnancy following pelvic arterial embolisation for postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG. 2010;117:84-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sentilhes L, Ambroselli C, Kayem G, Provansal M, Fernandez H, Perrotin F, Winer N, Pierre F, Benachi A, Dreyfus M. Maternal outcome after conservative treatment of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:526-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hull AD, Resnik R. Placenta accreta and postpartum hemorrhage. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:228-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tikkanen M, Paavonen J, Loukovaara M, Stefanovic V. Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta leads to reduced blood loss. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:1140-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Placenta accreta. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 266. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002;77:77–78. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sentilhes L, Kayem G, Ambroselli C, Provansal M, Fernandez H, Perrotin F, Winer N, Pierre F, Benachi A, Dreyfus M. Fertility and pregnancy outcomes following conservative treatment for placenta accreta. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2803-2810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Provansal M, Courbiere B, Agostini A, D’Ercole C, Boubli L, Bretelle F. Fertility and obstetric outcome after conservative management of placenta accreta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:147-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ojala K, Perälä J, Kariniemi J, Ranta P, Raudaskoski T, Tekay A. Arterial embolization and prophylactic catheterization for the treatment for severe obstetric hemorrhage*. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:1075-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hirakawa M, Tajima T, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Ishigami K, Yahata H, Wake N, Honda H. Uterine artery embolization along with the administration of methotrexate for cervical ectopic pregnancy: technical and clinical outcomes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1601-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Boulleret C, Chahid T, Gallot D, Mofid R, Tran Hai D, Ravel A, Garcier JM, Lemery D, Boyer L. Hypogastric arterial selective and superselective embolization for severe postpartum hemorrhage: a retrospective review of 36 cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:344-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Poujade O, Zappa M, Letendre I, Ceccaldi PF, Vilgrain V, Luton D. Predictive factors for failure of pelvic arterial embolization for postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Maassen MS, Lambers MD, Tutein Nolthenius RP, van der Valk PH, Elgersma OE. Complications and failure of uterine artery embolisation for intractable postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG. 2009;116:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sentilhes L, Gromez A, Clavier E, Resch B, Verspyck E, Marpeau L. Predictors of failed pelvic arterial embolization for severe postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:992-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Porcu G, Roger V, Jacquier A, Mazouni C, Rojat-Habib MC, Girard G, Pellegrin V, Bartoli JM, Gamerre M. Uterus and bladder necrosis after uterine artery embolisation for postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG. 2005;112:122-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chauleur C, Fanget C, Tourne G, Levy R, Larchez C, Seffert P. Serious primary post-partum hemorrhage, arterial embolization and future fertility: a retrospective study of 46 cases. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1553-1559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gaia G, Chabrot P, Cassagnes L, Calcagno A, Gallot D, Botchorishvili R, Canis M, Mage G, Boyer L. Menses recovery and fertility after artery embolization for PPH: a single-center retrospective observational study. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:481-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Delotte J, Novellas S, Koh C, Bongain A, Chevallier P. Obstetrical prognosis and pregnancy outcome following pelvic arterial embolisation for post-partum hemorrhage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |