Peer-review started: March 19, 2019

First decision: September 17, 2019

Revised: October 26, 2019

Accepted: December 6, 2019

Article in press: December 6, 2019

Published online: December 20, 2019

Processing time: 280 Days and 14.2 Hours

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare neoplastic disease in dendritic cells. LCH is classified as either a single-system (SS) or multisystem (MS) disease. There is not a standard first-line treatment for LCH in adults. We analyzed the efficacy and safety of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) by searching PubMed/MEDLINE for case reports previously published. The clinical response (nonactive disease or active disease that regressed) was 94% in SS and 53% in MS. IMiDs should only be considered for adults with cutaneous SS involvement; in MS, they should be used only for patients not eligible for more aggressive treatments.

Core tip: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare neoplastic disease derived from dendritic cells that is seen in children as well as in adults. There is not a standard first-line treatment in adults; no prospective trials have been undertaken on this population, and chemotherapy schedules are often reported from pediatric experiences with suboptimal efficacy and a higher toxicity in adults than in children. Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), as less toxic therapeutic options, have been considered for treating LCH. We analyzed the efficacy and safety of IMiDs in adults with LCH from previously published research.

- Citation: Mauro E, Stefani PM, Gherlinzoni F. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis and immunomodulatory drugs: Review and analysis of thirty-four case reports. World J Hematol 2019; 8(1): 1-9

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6204/full/v8/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5315/wjh.v8.i1.1

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare neoplastic disease derived from dendritic cells that is seen in children as well as in adults[1]. The LCH incidence is estimated to be 1-2 cases per million in adults[2,3]. The diagnosis of LCH is based on histologic and immunophenotypic evaluations of lesions: In particular, evidence of Langerhans cell infiltrates with a positivity for CD1a and/or CD207 (Langerin) as seen on an optical microscope or the presence of Birbeck granules as seen on an electronic microscope. Multiple organs may be involved in generating a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations[4,5], from a skin rash to an explosive disseminated disease. In particular, the disease may affect organs or organ systems, especially the bone, skin, pituitary gland, lymph nodes, liver, spleen, gut, central nervous system (CNS), bone marrow, and lungs, with focal or multifocal infiltrates[1,6], that results in different outcomes. The expert panel on behalf of the Euro-Histio-Net classified the disease as either single system LCH (SS-LCH) or multisystem LCH (MS-LCH) (two or more organs/system involved) with or without the involvement of high-risk organs such as bone marrow, spleen, liver or CNS[6]. Recently, mutations in the BRAF gene have been reported in approximately 50% of cases, representing a breakthrough in understanding the pathogenesis of LCH[7-9]. In particular, BRAF mutations induce constitutive activation of downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinases, offering new therapeutic targets for the MAPK pathway[9]. Based on multifocal or focal LCH and on the involvement at special sites, the treatment changes[6]. However, there is not a standard for first-line treatment for adults with LCH; no prospective trials have been undertaken on this population, and the therapy schedules are often reported from pediatric experiences[1,6,10]. Therefore, the treatment depends on the extent and severity of the disease at onset. In particular, the pediatric treatment schedule for vinblastine in combination with a prednisone has been used in adults but has a suboptimal efficacy and higher toxicity in adults than in children[11]. Other therapeutic approaches for MS-LCH adults include monotherapy with cladribine, cytarabine, etoposide or polychemotherapy regimens[11-14]. According to the expert panel of Euro-Histio-Net, recommendations for first-line therapy are summarized in Table 1[6]. Among the therapeutic options with activity against LCH, immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) have been taken into account. In LCH, a variety of cytokines, IL-1, IL-10, interferon gamma, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), are expressed at high levels and play key roles in the pathogenesis of disease[15]. TNF-α is considered the major promoter for Langerhans cell proliferation and production from hematopoietic stem cells, and its expression is modulated by IMiDs[16]. Here, we analyzed the efficacy and safety of IMiDs in LCH.

| Disease category | Treatment |

| Unifocal LCH | |

| Skin | Local therapy (e.g., topical mustard nitrogen 20% in children) |

| Phototherapy: PUVA, narrow band ultraviolet B | |

| Bone | Intralesional steroid injection (40-160 mg methylprednisolone) |

| Radiotherapy (in case of neurological deficit, soft tissue involvement) | |

| Multifocal SS-LCH without “organ risk” | |

| SS-LCH (bone lesions) | Zoledronic acid |

| SS-LCH (skin) | Methotrexate 20 mg per week p.o/i.v. |

| Azathioprine 2 mg/kg/d p.o. | |

| Thalidomide 100 mg/die p.o. (skin or soft tissue multifocal SS-LCH if symptomatic) | |

| Symptomatic MS-LCH without “risk organs” | Cytarabine 100 mg/m2 d1-5 q4w i.v. |

| Etoposide 100 mg/m2 d1-5 q4w i.v. | |

| Vinblastin/Prednisone (“pediatric like schedule”) | |

| MS-LCH with “risk organs” | 2-CDA 6 mg/m2 d1-5 q4w s.c./i.v. |

| PLCH asymptomatic | Quit smoking |

| Careful observation | |

| PLCH symptomatic | Sistemic steroids |

| Chemotherapy in case of progressive disease | |

| In case of severe respiratory failure or major pulmonary failure consider lung transplantation | |

To summarize the current experience of IMiDs as the treatment for LCH, we conducted a PubMed/MEDLINE search for case reports and case series from 1987 until 2018. The search items used were LCH, IMiDs, thalidomide, and lenalidomide; the limits set were case reports, human, and English, French and German languages. A total of 53 articles were found. Review articles, pediatric cases and in vitro analyses were excluded. A total of 29 articles about case reports or case series were found[10,17-44]. Six patients treated with thalidomide were included in the study for a toxicity and efficacy analysis[45]. According to the Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society[46] and recommendations from the Euro-Histio-Net[6], in all collected cases, the histopathological diagnosis was made with positivity of CD1a and/or Langherin (CD207) or the presence of Birbeck granules on electronic microscopy. All patients were treated with IMiDs. Moreover, evaluating every single case, we stratified the disease as SS-LCH or MS-LCH. Briefly: SS-LCH is defined as having one organ or system involved (in particular, bone with single or multiple lesions, skin, lymph node, hypothalamic-pituitary/CNS, lungs or other systems), and MS-LCH is defined as having two or more organs or systems involved[6]. To assess the disease state after treatment, we applied the HS criteria to every case description[47]. Briefly, if the authors reported that all signs and symptoms were resolved, we considered the described patients as having a nonactive disease (NAD); otherwise, the patients were classified as having active disease (AD). AD was further subdivided into regressive [active disease regressive (ADR); improvement in the symptoms or signs, with no new lesions], stable [Active disease stable (ADS); persistence of symptoms or signs, with no new lesions], or progressive disease (PD) (progression and/or appearance of new lesions).

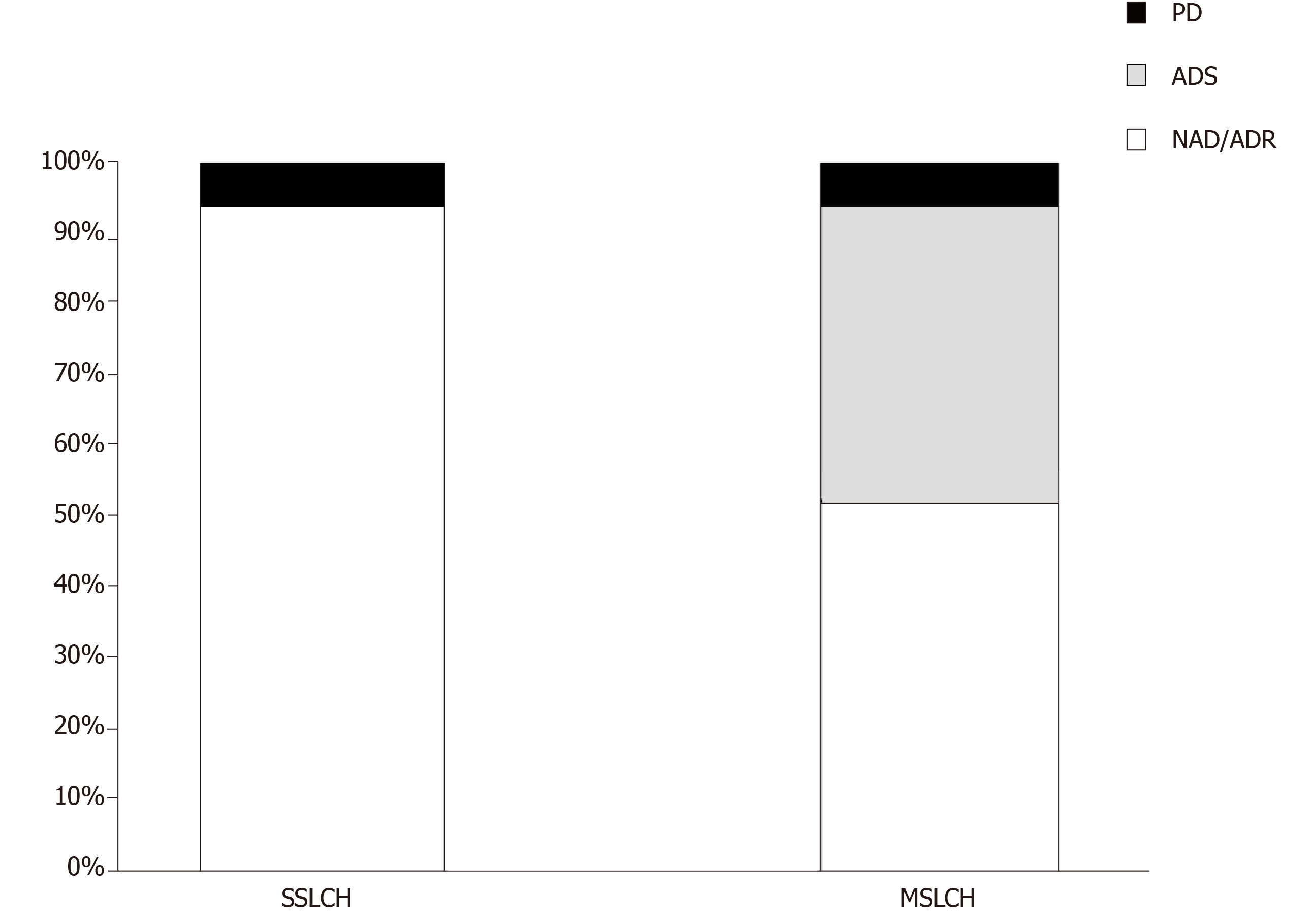

A total of 34 patients (21 female and 13 male) were included in this study, including 17 SS-LCH and 17 MS-LCH patients. Detailed information of each patient is displayed in Table 2. The mean age at diagnosis was 45.3 years (range 20-73). The skin or mucocutaneous involvement was reported in 32 patients (94%), and these patients were considered as having only a single organ represented in the SS-LCH group. In addition, the following involved areas were reported: the genital/perineal zone in 22 patients, trunk in 10 patients, groins in 9 patients, axillary involvement in 7 patients, scalp in 5 patients, buccal/mucosal involvement in 5 patients, face in 4 patients, nails in 3 patients, neck in 2 patients, external auditory meatus in 1 patients, retroauricular zone 1 patients, and feet 1 patients. The other organs involved are reported in Table 3. Thalidomide was used in 32 patients, and lenalidomide was used in 2 patients. In 14 patients [7 SS-LCH (20.5%) and 7 MS-LCH (20.5%)], thalidomide was the first-line therapy, while in 20 patients (58.8%) IMiDs were the therapy that followed treatment with steroids, radiotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy. The details of treatment types are summarized in Table 4. The mean thalidomide dosage was 155 mg/d (range 50-500 mg), and the mean lenaldomide dosage was 25 mg/d in case study of Szturz et al[41] and 10 mg/d in the case study by El-Safadi et al[24]. The mean duration of therapy with IMiDs was 10.7 mo. Regarding adverse events, the authors reported fatigue/somnolence in 9 patients (22.5%), neuropathy in 6 patients (15%), constipation in 1 patient (2.5%), thrombosis in 1 patient(2.5%), skin rash in 1 patient(2.5%), and neutropenia in 1 patient (2.5%). Regarding the outcomes, considering NAD and ADR, the overall response rate was 73.5%; ADS was reported in 20.5% of patients, and PD was reported in 6% of patients. In the SS-LCH group, 16 patients (94%) achieved NAD/ADR and one patient (6%) achieved PD; in the MS-LCH group, 9 patients (53%) achieved NAD/ADR, 7 patients (41%) achieved a ADS and one patient had PD (Figure 1). After starting therapy, the follow-up was evaluable in 30 patients with any response (NAD/ADR/ADS/PD) at a mean of 11.6 mo (range 3-60). During follow-up, 7 patients (23.3%) (2 SS-LCH and 5 MS-LCH) were referred for other cytotoxic regimens because of relapse or suboptimal disease control.

| Ref. | Publication year | Age | Sex | SS-LCH (1) MS-LCH (2) | Previous therapies | IMiDS dose1 | Duration (mo) | Out come |

| Gnassia et al[27] | 1987 | 32 | F | 1 | No | 50 | 60 | NAD |

| Viraben et al[43] | 1988 | 48 | M | 1 | NA | 300 | 1 | NAD |

| Bensaid et al[19] | 1992 | 29 | F | 2 | No | 100 | 3 | ADR |

| Misery et al[33] | 1993 | 67 | M | 1 | No | 200 | 3 | NAD |

| Thomas et al[42] | 1993 | 24 | F | 2 | No | 50 | 3 | ADS |

| Thomas et al[42] | 1993 | 59 | F | 2 | Prednisone | 50 | 18 | ADS |

| Dallafior et al[23] | 1995 | 65 | F | 1 | Cladribin | 200-100 | 10 | NAD |

| Meunier et al[32] | 1995 | 66 | M | 1 | No | 100 | 2 | NAD |

| Bouyssou-Gauthier et al[21] | 1996 | 68 | M | 2 | Cyclophosph-mide/steroids | NA | NA | ADS |

| Gerlach et al[26] | 1998 | 73 | F | 2 | Etoposide/topi-cal mustard | 200 | 12 | ADR |

| Lair et al[29] | 1998 | 33 | F | 2 | RT/surgery | 100 | 28 | ADS |

| Claudon et al[22] | 2002 | 44 | F | 2 | Metotrexate/ste-roids | 100 | 4 | ADR |

| Kolde et al[28] | 2002 | 23 | M | 2 | No | 500 | 3 | ADS |

| Kolde et al[28] | 2002 | 61 | F | 2 | Prednisone | 500 | 16 | ADS |

| Mortazavi et al[35] | 2002 | 29 | M | 2 | No | 100 | 2 | ADS |

| Santillan et al[38] | 2003 | 33 | F | 1 | RT/surgery | 100 | 12 | NAD |

| Padula et al[36] | 2004 | 31 | F | 1 | RT/surgery | NA | NA | NAD |

| Sander et al[37] | 2004 | 38 | M | 1 | Cladribin | 200 | 6 | NAD |

| Mauro et al[31] | 2005 | 73 | F | 2 | CVP | 100 | 7 | ADR |

| Alioua et al[17] | 2006 | 43 | F | 2 | No | 100 | 12 | ADR |

| Moravvej et al[34] | 2006 | 27 | M | 1 | PUVA | 100 | 3 | ADR |

| Wollina et al[44] | 2006 | 38 | M | 2 | Cladribin | 200 | 9 | NAD |

| Broekaert et al[20] | 2007 | 57 | F | 2 | No | 50 | 24 | ADR |

| McClain et al[10] | 2007 | 45 | F | 1 | Vinorelbine/ prednisone | 100 | 22 | NR/PD |

| McClain et al[10] | 2007 | 31 | F | 2 | Vinorelbine/ prednisone/RT | 100 | 0,5 | NR/PD |

| McClain et al[10] | 2007 | 21 | F | 2 | Vinorelbine/ prednisone/RT | 100 | 5 | NAD |

| McClain et al[10] | 2007 | 46 | F | 2 | Vinorelbine/ prednisone/RT | 100 | 12 | NAD |

| Li et al[30] | 2010 | 27 | M | 1 | No | 150 | 5 | NAD |

| Fernandes et al[25] | 2011 | 60 | F | 1 | No | 100 | 4 | NAD |

| Shahidi-Dadras et al[39] | 2011 | 20 | M | 1 | Topical steroid | 200 | 6 | NAD |

| Szturz et al[41] | 2012 | 35 | M | 2 | Cladribin/ Cyclophospha-mide methilpredniso-lone/RT/CHO-EP/BEAM | Lena 25 | 9 | ADR |

| El-safadi et al[24] | 2012 | 59 | F | 1 | Surgery/RT/ MTX | Lena 10 | 19 | NAD |

| Subramaniyan et al[40] | 2015 | 71 | M | 1 | No | 200 | 10 | NAD |

| Ruiz Beguerie et al[18] | 2017 | 56 | F | 1 | No | 150 | 12 | NAD |

| Clinical features | All patients (%) |

| Female | 21 (62) |

| Age at diagnosis mean (range) | 45.3 (20-73) |

| Muco-cutaneous involvement | 32 (94) |

| Multiorgan involvement | 17 (50) |

| Lung involvement | 3 (9) |

| CNS/pituitary involvement | 8 (23.5) |

| Bone involvement | 6 (18) |

| Lymph nodes involvement | 3 (9) |

| Splenomegaly/hepatomegaly | 2 (6) |

| Others sites involved (bone marrow, parotid gland) | 2 (6) |

| Treatment before IMiDs | n (%) |

| None | 14 (41) |

| Radiotherapy | 8 (23.5) |

| Steroids | 8 (23.5) |

| Vinorelbine | 4 (12) |

| Surgery | 4 (12) |

| Cladribin | 4 (12) |

| Metotrexate | 2 (6%) |

| Polichemotherapy regimens | 2 (6) |

| Cyclophosphamide (single agent) | 2 (6) |

| Topical drugs | 2 (6) |

| Etoposide | 1 (3) |

| PUVA | 1 (3) |

Because of the rarity of LCH, there are no standard therapies for adults, and no prospective trials have been undertaken on this setting population. According to the standard pediatric treatment, the vinblastine/prednisone treatment experience has been employed in adults; however, suboptimal efficacy and near universal toxicity have been reported[11]. More recently, in a retrospective study, 35 adults (28 patients with MS-LCH) were treated with vinblastine and steroids as a first-line therapy, achieving an overall response rate of 71%[48]. In this study, neutropenia was reported in 17% of patients, peripheral sensitive neuropathy (grade 2) in 26% of patients, and peripheral motor neuropathy (grade 2) in 3% of patients[48]. As an alternative choice to vinblastine, other drugs, such as cladribine and cytosine arabinoside (ARA-c), have been considered in adults[1,11]. In particular, Saven et al[14] conducted phase II trials with cladribine; in total, 13 patients were enrolled with an overall response rate of 75% with not only skin involvement but also soft tissues, lymph nodes, bones and pulmonary sites. The principal acute toxicity was hematologic with seven patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 neutropenia. On other hand, Cantu et al[11] reported a retrospective study in which the poor response rate of ARA-c (21%) and the number of grade 3-4 toxic events (20%) were lowest of the three regimens shown in the study (vinblastine, cladribin and ARA-c) in patients with bone involvement. Retrospective analyses of the MACOP-B regimen (methorexate, doxorubicin, cyclosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin) have shown high efficacy[13] in adults with LCH. However, this intensive treatment should be reserved for very severe cases. The BRAF-V600E mutation gene discovery paved the way for targeted therapies such as BRAF or MEK inhibitors in patients with LCH[49]. In particular, vemurafenib is the first selective BRAF inhibitor approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for malignant melanomas where BRAF mutations are expressed. However, in melanoma trials, vemurafenib was associated with considerable toxicity, including secondary squamous cell carcinoma, in over 30% of patients; moreover, the optimal dosage and duration of this treatment require further investigation[50]. A variety of cytokines are expressed in LCH lesions. In particular, high levels of IL-1, IL-10 and TNF-α have been reported[15]. IMiDs such as thalidomide and lenalidomide (an analogue of thalidomide) are cytokine modulators, especially for the inhibition of TNF-α; therefore, these drugs have been considered feasible candidates for the treatment of LCH. However, the evaluation of the efficacy and safety of IMiDs in LCH are limited mostly to case reports. To our knowledge, the study of McClain et al[10] is the only phase II trial using thalidomide for LCH. In this study, the authors enrolled 16 patients: 12 pediatric patients (ages from birth to 3 years) and 4 adult patients (ages from 34 years to 46 years). Moreover, in 2004, Sander and coworkers reported a cutaneous LCH case successfully treated with thalidomide and reported ten cases published in the literature with similar clinical features[37]. In 2013, European panel of experts established recommendations about the diagnosis and therapy[6]. Grades of treatment recommendations were based on non-analytic studies (for example, case reports, case series, small retrospective studies, and expert opinions). After reviewing the literature[10,37], thalidomide was advised for LCH with mild symptoms in skin or soft tissue multifocal single system without risk organs involved. We performed a literature search for case reports on LCH treated with IMiDs and found 34 cases from 1987 to 2018. In our study, 94% of patients with SS-LCH achieved the best response (NAD/ADR) (Figure 1). In total, 50% of patients reported were MS-LCH (Table 3); in this analysis, the response rate for patients with NAD/ADR was 53%, and ADS was found in 41% of the patients. After somnolence, neuropathy is the most reported adverse event (16% of patients). In addition to the previously reported studies and recommendations from panel experts, we confirm in a larger setting of patients that IMiDs should be considered for treating adult patients with only mucocutaneous involvement; however, in the MS-LCH group, as expected, the IMiDs show a lower response rate. Therefore, other therapeutic approaches such as ARA-c, cladribin or vinblastine are recommended. In conclusion, IMiDs are a validated alternative to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents in most patients with SS-LCH; on other hand, considering the response rate in our study (53%) in patients with MS-LCH, IMiDs could be an evaluable choice for the treatment only in a limited number of patients based on age, compliance, performance status, expected toxicities, previous treatments, neuropathy or other comorbidities that make the patients not eligible for more aggressive treatments. Our study has several limitations. A publication bias toward more interesting and/or severe cases and successfully treated cases may lead to an over- or underestimation of the efficacy and safety of IMiDs in LCH. Prospective research for optimal treatment strategies for LCH should be warranted, albeit difficult to conduct for epidemiological reasons.

Different therapeutic strategies have been proposed for treatment of LCH in adults. The efficacy and safety of IMiDs have been reported in the treatment of multifocal SS-LCH (in particular skin or soft tissue if symptomatic). However, IMiDs could play a key role also in MS-LCH only in a limited setting of patients not eligible for more aggressive schedules.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Hematology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Diamantidis MD S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:26-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goyal G, Shah MV, Hook CC, Wolanskyj AP, Call TG, Rech KL, Go RS. Adult disseminated Langerhans cell histiocytosis: incidence, racial disparities and long-term outcomes. Br J Haematol. 2018;182:579-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baumgartner I, von Hochstetter A, Baumert B, Luetolf U, Follath F. Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lau SK, Chu PG, Weiss LM. Immunohistochemical expression of Langerin in Langerhans cell histiocytosis and non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disorders. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:615-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Moore K, Kleijmeer M, Liu Y, Duvert-Frances V, Vincent C, Schmitt D, Davoust J, Caux C, Lebecque S, Saeland S. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 729] [Cited by in RCA: 687] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Girschikofsky M, Arico M, Castillo D, Chu A, Doberauer C, Fichter J, Haroche J, Kaltsas GA, Makras P, Marzano AV, de Menthon M, Micke O, Passoni E, Seegenschmiedt HM, Tazi A, McClain KL. Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, Calicchio ML, Kuo FC, Ligon AH, Stevenson KE, Kehoe SM, Garraway LA, Hahn WC, Meyerson M, Fleming MD, Rollins BJ. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 783] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Berres ML, Lim KP, Peters T, Price J, Takizawa H, Salmon H, Idoyaga J, Ruzo A, Lupo PJ, Hicks MJ, Shih A, Simko SJ, Abhyankar H, Chakraborty R, Leboeuf M, Beltrão M, Lira SA, Heym KM, Bigley V, Collin M, Manz MG, McClain K, Merad M, Allen CE. BRAF-V600E expression in precursor versus differentiated dendritic cells defines clinically distinct LCH risk groups. J Exp Med. 2014;211:669-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Diamond EL, Durham BH, Haroche J, Yao Z, Ma J, Parikh SA, Wang Z, Choi J, Kim E, Cohen-Aubart F, Lee SC, Gao Y, Micol JB, Campbell P, Walsh MP, Sylvester B, Dolgalev I, Aminova O, Heguy A, Zappile P, Nakitandwe J, Ganzel C, Dalton JD, Ellison DW, Estrada-Veras J, Lacouture M, Gahl WA, Stephens PJ, Miller VA, Ross JS, Ali SM, Briggs SR, Fasan O, Block J, Héritier S, Donadieu J, Solit DB, Hyman DM, Baselga J, Janku F, Taylor BS, Park CY, Amoura Z, Dogan A, Emile JF, Rosen N, Gruber TA, Abdel-Wahab O. Diverse and Targetable Kinase Alterations Drive Histiocytic Neoplasms. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:154-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McClain KL, Kozinetz CA. A phase II trial using thalidomide for Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:44-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cantu MA, Lupo PJ, Bilgi M, Hicks MJ, Allen CE, McClain KL. Optimal therapy for adults with Langerhans cell histiocytosis bone lesions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Simko SJ, McClain KL, Allen CE. Up-front therapy for LCH: is it time to test an alternative to vinblastine/prednisone? Br J Haematol. 2015;169:299-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Derenzini E, Fina MP, Stefoni V, Pellegrini C, Venturini F, Broccoli A, Gandolfi L, Pileri S, Fanti S, Lopci E, Castellucci P, Agostinelli C, Baccarani M, Zinzani PL. MACOP-B regimen in the treatment of adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis: experience on seven patients. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1173-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saven A, Burian C. Cladribine activity in adult langerhans-cell histiocytosis. Blood. 1999;93:4125-4130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, Laman JD, Claassen E. Differential In situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1999;94:4195-4201. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Caux C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Schmitt D, Banchereau J. GM-CSF and TNF-alpha cooperate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans cells. Nature. 1992;360:258-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1180] [Cited by in RCA: 1162] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alioua Z, Hjira N, Oumakhir S, Frikh R, Ghfir M, Rimani M, Sedrati O. [Thalidomide in adult multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report]. Rev Med Interne. 2006;27:633-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ruiz Beguerie J, Fernández J, Stringa MF, Anaya J. Vulvar Langerhans cell histiocytosis and thalidomide: an effective treatment option. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:324-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bensaid P, Machet L, Vaillant L, Machet MC, Scotto B, Lorette G. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis in the adult: regressive parotid involvement following thalidomide therapy. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119:281-283. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Broekaert SM, Metzler G, Burgdorf W, Röcken M, Schaller M. Multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis: successful treatment with thalidomide. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:311-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bouyssou-Gauthier ML, Bedane C, Jaccard A, Dang PM, Labrousse F, Leboutet MJ, Bernard P, Bonnetblanc JM. [Multicentric histiocytosis with hematological involvement]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:460-463. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Claudon A, Dietemann JL, Hamman De Compte A, Hassler P. [Interest in thalidomide in cutaneo-mucous and hypothalamo-hypophyseal involvement of Langerhans cell histiocytosis]. Rev Med Interne. 2002;23:651-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dallafior S, Pugin P, Cerny T, Betticher D, Saurat JH, Hauser C. [Successful treatment of a case of cutaneous Langerhans cell granulomatosis with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine and thalidomide]. Hautarzt. 1995;46:553-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | El-Safadi S, Dreyer T, Oehmke F, Muenstedt K. Management of adult primary vulvar Langerhans cell histiocytosis: review of the literature and a case history. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;163:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fernandes LB, Guerra JG, Costa MB, Paiva IG, Duran FP, Jacó DN. Langerhans cells histiocytosis with vulvar involvement and responding to thalidomide therapy--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:S78-S81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gerlach B, Stein A, Fischer R, Wozel G, Dittert DD, Richter G. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the elderly. Hautarzt. 1998;49:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gnassia A, Gnassia R, Bovalent D, Puissant A, Goudal H. Histiocytosys X avec "granulome eosinophile vulvarâ: effect spectaculaire du thalidomide. Ann Dermatol Vénéréol. 1987;114:1387-1389. |

| 28. | Kolde G, Schulze P, Sterry W. Mixed response to thalidomide therapy in adults: two cases of multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:384-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lair G, Marie I, Cailleux N, Blot E, Boullié MC, Courville P, Lauret P, Lévesque H, Courtois H. [Langerhans histiocytosis in adults: cutaneous and mucous lesion regression after treatment with thalidomide]. Rev Med Interne. 1998;19:196-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li R, Lin T, Gu H, Zhou Z. Successful thalidomide treatment of adult solitary perianal Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:391-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mauro E, Fraulini C, Rigolin GM, Galeotti R, Spanedda R, Castoldi G. A case of disseminated Langerhans' cell histiocytosis treated with thalidomide. Eur J Haematol. 2005;74:172-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Meunier L, Marck Y, Ribeyre C, Meynadier J. Adult cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: remission with thalidomide treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Misery L, Larbre B, Lyonnet S, Faure M, Thivolet J. Remission of Langerhans cell histiocytosis with thalidomide treatment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Moravvej H, Yousefi M, Barikbin B. An unusual case of adult disseminated cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:13. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Mortazavi H, Ehsani A, Namazi MR, Hosseini M. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:18. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Padula A, Medeiros LJ, Silva EG, Deavers MT. Isolated vulvar Langerhans cell histiocytosis: report of two cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:278-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sander CS, Kaatz M, Elsner P. Successful treatment of cutaneous langerhans cell histiocytosis with thalidomide. Dermatology. 2004;208:149-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Santillan A, Montero AJ, Kavanagh JJ, Liu J, Ramirez PT. Vulvar Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:241-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shahidi-Dadras M, Saeedi M, Shakoei S, Ayatollahi A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: an uncommon presentation, successfully treated by thalidomide. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:587-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Subramaniyan R, Ramachandran R, Rajangam G, Donaparthi N. Purely cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as an ulcer on the chin in an elderly man successfully treated with thalidomide. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:407-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Szturz P, Adam Z, Rehák Z, Koukalová R, Slaisová R, Stehlíková O, Chovancová J, Klabusay M, Krejčí M, Pour L, Hájek R, Mayer J. Lenalidomide proved effective in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:412-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Thomas L, Ducros B, Secchi T, Balme B, Moulin G. Successful treatment of adult's Langerhans cell histiocytosis with thalidomide. Report of two cases and literature review. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1261-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Viraben R, Dupre A, Gorguet B. Pure cutaneous histiocytosis resembling sinus histiocytosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:197-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wollina U, Kaatz M, Krönert C, Schönlebe J, Schmalenberg H, Schreiber G, Köstler E, Haroske G. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis with subsequent development of haematological malignancies. Report of two cases. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2006;15:79-84. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Crickx E, Bouaziz JD, Lorillon G, de Menthon M, Cordoliani F, Bugnet E, Bagot M, Rybojad M, Mourah S, Tazi A. Clinical Spectrum, Quality of Life, BRAF Mutation Status and Treatment of Skin Involvement in Adult Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:838-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Lancet. 1987;1:208-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Broadbent V, Gadner H. Current therapy for Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:327-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Tazi A, Lorillon G, Haroche J, Neel A, Dominique S, Aouba A, Bouaziz JD, de Margerie-Melon C, Bugnet E, Cottin V, Comont T, Lavigne C, Kahn JE, Donadieu J, Chevret S. Vinblastine chemotherapy in adult patients with langerhans cell histiocytosis: a multicenter retrospective study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, Arnaud L, Maksud P, Charlotte F, Cluzel P, Drier A, Hervier B, Benameur N, Besnard S, Donadieu J, Amoura Z. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kobayashi M, Tojo A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: Advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3707-3713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |