Peer-review started: February 6, 2018

First decision: March 2, 2018

Revised: April 24, 2018

Accepted: May 30, 2018

Article in press: May 30, 2018

Published online: July 18, 2018

Processing time: 162 Days and 11 Hours

To analyze the literature on efficacy of dynamamization vs exchange nailing in treatment of delayed and non-union femur fractures.

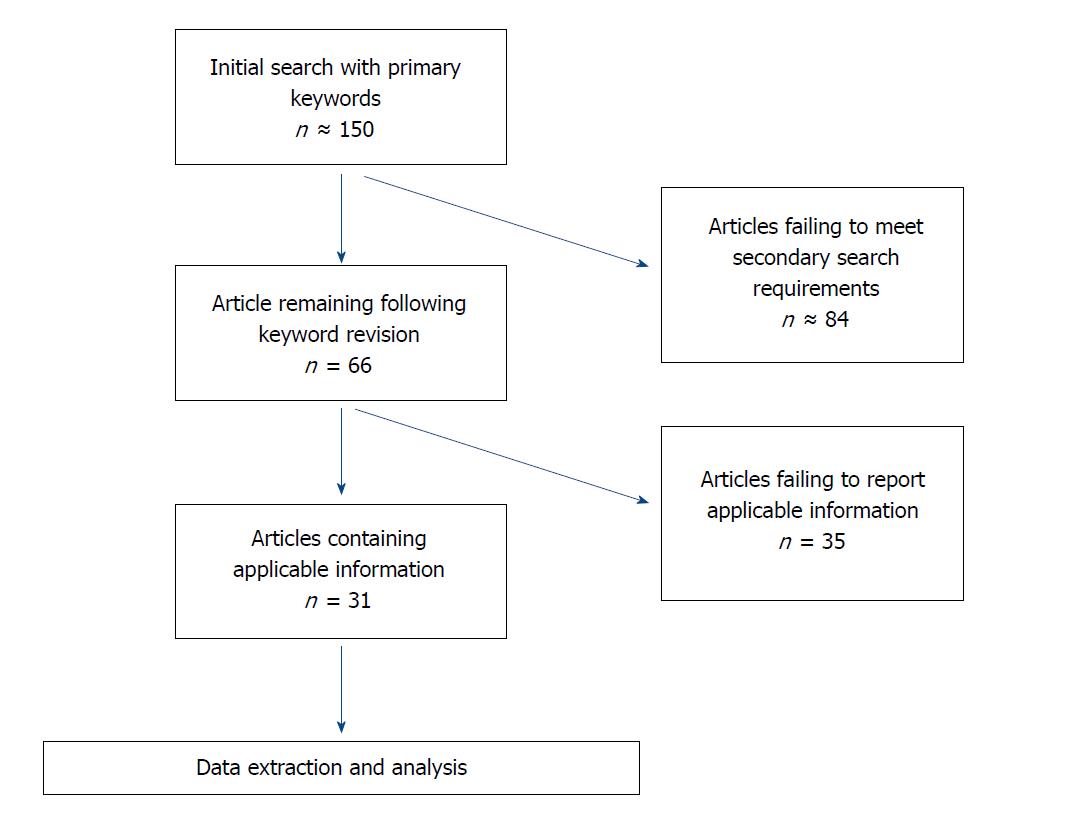

Ultimately, 31 peer-reviewed articles with 644 exchanged nailing patients and 131 dynamization patients were identified and analyzed. The following key words were inputted in different combinations in order to search the field of publications in its entirety: “non-union”, “delayed union”, “ununited”, “femur fracture”, “femoral fracture”, “exchange nailing”, “dynaiz(s)ation”, “secondary nailing”, “dynamic”, “static”, and “nail revision”. The initial search yielded over 150 results, and was refined based on the inclusion criteria: Only studies reporting on humans, non-unions and delayed unions, and the usage of exchange nailing and/or dynamization as a secondary treatment after failed IM nailing. The resulting 66 articles were obtained through online journal access. The results were filtered further based on the exclusion criteria: No articles that failed to report overall union rates, differentiate between success rates of their reported techniques, or articles that analyzed less than 5 patients.

Exchange nailing lead to fracture union in 84.785% of patients compared to the 66.412% of dynamization with statistically comparable durations until union (5.193 ± 2.310 mo and 4.769 ± 1.986 mo respectively). Dynamically locking exchange nails resulted in an average union time of 5.208 ± 2.475 mo compared to 5.149 ± 2.366 mo (P = 0.8682) in statically locked exchange nails. The overall union rate of the two procedures, statically and dynamically locked exchange nailing yielded union rates of 84.259% and 82.381% respectively. Therefore, there was no significant difference between the different locking methods of exchange nailing for union rate or time to union at a significance value of P < 0.05. The analysis showed exchange nailing to be the more successful choice in the treatment of femoral non-unions in respect to its higher success rate (491/567 EN, 24/57 dynam, P < 0.0001). However, there was no significant difference between the success rates of the two procedures for delayed union fractures (25/27 EN, 45/55 dynam, P = 0.3299). Nevertheless, dynamization was more efficient in the treatment of delayed unions (at rates comparable to exchange nailing) than in the treatment of non-unions.

In conclusion, after examination of factors, dynamization is recommended treatment of delayed femur fractures, while exchange nailing is the treatment of choice for non-unions.

Core tip: Information from previously published articles investigating patients treated for delayed union and non-union femur fractures by either dynamization or exchange nailing was combined and analyzed to better understand which technique was more efficient at achieving osseous union. When treating femoral non-unions, exchange nailing was shown to achieve osseous union in a higher percentage of patients than dynamization with comparable recovery times. However, dynamization appears to be equally as effective as exchange nailing in the treatment of delayed unions.

- Citation: Vaughn JE, Shah RV, Samman T, Stirton J, Liu J, Ebraheim NA. Systematic review of dynamization vs exchange nailing for delayed/non-union femoral fractures. World J Orthop 2018; 9(7): 92-99

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v9/i7/92.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v9.i7.92

Delayed union and non-union are two designations for the slowed or absent progression of callus formation and osseous healing in a fracture from 3-6 mo, and greater than 6 mo, respectively. Although IM nailing is an effective treatment method for femoral fractures with union rates reported between 90%-100%[1], non-union rates have increased due to the higher probability of survival in complex injuries and improved limb salvage techniques[2]. As a result, secondary surgical techniques have become increasingly important in achieving osseous union in femur fractures.

Two of the more common secondary surgical techniques used in the treatment of delayed union and non-union after IM nail failure are dynamization and exchange nailing. Dynamization involves the removal of proximal or distal locking screws in a statically locked IM nail allowing weight bearing to stimulate osseous growth at the fracture site. Previously, surgeons used this technique before delayed union occurred in an attempt to avoid complications and improve union rates. However, studies have failed to find any advantage to this choice[3], resulting in it mainly being used as a secondary treatment.

An alternate treatment strategy, exchange nailing, consists of the removal of the current IM nail, debridement of the medullary cavity, followed by insertion of a larger IM nail. This procedure utilizes reaming and increased fracture stability to stimulate osseous growth. Different variations of this procedure have been reported, with varying rates of success attributed to factors such as the use of bone grafting, size of medullary reaming, and different nail locking methods[4,5].

Unfortunately, the overall reported rates of successful unions achieved using these techniques range from 33.3%-90% in dynamization[6-12] and 28.6%-100% in exchange nailing[8,9,13-36]. Additional factors including infection, locations of injury, and major surgical complications have been reported at varying rates across literature resulting in a lack of consensus in the field[5].

The results of multiple studies were examined in an attempt to consolidate the published information across the field and clarify which procedure to use. Consolidation of these results into a larger subject pool across the existing literature increases the strength of its conclusions compared to individual reports. Additionally, the locking method of exchange nails, either static or dynamic, has been identified as a possible factor affecting union rates[5]. Dynamic locking attempts to combine these procedures in order to improve healing rates, as compared to static exchange nailing, but results have been varied. Finally, dynamization has been suggested to result in different rates of success between the treatments of delayed unions in comparison to non-unions[1]. This may allow procedures to be utilized more effectively, based on the different progressions of patients’ injuries. Currently there is lack updated systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic in the literature. This systematic review and meta-analysis were designed to analyze the current literature on these two procedures in their treatment of delayed and non-union femur fractures to determine their overall efficacy and factors related to their success.

MEDLINE and OVID search databases were used to identify relevant, peer-reviewed articles published within scientific and medical research journals. The following key words were inputted in different combinations in order to search the field of publications in its entirety: “non-union”, “delayed union”, “ununited”, “femur fracture”, “femoral fracture”, “exchange nailing”, “dynaiz(s)ation”, “secondary nailing”, “dynamic”, “static”, and “nail revision”. The initial search yielded over 150 results, and was refined based on the inclusion criteria: Only studies reporting on humans, non-unions and delayed unions, and the usage of exchange nailing and/or dynamization as a secondary treatment after failed IM nailing. The resulting 66 articles were obtained through online journal access. The results were filtered further based on the exclusion criteria: No articles that failed to report overall union rates, differentiate between success rates of their reported techniques, or articles that analyzed less than 5 patients. In all, 31 articles (including retrospective studies and randomized controlled studies), published between 05/1973 and 12/2015, were included in the study (Figure 1).

Isolation and pooling of dependent variables and summary measures from the 31 papers were completed using set guidelines. Patients treated in each study were required to have previously undergone treatment with an IM nail that was still in place at the time of the secondary surgery being studied. Therefore, implantation of a dynamically locked IM nail following external fixation/plating was considered neither exchange nailing nor dynamization. Dynamization of IM nails were required to be in response to failed progression towards union (delayed/non-union). Patients receiving dynamization as part of their original treatment plan were excluded from the analysis. When analyzing patient demographics, patient information tables included in the studies were the primary source used. Bilateral fractures were recorded as separate fractures with independent characteristics. Additionally, revision surgeries and progression to union were recorded but repeated surgeries were not considered in overall union rates (three exchange nailing procedures to achieve union were considered as a failure of the secondary treatment under investigation to achieve union). Verified infections were recorded and included only when discrete from other patient information, so as to prevent skewing of the overall results. Finally, patients lost to follow-up were excluded from the analysis unless osseous union was confirmed prior to them leaving the study.

In order to analyze the information, all of the demographical information for patients from each surgical procedure was combined and used to compare each demographic category against the overall union rate of its respective surgical procedure as well as against the same category of the opposite surgical procedure. Statistical significance was determined using graphpad™ to run Fischer exact or χ2 tests (based on category sizes) with P-values reported next to statistically significant information. Time to union was analyzed using a two-tail T-test. Significance for all analyses was determined to be P < 0.05.

Exchange nailing showed to be the significantly more effective treatment procedure with an overall union rate of 84.785% compared to 66.412% in dynamization (P < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in the average time to osseous union following either surgical procedure (4.769 ± 1.986 mo dynamization, 5.193 ± 2.310 mo exchange nailing, P = 0.3622). Therefore, the overall difference found while comparing the two procedures was their successful union rates (Table 1).

| Surgical procedure | Surgical subtype | No. of articles reporting on secondary procedure (patient number) | Average union % | Average reported time to union |

| Dynamization | All | 7 (131) | 66.412b | 4.769 ± 1.986 mo (26 pts)a |

| Exchange nailing | All | 26 (644) | 84.785b | 5.193 ± 2.310 mo (372 pts)a |

| Exchange nailing | Static locking | 15 (235 pts) | 84.259 | 5.149 ± 2.366 mo (103 pts) |

| Exchange nailing | Dynamic locking | 13 (211 pts) | 82.381 | 5.208 ± 2.475 mo (84 pts) |

Dynamically locking exchange nails resulted in an average union time of 5.208 ± 2.475 mo compared to 5.149 ± 2.366 (P = 0.8682) in statically locked exchange nails. The overall union rate of the two procedures, statically and dynamically locked exchange nailing yielded union rates of 84.259% and 82.381% respectively. Therefore, there was no significant difference between the different locking methods of exchange nailing for union rate or time to union at a significance value of P < 0.05 (Table 1).

Union rates of specific demographics were compared across procedures and compared against each procedure’s overall union rates. Several demographics in exchange nailing yielded significantly different overall rates of union compared to exchange nailing as a whole. Of these demographics, tobacco use (54/74, P = 0.0023), infra and supra-isthmal fracture location (5/9, P = 0.0265, 10/16, P = 0.0045) and infection (19/30, P = 0.0019) were shown to have a significant negative impact on the outcome of exchange nailing (Tables 2-5). The isthmal classification system yielded significantly lower union rates compared to the overall rates of exchange nailing while proximal, middle, and distal thirds categories did not yield a difference. Therefore, in comparison, the isthmal classification system appears to be more useful for predicting surgical outcomes based on fracture location. However, a larger patient pool would be preferable to confirm these results.

| Exchange nailing | Dynamization | EN vs dynam | |||

| Union/total reported | Significant vs total union rate | Union/total reported | Significant vs total union rate | P-values | |

| No. of patients | 556/644 | - | 84/131 | - | P < 0.0001 |

| Ages | |||||

| Mean | 38.002 | - | 32.234 | - | - |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 244/284 | NS | 37/66 | NS | P < 0.0001 |

| Female | 72/86 | NS | 17/26 | NS | NS |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| Yes | 54/74 | P = 0.0023 | 2/3 | NS | NS |

| No | 49/62 | NS | 0/3 | P = 0.0500 | P = 0.0128 |

| NSAIDs use | |||||

| Yes | 4/8 | P = 0.0166 | 0/0 | - | - |

| No | 38/52 | P = 0.0093 | 2/6 | NS | P = 0.0463 |

| Diabetic | |||||

| Yes | 0/0 | - | 0/0 | - | - |

| No | 10/19 | P = 0.0006 | 0/0 | - | - |

| IDDM (type 1) | 0/0 | - | 0/0 | - | - |

| Exchange nailing | Dynamization | EN vs dynam | |||

| Union/total reported | Significant vs total union rate | Union/total reported | Significant vs total union rate | P-values | |

| No. of patients | 556/644 | - | 84/131 | - | P < 0.0001 |

| Mechanism of injury | |||||

| Crush | 2/2 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Gun shot wound | 2/2 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Motorcycle Accident | 27/35 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Pedestrain/bike vs motor vehicle | 2/6 | P = 0.0045 | 0/0 | - | - |

| Motor vehicle accident | 146/163 | NS | 14/24 | NS | P = 0.0004 |

| Fall | 1/5 | P = 0.0017 | 0/0 | - | - |

| Sporting accident | 1/1 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Industrial accident | 2/3 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Non-traumatic | 0/0 | - | 0/0 | - | - |

| Bombing injury | 0/0 | - | 0/0 | - | - |

| Location of injury | |||||

| Proximal shaft | 26/30 | NS | 2/3 | NS | NS |

| Mid-shaft/isthmal | 139/154 | NS | 32/51 | NS | P < 0.0001 |

| Distal shaft | 38/43 | NS | 1/3 | NS | NS |

| Supra-isthmal | 10/16 | P = 0.0172 | 1/1 | NS | NS |

| Sub-trochanteric | 4/4 | NS | 2/3 | NS | NS |

| Infra-isthmal | 5/9 | P = 0.0265 | 0/0 | - | - |

| Fracture pattern | |||||

| Oblique | 21/21 | NS | 0/0 | NS | - |

| Segmental | 0/0 | - | 2/5 | NS | - |

| Transverse | 14/14 | NS | 0/0 | NS | - |

| Commimuted | 19/21 | NS | 17/30 | NS | P = 0.0219 |

| Open vs closed | |||||

| Closed | 133/162 | NS | 14/24 | NS | P < 0.0001 |

| Opened | 25/32 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| I | 1/2 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| II | 2/4 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| IIIA | 1/2 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| IIIB/C | 1/1 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Winquist-Hansen classification | |||||

| Stable | 41/64 | P < 0.0001 | 20/29 | NS | NS |

| O | 7/13 | P = 0.0054 | 0/0 | - | - |

| I | 18/23 | NS | 12/17 | NS | NS |

| II | 16/27 | P = 0.0007 | 6/9 | NS | NS |

| Unstable | 14/23 | P = 0.0028 | 22/36 | NS | NS |

| III | 11/17 | P = 0.0234 | 6/9 | NS | NS |

| IV | 3/6 | P = 0.0387 | 2/2 | NS | NS |

| V | 0/0 | - | 2/2 | NS | - |

| Presence of fracture graph | |||||

| Present | 0/0 | - | 29/44 | NS | - |

| No gap | 0/0 | - | 1/1 | NS | - |

| Exchange nailing | Dynamization | EN vs dynam | |||

| Union/total reported | Significant vs total union rate | Union/total reported | Significant vs total union rate | P-values | |

| No. of patients | 556/644 | - | 84/131 | - | P < 0.0001 |

| Reamed vs unreamed | |||||

| Reamed | 516/598 | NS | NA | - | - |

| Unreamed | 19/22 | NS | NA | - | - |

| Static vs dynamic | |||||

| Dynamic | 97/115 | NS | NA | - | - |

| Static | 173/210 | NS | NA | - | - |

| No locking (/Kuntschner) | 35/36 | NS | NA | - | - |

| Delayed union | 25/27 | NS | 45/55 | P = 0.0228 | P = 0.3199 |

| Nonunion (+type) | 491/567 | NS | 24/57 | P = 0.0063 | P < 0.0001 |

| Elephant | 6/7 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Horse | 12/18 | P = 0.0310 | 0/0 | - | - |

| Oligotrophic | 22/22 | NS | 16/22 | NS | P = 0.0211 |

| Hypotrophic | 9/13 | NS | 0/0 | - | - |

| Atrophic | 80/99 | NS | 5/12 | NS | P = 0.0064 |

| Hypertrophic | 72/83 | NS | 9/11 | NS | NS |

| Bone grafting used | |||||

| Yes | 98/106 | NS | 2/2 | NS | NS |

| No | 165/190 | NS | 32/53 | NS | P < 0.0001 |

| Infected | 19/30 | P = 0.0019 | 0/0 | - | - |

| Patients lost to follow-up | 28 | - | 4 | - | - |

| Major complications following surgery | 45 | - | 13 | - | NS |

| Patients achieving union after additional surgery vs surgeries attempted | 82/92 | - | 34/34 | - | - |

| PMID | Procedure(s) analyzed | Union rate (%) |

| 21726859 | Dynamization | 33.333 |

| 9462352 | Dynamization | 41.667 |

| 8370009 | Dynamization | 45.455 |

| 9291371 | Dynamization | 58.33 |

| 22841533 | Dynamization | 71.795 |

| 12142827 | Dynamization | 78.947 |

| 10088839 | Dynamization | 90 |

| 20101132 | Exchange nailing | 28.571 |

| 10926240 | Exchange nailing | 55.56 |

| 12719163 | Exchange nailing | 57.895 |

| 24978947 | Exchange nailing | 69.444 |

| 6488644 | Exchange nailing | 75 |

| 26489394 | Exchange nailing | 75.676 |

| 22327999 | Exchange nailing | 78.049 |

| 10791668 | Exchange nailing | 78.26 |

| 1738973 | Exchange nailing | 81.25 |

| 25300373 | Exchange nailing | 81.966 |

| 19897987 | Exchange nailing | 85.714 |

| 22338431 | Exchange nailing | 90.698 |

| 18579143 | Exchange nailing | 90.909 |

| 12142827 | Exchange nailing | 90.909 |

| 12479620 | Exchange nailing | 91.667 |

| 18090018 | Exchange nailing | 91.892 |

| 10476292 | Exchange nailing | 96 |

| 4707299 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| 10088839 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| 20820792 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| Kim JR1 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| 9253919 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| 10513972 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| 1126078 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| 7965294 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

| 22009873 | Exchange nailing | 100 |

Of the dynamization factors, union rates of delayed union (45/55, P = 0.0228) and non-union fractures (24/57, P < 0.0063) were significantly better and worse, respectively, in comparison to dynamization’s overall union rate (84/131) (Table 4). Dynamization of delayed unions proved to be a more successful procedure than dynamization of non-unions in femurs. When comparing demographics across surgical procedures, there was a lack of a statistical difference between female patients (72/86 EN and 17/26 dynam, P = 0.0544), hypertrophic fractures (72/83 EN and 9/11 dynam, P = 0.6563), and delayed union (25/27 EN and 45/55 dynam, P = 0.3199) (Table 2 and 4)

The analysis showed exchange nailing to be the more successful choice in the treatment of femoral non-unions in respect to its higher success rate (491/567 EN, 24/57 dynam, P < 0.0001). However, there was no significant difference between the success rates of the two procedures for delayed union fractures (25/27 EN, 45/55 dynam, P = 0.3299). Without a clear preference in overall success rates for one procedure over the other, additional surgical factors were examined. Dynamization, in comparison to exchange nailing, is a significantly less invasive procedure, has a lower financial cost, and comparable complication rates[1] (Table 4). With these factors in mind, in addition to the comparable success rates, the overall results suggest dynamization as the treatment of choice in patients with delayed union femur fractures.

On the other hand, exchange nailing showed a significantly higher success rate in non-unions when compared to dynamization (491/567 EN, 24/57 dynam, P < 0.001). In order to avoid the need for further surgical interventions, exchange nailing should be the first consideration in the treatment of non-union femur fractures. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the success rates or time to union between static and dynamic locking modes of exchange nailing (Table 1). When performing exchange nailing, clinicians should look to alternate factors specific to each patient when deciding which locking method to use in their treatment plans.

While exchange nailing and dynamization have been used as revision techniques for decades, the overall efficacy of each procedure is currently disputed[6-36]. Multiple factors and varying rates of success were published in the field with little consistency between papers. The current study examines the literature, utilizing a large subject pool of all published information in the field regarding these procedures.

Several previous authors raised concern for the use of a distal vs mid vs proximal fracture classification when considering treatments in favor of the infra, supra, sub, and isthmal classification[16]. The current analysis lent favor to their speculation in favor of the isthmal classification system (Table 3). Additionally, some authors even went on to propose different algorithms for the proper treatment of non-unions based of fracture characteristics, including fracture stability[36]. Following the analysis, the differences found between the individual isthmal classifications lend favor to its use over other systems.

In addition to fracture location, authors have raised questions over other factors that may affect procedural outcomes. While over-reaming is considered standard in most exchange nailing procedures, the suggested amount varies. Some articles report significant increase in union rates with different reaming sizes, while others found no difference. There was difficulty in comparing these claims across the literature due to the variation in reporting. Of the authors reporting reaming sizes, different ranges in millimeters (i.e., 1 mm, 2 mm, 3 mm vs 0-1 mm, 2-4 mm) were typically used disallowing consolidation of the information.

Authors additionally raised concern over the success rates of exchange nailing based on the anterograde or retrograde revision technique[17], as well as the open or closed techniques[29]. Wu et al[29] found the closed revision technique of exchange nailing lead to faster union times while requiring less operating time to complete the procedure. However, they found the overall union rates of the procedures to be identical at 100%. In the other study, Wu et al[17] investigated the use of retrograde dynamic nailing after antegrade locked nailing had failed. In all 13 patients, retrograde revision techniques lead to osseous union of the femur fracture. Information in additional articles addressing these procedural techniques was not found leaving their comparisons for future research to address.

While a large amount of patient information regarding these secondary treatments was gathered, the analysis was limited by the variation in reporting and characteristic descriptions across all papers. Some papers lacked specific patient information in regard to procedure successes and failures, while others reported characteristics in ways that hindered consolidation of the data. As such, the total patient population was restricted. In order to provide a more representative review of entire field of research, increased patient numbers and more consistent reporting styles are needed.

Future analysis of these procedures should be performed once more data has been published. While the analysis yielded some significant results, other patient characteristics need to be investigated more thoroughly to gain a comprehensive insight into the common factors influencing procedure outcomes. Additionally, a comparison of external fixation/plating and internal fixation procedures in femoral non-unions could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the situations that require each secondary treatment technique.

While exchange nailing showed higher union rates with comparable healing times to dynamization overall and in non-unions, the two procedures showed no significant difference in their results for the treatment of delayed unions. Upon examination of additional factors, specifically cost and invasiveness, dynamization should be considered the first treatment of delayed femur fractures. Conversely, in order to avoid further complications, including the need for additional surgery, exchange nailing is the treatment of choice for non-unions.

Dynamization involves the removal of proximal or distal locking screws in a statically locked IM nail which allowing weight bearing to stimulate osseous growth at the fracture site.

Although rare, delayed union and non-union of fractures are major complications in the treatment of femoral fractures with intramedullary (IM) nailing. Surgeons use dynamization and exchange nailing to treat these complications and achieve osseous union.

The purpose of this study is to analyze the literature on these procedures in their treatment of delayed and non-union femur fractures to determine their efficacy and factors related to their success.

Exchange nailing consists of the removal of the current IM nail, debridement of the medullary cavity, followed by insertion of a larger IM nail. Currently there is lack updated systematic review and meta-analysis on efficacy of dynamamization vs exchange nailing in treatment of delayed and non-union femur fractures.

Ultimately, 31 peer-reviewed articles with 644 exchanged nailing patients and 131 dynamization patients were identified and analyzed. It was found that when treating femoral non-unions, exchange nailing was shown to achieve osseous union in a higher percentage of patients than dynamization with comparable recovery times. However, dynamization appears to be equally as effective as exchange nailing in the treatment of delayed unions.

Exchange nailing is the procedure of choice between the two in the treatment of femoral non-unions due to its significantly higher success rate.

Clinical randomized controlled studies on this topic will help further elucidate this conclusion.

We thank the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences’ Medical Student Summer Research Program for allowing collaboration between students and faculty, making this research project possible.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Drampalos E, Emara KM S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Vaughn J, Gotha H, Cohen E, Fantry AJ, Feller RJ, Van Meter J, Hayda R, Born CT. Nail Dynamization for Delayed Union and Nonunion in Femur and Tibia Fractures. Orthopedics. 2016;39:e1117-e1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lynch JR, Taitsman LA, Barei DP, Nork SE. Femoral nonunion: risk factors and treatment options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:88-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tigani D, Fravisini M, Stagni C, Pascarella R, Boriani S. Interlocking nail for femoral shaft fractures: is dynamization always necessary? Int Orthop. 2005;29:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gelalis ID, Politis AN, Arnaoutoglou CM, Korompilias AV, Pakos EE, Vekris MD, Karageorgos A, Xenakis TA. Diagnostic and tr–eatment modalities in nonunions of the femoral shaft: a review. Injury. 2012;43:980-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brinker MR, O’Connor DP. Exchange nailing of ununited fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huang KC, Tong KM, Lin YM, Loh el-W, Hsu CE. Evaluation of methods and timing in nail dynamisation for treating delayed healing femoral shaft fractures. Injury. 2012;43:1747-1752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Papakostidis C, Psyllakis I, Vardakas D, Grestas A, Giannoudis PV. Femoral-shaft fractures and nonunions treated with intramedullary nails: the role of dynamisation. Injury. 2011;42:1353-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pihlajamäki HK, Salminen ST, Böstman OM. The treatment of nonunions following intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:394-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wolinsky PR, McCarty E, Shyr Y, Johnson K. Reamed intramedullary nailing of the femur: 551 cases. J Trauma. 1999;46:392-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wu CC, Chen WJ. Healing of 56 segmental femoral shaft fractures after locked nailing. Poor results of dynamization. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:537-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu CC. The effect of dynamization on slowing the healing of femur shaft fractures after interlocking nailing. J Trauma. 1997;43:263-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu CC, Shih CH. Effect of dynamization of a static interlocking nail on fracture healing. Can J Surg. 1993;36:302-306. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Tsang ST, Mills LA, Baren J, Frantzias J, Keating JF, Simpson AH. Exchange nailing for femoral diaphyseal fracture non-unions: Risk factors for failure. Injury. 2015;46:2404-2409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hierholzer C, Glowalla C, Herrler M, von Rüden C, Hungerer S, Bühren V, Friederichs J. Reamed intramedullary exchange nailing: treatment of choice of aseptic femoral shaft nonunion. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Swanson EA, Garrard EC, Bernstein DT, O Connor DP, Brinker MR. Results of a systematic approach to exchange nailing for the treatment of aseptic femoral nonunions. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang KH, Kim JR, Park J. Nonisthmal femoral shaft nonunion as a risk factor for exchange nailing failure. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:E60-E64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu CC. Retrograde dynamic locked nailing for aseptic nonunion of femoral supracondyle after antegrade locked nailing. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:513-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Naeem-ur-Razaq M, Qasim M, Sultan S. Exchange nailing for non-union of femoral shaft fractures. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2010;22:106-109. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Park J, Kim SG, Yoon HK, Yang KH. The treatment of nonisthmal femoral shaft nonunions with im nail exchange versus augmentation plating. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shroeder JE, Mosheiff R, Khoury A, Liebergall M, Weil YA. The outcome of closed, intramedullary exchange nailing with reamed insertion in the treatment of femoral shaft nonunions. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:653-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gao KD, Huang JH, Li F, Wang QG, Li HQ, Tao J, Wang JD, Wu XM, Wu XF, Zhou ZH. Treatment of aseptic diaphyseal nonunion of the lower extremities with exchange intramedullary nailing and blocking screws without open bone graft. Orthop Surg. 2009;1:264-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Oh JK, Bae JH, Oh CW, Biswal S, Hur CR. Treatment of femoral and tibial diaphyseal nonunions using reamed intramedullary nailing without bone graft. Injury. 2008;39:952-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu CC. Exchange nailing for aseptic nonunion of femoral shaft: a retrospective cohort study for effect of reaming size. J Trauma. 2007;63:859-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Banaszkiewicz PA, Sabboubeh A, McLeod I, Maffulli N. Femoral exchange nailing for aseptic non-union: not the end to all problems. Injury. 2003;34:349-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yu CW, Wu CC, Chen WJ. Aseptic nonunion of a femoral shaft treated using exchange nailing. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25:591-598. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Wu CC, Shih CH. Treatment of 84 cases of femoral nonunion. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:57-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Weresh MJ, Hakanson R, Stover MD, Sims SH, Kellam JF, Bosse MJ. Failure of exchange reamed intramedullary nails for ununited femoral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:335-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hak DJ, Lee SS, Goulet JA. Success of exchange reamed intramedullary nailing for femoral shaft nonunion or delayed union. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:178-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wu CC, Shih CH, Chen WJ, Tai CL. Treatment of ununited femoral shaft fractures associated with locked nail breakage: comparison between closed and open revision techniques. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13:494-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Oh I, Nahigian SH, Rascher JJ, Farrall JP. Closed intramedullary nailing for ununited femoral shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;106:206-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wu CC, Chen WJ. Treatment of femoral shaft aseptic nonunions: comparison between closed and open bone-grafting techniques. J Trauma. 1997;43:112-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Christensen NO. Küntscher intramedullary reaming and nail fixation for non-union of fracture of the femur and the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1973;55:312-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Harper MC. Ununited fractures of the femur stabilized with the fluted rod. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;190:273-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Iannacone WM, Bennett FS, DeLong WG Jr, Born CT, Dalsey RM. Initial experience with the treatment of supracondylar femoral fractures using the supracondylar intramedullary nail: a preliminary report. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Furlong AJ, Giannoudis PV, DeBoer P, Matthews SJ, MacDonald DA, Smith RM. Exchange nailing for femoral shaft aseptic non-union. Injury. 1999;30:245-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kim JR, Chung WC, Shin SJ, Seo KB. The management of aseptic nonunion of femoral shaft fractures after interlocking intramedullary nailing. Eur J Orthop Surg Tr Name. 2011;21:171-177. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |