Revised: July 19, 2013

Accepted: August 8, 2013

Published online: September 28, 2013

Processing time: 103 Days and 7.3 Hours

Hypertensive brain stem encephalopathy (HBE) is a rare, under diagnosed subtype of hypertensive encephalopathy (HE) which is usually reversible, but with a potentially fatal outcome if hypertension is not managed promptly. To the best of our knowledge, only one case of HE with brain stem hemorrhage has been reported. We report a case of HBE with pontine hemorrhage in a 36-year-old male patient. The patient developed severe arterial hypertension associated with initial computed tomography showing the left basilar part of pons hemorrhage, fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery showing hyperintense signals in the pons and bilateral periventricular, anterior part of bilateral centrum ovale. The characteristic clinical findings were walking difficulty, right leg weakness, and mild headache with nausea which corresponded to the lesions of MR imagings. The lesions improved gradually with improvements in hypertension, which suggested that edema could be the principal cause of the unusual hyperintensity on magnetic resonance images.

Core tip: Hypertensive brain stem encephalopathy (HBE) is a rare, underdiagnosed subtype of hypertensive encephalopathy. The disease is still not recognized by clinical doctors. The prompt diagnosis and treatment is crucial. Here, we report a case of HBE with pontine hemorrhage in a 36-year-old man. The case will help clinicians to further know about the disease.

- Citation: Zhou ZH, Qu F, Chen HS. Hypertensive brain stem encephalopathy with pontine hemorrhage: A case report. World J Neurol 2013; 3(3): 83-86

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6212/full/v3/i3/83.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5316/wjn.v3.i3.83

Hypertensive brain stem encephalopathy (HBE) is a rare, under diagnosed subtype of hypertensive encephalopathy (HE) which is usually reversible, but with a potentially fatal outcome when hypertension is not treated promptly[1]. The typical feature on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of HE are signals of increased intensity in the white matter of both occipital regions consistent with edema. The term “reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome” or “posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome” has been used to describe the characteristic neuroimaging features in HE[2,3]. Involvement of the brainstem in addition to the supratentorial lesions has been rarely reported, and is termed HBE. The typical imaging features of HBE are hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted MRI and swelling of the brainstem ,which may be misdiagnosed as brainstem infarction, pontine glioma, central pontine myelinolysis and infective encephalitis[1,4,5]. To the best of our knowledge only one case of HE with brain stem hemorrhage has been reported[6]. We report a case of HBE with pontine hemorrhage in a 36-year-old male patient.

A 36-year-old man with a history of poorly controlled hypertension presented with 2 d history of difficulty walking, right leg weakness, and mild headache with nausea. His blood pressure was 220/160 mmHg. The cranial nerve functions were intact, including visual function and an ophthalmologic examination. Clinical examination revealed Medical Research Council grade 4/5 strength in the right leg. Deep tendon reflexes were brisk with bilateral extensor plantar responses and positive Babinski sign.

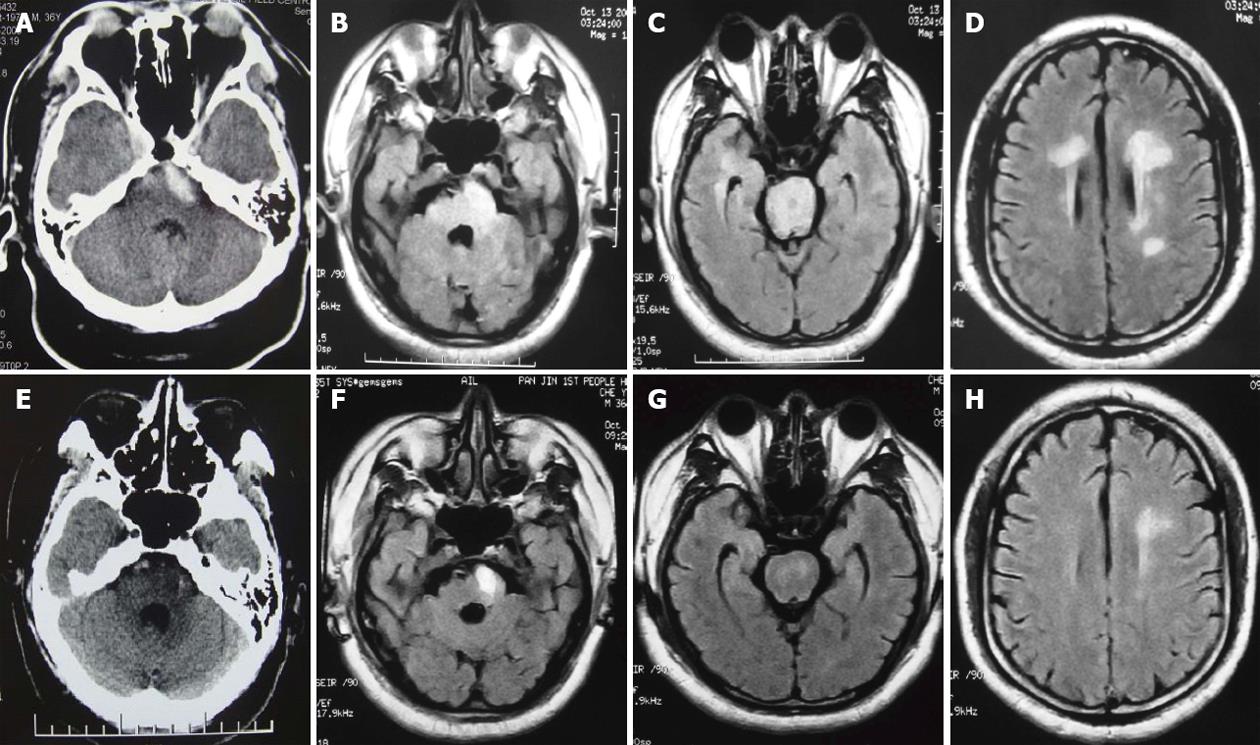

A laboratory evaluation on admission including renal function, hepatic function, serum electrolyte concentrations was unremarkable. Immunologic studies of the following were negative: antinuclear factor, antibodies to native DNA, antibodies to ribonucleoprotein, antibodies to smooth muscle, anti-Ro antibody (SS-A), anti-La antibody (SS-B), serum immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgA, or IgM, C3, C4, and serum immunocomplex. An antihuman immunodeficiency virus antibody was negtive. An electroencephalogram was normal. A CT showed high-density signal changes in the left basilar part of pons and mild swelling in the brainstem (Figure 1A). The T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (FLAIR) images showed high-intensity signal changes in the whole pon, bilateral periventricular, anterior part of bilateral centrum ovale (Figure 1B-D). The T1-weighted images showed moderate hyperintense signals and diffused-weighted images showed hyperintense signals in the left basilar part of pons where CT showed high-density signal changes. However, despite the presence of extensive neuroimaging brainstem lesions, there were no symptoms or signs of brainstem dysfunction.

Immediate treatment with pumped nitroprusside (3 μg/kg/min) led to gradual improvement in right leg weakness ,disappearance of the headache and rapid control of the BP, which decreased to 160/110 mmHg after 4 h. He was prescribed amlodipine and ramipril on the 3rd day. Ten days later, the systolic and diastolic pressures stabilized at 130-150 and 80-100 mmHg respectively. A cerebral CT performed two weeks later, showed low-density signal changes in the left basilar part of pons, suggesting absorption of the pontine hemorrhage (Figure 1E). The brainstem and supratentorial lesions except hemorrhage almost resolved as shown in FLAIR (Figure 1F-H) and T1-weighted images, after stabilization of his blood pressure.

At the time of discharge, 18 d later, the neurological examination revealed no abnormalities except for a right positive Babinski sign.

The BHE is characterized by very high blood pressure with marked clinicoradiologic dissociation. Patients typically have mild clinical and neurologic symptoms, prominent brainstem involvement and relatively mild supratentorial lesions with rapidly improved MR findings after controlling hypertension[7].

The clinical features of our case presented here were strongly suggestive of BHE, with severe hypertension, mild right leg weakness, headache, severe predominantly brainstem lesions and and subsequent improvement after a reduction in blood pressure.

In our patient, the diagnosis of BHE was difficult at first because of the co-existence of pontine hemorrhage and the whole brain edema. The differential diagnosis in these patients is: hypertensive pontine hemorrhage and hemorrhagic brain stem infarction. In both of these pathologies, patient would be in clinically grave situation and a poor prognosis based on the neuroimaging.

Brainstem infarction can be ruled out by the lack of major brainstem signs, rapid clinical recovery, predominant white matter involvement in T2-weighted and FLAIR images, and absence of signal changes in diffusion-weighted MRI except pontine hemorrhage.

Other differential diagnosis include central pontine myelinolysis (CPM), infectious brainstem encephalitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), neuro-Behcet disease, and tumor. CPM may produce a similar radiologic picture, but the absence of abnormal serum sodium levels, the clinical recovery, and resolution of the MRI lesions made the possibility of CPM quite unlikely. The rapidity of the clinical evolution should help differentiate their condition from tumors. The patient lacked skin and eye symptoms, aphthous stomatitis, and definitive brain stem symptoms, so we excluded neuro-Behcet disease. Infectious brainstem encephalitis or ADEM was unlikely because of mild clinical and neurologic symptoms, normal electroencephalogram, and rapid recovery without specific treatment although cerebrospinal fluid testing was not performed.

Intracerebral hemorrhage associated with HE is generally considered an atypical finding. Although the incidence of hemorrhage was 15.2%, brain stem hemorrhage is rare and only one case has been reported in the literature[6]. Intracerebral hemorrhage associated with HBE is much less frequent with 2 of 26 HBE patients reported in a reviews having a small thalamic hemorrhage simultaneously[8]. Our patient had HBE with pontine hemorrhage. No case of brain stem hemorrhage associated with HBE has been reported yet.

The proposed mechanism underlying HE involves the breakdown of autoregulation, resulting in dilatation of cerebral arterioles, the disruption of the blood-brain barrier, and the breakthrough accumulation causing vasogenic edema[9]. As the vertebrobasilar system and posterior cerebral arteries are sparsely innervated by sympathetic nerves[10], accounting for the susceptibility of the brain stem and other posterior brain regions to this breakdown of autoregulation.

The hemorrhage in our patient does not seem to be due to hypertensive rupture of small artery based on clinical presentation and rapid improvement of symptoms. It is thought to be due to a breakthrough of autoregulation by regional hyperperfusion and increased intracranial pressure due to the elevated blood pressure[11].

In conclusion, clinical recognition of HBE may be difficult. The features of a lack of correlation between the severity of the radiological abnormality and the clinical status, combined with the rapid resolution following antihypertensive treatment, should suggest the diagnosis. It is important for the radiologist to be familiar with the imaging abnormalities (especially with hemorrhage) of this life-threatening, but treatable condition. Rapid identification and appropriate diagnostics are essential, as prompt treatment usually results in reversal of symptoms; permanent neurologic injury or death can occur with treatment delay.

P- Reviewers Feltracco P, Ferreira CN, Waisberg J S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Yan JL

| 1. | Chang GY, Keane JR. Hypertensive brainstem encephalopathy: three cases presenting with severe brainstem edema. Neurology. 1999;53:652-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, Pessin MS, Lamy C, Mas JL, Caplan LR. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2250] [Cited by in RCA: 2153] [Article Influence: 74.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pavlakis SG, Frank Y, Chusid R. Hypertensive encephalopathy, reversible occipitoparietal encephalopathy, or reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy: three names for an old syndrome. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:277-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thambisetty M, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Hypertensive brainstem encephalopathy: clinical and radiographic features. J Neurol Sci. 2003;208:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kang SY, Choi JC, Kang JH. Two cases of hypertensive encephalopathy involving the brainstem. J Clin Neurol. 2007;3:50-52. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Aranas RM, Prabhakaran S, Lee VH. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome associated with hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:306-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shintani S, Hino T, Ishihara S, Mizutani S, Shiigai T. Reversible brainstem hypertensive encephalopathy (RBHE): Clinicoradiologic dissociation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:1047-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hefzy HM, Bartynski WS, Boardman JF, Lacomis D. Hemorrhage in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: imaging and clinical features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1371-1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Seze J, Mastain B, Stojkovic T, Ferriby D, Pruvo JP, Destée A, Vermersch P. Unusual MR findings of the brain stem in arterial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:391-394. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Edvinsson L, Owman C, Sjöberg NO. Autonomic nerves, mast cells, and amine receptors in human brain vessels. A histochemical and pharmacological study. Brain Res. 1976;115:377-393. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Schwartz RB. Hyperperfusion encephalopathies: hypertensive encephalopathy and related conditions. Neurologist. 2002;8:22-34. [PubMed] |