Revised: June 20, 2012

Accepted: July 26, 2012

Published online: August 2, 2012

Hidroacanthoma simplex (HAS) is a rare skin appendage tumor and is recognized as an intraepidermal variant of poroma. Pigmented HAS is an extremely rare variant with dendritic melanocytes and/or melanin pigment in the tumor cells and a few cases of pigmented HAS have been reported in the English literature. We herein report a case of pigmented HAS and discuss the clinicopathological features of pigmented HAS and the pitfall in the diagnosis of black lesions.

- Citation: Ishida M, Kojima F, Hotta M, Iwai Y, Okabe H. Pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex: A diagnostic pitfall. World J Dermatol 2012; 1(2): 10-12

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6190/full/v1/i2/10.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5314/wjd.v1.i2.10

Hidroacanthoma simplex (HAS) is a rare benign skin appendage tumor and is recognized as an intraepidermal variant of poroma[1]. Pigmented HAS is an extremely rare variant of HAS and a few cases of pigmented HAS have been reported in the English literature[2-6]. Herein, we report an additional case of pigmented HAS in a 73 years old Japanese woman and we discuss the clinicopathological features of pigmented HAS and the pitfall in the diagnosis of black lesions.

A 73 years old Japanese woman presented with a nodule on the anterior region of her right lower leg, which had first been noticed one year earlier. The lesion was a brown to black scaly dome-shaped nodule, measuring 12 mm × 8 mm in diameter, and no clinical symptoms, such as erosion and pain, were present. Macroscopic inspection led to the initial clinical diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis and total tumor resection was performed.

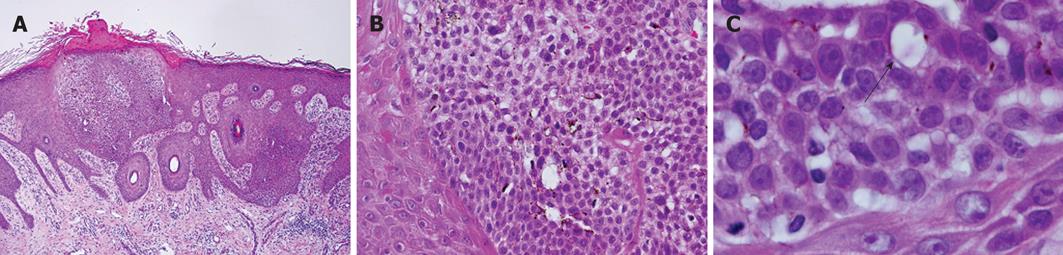

The histopathological study of the tumor revealed irregular elongation of the rete ridges, hyperkeratosis and intraepidermal proliferation of small-sized basaloid cells, which exhibited the so-called “Jadassohn phenomenon” (Figure 1A). The nuclei of the basaloid cells were round to oval and smaller than those of neighboring epidermal keratinocytes, although these cells had a small nucleolus (Figure 1B). Mitotic figures were rarely seen (< 1/10 high power fields). Dendritic melanocytes were scattered in the tumor nests but melanin pigment was not present in the cytoplasm of the basaloid cells (Figure 1B). Within the tumor nests, a few ductal structures were observed (Figure 1C). No invasive neoplastic growth was observed.

Immunohistochemical study showed that epithelial membrane antigen was expressed in approximately half of the tumor cells but no carcinoembryonic antigen-positive cells were found. Overexpression of p53 protein was not observed in the tumor cells. Melan-A was expressed in dendritic melanocytes.

Accordingly, the final diagnosis of pigmented HAS was made.

HAS is a rare benign skin appendage tumor, first described by Coburn et al[7] in 1956. HAS is recognized as an intraepidermal variant of poroma and thought to originate from the outer cells of the acrosyringium[1]. According to the report by Anzai et al[8] in which 70 Japanese cases of HAS were analyzed, the most common sites of HAS were the trunk (42.8%) and lower extremities (45.7%) and most lesions were clinically diagnosed as seborrheic keratosis or Bowen’s disease, whereas none were clinically diagnosed as HAS[8]. These results suggest that clinical diagnosis of HAS by macroscopic inspection is extremely difficult.

The most peculiar finding in the present case is the presence of dendritic melanocytes in the intraepidermal tumor nests. Although various benign and malignant cutaneous tumors often accompany non-neoplastic melanocytes, described as “melanocytic colonization”, poroma and HAS usually lack melanocytes and melanin pigment. However, a few cases of pigmented HAS, an extremely rare variant with dendritic melanocytes and/or melanin pigment in the tumor cells, have been reported in the English literature[2-6]. In the present case, intraepidermal proliferation of bland basaloid cells exhibiting the “Jadassohn phenomenon” was observed and the nuclei of these basaloid cells were smaller than those of neighboring epidermal keratinocytes. Further dendritic melanocytes were scattered within the tumor nests. These findings are similar to the characteristics of clonal type of seborrheic keratosis because HAS and clonal type of seborrheic keratosis exhibit an intraepidermal proliferation of small basaloid cells. However, a few ductal structures were observed; therefore, the clonal type of seborrheic keratosis was excluded and a final diagnosis of pigmented HAS made.

It is well known that HAS is often associated with porocarcinoma and that porocarcinoma shows aggressive clinical behavior. Snow et al[9] reported that approximately 20% of porocarcinoma recur after excision and regional lymph node metastases occurred in 20% of the cases, while 12% also showed distant metastases. The mortality rate exceeds 65% when regional lymph nodes are involved and the survival for patients with distant metastases is reported to be between 5 to 24 mo[9]. In addition, most of the reported cases of pigmented HAS had a malignant component[2-6] and we previously reported a case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented HAS, which led to death from multiple lymph node, bone and liver metastases[6]. Lee et al[10] recommended early wide local excision and careful attention in the case of HAS due to its potential risk of malignant change.

Dermoscopic findings of pigmented HAS have been reported[11]. Pigmented poroma, including HAS, mimics a number of skin tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis and malignant melanoma on dermoscopy[11]. Therefore, distinction between pigmented HAS and seborrheic keratosis may be challenging on dermoscopy.

In conclusion, it is important for dermatologists to take pigmented HAS into consideration in a differential diagnosis of black lesions because HAS, especially pigmented HAS, clinically resembles seborrheic keratosis and Bowen’s disease. In addition, it is important to completely resect HAS before malignant transformation and rapid progression to invasive porocarcinoma.

Peer reviewer: Giuseppe Argenziano, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Dermatology, Second University of Naples, Via G. Fiorelli 5, 80121 Naples, Italy

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Nakagawa T, Inai M, Yamamoto S, Takaiwa T. Hidroacanthoma simplex showing variation in the appearance of tumor cells in different nests. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:238-244. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Zina AM, Bundino S, Pippione MG. Pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with porocarcinoma. Light and electron microscopic study of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 1982;9:104-112. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ueo T, Kashima K, Daa T, Kondoh Y, Yanagi T, Yokoyama S. Porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:500-503. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lee WJ, Seo YJ, Yoon JS, Suhr KB, Lee JH, Park JK, Suh KS. Malignant hidroacanthoma simplex: a case report. J Dermatol. 2000;27:52-55. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lee JY, Lin MH. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex mimicking irritated seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:705-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, Okabe H. A case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with multiple lymph node, liver and bone metastases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Coburn JG, Smith JL. Hidroacanthoma simplex; an assessment of a selected group of intraepidermal basal cell epitheliomata and of their malignant homologues. Br J Dermatol. 1956;68:400-418. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Anzai S, Arakawa S, Fujiwara S, Yokoyama S. Hidroacanthoma simplex: a case report and analysis of 70 Japanese cases. Dermatology. 2005;210:363-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lee JB, Oh CK, Jang HS, Kim MB, Jang BS, Kwon KS. A case of porocarcinoma from pre-existing hidroacanthoma simplex: need of early excision for hidroacanthoma simplex. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:772-774. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Minagawa A, Koga H. Dermoscopy of pigmented poromas. Dermatology. 2010;221:78-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |