Published online Dec 31, 2024. doi: 10.5316/wjn.v10.i1.98672

Revised: November 28, 2024

Accepted: December 17, 2024

Published online: December 31, 2024

Processing time: 177 Days and 18.5 Hours

A stroke is a significant brain event that impinges on individual motor or cog

We focus on a 60-year-old female with subacute stroke presenting symptoms including tongue deviation to the right, speech difficulty, choking on water, and biting the oral mucosa. She did not exhibit abnormalities in limb movement or sensation except for numbness in the tongue. We use single-photon emission computed tomography to reveal reduced blood flow in the left parietal lobe and bilateral temporal lobes. This report presents an atypical case of dysarthria, who exhibits abnormal articulation along with abnormal sensation and numbness in the tongue, prompting further investigation into the association between lacunar stroke subtypes, altered blood perfusion in affected brain regions, and neu

Dysarthria-plus syndrome in lacunar stroke isn’t solely related to motor function but also affects sensory function such as oral numbness.

Core Tip: Lacunar stroke occurs due to blockage in specific small blood vessels resulting in hypoxia and damage in corresponding tissues, which is primarily classified into five types based on clinical symptoms. However, many other types remain to be thoroughly explored. We present a case where a subacute stroke manifested with symptoms such as involuntary deviation of the tongue to the right, speech difficulty, choking on water, and biting the oral mucosa, with the sole sensory manifestation of tongue numbness, which indicates a new type of lacunar stroke presenting in brain perfusion images.

- Citation: Tsai YH, Chen YH, Chao TC, Lin LF, Chang ST. New type of lacunar stroke presenting in brain perfusion images: A case report. World J Neurol 2024; 10(1): 98672

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6212/full/v10/i1/98672.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5316/wjn.v10.i1.98672

Stroke is a common cerebrovascular event impinging millions of people worldwide, potentially leading to partial paralysis, impairment of language function, memory loss, cognitive deficits, and vision loss, impacting daily life[1]. Stroke is primarily categorized into hemorrhagic and ischemic types, corresponding to different brain regions affected and exhibiting corresponding clinical symptoms[2]. Lacunar stroke occurs due to blockage in specific small blood vessels resulting in hypoxia and damage in corresponding tissues, which is primarily classified into five types based on clinical symptoms. The most common is the pure motor stroke/hemiparesis type[3,4]. However, many other types remain to be thoroughly explored.

Computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is the gold standard for diagnosing acute stroke[5,6], with CT used to identify hemorrhages or lesions such as aneurysms, while MR can visualize soft tissue[7]. When thrombosis arises in a big aneurysm, in the identical arterial territory, increasing arterial spin labeling signal and decreasing arterial spin labeling signal with reduced visibility on MR angiography can signify the threat of coming burst[8]. Additionally, adjunctive use of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) of the brain can visualize perfusional circulation in different cerebral regions, observing symmetry and color contrast to determine the extent of infarction in specific areas, providing a more precise assessment of clinical symptoms resulting from stroke[9]. We present a case where a subacute stroke manifested with symptoms such as involuntary deviation of the tongue to the right, speech difficulty, choking on water, and biting the oral mucosa, with the sole sensory manifestation of tongue numbness. Additional findings were observed on SPECT-CT.

A 60-year-old woman suddenly experienced numbness on the right side of her tongue, involuntary deviation of the tip of her tongue to the right, and difficulty speaking for three weeks.

The patient experienced occasional choking on water, chewing difficulties, slight limitations in activities of daily living, speech difficulty, and occasional biting of the oral mucosa, affecting precise pronunciation. She felt sluggishness and lack of agility in tongue control and speech.

The neurology department confirmed an acute stroke, excluding the possibility of occipital condyle syndrome and hypoglossal nerve lesions, with potential causes including vascular issues, tumors, cancer, and schwannoma three weeks ago.

The patient had no personal or family history of illness.

Manual muscle strength testing, which was normal with a score of 5, no local tenderness, normal limb sensation response, normal deep tendon reflexes, normal Hoffmann sign, and limb movements were normal.

No abnormalities were found on routine blood analysis.

MR images confirmed an acute stroke. MR findings of the brain revealed senile atrophy, ventricular dilatation, small vessel ischemic changes, some old lacunar infarcts observed in bilateral centrum semiovale, and acute lacunar infarct in the left corona radiata. SPECT found decreased absorption in the left parietal lobe (grade 1), mild decrease in absorption in bilateral temporal lobes (grade 0-1), and decreased absorption in the right frontal lobe in post-stroke cerebral blood flow.

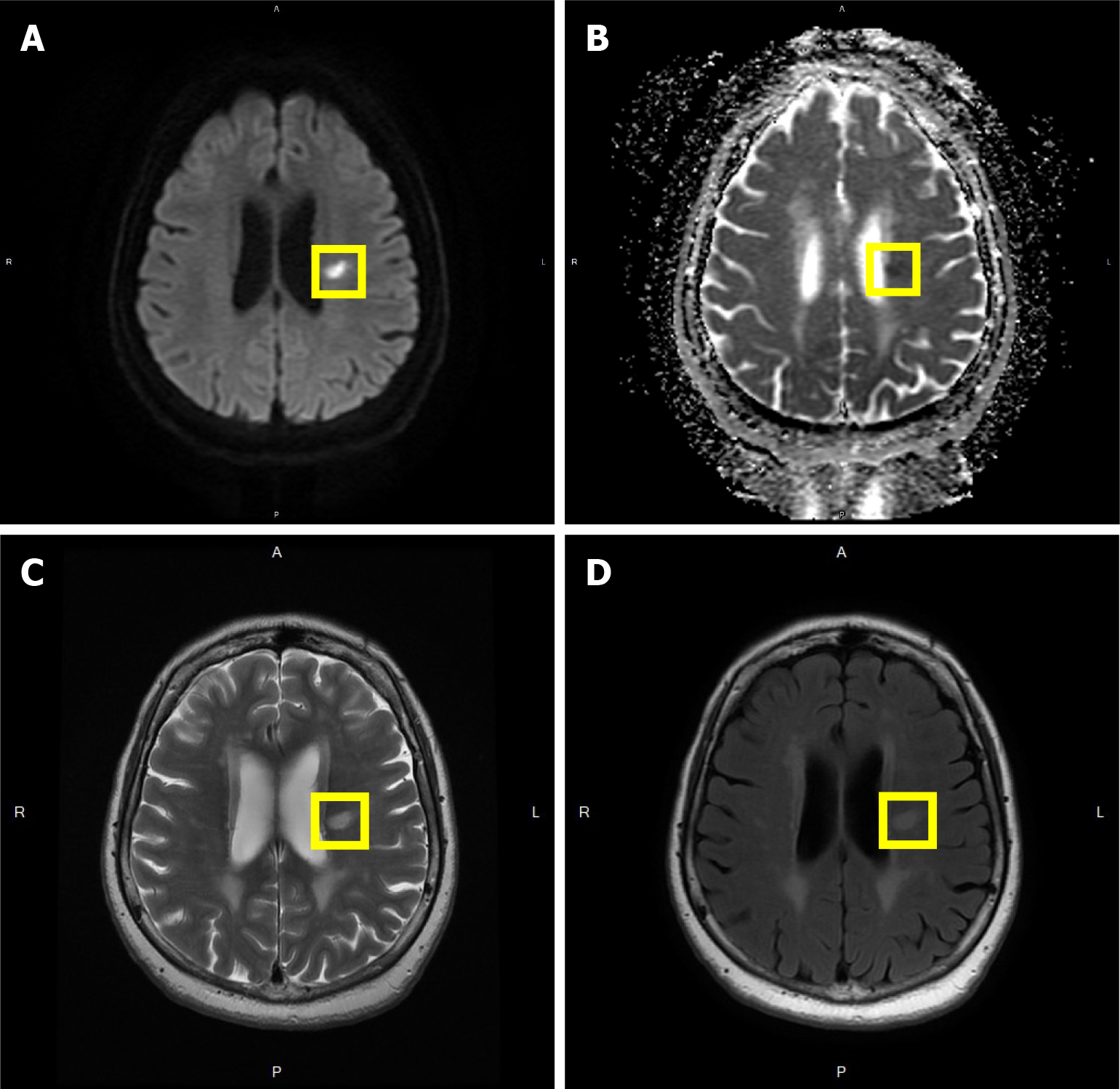

The patient sought medical attention at our hospital’s otorhinolaryngology department and was subsequently referred to the Department of Emergency due to a possible brain lesion, then admitted to the neurology department. At the beginning of her hospitalization, MR images confirmed an acute stroke, excluding the possibility of occipital condyle syndrome and hypoglossal nerve lesions, with potential causes including vascular issues, tumors, cancer, schwannoma, etc. Detailed MR findings of the brain revealed: (1) Senile atrophy with the widening of the peri cerebral cerebrospinal fluid space and corresponding ventricular dilatation. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery images showed bright signal changes, including subcortical and periventricular white matter, suggesting small vessel ischemic changes. Some old lacunar infarcts were observed in bilateral centrum semiovale; (2) Acue lacunar infarct in the left corona radiata; and (3) Cranial nerves II to VIII were delineated, without enlargement or enhancement. In summary, the patient had senile brain atrophy with small vessel ischemic changes and some old lacunar infarcts (Figure 1A-D). Five days later, she was discharged and returned to the neurology department for follow-up.

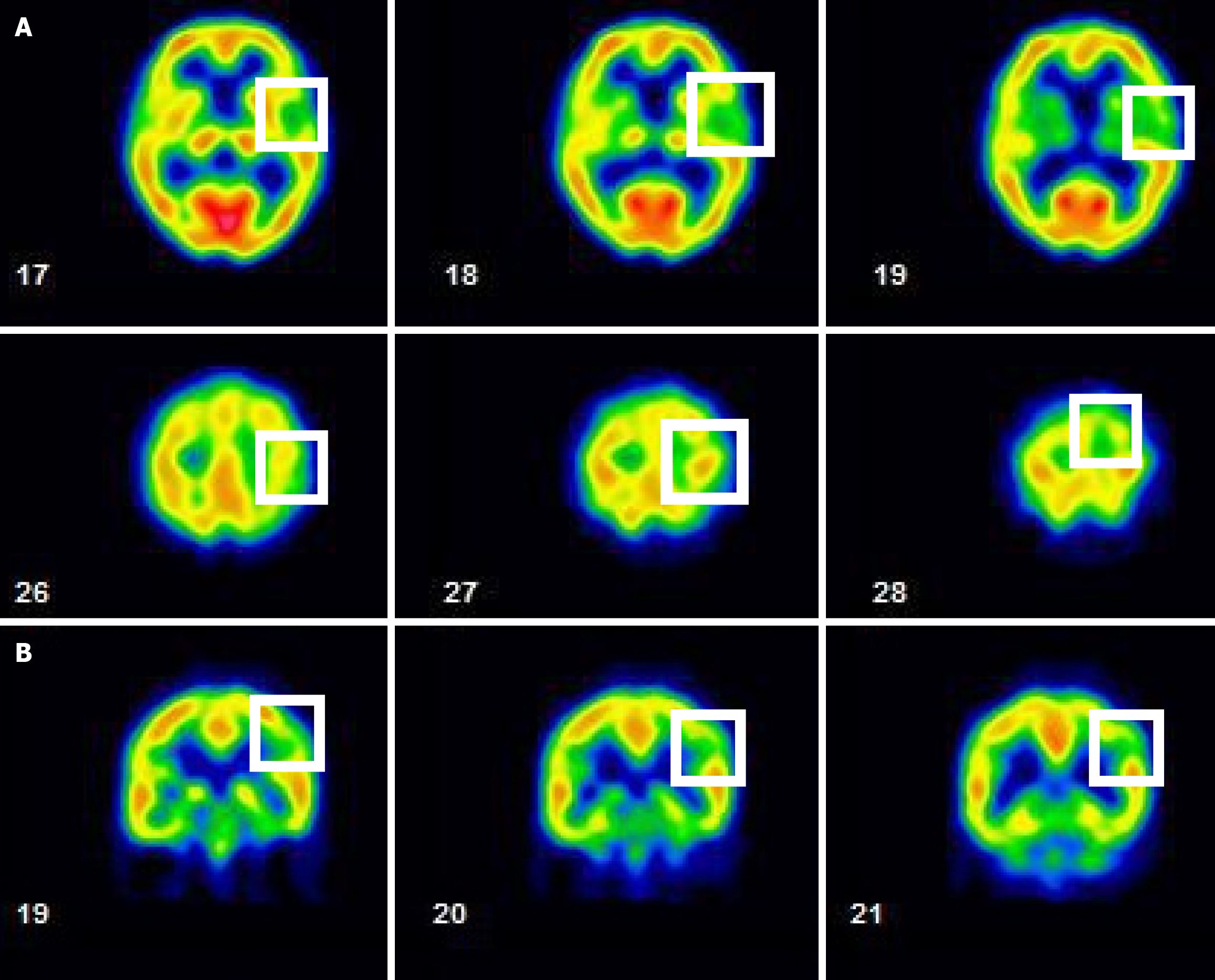

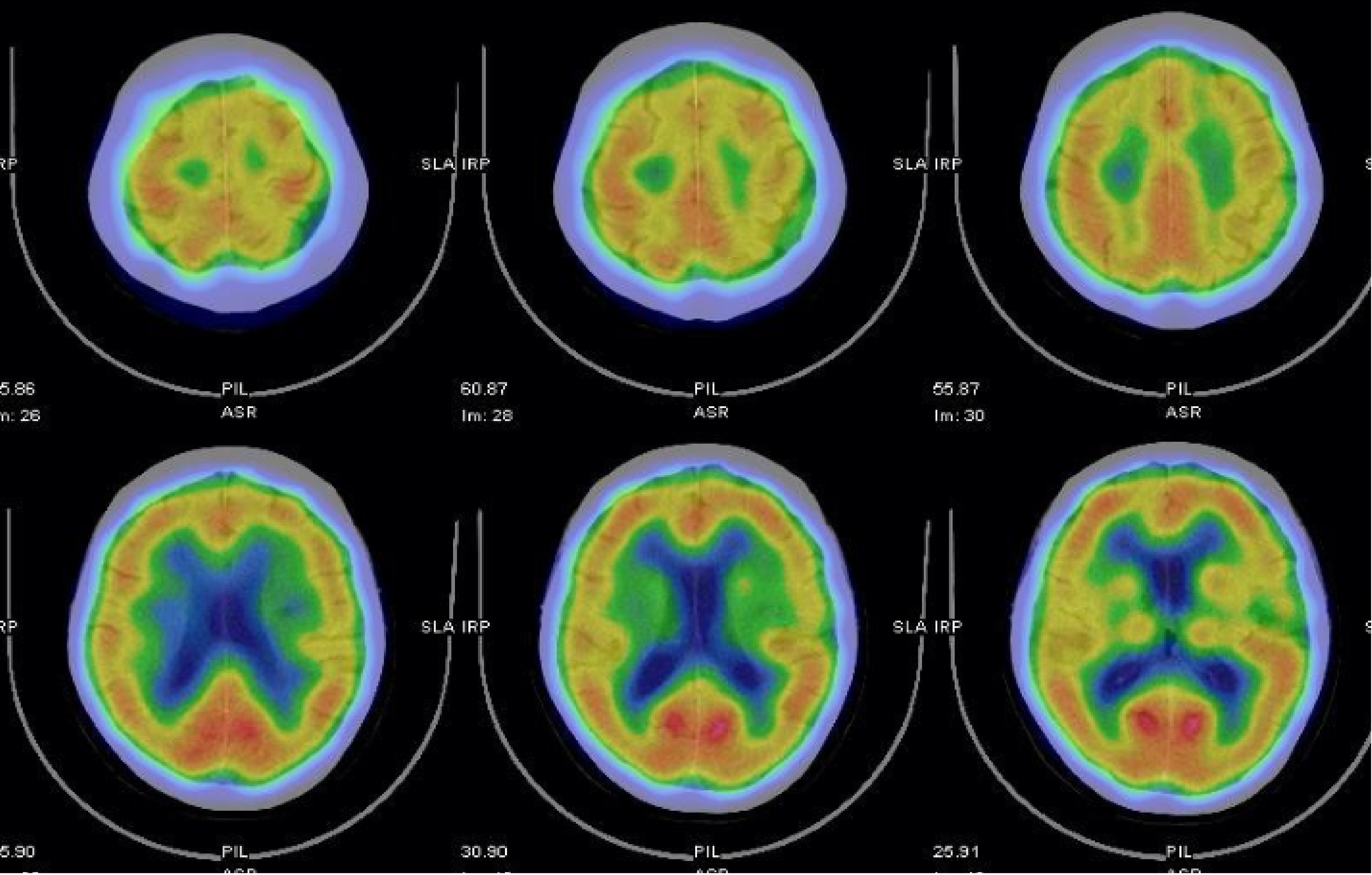

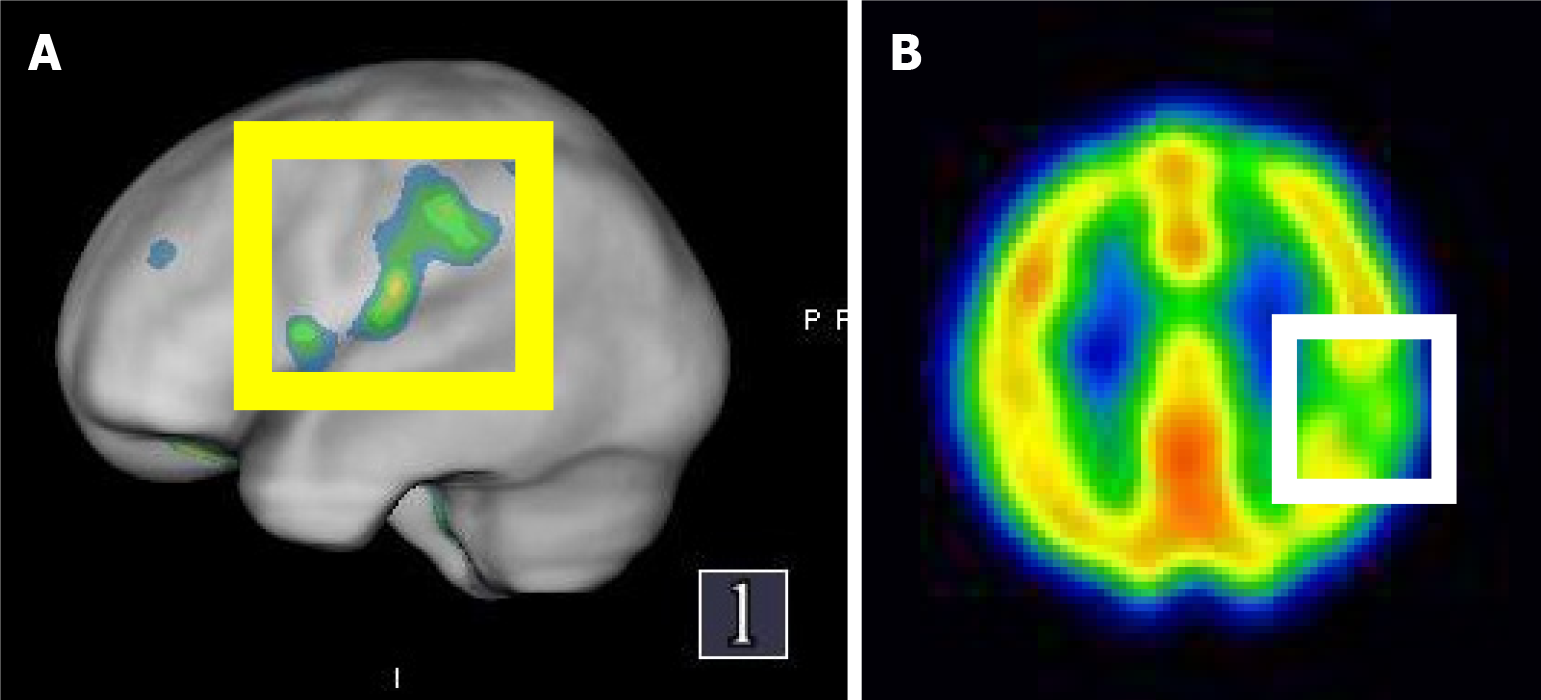

A cerebral perfusion scan of 99mTc-ethyl cysteine dimer-SPECT was arranged to observe post-stroke cerebral blood flow. The SPECT used in this case employs 99mTc-ethyl cysteine dimer as the radiopharmaceutical, which rapidly enters the brain and distributes based on local blood flow or metabolic activity, thus generating images. Although the resolution of SPECT is relatively low, it can effectively provide qualitative information on cerebral perfusion and reveal functional abnormalities. The resolution is influenced by factors such as the camera technology, the physical properties of the radiopharmaceutical, and the image reconstruction data processing algorithms. The SPECT images in this case were fused with “Q. brain” software, allowing for the quantification of cerebral blood flow in 3D images. These were compared with the average blood flow for the patient’s age group and corrected for left and right hemisphere blood flow, with standard deviation calculations to accurately depict the perfusion in various brain regions. The results showed decreased absorption in the left parietal lobe (grade 1), a mild decrease in absorption in bilateral temporal lobes (grade 0-1), and decreased absorption in the right frontal lobe (Figures 2, 3 and 4). The above results indicated mild cerebral hypoperfusion in the left parietal lobe related to a numb tongue and mild to moderate cerebral hypoperfusion in bilateral temporal lobes, which findings are highly related to neurodegenerative changes or aging. That is the reason why she had abnormal articulation and chewing dysfunction caused by dysarthria-plus syndrome, a new type of lacunar stroke.

The final diagnosis was cerebral infarction due to thrombosis with abnormal function of cerebral blood flow.

The patient was given conventional speech therapy, including oral exercise, tactile stimulation, and rhythm training.

The patient received regular speech therapy and was no follow-up after 4 months.

Our case showed difficulty speaking, choking on water, biting the oral mucosa while speaking, inability to pronounce accurately, and deviation of the tongue to the right side after a recent stroke. These symptoms were localized around the muscles of the mouth. However, she also had tongue numbness, which is a big difference from typical dysarthria. The brain perfusional scintigraphy showed decreased absorption in the left parietal lobe and mild decreases in absorption in bilateral temporal lobes. To our knowledge, this is the first case to show dysarthria accompanied by sensational abnormality, e.g., tongue numbness. We adopted a new type of lacunar syndrome, dysarthria-plus syndrome. Typical dysarthria commonly presents symptoms such as difficulty speaking, clumsy and weak hand movements, and possibly involuntary leg movements[10]. In this case, besides speech impairment, there was also tongue numbness, indicating involvement beyond oral motor functions. There were no abnormalities in the hands or legs, so we believe this case is not a typical dysarthria subtype but rather another atypical manifestation of lacunar stroke.

The clinical manifestations of lacunar stroke depend on the region of the brain affected, commonly seen in deep brain nuclei. Lacunar stroke can be clinically classified into the following five types based on symptoms: (1) Pure motor stroke/hemiplegic type (most common symptom 33%-50%); (2) Ataxic hemiparesis (10%-18%); (3) Pure sensory stroke (7%): Lesions in ventral posterolateral nucleus of contralateral thalamus; manifested as numbness or loss of sensation on one side of the body, with possible symptoms such as tingling, pain, or burning; (4) Sensorimotor stroke (second most common symptom, 20%); and (5) Mechanical speech disorder (articulation disorder), manifested as fluent speech, weakness of pronunciation muscles, such as tongue, larynx, and associated facial muscles, clumsiness of contralateral upper limbs, unchanged muscle strength, difficulty in fine motor tasks such as writing, tying shoelaces[3].

Furthermore, dysarthria in general and mechanical speech disorder due to lacunar stroke can be described in two aspects: (1) Regarding imaging, general dysarthria may not show significant lesions, whereas lacunar stroke typically presents with small, lacunar ischemic lesions; and (2) Clinically, dysarthria due to lacunar stroke is often accompanied by other neurological symptoms, such as mild hemiparesis or coordination difficulties, while the symptoms of general dysarthria can be more varied and are related to the underlying cause. Our case was similar to the fifth type, and additional involvement of sensory abnormalities. Therefore, we classify this case as another form of lacunar stroke. According to relevant literature, Foix-Chavany-Marie syndrome (FCMS) is a rare type of pseudobulbar palsy, manifested as dissociation of automatic and voluntary movements of the associated muscles of the face, tongue, pharynx, and chewing. Most cases of FCMS are caused by ischemia of the anterior operculum on the bilateral sides[4]. Interestingly, our case is similar to some clinical pictures of FCMS. The differences between the two are as follows: (1) Etiology and affected areas: FCMS involves the cortical motor areas, particularly those responsible for motor control of speech, whereas lacunar stroke typically affects deep structures such as the basal ganglia or brainstem; (2) Imaging: Imaging in FCMS typically reveals lesions in the cortical regions and their associated connections, while lacunar stroke presents as small, deep ischemic lesions; and (3) Clinical symptoms: The language impairment in FCMS is primarily characterized by motor speech difficulties (inability to produce speech), while lacunar stroke is associated with dysarthria (unclear speech or irregular speech rate) and may present with additional neurological symptoms.

We used cerebral perfusional SPECT for cerebral blood flow evaluation to provide more accurate localization of blood flow in different brain regions and discuss the relationship between clinical symptoms and brain damage. The advantages, principles, and timing of SPECT use have been discussed[9]. The clinical practice of this perfusion imaging should be encouraged for the decision-making process in the acute phase of stroke[11]. Brain SPECT acts as a wonderful tool for the evaluation of disease progression and an index for modification of therapy in varying disorders[12]. Although SPECT is not a primary diagnostic tool for dysarthria, it can serve as an adjunctive examination in certain cases to help assess brain function related to speech control. Pure dysarthria is often caused by lacunar stroke resulting in reduced blood flow perfusion in the cortical area, affecting the flow of blood in cortical and subcortical regions, especially in the precentral gyrus and central anterior frontal lobe areas, having a significant impact on articulation[13]. However, in our case’s SPECT images, there was a mild reduction in blood flow perfusion in the frontal lobe, but interestingly, more pronounced blood flow obstruction in the parietal and temporal lobes, which may be related to the presence of sensory abnormalities such as tongue numbness in the clinical symptoms.

Regarding the pathophysiology of dysarthria, most isolated dysarthria cases showed lesions observed from brain MR images occur in the deep brain structures, for instance, corona radiata and internal capsule, affecting the control of tongue movement[14]. However, relevant lesions were not observed in the MR images of our case. To understand the patient’s speech characteristics, including pronunciation, intonation, and consonant production, and their relationship with the location of brain lesions, it was pointed out that the articulation disorder of dysarthria is mostly caused by left-sided brain damage. Regardless of the location of the lesion, the severity of articulation disorders caused by left-sided damage is more pronounced and lesions occur along the cortical brainstem fiber pathway, rather than between subcortical and brainstem damage[15]. The condition of our case was consistent with theirs. Due to the varying degrees of impact that specific brain regions have on sensory and motor functions, the addition of SPECT as an adjunctive diagnostic tool, alongside the initial first-line imaging modalities (CT and MRI), can provide a more precise link between clinical symptoms and lesions, offering a more targeted therapeutic strategy.

Regarding differential diagnosis of dysarthria, some cases may present with speech impairments and isolated supranuclear facial paralysis without motor dysfunction in the limbs. Therefore, when making a diagnosis of dysarthria, the possibility of facial paralysis syndrome should be included, since facial paralysis is usually mild and temporary, it may be easily overlooked[16]. Therefore, if dysarthria is present, motor-evoked potential stimulation can be used to observe response capability and changes in oral motor function[17]. It may be necessary to consider whether the con

We suggest that dysarthria in lacunar stroke is not solely related to motor function but also affects sensory function. Aside from common sites like the internal capsule, corona radiata, and basal ganglia, infarctions in the parietal and temporal lobes may also result in oral sensory abnormalities and numbness. Further research is needed to elucidate the precise pathophysiology and neural pathways involved.

The authors thank the patient for giving consent to publish the case details. In addition, the author thanks Yu-Cheng Pai for the resource collection.

| 1. | Ramos-Lima MJM, Brasileiro IC, Lima TL, Braga-Neto P. Quality of life after stroke: impact of clinical and sociodemographic factors. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sallés L, Gironès X, Lafuente JV. [The motor organization of cerebral cortex and the role of the mirror neuron system. Clinical impact for rehabilitation]. Med Clin (Barc). 2015;144:30-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Toni D, Del Duca R, Fiorelli M, Sacchetti ML, Bastianello S, Giubilei F, Martinazzo C, Argentino C. Pure motor hemiparesis and sensorimotor stroke. Accuracy of very early clinical diagnosis of lacunar strokes. Stroke. 1994;25:92-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yoshii F, Sugiyama H, Kodama K, Irino T. Foix-Chavany-Marie Syndrome due to Unilateral Anterior Opercular Damage with Contralateral Infarction of Corona Radiata. Case Rep Neurol. 2019;11:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tesson A, Kranz P, Zomorodi A, Morgenlander J. Something Got Your Tongue? A Unique Cause of Hypoglossal Nerve Palsy. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2022;2022:2884145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yi K, Inoue M, Irie K, Mizoguchi T, Miwa K, Toyoda K, Koga M. Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Cortical Embolism Stroke with Magnetic Resonance Perfusion Imaging: A Report of Two Cases. Case Rep Neurol. 2019;11:222-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vivancos J, Gilo F, Frutos R, Maestre J, García-Pastor A, Quintana F, Roda JM, Ximénez-Carrillo A; por el Comité ad hoc del Grupo de Estudio de Enfermedades Cerebrovasculares de la SEN:, Díez Tejedor E, Fuentes B, Alonso de Leciñana M, Alvarez-Sabin J, Arenillas J, Calleja S, Casado I, Castellanos M, Castillo J, Dávalos A, Díaz-Otero F, Egido JA, Fernández JC, Freijo M, Gállego J, Gil-Núñez A, Irimia P, Lago A, Masjuan J, Martí-Fábregas J, Martínez-Sánchez P, Martínez-Vila E, Molina C, Morales A, Nombela F, Purroy F, Ribó M, Rodríguez-Yañez M, Roquer J, Rubio F, Segura T, Serena J, Simal P, Tejada J. Clinical management guidelines for subarachnoid haemorrhage. Diagnosis and treatment. Neurologia. 2014;29:353-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ueno T, Sasaki T, Iwamura M, Kon T, Nunomura JI, Midorikawa H, Tomiyama M. Arterial Spin Labeling Imaging of a Giant Aneurysm Leading to Subarachnoid Hemorrhage following Cerebral Infarction. Case Rep Neurol. 2018;10:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oku N, Kashiwagi T, Hatazawa J. Nuclear neuroimaging in acute and subacute ischemic stroke. Ann Nucl Med. 2010;24:629-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Loeb C. The lacunar syndromes. Eur Neurol. 1989;29 Suppl 2:2-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nguyen TH, Pham BN, Phan HT, Nguyen TQ, Phan BV. Perfusion-Based Decision-Making for Mechanical Thrombectomy in a Transient Ischemic Attack Patient with Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion. Case Rep Neurol. 2020;12:41-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chiang CC, Wu YC, Lan CH, Wang KC, Tang HC, Chang ST. Exploring CNS Involvement in Pain Insensitivity in Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy Type 4: Insights from Tc-99m ECD SPECT Imaging. Tomography. 2023;9:2261-2269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Okuda B, Kawabata K, Tachibana H, Sugita M. Cerebral blood flow in pure dysarthria: role of frontal cortical hypoperfusion. Stroke. 1999;30:109-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Urban PP, Wicht S, Hopf HC, Fleischer S, Nickel O. Isolated dysarthria due to extracerebellar lacunar stroke: a central monoparesis of the tongue. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:495-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Urban PP, Rolke R, Wicht S, Keilmann A, Stoeter P, Hopf HC, Dieterich M. Left-hemispheric dominance for articulation: a prospective study on acute ischaemic dysarthria at different localizations. Brain. 2006;129:767-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim JS. Pure dysarthria, isolated facial paresis, or dysarthria-facial paresis syndrome. Stroke. 1994;25:1994-1998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khedr EM, Abdel-Fadeil MR, El-Khilli F, Ibrahim MQ. Impaired corticolingual pathways in patients with or without dysarthria after acute monohemispheric stroke. Neurophysiol Clin. 2005;35:73-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |