Revised: December 23, 2013

Accepted: January 17, 2014

Published online: May 6, 2014

Processing time: 242 Days and 22.4 Hours

An 11-year-old boy with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) contracted disseminated candidiasis during induction therapy, which was complicated with rupture of a fungal cranial aneurysm. Ventricular drainage and coil embolization of a residual aneurysm in combination with intensive antifungal therapy rescued the patient. Although clinical improvement was achieved, high fever and elevated levels of C-reactive protein and β-D-glucan continued for more than 10 mo. One year later, the ALL relapsed during maintenance therapy with methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine. After salvage chemotherapy, the patient received unrelated bone marrow transplantation (BMT) in a non-complete remission condition and survived. During subsequent chemotherapy and BMT, no recurrence of the fungal infection was observed under the prophylactic anti-fungal therapy with micafungin.

Core tip: Chronic disseminated candidiasis and resulting fungal intracranial aneurysm is a life-threatening complication during the induction therapy of leukemia with a poor survival rate. However, intensive and patient anti-fungal treatment made the patient receive unrelated bone marrow transplantation successfully.

- Citation: Okawa T, Ono T, Endo A, Takagi M, Nagasawa M. Chronic disseminated candidiasis complicated with a ruptured intracranial fungal aneurysm in ALL. World J Hematol 2014; 3(2): 44-48

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6204/full/v3/i2/44.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5315/wjh.v3.i2.44

Disseminated fungal infection in acute leukemia patients is a serious complication, not only because it is difficult to manage and cure, but it also interferes with continuation and completion of the standard treatment regimen for leukemia, which consequently leads to an unfavorable outcome. We experienced an acute lymphocytic leukemia child who contracted a disseminated candidiasis with a resultant rupture of intracranial fungal aneurysm during the induction chemotherapy. Our clinical experience in this patient is very useful and informative for physicians in this field.

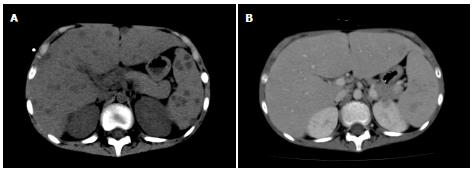

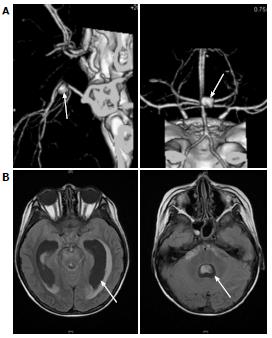

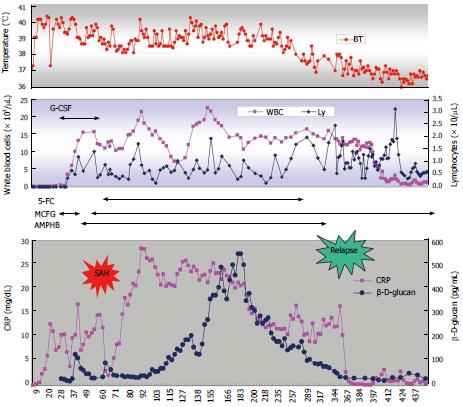

An 11-year-old boy with B-precursor acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) was admitted to our hospital. After confirming a good response to preceding prednisolone, TCCSG L09-16 (UMIN000003375) high risk (HR) induction chemotherapy was started. Two weeks later, the patient’s white blood cell count (WBC) fell below 100/μL and fever was noted on day 19. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 2.38 mg/dL. Intravenous antibiotic [cefpirome sulfate (CPR)] was started on the same day. On the 22nd d, the patient’s β-D-glucan level was below 6.0 pg/mL. Panipenem/betamipron (PAPM/BP) was administered instead of CPR, but changed to meropenem. Micafungin (MCFG; 6 mg/kg per day) was added and induction therapy was discontinued on the 29th d. The values of β-D-glucan and CRP increased to 27.4 pg/mL and 10.52 mg/dL, respectively, on the same day. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was started on the 37th day and liposomal amphotericin B (L-AMB; 6 mg/kg per day) was administered instead of MCFG on the 40th day. Whole-body computed tomography (CT) on the 40th day revealed no diagnostic findings. WBC increased to 3500/μL (neutrophils > 90%) on the 44th d. MCFG was re-started on the 48th d in addition to L-AMB. Although a repeated blood culture was negative, serum Candida antigen value was greater than 2 ng/mL on the 49th d. On the 51st d, the patient began to complain of an intermittent temporal headache. Whole-body CT on the 54th d revealed multiple lesions in the liver (Figure 1) and flucytosine (5-FC; 150 mg/kg per day) was added. On the 56th day, the patient’s consciousness level suddenly dropped and he experienced vomiting and incontinence. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 2) indicated subarachnoid hemorrhage and drainage from both lateral ventricles was performed. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was bloody and negative for bacteria and fungi. On the next day, brain angiography revealed an aneurysm with a diameter of 7 mm on the right basilar artery and coil embolization was successfully performed on the same day.

The patient’s condition was stabilized. His consciousness level occasionally fluctuated according to increased ventricular pressure, which rapidly improved on adjustment of ventricular drainage.

Because induction therapy for ALL was discontinued, maintenance therapy consisting of daily 6-mercaptopurine and weekly methotrexate was started on the 76th d. High-grade fever and elevated CRP levels were sustained, although the patient was clinically improving. Unexpectedly, the plasma β-D-glucan level gradually increased to more than 500 pg/mL. A CT scan on the 265th d revealed complete disappearance of multiple lesions in the liver. Five months later, CRP and β-D-glucan levels began to decrease slowly. 5-FC and L-AMB were discontinued on the 265th d and 335th d, respectively (Figure 3). On the 319th d, a ventricle-peritoneal shunt was performed. Ten months later, WBC gradually decreased with the progression of thrombocytopenia. A bone marrow examination on the 356th d confirmed the first relapse of ALL. Although the patient’s β-D-glucan level was still above 50 pg/mL, induction therapy based on the BFM95 protocol was started. After being in remission, he relapsed on the 680th d and on the 825th d. He received unrelated bone marrow transplantation (BMT) during non-remission status on the 839th d with a myeloablative conditioning regimen consisting of total body irradiation (TBI; 12 Gy), cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg × 2) and etoposide (60 mg/kg). Graft versus host disease prophylaxis consisted of tacrolimus and short term methotrexate. Engraftment was on the 16th d and he became free of red cell and platelet cell transfusion on the 15th and 37th d after BMT respectively. He has been in remission for more than 3 mo after BMT. During the subsequent chemotherapy/BMT and thereafter, no recurrence of fungal infection was observed under the prophylactic use of MCFG.

Fungal infections account for 4% to 9% of neutropenic infections in patients with hematological malignancy[1]. Additionally, it has been reported that patients with ALL are at the highest risk for invasive candidiasis during the neutropenic period following induction chemotherapy[2]. Disseminated candidiasis is a rare, life-threatening extended form of Candida infection and its mortality exceeds 10%-50%[3]. Fungal aneurysms of the intracranial circulation are an extremely rare complication and clinically differ from the more common bacterial “mycotic” aneurysms, which are usually associated with infectious endocarditis[4-6]. Contrary to bacterial “mycotic” aneurysms, fungal aneurysms usually affect the circle of Willis and the proximal arterial tree, and surgical treatment is extremely difficult[6]. Mortality related to fungal aneurysms is extremely high and it exceeds 80%-90% when the aneurysms rupture[7,8]. According to the literature, cases of pediatric fungal aneurysm are very rare and most of them are complicated in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, a rare primary immunodeficiency[9-11].

In our case, progression of disseminated candidiasis occurred within 3 wk after chemotherapy, which seems relatively fast. Once disseminated, a great deal of time is needed to treat the fungal infection even when the neutrophil count recovers[12]. It is known that liver lesions are not apparent under agranulocytic conditions because of the lack of inflammation[13]. It may be possible that an increase in neutrophils induces excessive inflammation, which sometimes results in tissue destruction. With intensive anti-fungal chemotherapy and surgical and endovascular treatment, our patient survived through the early critical episode. However, the subsequent clinical course of the patient was difficult and challenging. Once CRP and β-D-glucan levels decreased after surgery, the CRP level increased again above 20 mg/dL and the β-D-glucan level increased gradually. Additionally, high fever continued for months.

In our case, clinical evidence of disseminated candidiasis was based on elevated β-D-glucan levels, the presence of serum Candida antigen and multiple liver lesions. Repeated blood or CSF cultures could not detect Candida spp. It has been reported that the positive predictive value of blood cultures for Candida is relatively low and the typical findings of a CT scan are clinically valuable for diagnosis with serological data[13]. Although histological and microbiological evidence could not be obtained, it is more likely that intracranial aneurysm was due to disseminated candidiasis from the clinical point of view.

Guidelines for disseminated candidiasis recommend fluconazole, amphotericin B, voriconazole or caspofungin[14,15]. MCFG was recently reported to be as effective as caspofungin[16]. Because some strains of Candida, such as C. glabrata and C. krusei, are resistant to fluconazole, we selected a higher dose of MCFG for the first-line therapy. Considering the severity of infection, we added L-AMB to MCFG. Although elevated CRP and β-D-glucan levels with high fever continued as shown in Figure 3, the patient was clinically improving and we continued anti-fungal therapy. It is well known that humans do not produce enzymes that metabolize β-D-glucan. There may be 2 possible explanations for why β-D-glucan was increasing in the middle of the treatment course: one is that the destruction of Candida was accelerated at that time and another is that the Candida antigen was sequestered from circulation and drained into systemic circulation at that time. In light of the sustained high level of CRP and its later decrease in parallel with β-D-glucan, the former scenario seems to be more likely.

Fortunately, our patient survived and received BMT successfully with no recurrence of candidiasis or other fungal infections under the prophylactic use of MCFG thereafter. He has been in remission for more than 3 mo after BMT, although we have to be careful how long the patient remains in remission. With the recent advance of anti-fungal drugs, disseminated candidiasis is still a challenging complication during the treatment of hematological malignancy and is difficult to manage. However, intensive patient treatment has enabled us to accomplish chemotherapy and BMT successfully even in a high-risk patient with ALL[17].

An 11-year-old boy with acute lymphocytic leukemia who suffered from chronic disseminated candidiasis during remission induction chemotherapy.

Chronic disseminated candidiasis and fungal intracranial aneurysm and its rupture.

Bacterial infection and intracranial hemorrhage due to granulocytopenia and thrombocytopenia

Increased β-D-glucan and candida antigen in the serum

Whole computed tomography scan revealed multiple masses in the liver. Angiography disclosed intracranial aneurysm.

Coiled embolization and long-term chemotherapy with combination of multiple anti-fungal drugs

This case report emphasizes the difficulties of management of fungal infection during the chemotherapy of leukemia. Once it has occurred, not only control of fungal infection but also the control of leukemia is disturbed. However, bone marrow transplantation is not a contraindicated choice of therapy.

This article is well described and some important messages emerge. This paper will therefore be very useful for hematologists and infectiologists.

P- Reviewers: Uderzo C, Zimmer J S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Castagnola E, Cesaro S, Giacchino M, Livadiotti S, Tucci F, Zanazzo G, Caselli D, Caviglia I, Parodi S, Rondelli R. Fungal infections in children with cancer: a prospective, multicenter surveillance study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Thaler M, Pastakia B, Shawker TH, O’Leary T, Pizzo PA. Hepatic candidiasis in cancer patients: the evolving picture of the syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:88-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hassan I, Powell G, Sidhu M, Hart WM, Denning DW. Excess mortality, length of stay and cost attributable to candidaemia. J Infect. 2009;59:360-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eishi K, Kawazoe K, Kuriyama Y, Kitoh Y, Kawashima Y, Omae T. Surgical management of infective endocarditis associated with cerebral complications. Multi-center retrospective study in Japan. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:1745-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oohara K, Yamazaki T, Kanou H, Kobayashi A. Infective endocarditis complicated by mycotic cerebral aneurysm: two case reports of women in the peripartum period. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14:533-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Watson JC, Myseros JS, Bullock MR. True fungal mycotic aneurysm of the basilar artery: a clinical and surgical dilemma. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;9:50-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hurst RW, Judkins A, Bolger W, Chu A, Loevner LA. Mycotic aneurysm and cerebral infarction resulting from fungal sinusitis: imaging and pathologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:858-863. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Regelsberger J, Elsayed A, Matschke J, Lindop G, Grzyska U, van den Boom L, Venne D. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations for “mycotic” cerebral aneurysms: 2 case reports and review of the literature. Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2011;72:138-143. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Marazzi MG, Bondi E, Giannattasio A, Strozzi M, Savioli C. Intracranial aneurysm associated with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:461-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Leroy D, Dompmartin A, Houtteville JP, Theron J. Aneurysm associated with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis during long-term therapy with ketoconazole. Dermatologica. 1989;178:43-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Loeys BL, Van Coster RN, Defreyne LR, Leroy JG. Fungal intracranial aneurysm in a child with familial chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:650-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kontny U, Walsh TJ, Rossler J, Uhl M, Niemeyer CM. Successful treatment of refractory chronic disseminated candidiasis after prolonged administration of caspofungin in a child with acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:360-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Semelka RC, Kelekis NL, Sallah S, Worawattanakul S, Ascher SM. Hepatosplenic fungal disease: diagnostic accuracy and spectrum of appearances on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1311-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ascioglu S, Rex JH, de Pauw B, Bennett JE, Bille J, Crokaert F, Denning DW, Donnelly JP, Edwards JE, Erjavec Z. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1840] [Cited by in RCA: 1797] [Article Influence: 78.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, Mullen CA, Raad II, Rolston KV, Young JA, Wingard JR. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e56-e93. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Spellberg BJ, Filler SG, Edwards JE. Current treatment strategies for disseminated candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:244-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Masood A, Sallah S. Chronic disseminated candidiasis in patients with acute leukemia: emphasis on diagnostic definition and treatment. Leuk Res. 2005;29:493-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |