Peer-review started: August 26, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 12, 2022

Accepted: November 29, 2022

Article in press: November 29, 2022

Published online: January 5, 2023

Processing time: 130 Days and 11 Hours

Typhoid fever is a public health problem in Asia and Africa. Pancytopenia has been rarely reported during the 20th century. Reports during the last 20 years are scarce.

Our first patient was a young adult male presenting with febrile neutropenia whose blood and bone marrow cultures grew Salmonella typhi. He recovered before discharge from the hospital. The second was a primigravida who had an abortion following a febrile illness and was found to have pancytopenia. The Widal test showed high initial titers, and she was presumptively treated for typhoid. Convalescence showed a doubling of Widal titers.

Typhoid fever continued to show up as a fever with cytopenia demanding significant effort and time in working up such patients. In developing countries, the liaison with typhoid continues.

Core Tip: Despite the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, typhoid fever remains a cause of acute febrile illness and cytopenia. Typhoid fever can rarely cause pregnancy loss, so acute febrile illnesses in pregnancy should not be neglected. Even with significant improvements in sanitation and water supply, contaminated food remains a problematic source of typhoid fever.

- Citation: Saha RN, Selvaraj J, Viswanathan S, Pillai V. Typhoid with pancytopenia: Revisiting a forgotten foe: Two case reports. World J Hematol 2023; 10(1): 9-14

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6204/full/v10/i1/9.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5315/wjh.v10.i1.9

Typhoid fever is a disease specific to humans and is usually spread by contaminated food and water. It often requires a small infectious dose. It remains a public health nuisance in South Asian countries like India[1]. The most recent incidence among Indian centers was 497 typhoid cases per 100000 per year[2]. It can present many symptoms, predominantly related to the gastrointestinal system, but can range from encephalopathy to a urinary tract infection[3].

Pancytopenia is a rarely noted complication (6.2%-8.3%)[4]. Isolated thrombocytopenia is a common manifestation and mimics other causes of fever in the tropics such as dengue, scrub typhus, malaria, and leptospirosis[5]. Hemophagocytosis, bone marrow suppression, and disseminated intravascular coagulation are commonly speculated causes of pancytopenia[6]. Reports of pancytopenia in enteric fever during the last 20 years are scarce. Herein, we present 2 cases of pancytopenia in adults associated with typhoid fever: One presented as febrile neutropenia, and the other presented as septic abortion.

Case 1: An 18-year-old boy working in a courier company in Bangalore presented with a history of high-grade intermittent fever for 14 d.

Case 2: A 27-year-old housewife from Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu, primigravida at 12 wk pregnancy, presented with a history of fever of 1 wk, spotting per vaginum for 3 d, and cough for 1 d.

Case 1: Five days following the onset of fever, he developed constipation; nausea and anorexia were also present. He was admitted to a nearby hospital for the preceding 5 d before presentation, where his complete blood count (CBC) revealed hemoglobin of 81 g/L (normal range: 14-16 g/L), total leukocyte counts (TLC) of 0.8 × 109/L (normal range: 4.5-11.0 × 109/L), absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 0.5 × 109/L, and platelets of 15 × 109/L (normal range: 150-400 × 109/L). Then he was referred to our center. Dengue and Widal tests were negative; the rapid antigen test for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was negative. High-resolution computed tomography thorax was normal. He had not been admi-nistered any antibiotics before his arrival. He did not give any other history to suggest localization of the fever at admission to our hospital. There were no bleeding manifestations, but he had fatigue upon minimal exertion.

Case 2: She had consulted her obstetrician for spotting; the ultrasonogram showed a single intrauterine gestation without fetal cardiac activity. A CBC in the same hospital showed pancytopenia, with hemoglobin of 90 g/L, TLC of 2.3 × 109/L, ANC of 1.07 × 109/L, and platelets of 90 × 109/L. She was referred for pancytopenia with incomplete abortion.

Case 1: No significant personal and family history.

Case 2: She was a primigravida.

Case 1: On examination, he had tachycardia of 99 beats/min, fever of 104.6 °F, multiple small (< 1 cm) lymph nodes in both axillary and inguinal regions, and mild splenomegaly (2 cm).

Case 2: At presentation (on day 8 of illness), she looked toxic, with a fever of 103 °F, pulse rate of 140 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/75 mmHg, and a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min. She was admitted into the obstetrics intensive care unit. On examination, she had a palpable spleen of 2 cm, with an otherwise soft abdomen. There was minimal bleeding through the cervical, and it was open. The uterus was approximately 12 wk, with bilateral fornices free and non-tender on insertion of the tip of the finger, and clots were present in the uterine cavity.

Case 1: Repeat CBC after admission showed hemoglobin of 78 g/L, corrected reticulocyte counts of 0.2%, TLC of 1.67 × 109/L, ANC of 1.0 × 109/L, and platelets of 30 × 109/L. A peripheral smear showed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia without blast cells.

Case 2: The CBC in our hospital revealed hemoglobin of 74 g/L, TLC of 1.16 × 109/L, ANC of 0.67 × 109/L, and platelets of 80 × 109/L. Peripheral smear showed microcytic hypochromic red blood cells and mild anisopoikilocytosis without blasts.

Renal and liver function tests were non-contributory. Lactate dehydrogenase was 670 IU/L. Because of the patient’s cough, reverse transcription PCR for COVID-19 was repeated twice and was negative. Chest radiography and high-resolution computed tomography thorax were non-contributory. Serology for toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, and HIV was also negative.

On admission, the procalcitonin value was 0.48 ng/mL (normal range: < 0.05 ng/mL).

Case 1: Acute leukemia with febrile neutropenia and an acute febrile illness causing probable hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis was considered.

Case 2: The Widal test showed Salmonella typhi O agglutinin and H agglutinin titers of 1:320 and 1:320, respectively, suggestive of typhoid fever.

Case 1: Piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5g Q8h and amikacin 600 mg OD were initiated intravenously. His direct Coombs test was negative. Lactate dehydrogenase of 1441 IU/L (normal range: 140-300 IU/L), ferritin of 6509 ng/mL (25-300 ng/mL), and triglycerides of 151 mg/dL were seen. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed on day 2; aspiration was reported as a reactive marrow with relative lymphocytosis on day 3. On day 4, peripheral blood culture grew Salmonella enterica serovar typhi sensitive to ceftriaxone, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin. On reviewing his history, he said he frequented the roadside food stalls near his workplace for the last 2 mo to eat fried rice, noodles, and beef. An abdominal ultrasound showed only mild fatty liver with mild splenomegaly. Thus, antibiotics were switched to ceftriaxone 2 g intravenously OD on day 4. Bone marrow culture also grew the same organism on day 5.

Case 2: Two packed red blood cells and two platelets were transfused. Dilatation and curettage was performed. Pending cultures of blood, urine, and a high vaginal swab, she was empirically initiated on ceftriaxone 2 g intravenously once daily and metronidazole 500 mg IV q8H. A medicine consultation was sought on day 2 of admission for febrile neutropenia. Piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5g IV Q8H and tab azithromycin 500 mg OD were suggested, pending reports of cultures, echocardiography, disseminated intravascular coagulation panel, and febrile panel (dengue, scrub IgM PCR, chikungunya IgM, and Widal). Cultures of blood, urine, and products of conception were sterile; the high transvaginal swab revealed commensal organisms. Echocardiography was normal. D-dimers and fibrinogen were normal.

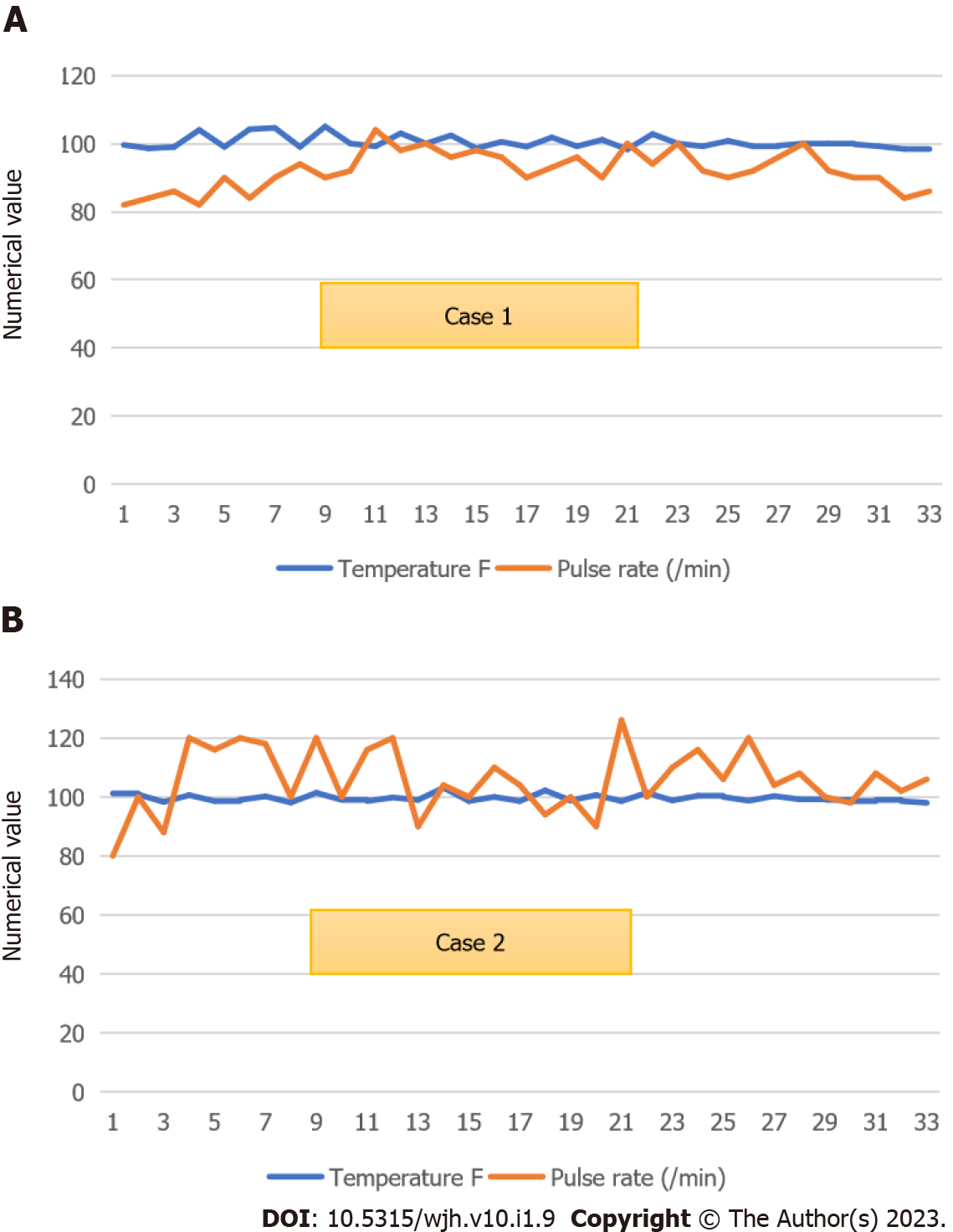

Case 1: He became afebrile on day 6 (Figure 1A). He was eating well by day 10 of ceftriaxone. His father requested discharge on day 12 due to an impending lockdown to complete antibiotics at a nearby health center. Bone marrow biopsy showed normocellular active marrow with epithelioid cell granuloma.

One week later, when contacted by telephone, he was asymptomatic and was staying at home. He could not come back to the hospital for repeat blood counts.

Case 2: The obstetrician had not initiated piperacillin-tazobactam, and we were asked to transfer the patient to our department on day 6 of admission, considering the pancytopenia, negative cultures, and positive Widal.

We reviewed the patient again on the same day; her cough had subsided, her oral intake had improved, and the toxic appearance was absent. We transferred her to the Medicine ward and continued to treat typhoid fever presumptively. She later said she had been eating dinner in restaurants during Ramadan. By day 7, she had become afebrile (Figure 1B). She was not willing to submit to a bone marrow biopsy since she felt she was improving. Repeat procalcitonin on day 9 of admission was 0.05 ng/mL. After being observed for 2 afebrile days, she was discharged on day 11 to complete 3 d of ceftriaxone at a nearby hospital. At discharge, her CBC showed hemoglobin of 100 of g/L, TLC of 2.56 × 109/L, ANC of 1.6 × 109/L, and platelets of 230 × 109/L.

One week later, her mother returned to the hospital to show a CBC that had a resolution of pancytopenia. The Widal test repeated 1 wk after discharge (day 17 of admission) showed titers of Salmonella typhi O agglutinin 1:640 and Salmonella typhi H agglutinin 1:640.

The first patient presented in the 3rd wk of illness without other complaints such as diarrhea, abdominal distension, or confusion. The second patient presented during the 2nd week only with fever, cough, and toxemia, which had probably caused an abortion (and also mimicked COVID-19). Good response to antibiotics was observed in both patients and was associated with a significant improvement in cytopenia that reflected the results of previous studies[7]. Both patients had a history of eating food from possibly unhygienic food outlets. The COVID-19-related lockdowns and shutting down of restaurants have led to roadside fast-food stalls remaining as the sole option for getting meals for a section of the population.

Pancytopenia with an acute febrile illness could be due to either viral, bacterial, parasitic, mycobacterial, or fungal infections. Common tropical acute febrile diseases such as dengue, leptospirosis, scrub typhus, and malaria were ruled out in our patients. Viral serologies for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C were negative. Cultures of blood and fluids were sterile in the second patient, while they gave us the diagnosis for the first. Pancytopenia due to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis was considered in the first patient[8]. Fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, and elevated ferritin were present, while triglycerides were normal. We could not evaluate natural killer cell cytotoxicity and elevated soluble CD25 since they were unavailable in our hospital. The Widal test was sent for the female patient because she had been buying dinner from food stalls regularly during Ramadan.

Typhoid fever and pancytopenia have been described in some reports from Asia and Africa during the last two decades of the 20th century. In the previous 20 years, there has been only one report each from India[9], Pakistan[8], Nepal[6], Ghana[10], Malawi[11], Spain[12], Turkey[13], and the United States[14]. Barring Nepal and the African countries, the presentation of all patients was with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pakistan, Nepal, Malawi, Turkey, and Spain described pediatric patients, while the remaining three described young adults. The patient from the United States was also an Indian who had arrived in the country just 2 d before admission, making this report the fourth among adults in the last 20 years. Considering the prevalence of typhoid fever, this is extremely rare.

Bone marrow findings commonly described in typhoid fever include chronic inflammation, hemophagocytosis, or a reactive picture. We continued with bone marrow in the first patient since there was a working diagnosis of acute leukemia. In the second case, bone marrow was not performed since she had already received antibiotics for 6 d and was showing an improving trend. More ever, she did not consent to the procedure. Bone marrow findings have been classified based on duration from symptom onset into the early phase (showing classically granulocytic hyperplasia with a mild degree of mono histiocytic proliferation until about 10 d from symptom onset), and proliferative phase from 10-25 d, wherein active hemophagocytosis is the characteristic finding. Beyond 25 d, it is categorized as the lysis phase, with well-formed granulomata typical of this phase. Bone marrow changes generally resolve completely following treatment[15]. In the first case, bone marrow showed only mild erythroid hyperplasia with toxic leukocytosis. Therefore, it can be classified as the proliferative phase with an active infection, which is effectively treated by sensitive antibiotics. Peripheral destruction is probably an added component based on increased lactate dehydrogenase and splenomegaly findings.

The Widal test was the only basis for diagnosis in the second patient. Though a single Widal test has often been used controversially to diagnose typhoid fever in developing countries, we presumptively treated her as such. There was no past vaccination for typhoid, and other infections such as malaria, which can cause false-positive results, were ruled out[16]. A doubling of titers 17 d after the first sample was probably suggestive.

Though septic abortion can be linked with typhoid fever, the culture of the products of conception did not reveal anything significant. Typhoid fever has been associated with premature abortions, most of them in the pre-antibiotic era[17]. Typhoid fever can significantly complicate pregnancy leading to abortion, fetal death, and neonatal infection as well as worsen the maternal prognosis.

We report 2 cases with typhoid fever and pancytopenia presenting differently, both of whom typhoid was not entertained as the initial diagnosis. One was a confirmed case, while the other had probable typhoid fever. Typhoid fever continues to show up as fever with cytopenia demanding significant effort and time in working up such patients. In developing countries, the liaison with typhoid continues.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Physicians; Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen C, China; Vyshka G, Albania S-Editor: Liu GL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu GL

| 1. | Balaji V, Kapil A, Shastri J, Pragasam AK, Gole G, Choudhari S, Kang G, John J. Longitudinal Typhoid Fever Trends in India from 2000 to 2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Marchello CS, Hong CY, Crump JA. Global Typhoid Fever Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:S105-S116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Crump JA, Sjölund-Karlsson M, Gordon MA, Parry CM. Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Laboratory Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Antimicrobial Management of Invasive Salmonella Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:901-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 700] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 71.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dutta TK, Beeresha, Ghotekar LH. Atypical manifestations of typhoid fever. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:248-251. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lakshmi MS, Rao GS. Evaluation of clinical profile of fever with thrombocytopenia in patients attending GIMSR, Visakhapatnam. Int J Contempor Med Surg Radiol. 2020;5:A102-A106.. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Pathak R, Sharma A, Khanal A. Enteric fever with severe pancytopenia in a four year girl. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2010;50:313-315. [PubMed] |

| 7. | James J, Dutta TK, Jayanthi S. Correlation of clinical and hematologic profiles with bone marrow responses in typhoid fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:313-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abbas A, Raza M, Majid A, Khalid Y, Bin Waqar SH. Infection-associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: An Unusual Clinical Masquerader. Cureus. 2018;10:e2472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ray U, Dutta S, Bandyopadhyay S, Mondal S. Uncommon presentation of a common tropical infection. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2020;63:161-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Anabire NG, Aryee PA, Helegbe GK. Hematological abnormalities in patients with malaria and typhoid in Tamale Metropolis of Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kumwenda M, Iroh Tam PY. An adolescent with multi-organ involvement from typhoid fever. Malawi Med J. 2019;31:159-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sánchez-Moreno P, Olbrich P, Falcón-Neyra L, Lucena JM, Aznar J, Neth O. Typhoid fever causing haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a non-endemic country - first case report and review of the current literature. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2019;37:112-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Şahin Yaşar A, Karaman K, Geylan H, Çetin M, Güven B, Öner AF. Typhoid Fever Accompanied With Hematopoetic Lymphohistiocytosis and Rhabdomyolysis in a Refugee Child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41:e233-e234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Non LR, Patel R, Esmaeeli A, Despotovic V. Typhoid Fever Complicated by Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Rhabdomyolysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:1068-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shin BM, Paik IK, Cho HI. Bone marrow pathology of culture proven typhoid fever. J Korean Med Sci. 1994;9:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Olopoenia LA, King AL. Widal agglutination test - 100 years later: still plagued by controversy. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hicks HT, French H. Typhoid fever and pregnancy, with special reference to fœtal infection. Lancet. 1905;165:1491-1493. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |