Published online Jul 18, 2017. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i7.536

Peer-review started: November 23, 2016

First decision: February 15, 2017

Revised: April 17, 2017

Accepted: May 3, 2017

Article in press: May 5, 2017

Published online: July 18, 2017

Processing time: 235 Days and 12.6 Hours

To investigate if there are typical degenerative changes in the ageing sternoclavicular joint (SCJ), potentially accessible for arthroscopic intervention.

Both SCJs were obtained from 39 human cadavers (mean age: 79 years, range: 59-96, 13 F/26 M). Each frozen specimen was divided frontally with a band saw, so that both SCJs were opened in the same section through the center of the discs. After thawing of the specimens, the condition of the discs was evaluated by probing and visual inspection. The articular cartilages were graded according to Outerbridge, and disc attachments were probed. Cranio-caudal heights of the joint cartilages were measured. Superior motion of the clavicle with inferior movement of the lateral clavicle was measured.

Degenerative changes of the discs were common. Only 22 discs (28%) were fully attached and the discs were thickest superiorly. We found a typical pattern: Detachment of the disc inferiorly in connection with thinning, fraying and fragmentation of the inferior part of the disc, and detachment from the anterior and/or posterior capsule. Severe joint cartilage degeneration ≥ grade 3 was more common on the clavicular side (73%) than on the sternal side (54%) of the joint. In cadavers < 70 years 75% had ≤ grade 2 changes while this was the case for only 19% aged 90 years or more. There was no difference in cartilage changes when right and left sides were compared, and no difference between sexes. Only one cadaver - a woman aged 60 years - had normal cartilages.

Changes in the disc and cartilages can be treated by resection of disc, cartilage, intraarticular osteophytes or medial clavicle end. Reattachment of a degenerated disc is not possible.

Core tip: Arthroscopic treatment is an option in patients with symptoms from the ageing sternoclavicular joint (SCJ). However, knowledge of age-related changes is essential for planning of such arthroscopic procedures. In 78 human cadaveric SCJs with a mean age of 79 years (range: 59-96 years) we found that degenerative changes of the discs were common, in particular inferior detachment, and only 28% were fully attached. Severe cartilage degeneration was more common on the clavicular than the sternal side. When there was inferior detachment of the disc, we observed increased supero-medial gliding of the clavicle. We conclude that a torn disc or degenerated articular cartilage might be treated by arthroscopic resection, debridement and clavicle end resection. Reattachment of a degenerated disc is not possible.

- Citation: Rathcke M, Tranum-Jensen J, Krogsgaard MR. Possibilities for arthroscopic treatment of the ageing sternoclavicular joint. World J Orthop 2017; 8(7): 536-544

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v8/i7/536.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v8.i7.536

Arthroscopy has opened for specific procedures on the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ), e.g., resection of a torn intraarticular disc. Changes of the joint with age might be expected just like it is seen in the acromioclavicular joint, due to the substantial gliding and rotation in both joints during movement of the arm[1-3]. Resection of the lateral clavicle end is a common procedure for painful osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular joint. The prevalence of symptoms from SCJ is unknown, but surgery on the joint is infrequent[4-6], partly by tradition and perhaps of fear to injure vessels and lungs adjacent to its posterior capsule[7].

Open resection of the articular disc and capsulorrhaphy in patients with degenerative disease of the SCJ has been reported successful in 6 patients[8]. Open resection of the medial clavicular end show good results in treatment for SCJ osteoarthritis[9,10] when the costoclavicular ligament is kept intact[10-12]. However, the scar after open surgery can be cosmetically prominent because of the location.

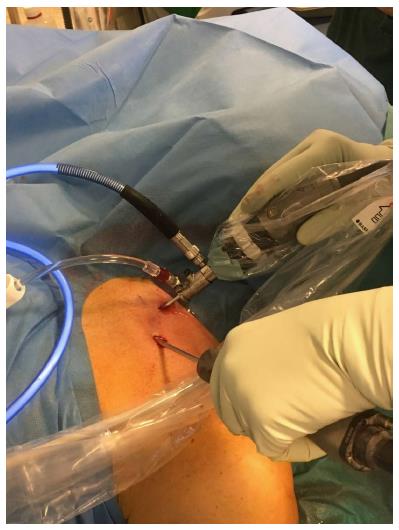

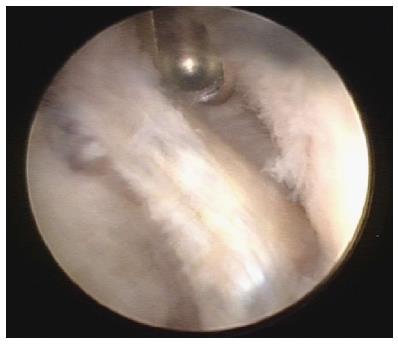

Arthroscopic surgery of the SCJ can be performed through two portals (Figure 1), leaving minor scars, using a 2.7 mm arthroscope and standard instruments (Figure 2). The two portals give access to both compartments of the joint on either side of the articular disc. The depth of the joint is about 1.5 cm, and care should be taken not to exceed this during introduction of the arthroscope, in order not to penetrate the posterior capsule. Once the arthroscope is introduced all structures are usually easy to identify, and resection of the disc, medial clavicle or intraarticular osteophytes, as well as synovectomy and removal of loose bodies can be performed under visual control without risk of penetrating into the mediastinum.

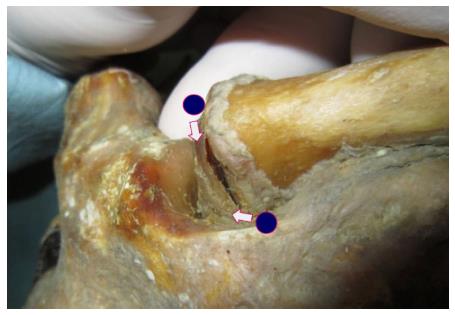

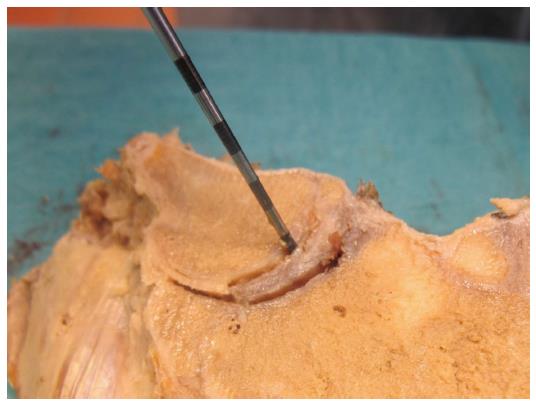

The articular disc of SCJ is superiorly attached to the medial end of the clavicle, inferiorly to the first rib at its junction with the manubrium and to the joint capsule. In older cadavers the disc is incomplete in 29%-56%[13-16], with a central hole[13,15,16] or a meniscoid appearance[14]. During arthroscopy in younger patients (age mean 40 years, range: 16-70, 28 F/11 M) we have often found detachment of the disc from the anterior capsule and marked disintegration of the disc at the inferior part with detachment from manubrium (Figure 3) (unpublished).

These differences in reported changes are confusing in relation to whether there is an anatomic basis for arthroscopic treatment of the disc in the painful ageing SCJ.

Degenerative changes of the articular cartilage are reported to be more severe on the medial clavicle compared to manubrium[16], which is surprising as the superior part of the clavicular cartilage only articulates when the arm is abducted.

Our aims were to study the anatomy of the SCJ, focusing on the occurrence of conditions that are potentially accessible for surgical intervention. Also, to evaluate if the hyaline cartilages on the clavicle and manubrium are equally affected by age, and if degenerative conditions and detachment of the disc has any influence on medial end clavicular stability.

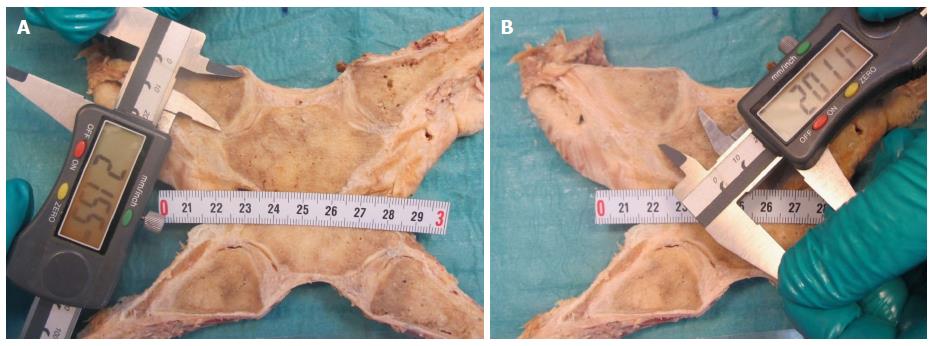

From 39 formalin embalmed human cadavers (age mean: 79 years, range: 59-96, 13 F/26 M) we obtained both SCJs. The sternum was cut at level of the second rib, and clavicles and first rib were cut lateral to the costoclavicular ligament. To be able to examine the capsular attachments of the intraarticular disc, each specimen was frozen and divided frontally with a thin band saw, so that both SCJs were opened in the same section through the center of the disc (Figure 4). Examination of the joints was performed after the specimens had been thawed and stored in 30% ethanol. The cut surfaces were cleaned with a dry cloth. The height of the articular cartilage (cranio-caudal) on the clavicle and manubrium was measured (Figure 5). The attachments of the intraarticular disc to the clavicle and first rib-manubrium junction as well as to the anterior and posterior capsule were probed with a hooked arthroscopic probe (Figure 6). Any detachment was recorded. The disc was probed, and holes, fraying and flap lesions were visually inspected and recorded. The thickest and thinnest parts of the disc were measured with a calipergauge designed especially for this purpose (Figure 7). The cartilage at the medial clavicular end and at manubrium was classified according to Outerbridge[17] based on visual inspection and probing, and by agreement of two observers. Information about the age and sex of the cadavers was obtained after the measurements had been recorded. There were no signs of previous surgery to any of the SCJs.

The study was conducted on deceased who had bequeathed their bodies to science and education at the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine (ICMM) at the University of Copenhagen according to Danish legislation (Health Law #546, § 188). The study was approved by the head of the body donation program at ICMM. The study was performed at Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine (ICMM), University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The data are presented as mean ± SD. For the statistics, Student’s t test was used. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

In the 26 males 4 discs were missing on the right side, 1 joint was ankylotic and 21 discs were present, but 4 of these had a central hole. On the left side 4 discs were missing, 22 were present and 3 of these had a central hole.

In the 13 females 3 discs were missing on the right side, 10 were present and 4 of these had a central hole. On the left side 2 discs were missing, 11 were present and 4 of these had a central hole.

Figure 8 visualizes the attachments of the discs, illustrating that the discs were most often detached inferiorly. Only 22 discs (28%) were fully attached.

In nearly all cases the disc was thickest superiorly. All but one cadaver - a woman aged 60 years - showed degenerative changes of the cartilages. Grade 5 changes (no cartilage) were not seen in any of the specimens, but one joint was ankylotic (no joint cavity). Severe degeneration ≥ grade 3 was seen in 73% on the clavicular side and 54% on the sternal side, confirming that degenerative changes are more common on the clavicular side of the joint. In cadavers < 70 years 75% had ≤ grade 2 changes, while this was the case for only 19% aged 90 years or more. In the age groups 70-79 and 80-89 years 33%-35% had ≤ grade 2 changes. There was no difference in cartilage changes when right and left sides were compared, and no difference between sexes (P > 0.05).

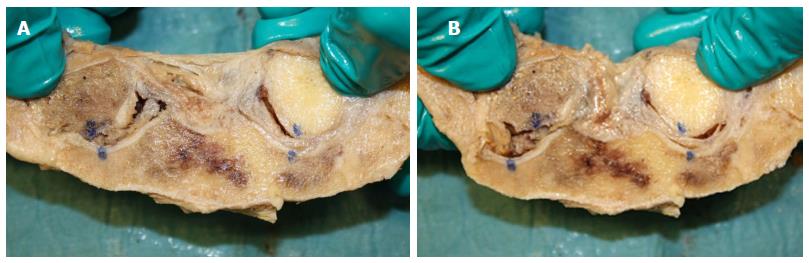

We found a typical pattern: Detachment of the disc inferiorly with thinning, fraying and fragmentation of the inferior part of the disc, and detachment from the anterior and/or posterior capsule. Typical examples of changes in the discs are shown in Figure 9.

In the cases with inferior detachment we found a marked increase in supero-medial displacement of the medial clavicular end compared to cases with intact inferior attachment, when a light medially directed push was applied to the lateral clavicle shaft (P < 0.05) (Figure 9).

The mean cranio-caudal length ± 1 SD of the joint cartilages was in male cadavers on the right side 26.0 ± 3.1 mm on the clavicle and 18.1 ± 2.0 mm on the sternum, and on the left side 25.4 ± 2.9 mm and 17.9 ± 2.3 mm, respectively, while in female cadavers on the right side it was 23.5 ± 2.9 mm on the clavicle and 17.2 ± 1.7 mm on the sternum, and on the left side 24.1 ± 3.0 mm and 17.5 ± 2.1 mm, respectively. All data are shown in Table 1.

| Age (yr) | Sex | Right thinnest/thickest part of disc mm1 | Left thinnest/thickest part of disc mm1 | Right attach-ment disc2 | Left attach-ment disc2 | Right cartilage C/S mm | Left cartilage C/S mm | Right cartilage quality C/S3 | Left cartilage quality C/S3 |

| 59 | F | 2.1 i/3.1 s | 2.2 i/4.4 s | 1 | 5 | 21/15 | 22/14 | 2/2 | 3/3 |

| 60 | F | 0 i/3.9 s | 0.5 i/3.9 s | 5 | 1 | 23/18 | 25/20 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 65 | M | 2.3 i/4.3 s | 4.4 i/6.4 s | 1 | 1 | 24/17 | 26/17 | 2/1 | 2/1 |

| 65 | F | 1.7 i/4.8 s | 0/2.4 | 1 | 5 | 27/18 | 24/21 | 1/1 | 4/4 |

| 66 | M | 2.2 i/4.3 s | 0.9 i/4.2 s | 5 | 1 | 30/19 | 26/21 | 1/1 | 3/1 |

| 71 | M | 1.2 i/4.5 s | 2.2 i/6.3 s | 4 + 5 | 1 | 32/20 | 29/21 | 3/2 | 2/3 |

| 71 | M | 0.6 i/1.6 s | 0.9 i/2.2 s | 3 | 5 | 21/17 | 22/13 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| 72 | F | 0 i/1.4 s | 0 c/2.6 s | 2 + 5 | 1 | 25/18 | 26/19 | 3/2 | 3/2 |

| 73 | M | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | 31/20 | 29/21 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| 73 | M | 0/3.2 anterior rim | 0/4.0 anterior rim | 3 + 4 + 5 | 3 + 4 + 5 | 28/18 | 24/17 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| 74 | M | 2.9 i/3.8 s | 2.0 s/3.3 i | 2 + 4 + 5 | 1 | 29/19 | 28/17 | 3/2 | 3/2 |

| 75 | F | Absent | 2.1 i/2.8 s | Absent | 5 | 19/15 | 18/14 | 3/2 | 1/1 |

| 75 | M | 2.5 i/3.5 s | 1.1 i/4.1 s | 5 | 1 | 25/14 | 25/18 | 3/3 | 2/3 |

| 76 | M | 0/2.2 i (flap) | 2.3 i + s/3.8 c | 3 + 4 | 1 | 27/17 | 25/17 | 4/4 | 2/3 |

| 78 | M | 3.5 i/4.5 s | 3.5 i/5.7 s | 3 | 1 | 27/19 | 25/22 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| 78 | M | 2.3 i/3.0 s | 1.0 i/2.9 s | 5 | 5 | 26/17 | 27/18 | 2/1 | 2/1 |

| 78 | M | Absent | 0.9 i/3.4 s | Absent | 1 | 25/17 | 29/19 | 4/4 | 3/3 |

| 79 | M | 0 i/0.8 s | 0/2.7 s | 5 | 5 | 21/17 | 21/17 | 2/3 | 3/2 |

| 79 | M | 2.0 i/3.7 s | Absent | 5 | Absent | 29/21 | 28/20 | 3/3 | 2/2 |

| 79 | M | 0.5 i/3.9 s | 0.1 i/4.4 s | 1 | 1 | 24/16 | 21/16 | 3/2 | 4/2 |

| 79 | M | Ankylosis | 2.0 i/5.2 s | Ankylosis | 4 + 5 | 25/20 | 23/16 | Ankylosis | 3/3 |

| 81 | F | 1.8 i/3.3 s | 0/2.9 s | 5 | 4 + 5 | 24/17 | 25/17 | 2/1 | 1/1 |

| 81 | F | Absent | 1.2 s/2.7 i | Absent | 3 | 26/20 | 28/19 | 4/4 | 3/2 |

| 83 | M | 1.0 s/2.9 i | 3.0 i/3.6 s | 5 | 5 | 28/21 | 24/13 | 4/3 | 4/2 |

| 84 | M | 2.3 i/5.4 s | 3.0 i/4.9 s | 5 | 1 | 26/20 | 26/19 | 3/1 | 2/1 |

| 84 | M | 1.0 i/1.7 s | 1.6 s/1.4 i | 1 | 1 | 24/16 | 24/19 | 3/1 | 3/1 |

| 84 | M | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | 23/20 | 24/19 | 3/4 | 3/3 |

| 85 | M | 2.4 i/2.7 s | 1.2 i/3.5 s | 3 + 4 + 5 | 1 | 22/17 | 21/16 | 4/2 | 4/2 |

| 85 | F | 2.3 i/4.0 s | 0/2.2 anterior rim | 5 | 3 + 4 + 5 | 25/18 | 24/17 | 4/2 | 3/3 |

| 86 | F | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | 20/16 | 20/16 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| 89 | F | 1.0 i/2.7 s | Absent | 2 + 5 | Absent | 22/15 | 23/16 | 1/1 | 3/3 |

| 90 | F | 0.8 i/2.5 s | 1.1 s/1.2 i | 1 | 1 | 29/19 | 29/21 | 3/3 | 2/2 |

| 90 | M | 3.3 i/3.6 s | 2.5 i/2.9 s | 4 + 5 | 5 | 26/18 | 28/18 | 4/3 | 4/3 |

| 90 | F | 0/1.9 anterior rim | 1.5 i/2.5 s | 3 + 4 + 5 | 5 | 23/19 | 23/17 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| 91 | F | 0 c/3.1 s | 1.5 i/0 s | 1 | 4 | 21/16 | 26/18 | 4/3 | 4/3 |

| 92 | M | Absent | 1.9 s/3.4 i | 2 + 4 + 5 | 5 | 21/14 | 20/16 | 3/4 | 2/2 |

| 93 | M | 0/0 (absent) | 0/3.2 s | Absent | 4 + 5 | 31/18 | 31/17 | 3/3 | 4/4 |

| 94 | M | 1.7 i/3.3 s | Absent | 2 + 5 | Absent | 26/21 | 27/21 | 3/2 | 4/4 |

| 96 | M | 0/2.2 anterior rim | 0/3.8 anterior rim | 3 + 4 + 5 | 3 + 4 + 5 | 26/18 | 28/17 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

Our main purpose was to evaluate if changes to the intraarticular disc in the ageing SCJ could explain painful mechanical symptoms that are seen in some patients. In light of previous reports we were surprised by the marked changes of the discs observed in the majority of the SCJs. In a large cadaver study[16] 56% of discs were found to be incomplete, but the defects were described as a central hole and fraying. In our study the changes were much more general; in particular inferior detachment was a common finding (20/39 right, 16/39 left). This pattern resembles what we have seen in arthroscopic examination of the SCJ in symptomatic patients with degenerative joint disease. An inferiorly detached disc is more likely to produce mechanical symptoms than a central hole as it is unstable and may cause locking during motion of the joint.

We have no information about symptoms, work or sports activity for the donors. Based on the increasing pathology with increasing age, it is likely, that the changes in the disc and cartilages are of degenerative nature. In the specimens with complete inferior detachment of the disc there was supero-medial instability of the medial clavicular end. Motion of the clavicle relative to manubrium is during most activities sliding with no compression[2]. When the shoulder is depressed the clavicle acts as a lever arm (ratio about 7:1) with the center of rotation (the fulcrum) at its crossing of the first rib (i.e., the site of the costoclavicular ligament), then the sternal end of the clavicle is lifted forcibly upwards. With increased motion of the clavicle, symptoms from an unstable, degenerated disc and degenerated cartilages are likely to increase. A forceful depression of the shoulder, e.g., during lifting a heavy load, applies a substantial load on the interclavicular ligament[1,15]. It is not known to which extent force is absorbed in the disc during lifting, but the attachment of the disc inferiorly on the manubrium and superiorly on the upper facet of the clavicular joint surface indicates that the disc in this respect may function as a ligament, working in synergy with the interclavicular ligament. Histological examination of the disc has shown the most common collagen fibers to be type I, III and V[18] which are all strong fibrillar collagens, designed to resist force.

Slackness of the interclavicular ligament with age might result in increased tension on the disc during lifting, and, in addition to the compressive forces on the inferior part of the disc during motion, this may be an explanation for the high rate of thinning and detachment of the inferior part of the disc.

In addition, the fact that the cranio-caudal length of the articular surface of the clavicle was about 40% longer than the articular surface on the manubrium, meaning that the upper third of the disc is not subject to compressive or frictional forces in most working situations, may explain why the superior part of the disc is often intact.

It is described that symptomatic SCJs with degenerative changes have an increased size of the clavicular head and a relative anterior subluxation of the clavicle compared to asymptomatic joints[1], but not a superior subluxation. Even though the intraarticular disc in most of these joints must be expected to be severely changed and unable to prevent the clavicular head from superior motion during lifting, the enlargement of the head, related to the degenerative condition, might pull the interclavicular ligament superiorly, resulting in a tightening of the ligament. This could explain why the clavicular head in this situation is not subluxating superiorly during depression of the shoulder[19].

There was an overweight of thinning and detachment of the inferior part of the disc on the right side compared to left and fewer normal discs on the right side. Of danes 91% are right dominant and some activities are performed with more power by the dominant arm. This increases load on the SCJ, its ligaments and the disc, and may cause additional wear on the right SCJ on top of the degenerative wear that is affecting both sides.

We could confirm earlier findings of more severe changes of the cartilage on the clavicle compared to manubrium[16]. Therefore, it makes sense to resect the clavicular and not the sternal part of the joint in case of surgery for osteoarthritis of the SCJ.

Arthroscopic surgery of the SCJ is described in a few series[4-6,20]. Resection of the medial clavicular end is the procedure that has been reported in most of the cases[4,5,20], and in open[10] as well as arthroscopic[4,5,20] series it resulted in marked pain reduction. The indication for this operation is degenerative changes that can be demonstrated by X-rays, MRI or CT-scan. In some cases of pain in the SCJ no such changes can be demonstrated. Our study shows that at least in the elderly population detachment of the articular disc is common. It is not known to which extent these changes in the disc are symptomatic, but detachment can probably lead to pain, locking and swelling, and technically it can be treated by arthroscopic debridement or resection of the disc as well as resection of the medial clavicular end. Pathology of the disc is not visible on X-rays or CT-scan, but can often be demonstrated on T2 weighted MRI-scans (personal experience). Persistent pain, locking and/or swelling of a SCJ without degenerative changes on X-rays or CT-scan might be caused by detachment or fraying of the disc, and an MRI-scan should be considered in these cases. The detachment and thinning of the discs inferiorly as found in our study means that surgical reattachment of the disc is impossible. Contrary, in case of traumatic detachment of otherwise normal discs in younger individuals, reattachment is an option in case of symptoms.

Detachment or destruction of the articular disc in the SCJ is a common finding in the aging population and can result in pain, locking and swelling which might be treated by resection of the torn disc. Degenerative changes of the articular cartilages are more common on the clavicle than on manubrium, and normal cartilage is rarely seen in this age group. Debridement, chondrectomy and medial clavicle resection may be relevant, but reattachment of the disc is not possible because of the marked tissue changes.

We thank Johnny Grant and Lars-Bo Nielsen for preparation of the specimens and Keld Ottosen for preparing the graphic illustration (Figure 8).

Arthroscopy of the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) is a recently introduced technique that has opened for more specific procedures on this joint, e.g., resection or reinsertion of a torn disc, synovectomy, chondrectomy and removal of loose bodies. Knowledge of age-related changes is essential for planning of arthroscopic procedures, and previous cadaver studies have shown conflicting results.

Open surgical procedures on the SCJ leave a scar at a cosmetically problematic location, and visualization of the deep part of the joint is often limited. Arthroscopy makes full inspection of the SCJ possible. The arthroscopic procedure that has previously been reported in the SCJ is clavicle end resection for osteoarthritis.

This is the first study to describe the SCJ in cadaver specimens prepared without interference with the joint capsule and disc attachment sites. The authors found degenerative changes to disc and joint cartilages to be much more common than previously thought and showing in a typical pattern.

Arthroscopic resection of disc, cartilages and clavicular end of the SCJ may be applied in cases of pain, locking or swelling that is resistant to non-surgical intervention.

This is very classic study on degenerative SCJ. The study demonstrated the stage of cartilage in SC comprehensively.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Anand A, Tawonsawatruk T S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Bearn JG. Direct observations on the function of the capsule of the sternoclavicular joint in clavicular support. J Anat. 1967;101:159-170. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ludewig PM, Phadke V, Braman JP, Hassett DR, Cieminski CJ, LaPrade RF. Motion of the shoulder complex during multiplanar humeral elevation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:378-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 527] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Negri JH, Malavolta EA, Assunção JH, Gracitelli ME, Pereira CA, Bolliger Neto R, Croci AT, Ferreira Neto AA. Assessment of the function and resistance of sternoclavicular ligaments: A biomechanical study in cadavers. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100:727-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tytherleigh-Strong GM, Getgood AJ, Griffiths DE. Arthroscopic intra-articular disk excision of the sternoclavicular joint. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1172-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tytherleigh-Strong G, Griffith D. Arthroscopic excision of the sternoclavicular joint for the treatment of sternoclavicular osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1487-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tytherleigh-Strong G. Arthroscopy of the sternoclavicular joint. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2:e141-e145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Van Tongel A, Van Hoof T, Pouliart N, Debeer P, D’Herde K, De Wilde L. Arthroscopy of the sternoclavicular joint: an anatomic evaluation of structures at risk. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aumann U, Brüning W. [Discopathy of the sternoclavicular joint]. Chirurg. 1980;51:722-726. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Pingsmann A, Patsalis T, Michiels I. Resection arthroplasty of the sternoclavicular joint for the treatment of primary degenerative sternoclavicular arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:513-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rockwood CA, Groh GI, Wirth MA, Grassi FA. Resection arthroplasty of the sternoclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Carrera EF, Archetti Neto N, Carvalho RL, Souza MA, Santos JB, Faloppa F. Resection of the medial end of the clavicle: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:112-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee JT, Campbell KJ, Michalski MP, Wilson KJ, Spiegl UJ, Wijdicks CA, Millett PJ. Surgical anatomy of the sternoclavicular joint: a qualitative and quantitative anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barbaix E, Lapierre M, Van Roy P, Clarijs JP. The sternoclavicular joint: variants of the discus articularis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2000;15 Suppl 1:S3-S7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Emura K, Arakawa T, Terashima T, Miki A. Macroscopic and histological observations on the human sternoclavicular joint disc. Anat Sci Int. 2009;84:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Slappey JB, McEvoy WC, Linganna S, Shoja MM, Oakes WJ. Surgical and clinical anatomy of the interclavicular ligament. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29:357-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Tongel A, MacDonald P, Leiter J, Pouliart N, Peeler J. A cadaveric study of the structural anatomy of the sternoclavicular joint. Clin Anat. 2012;25:903-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43-B:752-757. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Shimada K, Takeshige N, Moriyama H, Miyauchi Y, Shimada S, Fujimaki E. Immunohistochemical study of extracellular matrices and elastic fibers in a human sternoclavicular joint. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 1997;74:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Van Tongel A, Valcke J, Piepers I, Verschueren T, De Wilde L. Relationship of the Medial Clavicular Head to the Manubrium in Normal and Symptomatic Degenerated Sternoclavicular Joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tavakkolizadeh A, Hales PF, Janes GC. Arthroscopic excision of sternoclavicular joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:405-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |