Published online Dec 28, 2023. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v12.i4.45

Peer-review started: October 5, 2023

First decision: October 9, 2023

Revised: November 4, 2023

Accepted: November 17, 2023

Article in press: November 17, 2023

Published online: December 28, 2023

Processing time: 83 Days and 16.7 Hours

Eclampsia is a generalized tonic-clonic seizure induced by pregnancy. It contri

A young primigravida experienced a generalised seizure without hypertension and/or proteinuria. Sudden hearing loss, blurred vision, and vomiting were complained about before the seizure attack. The patient was diagnosed with eclampsia. A loading dose of magnesium sulphate was administered imme

Atypical eclampsia may be a diagnostic challenge. However, other symptoms may be beneficial, such as awareness of eclampsia signs.

Core Tip: Generalized seizures are the hallmark of eclampsia, along with high blood pressure and proteinuria. However, in some women, eclampsia could develop in the absence of proteinuria and hypertension. A seizure in pregnancy without hypertension and/or proteinuria is considered atypical eclampsia. Here, we report an atypical presentation of eclampsia, the generalised seizure without prior hypertension and proteinuria, experienced by a young primigravida in a primary healthcare centre located in a remote area. We found neurological disturbances and gastrointestinal symptoms were present as impending eclampsia symptoms. Magnesium sulphate is administered as the first line of eclampsia treatment.

- Citation: Putri RWY, Mahroos RE. Atypical eclampsia at primary health care in a remote area: A case report. World J Obstet Gynecol 2023; 12(4): 45-50

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v12/i4/45.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v12.i4.45

Eclampsia is an emergency obstetric complication that is characterised by seizures accompanied by hypertension and proteinuria that occur during antepartum (over 20 wk of gestation), intrapartum, or postpartum (48 h post-delivery) and can lead to maternal morbidity and death[1]. In a rare case, eclampsia can present as atypical, which refers to eclamptic seizures that happen without usual high blood pressure (BP) or proteinuria. A seizure that occurs < 20 wk after gestation or > 48 h after childbirth is another atypical feature of eclampsia[2].

Rural and remote communities often encounter more healthcare barriers that limit their access to the necessary healthcare services they need. Poor access to advanced healthcare facilities and limited resources in primary healthcare centres are two main reasons for inadequate healthcare delivery. Furthermore, this became a challenge for healthcare providers in order to provide appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Raising awareness of the uncommon presentation of eclampsia may enhance clinical management, especially in rural areas and other limited-resource primary healthcare services.

A 22-year-old, 39-wk-old primigravida (G1P0A0) Asian woman complained of vomiting followed by sudden visual and hearing disturbances, and a generalised seizure.

A young nulliparous woman was admitted to the primary healthcare centre due to true labour clinical manifestations, regular contractions, and a small amount of blood and mucus released from the vagina. During stage 2 of labour, an episodic tonic-clonic seizure was present for around 1 min. Sudden visual disturbances, vomiting, and hearing disturbances were complained about by the patient immediately before the seizure.

The patient had no history of seizures or hypertension before pregnancy and/or during antenatal care. Our patient had no past head trauma or illnesses such as hypertension, epilepsy, metabolic diseases, autoimmune disease, infection, stroke, severe headache, or cancer. A history of medication was also denied. The patient had routine antenatal care in a primary healthcare facility and vaccination for tetanus and coronavirus disease 2019. The patient’s general conditions, vital signs, proteinuria, weight gain, and foetal conditions were examined through regular antenatal visits and showed no abnormalities.

Relevant personal and family histories were denied. Family history of seizure, hypertension, eclampsia, and pre-eclampsia were absent.

At stage 1 of labour, the normal-weight patient was conscious and in good general condition; thus, a physical examination was performed. On admission, it was reported that her supine blood pressure (BP) was 112/70 mmHg, heart rate (HR) 76 beats/min, respiratory rate (RR) 20 breaths/min, temperature 36.8℃, and oxygen saturation 98% in room air. Cephalic proportion, normoregular foetal HR, 1 cm cervical dilatation, and adequate uterine contraction were also reported. Extremity and lung oedema manifestations were absent. Other physical examinations were normal. Vital signs, progress of labour, and foetal HR were monitored every 4 h. During monitoring, the partograph curve and vital signs were within normal ranges. Systolic BP was 110-124 mmHg, and diastolic BP was 72-80 mmHg.

The patient experienced a prolonged second stage of labour due to inadequate power, thus complaining of vomiting, blurred vision, and hearing disturbances followed immediately by a tonic-clonic seizure. Vital signs and foetal HR were re-evaluated. The latest supine BP was 128/72 mmHg, HR 80 beats/min, RR 18 breaths/min, temperature 36.9℃, and oxygen saturation 96% in room air. We found no abnormalities on physical and neurological examinations.

This case was first found in a limited-resource primary healthcare setting where there was no laboratory facility, so only simple traditional laboratory examinations could be performed through strip tests. Stick haemoglobin 12.8 g/dL, stick random blood glucose 110 mg/dL, negative rapid test human immunodeficiency virus, and negative proteinuria (dipstick) were reported.

Imaging examinations such as brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and brain computed tomography (CT) scan could not be performed because of absence of equipment.

Susanto Rahmad, MD, obstetrician and gynaecologist.

Eclampsia in primigravida patient.

Treatment with 4 g intravenous MgSO4 was given immediately as a loading dose, followed by 2 g intravenous MgSO4 dissolved in 500 mL crystalloid (normal saline) at a rate of 28 drops/min. A urine catheter and 3 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula were administered. We did not give antihypertensive medication because the patient’s BP was normal.

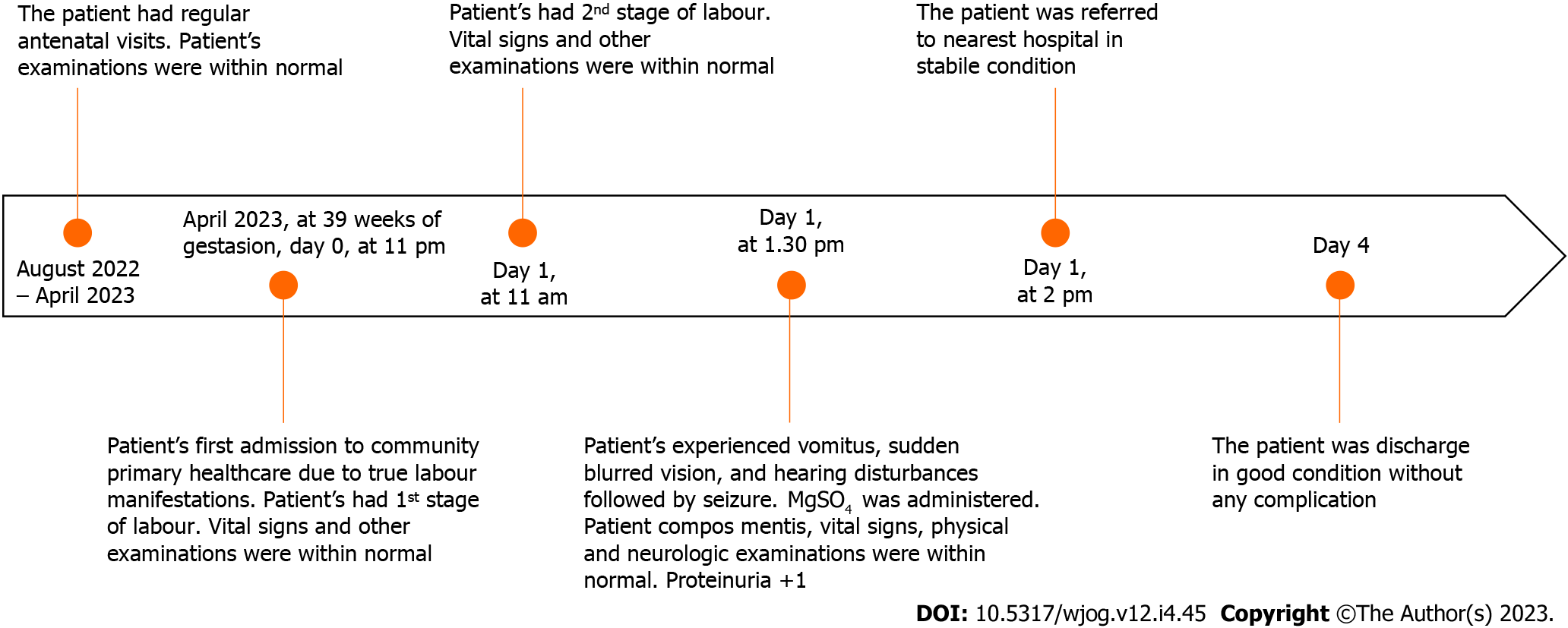

The seizure did not relapse after immediate treatment was given. Vomiting and visual and hearing disturbances were also relieved after treatment. Vital signs were re-evaluated after treatment: supine BP 110/75 mmHg, HR 75 beats/min, RR 21 breaths/min, temperature 36.9℃, and oxygen saturation 98% with 3 L/min oxygen administered by nasal cannula. Around 50 mL urine output and 1+ proteinuria (30-100 mg/dL) were present in the urine examination. The complete blood test was not carried out due to limited laboratory facilities. Subsequently, the patient was referred to the hospital in a conscious and stable condition. The patient’s condition and vital signs were re-evaluated every 1 h after treatment was given until they arrived at the hospital: Systolic BP was 128-123 mmHg, diastolic BP 71-85 mmHg, HR 95 beats/min, RR 20-22 breaths/min, temperature 36.8℃, and oxygen saturation 97%-98%. The patient’s follow-up during hospitalisation could not be obtained due to incomplete medical record documentation. The patient was discharged in healthy condition from the hospital 3 d later, and a healthy 2.8-kg baby was born by vaginal delivery. The complete timeline of the patient’s condition is shown in Figure 1.

Elevated BP during pregnancy is considered one of the five leading causes of maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide. The global report that was analysed by the World Health Organization showed that around 343 000 maternal mortalities from 2003 to 2009 were caused by hypertension, and it was the second most common direct cause of maternal death (14%) after haemorrhage (26.1%). The incidence of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia was also higher in low- and low-to-middle-income countries. In Indonesia, the incidence of eclampsia was 128.753 per annum[3].

Eclampsia is defined as one of the hypertensive disorders related to pregnancy that is characterised by eclamptic seizures, an episodic general tonic-clonic seizure, followed by classic pre-eclampsia features such as hypertension (≥ 140 systolic BP and/or ≥ 90 diastolic BP), proteinuria (≥ 30 mg/dL), and/or organ damage (liver or renal dysfunction, low platelet, lung oedema, haemolysis, and unconscious) between 20-wk gestation and 48-h post-delivery. In rare, atypical cases, a pregnant woman may experience pre-eclampsia and/or eclampsia without either hypertension or proteinuria. However, other clinical manifestations such as severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, mucosal bleeding, and severe headache may present in atypical pre-eclampsia eclampsia[4]. A systematic review also reported that visual disturbance (27%), headache (66%), and epigastric pain (25%) are common symptoms, followed by eclampsia[5,6]. Our patient also experienced sudden persistent hearing loss, blurred vision, and vomiting without prior high BP and proteinuria.

New-onset seizures in pregnant women can be difficult and challenging to differentiate between eclampsia and other aetiologies. Eclampsia without classical signs may lead to unawareness of the diagnosis and delay in necessary treatment. Further examination, such as deeper physical examination, laboratory examination, and neuroimaging (head CT scan or MRI), should be carried out carefully to determine the underlying aetiology of the seizure attack, such as epilepsy, brain injury (ischemic or haemorrhagic), meningoencephalitis, hypoglycaemia, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome[6]. In addition, a multidisciplinary approach may be required to diagnose appropriately. Our patient denied any history of trauma or past illnesses. In addition, physical and neurological examinations were also normal. Unfortunately, this case occurred in a remote area with limited resources, so required neuroimaging and laboratory work could not be performed.

Eclampsia can develop before, during or after delivery. Based on gestational age, it can occur at < 34 wk gestation (early) and ≥ 34 wk gestation (late). In a comparative study, pre- and antepartum eclampsia were found more often in young (< 25 years old) nulliparous rather than multiparous women[7]. Similarly, a 6-year cohort study also reported that anaemia, obesity, nulliparity, and history of heart disease may be potential risks for eclampsia development[8]. These findings were in line with the characteristics of the patient in this study, a 22-year-old primigravida.

Based on guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, women with a history of hypertensive disease during previous pregnancy, autoimmune disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic hypertension, and diabetes would have a higher risk of developing pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. In addition, other conditions such as obesity, nulliparity, age ≥ 40 years, ≥ 10 years pregnancy interval, and multiple pregnancies could also increase the risk of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia[9].

The mechanism underlying eclampsia has been widely studied. Early onset of pre-eclampsia eclampsia is suggested to develop from placenta abruption, while late onset of pre-eclampsia eclampsia is suggested to develop from placenta senescence and the mother’s genetic predisposition to metabolic and cardiovascular diseases[10]. Disruption of placental blood flow causes a decrease in uteroplacental perfusion, thus inducing oxidative stress due to hypoxia and vascular endothelial dysfunction. The alteration of the placenta led to antiangiogenic factors and other inflammatory releases. In addition, the renin-angiotensin II axis, immune maladaptation, and genetics may also have roles in pre-eclampsia pathogenesis[11] (Figure 2).

Eclampsia is a life-threatening event during pregnancy or labour. Immediate treatment should be administered by a physician to prevent worse outcomes for both the mother and the baby. MgSO4 is a first-line drug to control and/or prevent convulsions in pre-eclampsia eclampsia treatment. The loading dose of MgSO4 is intravenous 4-6 g given in 15-20 min, followed by 1-2 g/h MgSO4 administered by infusion. Patella reflexes, urine output, and vital signs should be well-monitored after magnesium treatment in order to detect its toxicity early[12]. Oxygen supplementation at 8-10 L/min can be administered to maintain oxygenation, particularly during convulsive episodes. In addition, antihypertensive agents must be given to treat hypertensive emergencies (systolic BP ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 110 mmHg). Guideline recommendation of acute first-line antihypertensive medication includes labetalol 20 mg intravenously followed by 20-80 mg at 10-min intervals, hydralazine 5-10 mg intravenously followed by 10 mg at 20-min intervals, and nifedipine 10 mg orally and repeated every 30-min for 50 mg maximum dose in 1 h. The next step of eclampsia management is to deliver the baby within 24 h of eclampsia onset[6].

Hypertension, proteinuria, and generalised seizures are the hallmarks of eclampsia. However, some pregnant women may experience atypical features of eclampsia, and eclamptic seizures without a prior history of high BP and proteinuria. The absence of these classic signs may lead to physician unawareness of pre-eclampsia eclampsia and become a diagnostic challenge. However, other symptoms, such as neural disturbances and gastrointestinal manifestations, may present as signs of impending eclampsia. In addition, deeper anamnesis and the required physical examination would be tremendously helpful for the physician in order to properly diagnose during work in a limited-facility setting.

The authors thank to Pejawaran Primary Public Health Center that providing this case.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Han J, China S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Timothy Miller, Ozlem Uzuner, Matthew M Churpek, Majid Afshar. A scoping review of publicly available language tasks in clinical natural language processing. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2022;29:1797-1806. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Modzelewski J, Siarkowska I, Pajurek-Dudek J, Feduniw S, Muzyka-Placzyńska K, Baran A, Kajdy A, Bednarek-Jędrzejek M, Cymbaluk-Płoska A, Kwiatkowska E, Kwiatkowski S. Atypical Preeclampsia before 20 Weeks of Gestation-A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, Gülmezoglu AM, Temmerman M, Alkema L. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323-e333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4232] [Cited by in RCA: 3501] [Article Influence: 318.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sibai BM, Stella CL. Diagnosis and management of atypical preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:481.e1-481.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fishel Bartal M, Sibai BM. Eclampsia in the 21st century. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:S1237-S1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hart LA, Sibai BM. Seizures in pregnancy: epilepsy, eclampsia, and stroke. Semin Perinatol. 2013;37:207-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Berhan Y, Endeshaw G. Clinical and Biomarkers Difference in Prepartum and Postpartum Eclampsia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25:257-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu S, Joseph KS, Liston RM, Bartholomew S, Walker M, León JA, Kirby RS, Sauve R, Kramer MS; Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada). Incidence, risk factors, and associated complications of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:987-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG133]. June 25, 2019. [cited 17 April 2023]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133. |

| 10. | Burton GJ, Redman CW, Roberts JM, Moffett A. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ. 2019;366:l2381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 108.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang A, Rana S, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia: the role of angiogenic factors in its pathogenesis. Physiology (Bethesda). 2009;24:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wilkerson RG, Ogunbodede AC. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019;37:301-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |