Peer-review started: March 17, 2016

First decision: April 19, 2016

Revised: April 28, 2016

Accepted: May 31, 2016

Article in press: June 2, 2016

Published online: June 28, 2016

Processing time: 101 Days and 7.8 Hours

The primary purpose of this article was to review the current literature regarding the clinical consequences of centipede envenomation in humans, in order to determine whether the bite of these arthropods is neurotoxic to humans or not. A thorough search of the literature regarding the clinical consequences of centipede bites in humans was applied, with great respect to neurological symptoms potentially caused by such bites. Centipede bite commonly causes only local reactions, which usually resolve within a few days without sequelae. The patients in the majority of centipede envenomations describe a painful but benign syndrome. However, mild constitutional symptoms are relatively frequent. Remarkably, centipedes can rarely cause severe systematic reactions such as anaphylaxis or even hypotension and myocardial ischemia. Factors such as patient age, comorbidity, anatomic site of envenomation, and size/species of centipede should be considered when evaluating a centipede envenomation victim. According to the current literature, the centipede bite does not seem to be neurotoxic to humans. However, it commonly causes symptoms mediated by the nervous system. These include local and generalized symptoms, with the first dominated by sensory disturbances and the second by non-specific symptoms such as headache, anxiety and presyncope. Based on our results, the answer to our study’s question is negative. The centipede bite is not neurotoxic to humans. However, it commonly causes symptoms mediated by the nervous system, which include primarily local pain and sensory disturbances, as well as generalized non-specific symptoms such as headache, anxiety and vagotonia.

Core tip: Centipede bite commonly causes only local reactions, which usually resolve within a few days without sequelae. The patients in the majority of cases describe a painful but benign syndrome. Mild constitutional symptoms are relatively frequent, whereas severe systematic reactions, such as anaphylaxis, hypotension and even myocardial ischemia, are rare. According to the current literature, the centipede bite does not seem to be neurotoxic to humans. However, it commonly causes symptoms mediated by the nervous system. These include local and generalized symptoms, with the first dominated by sensory disturbances and the second by non-specific symptoms such as headache, anxiety and vagotonia.

- Citation: Mavridis IN, Meliou M, Pyrgelis ES. Clinical consequences of centipede bite: Is it neurotoxic? World J Neurol 2016; 6(2): 23-29

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6212/full/v6/i2/23.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5316/wjn.v6.i2.23

Taxonomy: Centipedes are invertebrate animals belonging to phylum Arthropoda, class Chilopoda and subphylum Myriapoda[1,2]. Although over 8000 species are estimated to exist worldwide, only 3000 have been described, in habitats varying from deserts to the Arctic[3]. There are four major orders (all venomous) of centipedes: Geophilomorpha (innocuous soil dwellers, small), Scolopendramorpha (giant or tropical centipedes-known stingers), Scutigeramorpha (fast but delicate house centipedes) and Lithobiomorpha (garden or rock centipedes-resemble small scolopendramorpha in appearance with many anecdotal reports of stings)[2].

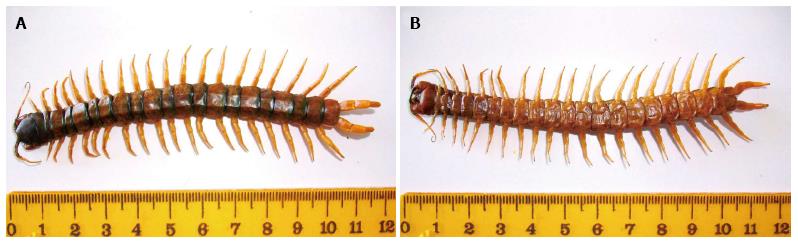

Morphology: Centipedes are distinguishable from insects by their many (from less than 20 to more than 300) legs (at least nine pairs) and by their largely uniform bodies (not divided into head, thorax and abdomen)[4]. They are slender, multisegmented arthropods characterized by one pair of legs on each body trunk segment[1,2] and one pair of antennae. Their coloration may range from bright yellow to brown-black (Figure 1). They have two sharp stinging structures connected to muscular venom glands and these structures constitute actually the modified first pair of centipede legs[2]. These venomous fangs, their key characteristic, are their hunting and defensive equipment[1].

Centipedes range in length between 0.05-30 cm[2,4] and the common centipede is usually 2-3 cm long[4]. The Scolopendra are the largest centipedes, probably the most venomous and therefore the most dangerous. They range between 8-15 cm in length (Figure 1), and Scolopendra heros (S. heros) can achieve lengths of more than 20 cm[2]. Giant centipedes are found in a few places including Africa (Scolopendra spp.)[4], New Guinea (Scolopendra morsitans and subspinipes)[5] and Philippine Islands (Scolopendra subspinipes)[6]. Scolopendra usually have a yellow-brown body with orange and blue cephalic/caudal parts[2] (Figures 1 and 2).

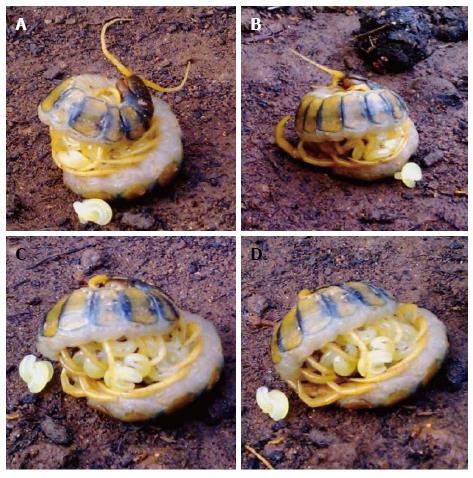

Habitation: Centipedes have a worldwide distribution and are well represented in Europe and Africa[2,4]. They are found in wild habitats, warm temperate and tropical climates, but also in gardens[2,4]. They are found mainly in soil (Figure 2) and litter and prefer dark damp environments, such as below rocks and logs[1,2,7]. Common centipede hides by day in crevices, such as under loose bark, leaves or stones[4]. Centipedes can sometimes be found inside sheds or even enter houses, especially in wet weather (rainy days)[2,4], thus constituting common household arthropods[8].

Centipedes are nocturnal carnivores with a wide range of prey[2,4,7]. Centipedes emerge at night to hunt primarily for insect larvae (crickets, cockroaches) and occasionally for slugs, worms, small snakes and even small mammals, catching them using their powerful venomous fangs[2,4]. These fast-moving arthropods use their venom to paralyze prey prior to eating[2]. Ants and termites are, among other animals, their natural predator[7].

The purpose of this article is to review the current literature regarding the clinical consequences of centipede envenomation in humans, searching for neurological symptoms that could be potentially caused by centipede bites. Thus, with this review, we aimed to determine whether the bite of these arthropods is neurotoxic to humans or not. As “neurotoxins” we considered all venom components affecting the nervous system, not only those causing serious and lethal consequences (e.g., paralyzing agents) but also those having a milder and temporal effect (e.g., pain-inducing agents).

A careful and thorough search of the English language literature, regarding all the clinical consequences of centipede bites in humans, was applied with great respect to neurological symptoms potentially caused by such bites. For a comprehensive review of existing data Pubmed was searched using the following terms: “centipede bite” and “symptoms”. The available data are restricted and most relevant information is provided by articles reporting cases of centipede envenomation in humans and its management.

Centipedes may display aggressive behavior[2]. Although their bites are not rare, few studies have evaluated the effects of centipede venom in humans and the literature over this issue is limited[2]. The lack of basic knowledge on venomous arthropods and the usually benign clinical course contribute to the frequent care of centipede bite victims at home (instead of a treatment reference center), leading to underestimation of the number of cases[9].

In a remarkable number of cases (63%) who seek medical care, victims bring the agent in for identification. The genera most frequently reported to bite humans include Cryptops (58%), Otostigmus (33%) and Scolopendra (4%)[9]. There is a predominance of accidents in the warm rainy season [reproductive period of the centipede (Figure 2), associated with their sinanthropic habits], in the morning hours and also among females[9] and ages between 20-60 years[9,10]. Centipede bites often occur as the victim is dressing or while in bed[2]. Upper and lower extremities are the parts of the body most commonly affected[9].

A centipede bite is an injury resulting from the action of centipede’s forcipules, pincer-like appendages that pierce the skin and inject venom into the wound, which is not actually a bite, as the forcipules are modified legs rather than true mouthparts[11]. Despite some reports of tenacious attachments requiring removal with a noxious agent (e.g., alcohol) or even surgery, centipedes tend to release from the skin immediately[2].

The complete mechanism of centipede venom toxicity is not yet completely understood[12] and this venom, as well as the venom apparatus of centipedes, remains largely unexplored[13,14]. It contains several different enzymes, but is different to most other arthropods in that metalloproteases appear to be important. Cardiotoxic, myotoxic and neurotoxic activities have been described, with the latter being unusual in the fact of involvement of G-protein coupled receptors, directly as neurotoxin-targets or indirectly by activation of endogenous agonists[14]. Noteworthy, the contents of approximately 1000 venom glands are required for a fatal sting in an average adult[2].

More specifically, the venom from Scolopendra species is a lipid-toxin complex, similar to that of scorpion, which facilitates local cellular penetration and absorption[2]. Its compounds include 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), histamine and cardiodepressant Toxin-S, mediating significant cardiovascular effects, a smooth muscle contractile agent with muscarinic activity, proteinases and lipoproteins[2,12]. S. heros contains also a cytolysin potentiating both its local and systemic effects.

The Chinese red-headed centipede (Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans) is a venomous centipede found in East Asia and Australasia[15] and its venom contains 26 neurotoxin-like peptides[13]. Several of these neurotoxins contain potential insecticidal abilities, and they act on voltage-gated Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels[13]. Among them, neurotoxin SsmTx-I blocks voltage-gated K+ channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons, but has no effect on voltage-gated Na+ channels[15]. Moreover peptide μ-SLPTX-Ssm6a inhibits voltage-gated Na+ channels and is more potent analgesic than morphine in rodents[16]. Finally, toxin RhTx induces pain and targets the heat activation machinery (potently activates the capsaicin receptor TRPV1) to produce excruciating pain[17].

Centipede bite commonly causes only local reactions[8], which usually resolve within a few days without sequelae (excluding local skin necrosis)[2]. Skin reactions at the bite site are the commonest symptom after a centipede attack on humans[18]. Clinically, the wound is viewed as a cutaneous lesion characterized by two hemorrhagic marks forming a chevron shape caused by the large paired forcipules of the centipede[11]. Local reactions include intense worsening local pain[2,4,9,10,18-23] of sudden onset or even lingering ‘‘dull’’ pain at the sting site[2], edema[2,4,9,10,18,21-24] (severe edema is mostly observed in cases of bites by Otostigmus spp.[19]), erythema[2,9,18,19,21-24], transient hemorrhagic oozing from the puncture site[9,25], itchiness[22], burning sensation[9,25], induration[2], numbness and tingling, extraordinary tenderness (on physical examination), throbbing[2,25] and paresthesias[20,25], lymphangitis/lymphadenitis, local infection[25] or necrosis[2,25] and development of a red streak at the skin[2]. Hemorrhagic vesicles and blisters formation is described less often[12,18,26,27]. Limited range of motion or even weakness, reduction of flexibility and severe ‘‘sprained’’ sensation at the affected limb have been also reported[2].

Severe skin reactions are rare[28]. Abscess formation[20] and late development (within days or even weeks) of local necrotic area or recurrence of swelling with intense local itching (pruritus) may occur at the site of envenomation[2]. Cases of severe local toxicity and bacterial infection (usually from Gram positive cocci) have been also described[28]. Some cases even lead to cellulitis and necrotic fasciitis of the bite region[28], usually a limb that if left untreated could lead to amputation.

Common effects of centipede bites may include mild constitutional symptoms which usually resolve without sequelae[2]. These include headache[9,12], anxiety, (low) fever, dizziness, chest discomfort or pain, near syncope, palpitations, nausea, vomiting, general feeling of unwellness, flushing, writhing, sharp pain at various body areas and restlessness secondary to the pain[2,12]. Constitutional upset occurs in a small minority[25].

It is known that centipedes, among other insects, can cause not only local but also systematic clinical effects such as anaphylaxis or even hypotension and myocardial ischemia (from vasospasm and myocardial toxic effects of the venom)[29]. The toxins released with envenomation cause vagal activity which could result in circulatory symptoms. Histamine and Toxin S are considered as mediators for myocardial injury[30]. Cases of acute myocardial ischemia have been described following a centipede bite, either as presenting manifestation[25] or following local symptoms[29,31].

Furthermore, sensitivity reactions are not uncommon, although late hypersensitivity reaction is described less often[12]. Immediate type allergic reaction against centipede venom has been reported, with dyspnea, general fatigue and urticaria and positive prick test. Some relationship between centipede allergy and bee allergy has been supported[32]. An immune complex deposition syndrome (type III hypersensitivity reaction) manifesting as recurrence of swelling associated with pruritus at the sting sites, has been further suggested[2].

Proteinuria, usually in the context of nephritic syndrome[33], as well as extensive myonecrosis with subsequent compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure may rarely occur due to centipede bite[2,34].

Other very rare clinical consequences following centipede bite include psychological disturbances and Korsakoff syndrome (Japanese Scolopendra species)[2], Wells’ syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis)[35] and pericoronitis[36]. The patient may rarely feel fine (almost ‘‘euphoric’’) a few hours after the bite[2]. Irritability and uncontrollable cry (beside local symptoms) have been reported in neonates[37] and systemic side effects (due to systemic absorption of the venom) in infants, requiring, though, no active intervention[8]. Remarkably, a fatality has been reported following a sting by a large specimen of S. subspinipes to the head of a small Filipino child[2]. Finally, there is also a report of postmortem injury (subcutaneous cavity on the victim’s forearm) caused by a centipede[38].

Differential diagnosis from snake (especially viper) bites is essential in regard to treatment strategy. The length of the biting animal (2-30 cm for centipedes), the bite mark characteristics (pointed in shape for centipedes), the presence of hemorrhagic vesicles, the progression of local reactions (usually remaining localized to a 10 cm × 10 cm area of involvement), as well as the wound size, are useful in the differentiation between centipede and viper bites in clinical practice[39].

The majority of centipede envenomation victims describe a painful but benign syndrome[2]. The clinical course following most centipede stings appears self-limited (resolving within hours to few days[2,10]) and rarely associated with any serious consequences[2]. Even though prognosis of centipede bites is usually benign, presence of underlying disease could complicate the course of therapy[40]. For example, underlying diabetes mellitus could complicate the course of the disease with more severe skin reactions and infections[12]. In the interesting case described by Rouvin et al[40], the patient, an heterozygotous for sickle cell disease female, suffered a prolonged and severe course of disease after a centipede sting.

Despite the striking appearance of the offender and the significant pain associated with its sting[2], the benign evolution of the clinical picture makes often therapeutic treatment unnecessary[9]. Supportive treatment is usually enough for the symptoms of centipede bite victims to resolve within hours to few days and without any sequelae[2,10]. This includes pain control, wound care and tetanus immunization[2]. Pain-relief is the cornerstone of treatment[25] and analgesics (such as paracetamol) are usually administered[18]. Additionally, local anesthetics, systemic (such as prednisone[18]) and/or topical corticosteroids, antihistamines and administration of a biscoclaurin alkaloid may be considered, as needed according to the severity of the lesions[9,24]. Factors such as patient age and comorbid conditions, anatomic site of envenomation, and size/species of centipede should be considered when evaluating a patient with a centipede envenomation[2]. Noteworthy, therapeutical treatment is a rule for the victims of Scolopendra and Otostigmus[9].

Although the centipedes’ venom contains neurotransmitters (serotonin, histamine) and agents affecting the autonomic nervous system (smooth muscle contractile agent with muscarinic activity)[2,12], its clinical effects are not primarily of neurological nature. Despite this observation there are some common symptoms mediated by the nervous system. Local neurological symptoms are mainly sensory disturbances and include acute pain[2,4,9,10,18,19-23], lingering ‘‘dull’’ pain[2], paresthesias[20,25] such as burning sensation[9,25], numbness and tingling (with extraordinary tenderness on clinical examination)[2,25], and severe ‘‘sprained’’ sensation at the affected limb[2]. Weakness has been reported but it seems to be probably due to the reduction of flexibility and limited range of motion of the affected limb[2]. Generalized neurological symptoms include headache[9,12], anxiety, dizziness and presyncope (vagotonia[30]), flushing, sharp pain at various body areas and restlessness secondary to the pain[2,12]. Unusual neuropsychiatric symptoms may also occur in centipede bite victims and include nearly ‘‘euphoric’’ feeling (a few hours following the bite), psychological disturbances and Korsakoff syndrome[2]. Table 1 summarizes the commonest neurological symptoms caused by centipede bite in humans.

| Local |

| Pain (sharp, dull) |

| Paresthesias (numbness, tingling, burning sensation) |

| Weakness |

| Generalized |

| Headache |

| Anxiety |

| Presyncope (vagotonia) |

| Sharp pain at various body areas |

| Flushing |

Given that, to the best of our knowledge, the centipede venom does not cause damage to nervous tissue and that the above-mentioned neurological symptoms are transient, the answer to our study’s question is negative. The centipede bite is not neurotoxic to humans. However, it commonly causes symptoms mediated by the nervous system. These include local and generalized, with the first dominated by sensory disturbances and the second by non-specific symptoms such as headache, anxiety and presyncope. In rare cases, severe neuropsychiatric conditions such as Korsakoff syndrome can be observed.

Centipede bite commonly causes only local reactions, which usually resolve within a few days without sequelae. The patients in the majority of centipede envenomation cases describe a painful but benign syndrome. However, mild constitutional symptoms are relatively frequent and severe systematic clinical effects such as anaphylaxis and myocardial ischemia may rarely be observed. Factors such as patient age and comorbid conditions, anatomic site of envenomation, and size/species of centipede should always be considered when evaluating a patient with a centipede envenomation. According to the current literature, the centipede bite does not seem to be neurotoxic to humans. However, it commonly causes symptoms mediated by the nervous system. These include primarily local pain and sensory disturbances, as well as generalized non-specific symptoms such as headache, anxiety and vagotonia.

P- Reviewer: Veraldi S, Zheng J S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Lewis JGE. The Biology of Centipedes. 1st ed. New York: Cambridge University Press 2007; . |

| 2. | Bush SP, King BO, Norris RL, Stockwell SA. Centipede envenomation. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001;12:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Adis J, Harvey MS. How many Arachnida and Myriapoda are there worldwide and in Amazonia? Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment. 2000;35:139-141. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Walters M. The Illustrated World Encyclopedia of Insects. Leicestershire: Lorenz Books-Anness Publishing 2012; 130-131. |

| 5. | Haneveld GT. [The bite of the giant New Guinea centipede (Scolopendra morsitans and subspinipes)]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1956;100:2906-2909. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Remington CL. The bite and habits of a giant centipede (Scolopendra subspinipes) in the Philippine Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1950;30:453-455. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Dejean A, Lachaud JP. The hunting behavior of the African ponerine ant Pachycondyla pachyderma. Behav Processes. 2011;86:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Barnett PL. Centipede ingestion by a six-month-old infant: toxic side effects. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1991;7:229-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Knysak I, Martins R, Bertim CR. Epidemiological aspects of centipede (Scolopendromorphae: Chilopoda) bites registered in greater S. Paulo, SP, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 1998;32:514-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Barroso E, Hidaka AS, dos Santos AX, Matos França JD, de Sousa AM, Rodrigues Valente J, Amoras Magalhães AF, Oliveira Pardal PP. [Centipede stings notified by the “Centro de Informações Toxicológicas de Belém”, over a 2-year period]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2001;34:527-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier 2006; . |

| 12. | Fung HT, Lam SK, Wong OF. Centipede bite victims: a review of patients presenting to two emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17:381-385. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Yang S, Liu Z, Xiao Y, Li Y, Rong M, Liang S, Zhang Z, Yu H, King GF, Lai R. Chemical punch packed in venoms makes centipedes excellent predators. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:640-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Undheim EA, King GF. On the venom system of centipedes (Chilopoda), a neglected group of venomous animals. Toxicon. 2011;57:512-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Chen M, Li J, Zhang F, Liu Z. Isolation and characterization of SsmTx-I, a Specific Kv2.1 blocker from the venom of the centipede Scolopendra Subspinipes Mutilans L. Koch. J Pept Sci. 2014;20:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Yang S, Xiao Y, Kang D, Liu J, Li Y, Undheim EA, Klint JK, Rong M, Lai R, King GF. Discovery of a selective NaV1.7 inhibitor from centipede venom with analgesic efficacy exceeding morphine in rodent pain models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17534-17539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yang S, Yang F, Wei N, Hong J, Li B, Luo L, Rong M, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Zheng J, Wang K. A pain-inducing centipede toxin targets the heat activation machinery of nociceptor TRPV1. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Veraldi S, Cuka E, Gaiani F. Scolopendra bites: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:869-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Medeiros CR, Susaki TT, Knysak I, Cardoso JL, Málaque CM, Fan HW, Santoro ML, França FO, Barbaro KC. Epidemiologic and clinical survey of victims of centipede stings admitted to Hospital Vital Brazil (São Paulo, Brazil). Toxicon. 2008;52:606-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Acosta M, Cazorla D. [Centipede (Scolopendra sp.) envenomation in a rural village of semi-arid region from Falcon State, Venezuela]. Rev Invest Clin. 2004;56:712-717. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Bouchard NC, Chan GM, Hoffman RS. Vietnamese centipede envenomation. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2004;46:312-313. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Balit CR, Harvey MS, Waldock JM, Isbister GK. Prospective study of centipede bites in Australia. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42:41-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McFee RB, Caraccio TR, Mofenson HC, McGuigan MA. Envenomation by the Vietnamese centipede in a Long Island pet store. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40:573-574. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Mohri S, Sugiyama A, Saito K, Nakajima H. Centipede bites in Japan. Cutis. 1991;47:189-190. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Uppal SS, Agnihotri V, Ganguly S, Badhwar S, Shetty KJ. Clinical aspects of centipede bite in the Andamans. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38:163-164. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Chaou CH, Chen CK, Chen JC, Chiu TF, Lin CC. Comparisons of ice packs, hot water immersion, and analgesia injection for the treatment of centipede envenomations in Taiwan. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47:659-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Veraldi S, Chiaratti A, Sica L. Centipede bite: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:807-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Uzel AP, Steinmann G, Bertino R, Korsaga A. [Necrotizing fasciitis and cellulitis of the upper limb resulting from centipede bite: two case reports]. Chir Main. 2009;28:322-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Senthilkumaran S, Meenakshisundaram R, Michaels AD, Suresh P, Thirumalaikolundusubramanian P. Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction from a centipede bite. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2011;2:244-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Yildiz A, Biçeroglu S, Yakut N, Bilir C, Akdemir R, Akilli A. Acute myocardial infarction in a young man caused by centipede sting. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ozsarac M, Karcioglu O, Ayrik C, Somuncu F, Gumrukcu S. Acute coronary ischemia following centipede envenomation: case report and review of the literature. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004;15:109-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Harada S, Yoshizaki Y, Natsuaki M, Shimizu H, Fukuda H, Nagai H, Ikeda T. [Three cases of centipede allergy--analysis of cross reactivity with bee allergy]. Arerugi. 2005;54:1279-1284. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Hasan S, Hassan K. Proteinuria associated with centipede bite. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:550-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Logan JL, Ogden DA. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure following the bite of the giant desert centipede Scolopendra heros. West J Med. 1985;142:549-550. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Friedman IS, Phelps RG, Baral J, Sapadin AN. Wells’ syndrome triggered by centipede bite. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:602-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gelbier S, Kopkin B. Pericoronitis due to a centipede. A case report. Br Dent J. 1972;133:307-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Rodriguez-Acosta A, Gassette J, Gonzalez A, Ghisoli M. Centipede (Scolopendra gigantea Linneaus 1758) envenomation in a newborn. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2000;42:341-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Harada K, Asa K, Imachi T, Yamaguchi Y, Yoshida K. Centipede inflicted postmortem injury. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44:849-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lin TJ, Yang CC, Yang GY, Ger J, Tsai WJ, Deng JF. Features of centipede bites in Taiwan. Trop Geogr Med. 1995;47:300-302. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Rouvin B, Seck M, N’diaye M, Diatta B, Saissy JM. [Centipede bite in a woman with heterozygotous sickle cell disease]. Med Trop (Mars). 2008;68:647-648. [PubMed] |