Published online Nov 10, 2013. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v2.i4.137

Revised: March 12, 2013

Accepted: April 13, 2013

Published online: November 10, 2013

Processing time: 339 Days and 6.2 Hours

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) represents approximately 90% of primary malignant ovarian tumors, the sixth most common cancer in women and the second most common gynecologic cancer. Approximately 80%-85% of all ovarian carcinomas in Western society are serous and up to 95% of patients are in advanced stages (FIGO stage III-IV) at diagnosis. Treatment of ovarian cancer is mainly based on three key approaches: surgical removal of neoplasia; chemotherapy to kill cancer cells; direct chemotherapy on peritoneal surfaces. The application of hyperthermic chemotherapy to the peritoneal cavity (HIPEC) after radical surgery may also be an attractive option. We analyzed the natural history of EOC in the literature and identified various time-points where sensitivity to chemotherapy, freedom from disease and overall survival are different. We propose eight time-points in EOC history with homogeneous oncological findings. The effectiveness of HIPEC in EOC treatment should be evaluated based on these eight time-points and we believe that retrospective and prospective studies of HIPEC should be evaluated according to these time-points.

Core tip: The standard treatment for advanced ovarian cancer consists in complete cytoreductive surgery and intravenous combination chemotherapy with a platinum compound and a taxane. Although response rates to initial therapy are high, many patients will recur and die of peritoneal carcinomatosis. The addition of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) to the standard therapy aims at increasing survival by reducing peritoneal recurrence. In this review we discuss the time points where HIPEC can be proposed.

- Citation: Iaco PD, Perrone AM, Procaccini M, Pellegrini A, Morice P. Natural history of epithelial ovarian cancer and its relation to surgical and medical treatment. World J Obstet Gynecol 2013; 2(4): 137-142

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v2/i4/137.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v2.i4.137

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) represents approximately 90% of primary malignant ovarian tumors, the sixth most common cancer in women and the second most common gynecologic cancer[1]. At diagnosis, the majority of patients (70%) are in advanced stage of the disease (FIGO IIB-IV) with rapid and asymptomatic widespread cancer cells in the pelvic structure and peritoneal cavity[2]. Disease stage at presentation is the most important prognostic factor determining outcome; 70%-80% of women at stage I survive for five years compared to only 15% of those at stage IV[3].

Recent advances in pathology and genetics have shown that EOC is a heterogeneous disease with various risk factors, genetic abnormalities and oncological pathways that partly determine biological behavior, response to chemotherapy, and prognosis[4]. A dualistic model places the major histological types into two groups: types I and II. Type I cancers (mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell carcinomas and low-grade serous carcinomas) demonstrate a relatively insidious clinical course with generally better prognosis. These develop in a stepwise fashion from well-established precursor lesions, such as borderline tumors and endometriosis[5,6]. Type I are relatively genetically stable and typically display a variety of somatic mutations in genes including K-ras, BRAF, PTEN, CTNNB1 but very rarely TP53. In contrast, Type II cancers (high-grade serous carcinomas, high-grade transitional carcinomas, malignant mixed mesodermal tumors and undifferentiated carcinomas) are extremely aggressive neoplasms with remarkable early sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy but are frequently diagnosed at advanced stages. They are chromosomally highly unstable and harbour TP53 mutations in more than 95% of cases[7,8]. Approximately 80%-85% of all ovarian carcinomas in Western society are serous. Up to 95% of patients with FIGO stage III-IV disease have serous carcinomas whereas FIGO stage I serous carcinomas are uncommon[9,10].

Like other cancers, EOC can spread through lymphatic and blood vessels to nodes and parenchyma of distant organs (liver, lung and brain). However, a distinctive feature of these tumors is their ability to spread from the ovary to the abdominal cavity, forming nodules of variable size on the surface of the parietal and visceral peritoneum, including the omentum. The coalescence of nodules forms plaque or masses in the abdominal-pelvic cavity. Blockage of diaphragmatic lymphatics prevents outflow of proteinaceous fluid from the peritoneal cavity, causing the accumulation of ascites in advanced disease. Tumor dissemination from the peritoneal cavity to the pleural cavity occurs through the diaphragmatic peritoneum and leads to pleural effusion[11,12].

The main treatment of advanced disease consists of surgical removal of all visible nodules in the abdominal cavity followed by intravenous chemotherapy (platinum-based drugs with or without taxanes). The combined effect of surgery and chemotherapy is often the complete eradication of cancer cells.

Treatment of ovarian cancer is mainly based on three key areas: surgical removal of neoplasia; chemotherapy to kill cancer cells; application of chemotherapy directly on peritoneal surfaces.

In advanced disease (FIGO stage IIB-IIIC) the surgical removal of neoplasia with optimal cytoreduction (nodules ≤ 1 cm left) is recommended. An additional survival advantage of complete cytoreduction (no visible residual disease) has been recently reported[12]. Several studies have shown that specialized gynecological oncologist surgeons are more likely to perform optimal surgery than general surgeons[13]. The frequent presence of multiple neoplastic implants on peritoneal surfaces together with pelvic and upper abdominal organs implies that surgeons must be prepared to remove organs beyond the pelvis, such as peritoneal surfaces of colic gutters, diaphragmatic domes, and to carry out surgical procedures on the colon, bowel, liver, gallbladder, stomach, and spleen. This implies multidisciplinary surgical effort and the possibility of higher postoperative morbidity. This idea has not been accepted by the majority of gynecologic oncologists due to the lack of scientific data. If initial maximal cytoreduction is not carried out, interval debulking surgery (IDS) should be considered in patients responding to chemotherapy or with stable disease. IDS should ideally be carried out after three cycles of chemotherapy then followed by three further chemotherapy cycles[14].

Chemotherapeutic efficacy for ovarian carcinoma showed a dramatic shift after the introduction of platinum compounds and since 1996 the combination of platinum plus paclitaxel has been the standard treatment. The current rationale of six cycles of treatment as standard is based on three randomized trials which analyzed the impact of chemotherapy duration (i.e., number of cycles) on OS. None of these studies demonstrated a difference in median survival time, but longer durations were associated with increased toxicity, especially neuropathy[15]. Other chemotherapy regimens, such as gemcitabine and liposomal doxorubicin in association with carboplatin-paclitaxels were compared to carboplatin-plaxitel alone in the Phase III Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) trials (GOG 0182-ICON 5). These showed no statistically significant superiority or clinically useful benefit associated with the three drugs compared to the controls. Currently carboplatin-paclitaxel remains the treatment of choice even though angiogenesis inhibitors in combination with the standard treatment have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration[16]. The main issue with EOC is the chemo sensitivity of cancer cells. Data shows that only 50% of patients have a complete clinical response to standard IV chemotherapy and that 30% of them have microscopic metastasis at surgical exploration. Most advanced stage patients who achieve clinical remission after completion of initial treatment develop recurrent disease and drug resistance, and their cure rate is less than 30%. These factors are major limitations in the treatment of patients with EOC. In order to overcome these limitations, different treatments such as secondary cytoreduction, second line chemotherapy drugs, high dose chemotherapy, intra-peritoneal (IP) chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and hormone therapy should be considered. To date, none of these approaches, apart from IP chemotherapy, has been found to have a significant impact on survival[17].

IP chemotherapy refers to the administration of cytotoxic agents directly to the peritoneal cavity. The rationale is that a higher concentration of cytotoxic drugs and longer duration of exposure can be achieved while reducing the toxicity normally associated with intravenous therapy[18-20]. In fact, IP administered cytotoxic drugs can directly target tumor masses confined to the abdominal cavity, thus bypassing the poor vascularization of small volume disease and thereby increasing peri- and intra-tumoral drug concentration. Cisplatin can penetrate small volume tumors to a maximum depth of 1-3 mm and may therefore only benefit those patients with microscopic residual disease. By using large intra-peritoneal doses, the tumor surface can be exposed to high concentrations of cisplatin with only a small amount of drug leaking into the circulation. By this means, the amount of cisplatin reaching the tumor through capillaries is doubled when compared to the maximum tolerated dose delivered intravenously. Several studies have documented the advantages of IP compared to IV chemotherapy[20]. Post-operative adhesions after cytoreductive surgery can limit the access of the active drug to tumor areas and other complications, such as infections due to the IP catheter, may occur. Intra-operative administration of IP chemotherapy has been designed to overcome such obstacles. Intra-peritoneal hyperthermia chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a new treatment method based on increasing the sensitivity of cancer cells to the direct cytotoxic effect of chemotherapeutic agents at high temperature and increasing the concentration of chemotherapeutic agents that penetrate cancer tissues[21-23].

Approximately 70% of patients with advanced cancer who experience clinical remission after initial surgery and chemotherapy will develop recurrent disease[24].

In general, patients who progress during treatment with platinum are considered to have “platinum-refractory” disease and patients who show recurrence < 6 mo after completion of first-line platinum chemotherapy are considered to have “platinum resistant” disease. These patients are candidates for salvage therapy with second line chemotherapy. Patients who relapse after an interval of > 6-12 mo are defined as “platinum-sensitive” and are candidates for chemotherapy and/or surgery. The concept of chemo-sensivity is based on clinical data; re-subjecting the patient to the previous chemotherapy regimen obtains about a 20% response, but drug administration is the only method by which to verify cell response. Because of the late onset of relapse, platinum-sensitive patients should in reality be regarded as including both chemo-sensitive and chemo-insensitive patients[25].

Appropriate treatment of recurrence (chemotherapy/surgery), which may be based on time and nature of relapse and the role of surgery, remains a field of discussion and controversy.

In general, surgical resection may be considered in platinum-sensitive patients. Resectable disease, good performance status and complete secondary cytoreduction are one of the best predictors of survival in these patients[26-28].

In ovarian platinum-sensitive recurrence, surgical cytoreduction offers the following potential benefits: (1) cytoreduction of tumor volume offers patients a greater chance of response to chemotherapy; and (2) the elimination of potentially chemo-resistant cells. However, surgical cytoreduction is generally not undertaken without also scheduling postoperative chemotherapy since surgery alone rarely offers a cure.

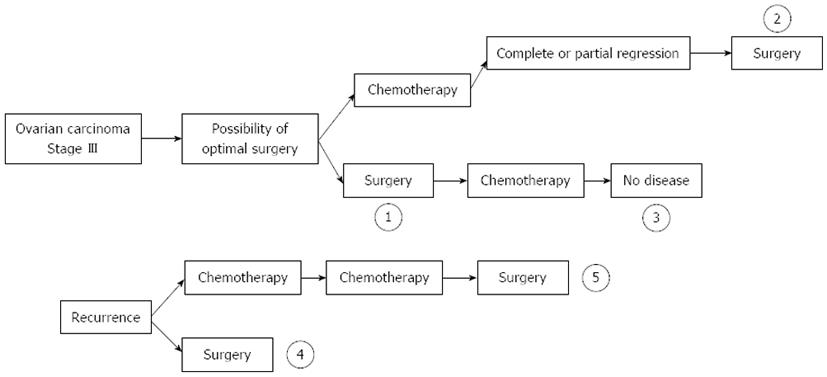

We analyzed literature using the search terms “ovarian cancer” and “HIPEC treatment”. EOC naturally presents various time-points where surgery, chemotherapy or HIPEC can be identified with homogenous chemo-sensitivity, response to therapy, and survival. Chua et al[27] proposed five time-points: (1) time of primary treatment; (2) time of IDS; (3) time of consolidation therapy after complete pathological response following initial therapy; (4) time of first recurrence; or (5) time of salvage therapy (Figure 1). The results of the most important paper are shown in Table 1[28-49].

| Ref. | Patients (n) | Time-point of optimal cytoreduction | Median disease free survival (mo) | Overall 3-yr survival (%) | Overall 5-yr survival (%) |

| Ansaloni et al[21] | 39 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | 421 | NR | NR |

| Deraco et al[28] | 56 | 4, 5 | NR | NR | 23 |

| Pomel et al[30] | 31 | 2, 3 | 27 | 672 | NR |

| Bereder et al[31] | 246 | 2, 4, 5 | 13 | 60 | 35 |

| Pavlov et al[32] | 56 | 1, 4, 5 | 26 | NR | NR |

| Fagotti et al[33] | 25 | 4, 5 | 10 | NR | NR |

| Guardiola et al[34] | 47 | 2 | 14 | 632 | NR |

| Di Giorgio et al[35] | 47 | 1, 4, 5 | 20 | NR | 17 |

| Bae et al[36] | 67 | 2, 3 | NR | NR | 66 |

| Cotte et al[37] | 81 | 5 | 19 | NR | NR |

| Helm et al[38] | 18 | 5 | 10 | NR | NR |

| Rufián et al[39] | 33 | 1, 4 | NR | 46 | 37 |

| Raspagliesi et al[40] | 40 | 3, 5 | 11 | NR | 15 |

| Reichman et al[41] | 13 | 1, 4 | 15 | 55 | NR |

| Gori et al[42] | 29 | 3 | 571 | NR | NR |

| Look et al[43] | 28 | 1, 5 | 17 | NR | NR |

| Ryu et al[44] | 57 | 2, 3 | 26 | NR | 54 |

| Piso et al[45] | 19 | 1, 4, 5 | 18 | NR | 15 |

| Zanon et al[46] | 30 | 2 | 17 | 35 | 12 |

| Chatzigeorgiou et al[47] | 20 | 5 | 21 | NR | NR |

| de Bree et al[48] | 19 | 4, 5 | 26 | 63 | 42 |

| Cavaliere et al[49] | 20 | NR | NR | 502 | NR |

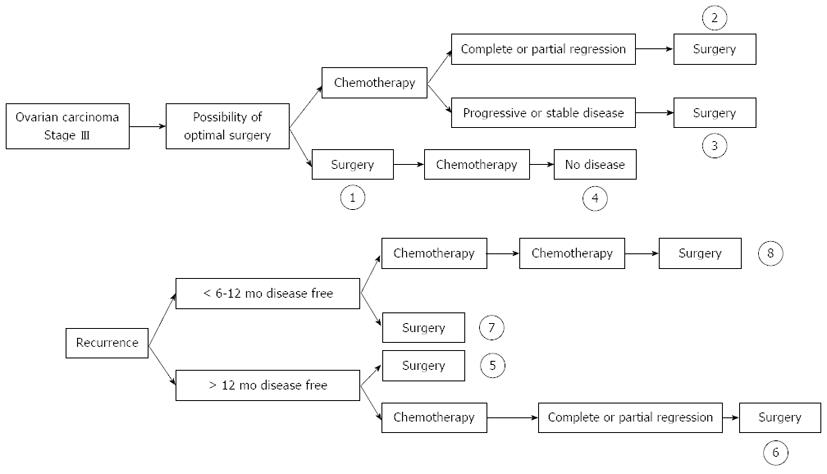

Given that chemo-sensitivity is an important issue for the prognosis and the homogeneity of these patients, we considered eight time-points upon which a clinical trial could be based: (1) time of primary treatment where optimal cytoreduction is achieved (group with chemo-sensitive and chemo-insensitive tumors); (2) time of IDS after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy with partial or complete response (chemo-sensitive group); (3) time of IDS after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy with stable disease (chemo-insensitive group); (4) time of consolidation therapy after complete pathological response following initial therapy (chemo-sensitive group); (5) time of first recurrence when disease relapses more than 12 mo after treatment (chemo-sensitive/chemo-insensitive group); (6) time of first recurrence when disease relapses more than 12 mo after treatment and a course of chemotherapy obtains complete response (chemo-sensitive group); (7) time of first recurrence when disease relapses less than 12 mo after treatment (chemo-insensitive group); and (8) time of salvage therapy after various chemotherapy lines (chemo-insensitive group) (Figure 2). Correct analysis of past and future clinical trials should take account of these time-points in patient evaluation.

P- Reviewers: de Andrade Urban C, Kruse AJ S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Hughes D E- Editor: Zheng XM

| 1. | Morrison J, Haldar K, Kehoe S, Lawrie TA. Chemotherapy versus surgery for initial treatment in advanced ovarian epithelial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD005343. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Fagotti A, Gallotta V, Romano F, Fanfani F, Rossitto C, Naldini A, Vigliotta M, Scambia G. Peritoneal carcinosis of ovarian origin. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:102-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Elattar A, Bryant A, Winter-Roach BA, Hatem M, Naik R. Optimal primary surgical treatment for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD007565. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:433-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1399] [Cited by in RCA: 1278] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. Pathogenesis of ovarian cancer: lessons from morphology and molecular biology and their clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:151-160. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Shih IeM, Kurman RJ. Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1511-1518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 873] [Cited by in RCA: 926] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Singer G, Stöhr R, Cope L, Dehari R, Hartmann A, Cao DF, Wang TL, Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. Patterns of p53 mutations separate ovarian serous borderline tumors and low- and high-grade carcinomas and provide support for a new model of ovarian carcinogenesis: a mutational analysis with immunohistochemical correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Bell DA. Origins and molecular pathology of ovarian cancer. Mod Pathol. 2005;18 Suppl 2:S19-S32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McCluggage WG. Morphological subtypes of ovarian carcinoma: a review with emphasis on new developments and pathogenesis. Pathology. 2011;43:420-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Borley J, Wilhelm-Benartzi C, Brown R, Ghaem-Maghami S. Does tumour biology determine surgical success in the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer? A systematic literature review. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1069-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Al Rawahi T, Lopes AD, Bristow RE, Bryant A, Elattar A, Chattopadhyay S, Galaal K. Surgical cytoreduction for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD008765. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hamilton CA, Miller A, Miller C, Krivak TC, Farley JH, Chernofsky MR, Stany MP, Rose GS, Markman M, Ozols RF. The impact of disease distribution on survival in patients with stage III epithelial ovarian cancer cytoreduced to microscopic residual: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:521-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Lang J, Huh J, Haddad L, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Levine DA, Hensley M, Barakat RR. What is the optimal goal of primary cytoreductive surgery for bulky stage IIIC epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC)? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:559-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Weinberg LE, Rodriguez G, Hurteau JA. The role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in treating advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:334-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jacob JH, Gershenson DM, Morris M, Copeland LJ, Burke TW, Wharton JT. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval debulking for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;42:146-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Neijt JP, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, van der Burg ME, van Oosterom AT, Willemse PH, Heintz AP, van Lent M, Trimbos JB, Bouma J, Vermorken JB. Randomized trial comparing two combination chemotherapy regimens (CHAP-5 v CP) in advanced ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1157-1168. [PubMed] |

| 17. | van der Burg ME, van Lent M, Buyse M, Kobierska A, Colombo N, Favalli G, Lacave AJ, Nardi M, Renard J, Pecorelli S. The effect of debulking surgery after induction chemotherapy on the prognosis in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecological Cancer Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Baergen R, Lele S, Copeland LJ, Walker JL, Burger RA. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2030] [Cited by in RCA: 1949] [Article Influence: 102.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hess LM, Benham-Hutchins M, Herzog TJ, Hsu CH, Malone DC, Skrepnek GH, Slack MK, Alberts DS. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of intraperitoneal cisplatin for the front-line treatment of ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:561-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Barlin JN, Dao F, Zgheib NB, Ferguson SE, Sabbatini PJ, Hensley ML, Bell-McGuinn KM, Konner J, Tew WP, Aghajanian C. Progression-free and overall survival of a modified outpatient regimen of primary intravenous/intraperitoneal paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:621-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ansaloni L, Agnoletti V, Amadori A, Catena F, Cavaliere D, Coccolini F, De Iaco P, Di Battista M, Framarini M, Gazzotti F. Evaluation of extensive cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:778-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ansaloni L, De Iaco P, Frigerio L. Re: “cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy as upfront therapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: multi-institutional phase II trial.” - Proposal of a clinical trial of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer, the CHORINE study. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:279-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Coccolini F, Lotti M, Manfredi R, Catena F, Vallicelli C, De Iaco PA, Da Pozzo L, Frigerio L, Ansaloni L. Ureteral stenting in cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy as a routine procedure: evidence and necessity. Urol Int. 2012;89:307-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rustin GJ, van der Burg ME. A randomized trial in ovarian cancer of early treatment of relapse based on CA125 level alone versus delayed treatment based on conventional clinical indicators (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955 trials). J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:18s. |

| 25. | Fulham MJ, Carter J, Baldey A, Hicks RJ, Ramshaw JE, Gibson M. The impact of PET-CT in suspected recurrent ovarian cancer: A prospective multi-centre study as part of the Australian PET Data Collection Project. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hall M, Rustin G. Recurrent ovarian cancer: when and how to treat. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13:459-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chua TC, Liauw W, Robertson G, Chia WK, Soo KC, Alobaid A, Al-Mohaimeed K, Morris DL. Towards randomized trials of cytoreductive surgery using peritonectomy and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for ovarian cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:137-19; author reply 139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Deraco M, Virzì S, Iusco DR, Puccio F, Macrì A, Famulari C, Solazzo M, Bonomi S, Grassi A, Baratti D. Secondary cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a multi-institutional study. BJOG. 2012;119:800-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chua TC, Yan TD, Saxena A, Morris DL. Should the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy still be regarded as a highly morbid procedure?: a systematic review of morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2009;249:900-907. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Pomel C, Ferron G, Lorimier G, Rey A, Lhomme C, Classe JM, Bereder JM, Quenet F, Meeus P, Marchal F. Hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy using oxaliplatin as consolidation therapy for advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Results of a phase II prospective multicentre trial. CHIPOVAC study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:589-593. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Bereder J, Glehen O, Habre J, Desantis M, Cotte E, Mounier N, Ray-Cocquard I, Karimdjee B, Bakrin N, Bernard J. Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer: a multiinstitutional study of 246 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5542. |

| 32. | Pavlov MJ, Kovacevic PA, Ceranic MS, Stamenkovic AB, Ivanovic AM, Kecmanovic DM. Cytoreductive surgery and modified heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for advanced and recurrent ovarian cancer -- 12-year single center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1186-1191. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Fagotti A, Paris I, Grimolizzi F, Fanfani F, Vizzielli G, Naldini A, Scambia G. Secondary cytoreduction plus oxaliplatin-based HIPEC in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer patients: a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:335-340. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Guardiola E, Delroeux D, Heyd B, Combe M, Lorgis V, Demarchi M, Stein U, Royer B, Chauffert B, Pivot X. Intra-operative intra-peritoneal chemotherapy with cisplatin in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of ovarian cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Di Giorgio A, Naticchioni E, Biacchi D, Sibio S, Accarpio F, Rocco M, Tarquini S, Di Seri M, Ciardi A, Montruccoli D. Cytoreductive surgery (peritonectomy procedures) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the treatment of diffuse peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:315-325. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Bae J, Lim MC, Choi JH, Song YJ, Lee KS, Kang S, Seo SS, Park SY. Prognostic factors of secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009;20:101-106. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Cotte E, Glehen O, Mohamed F, Lamy F, Falandry C, Golfier F, Gilly FN. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemo-hyperthermia for chemo-resistant and recurrent advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: prospective study of 81 patients. World J Surg. 2007;31:1813-1820. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Helm CW, Randall-Whitis L, Martin RS, Metzinger DS, Gordinier ME, Parker LP, Edwards RP. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in conjunction with surgery for the treatment of recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:90-96. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Rufián S, Muñoz-Casares FC, Briceño J, Díaz CJ, Rubio MJ, Ortega R, Ciria R, Morillo M, Aranda E, Muntané J. Radical surgery-peritonectomy and intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in recurrent or primary ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:316-324. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Raspagliesi F, Kusamura S, Campos Torres JC, de Souza GA, Ditto A, Zanaboni F, Younan R, Baratti D, Mariani L, Laterza B. Cytoreduction combined with intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion chemotherapy in advanced/recurrent ovarian cancer patients: The experience of National Cancer Institute of Milan. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:671-675. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Reichman TW, Cracchiolo B, Sama J, Bryan M, Harrison J, Pliner L, Harrison LE. Cytoreductive surgery and intraoperative hyperthermic chemoperfusion for advanced ovarian carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2005;90:51-56; discussion 56-58. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Gori J, Castaño R, Toziano M, Häbich D, Staringer J, De Quirós DG, Felci N. Intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:233-239. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Look M, Chang D, Sugarbaker PH. Long-term results of cytoreductive surgery for advanced and recurrent epithelial ovarian cancers and papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:35-41. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Ryu KS, Kim JH, Ko HS, Kim JW, Ahn WS, Park YG, Kim SJ, Lee JM. Effects of intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:325-332. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Piso P, Dahlke MH, Loss M, Schlitt HJ. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2004;2:21. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Zanon C, Clara R, Chiappino I, Bortolini M, Cornaglia S, Simone P, Bruno F, De Riu L, Airoldi M, Pedani F. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for recurrent peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. World J Surg. 2004;28:1040-1045. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Chatzigeorgiou K, Economou S, Chrysafis G, Dimasis A, Zafiriou G, Setzis K, Lyratzopoulos N, Minopoulos G, Manolas K, Chatzigeorgiou N. Treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer with secondary cytoreduction and continuous intraoperative intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion (CIIPHCP). Zentralbl Gynakol. 2003;125:424-429. [PubMed] |

| 48. | de Bree E, Romanos J, Michalakis J, Relakis K, Georgoulias V, Melissas J, Tsiftsis DD. Intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with docetaxel as second-line treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis of gynaecological origin. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3019-3027. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Cavaliere F, Di Filippo F, Botti C, Cosimelli M, Giannarelli D, Aloe L, Arcuri E, Aromatario C, Consolo S, Callopoli A. Peritonectomy and hyperthermic antiblastic perfusion in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:486-491. [PubMed] |