Published online Apr 18, 2017. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i4.329

Peer-review started: October 12, 2016

First decision: December 13, 2016

Revised: December 16, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 14, 2017

Published online: April 18, 2017

Processing time: 190 Days and 11.7 Hours

To quantify the variability of financial disclosures by authors presenting orthopaedic trauma research.

Self-reported authorship disclosure information published for the 2012 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) meetings was compiled from meeting programs. Both the AAOS and OTA required global disclosures for participants. Data collected included: (1) total number of presenters; (2) number of presenters with financial disclosures; (3) number of disclosures per author; (4) total number of companies supporting each author; and (5) specific type of disclosure. Disclosures made by authors presenting at more than one meeting were then compared for discrepancies.

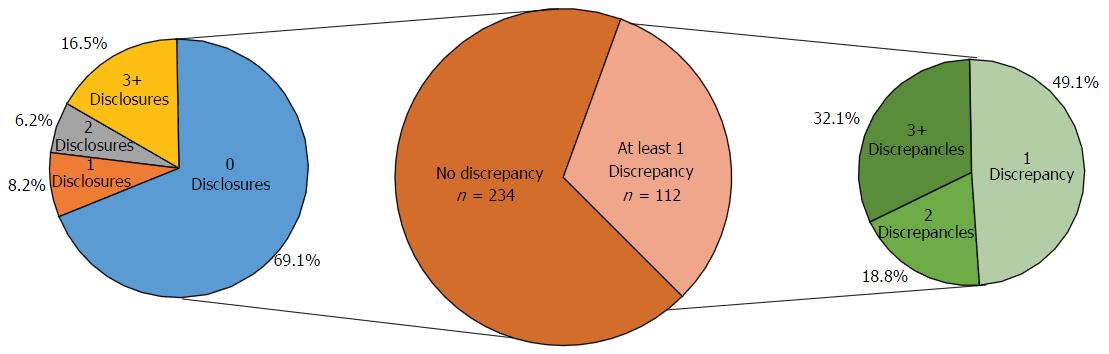

Of the 5002 and 1168 authors presenting at the AAOS and OTA annual meetings, respectively, 1649 (33%) and 246 (21.9%) reported a financial disclosure (P < 0.0001). At the AAOS conference, the mean number of disclosures among presenters with disclosures was 4.01 with a range from 1 to 44. The majority of authors with disclosures reported three or more disclosures (n = 876, 53.1%). The most common cited disclosure was as a paid consultant (51.5%) followed by research support (43.0%) and paid speaker (34.8%). Among the 256 physicians with financial disclosures presenting at the OTA conference, the mean number of disclosures was 4.03 with a range from 1 to 22. Similar to the AAOS conference, the majority of authors with any disclosures at the OTA conference reported three or more disclosures (n = 140, 54.7%). Most authors with a disclosure had three or more disclosures and the most common type of disclosure was paid consulting. At the OTA conference, the most commonly cited form of disclosure was paid consultant (54.3%) followed by research support (46.1%) and paid speaker (42.6%). Of the 346 researchers who presented at both meetings, 112 (32.4%) authors were found to have at least one disclosure discrepancy. Among authors with a discrepancy, 36 (32.1%) had three or more discrepancies.

There were variability and inconsistencies in financial disclosures by researchers presenting orthopaedic trauma research. Improved transparency of conflict of interest disclosures is warranted among trauma researchers presenting at national meetings.

Core tip: Previous studies have demonstrated discrepancies in financial conflict of interest disclosures among physicians presenting research. The purpose of this study was to quantify the variability of self-reported financial disclosures by authors presenting at multiple trauma conferences during the same year. The disclosures published for the 2012 annual meetings of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery and Orthopaedic Trauma Association were tabulated and disclosures made by authors presenting at both meetings were compared for discrepancies. Our results demonstrate variability in reported disclosures by authors presenting at multiple conferences within the same year. Further work is warranted to improve transparency of disclosures.

- Citation: Wong K, Yi PH, Mohan R, Choo KJ. Variability in conflict of interest disclosures by physicians presenting trauma research. World J Orthop 2017; 8(4): 329-335

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v8/i4/329.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v8.i4.329

Private industry has become an increasingly significant source of funding for physicians conducting research in recent years[1-3]. As industry investment in medical research grows however, conflict of interest (COI) has become a controversial topic in orthopaedic surgery. Many studies have suggested that close ties between industry and physicians may negatively influence the quality and integrity of clinical studies[4-6]. For example, industry funding is one of the strongest predictors for a favorable result in a product being studied[7-11]. Although industry funding has a potential to create bias, it has also been essential in achieving many advances in diagnosis and treatment in medicine[12], and as a result balancing the benefits and risks of industry relationships has become a divisive reality to deal with within the orthopaedic community.

Disclosures of conflict of interest have been called for by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and other medical organizations in order to maintain research integrity[13-16]. Unfortunately, differences in what constitutes a COI as well as ambiguity between disclosure guidelines between different organizations can make it difficult for physicians to know exactly what to disclose[15,17]. Previous studies have shown variability in the COI disclosures by researchers presenting on spine surgery and sports medicine, possibly due to variability in disclosure policies[18,19]. In fact, some evidence suggests that inaccuracies in COI disclosure can be found throughout the field of orthopaedics as a whole[20]. To date, however, there has been no previous analysis of COI discrepancies within the subspecialty of orthopaedic trauma.

The purpose of the present study was: (1) to describe the COI disclosures of authors presenting research at both the AAOS and the OTA annual meetings; and (2) to quantify variability in COI disclosures of authors who presented orthopaedic trauma research. We hypothesized that there would be variability in the disclosure of physicians presenting research at the two conferences in the same given year.

We recorded the disclosures from all authors who presented trauma research at two orthopedic conferences. The two conferences included in the study were the 2012 annual meeting for the AAOS and the 2012 annual meeting for the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA). Self-reported disclosure data from the authors for each conference was collected from the printed meeting information, which is available online[21,22]. Since the 2012 AAOS abstract deadline was in June 2011 while the 2012 OTA conference abstract deadline was in February 2012, it is possible that industry support and COI for some authors may have changed during the time between the two conferences. However, it is common for industry sponsorships to last for years, especially when these partnerships involve clinical research[23,24]. Thus, for the purposes of this current study, it was assumed that changes, if any, would be minimal given the relatively short time between the two conference deadlines.

The disclosure policies for the AAOS and OTA conferences were obtained from the AAOS and OTA websites[25]. Both the AAOS and OTA conferences required global disclosure (i.e., presenters were required to disclose all financial relationships, regardless of relevance to their presentation). Because the guidelines between these two conferences were equivalent, we were able to compare the financial relationships reported by authors who attended both conferences in order to quantify any discrepancies present in the author’s disclosures. Only authors who presented at both conferences were included in the present study for a total of 346 individuals. Researchers who presented at only one of the conferences were excluded from the study.

Pertinent characteristics recorded from each conference included: (1) total number of presenters; (2) number of presenters with financial disclosures; (3) number of disclosures per author (among authors with disclosures); (4) total number of companies/entities supporting each author (among authors with disclosures); and (5) percentage breakdown of each type of disclosure into 9 specific categories (i.e., royalties, paid speaker, employee, paid consultant, nonpaid consultant, stock options, research support, other support, and publishers).

After recording disclosure data from each conference for eligible authors, the disclosures between the two conferences were then compared. First, the total number of authors with and without consistent number of disclosures was recorded. Next the individuals with inconsistent disclosures were categorized into two categories: (1) those who disclosed at least one financial relationship at one conference but no financial relationships at the other conference; and (2) those who disclosed at both conferences but with different number and type of disclosures.

The total number of research presenters at the AAOS annual meeting was 5002, and out of those who presented, 1649 (33.0%) had financial disclosures. The total number of presenters at the OTA annual meeting was 1168 and a total of 256 (21.9%) authors at the OTA meeting had financial disclosures. In total there were 6613 disclosures reported at the AAOS meeting and 1033 disclosures reported at the OTA meeting.

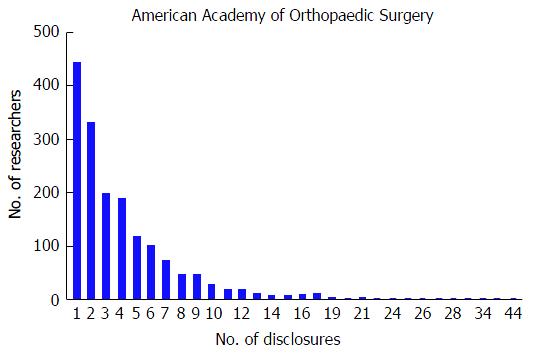

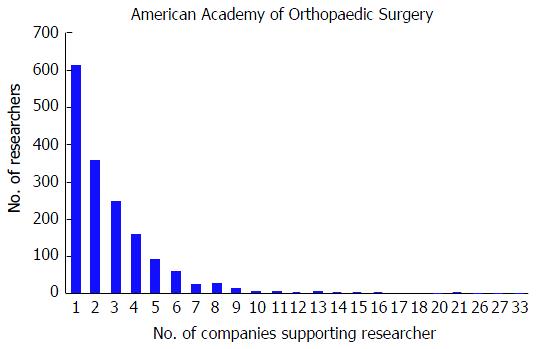

At the AAOS conference, the mean number of disclosures among presenters with disclosures was 4.01 with a range from 1 to 44. The majority of authors with disclosures reported three or more disclosures (n = 876, 53.1%); in contrast, only 443 (26.9%) researchers reported one disclosure and 330 (20.0%) of researchers reported two disclosures. Although the majority of authors reported three or more disclosures, the number of researchers reporting increasing number of disclosures progressively decreases (Figure 1). The mean number of companies/entities supporting researchers among those with disclosures was 2.88 with a range from 1 to 33 companies. Of those authors with support from companies, 612 (37.1%) researchers received support from only one company, 358 (21.7%) received support from two companies, and 679 (41.2%) received support from three or more companies. Similar to the total number of disclosures, the number of researchers disclosing company/entity support decreases as the number of disclosures increases (Figure 2). Among authors who provided specific types of disclosures, the most common cited disclosure was as a paid consultant (51.5%) followed by research support (43.0%) and paid speaker (34.8%). In descending order, the remaining disclosures include royalties (29.1%), stock options (27.9%), publisher (17.5%), unpaid consultant (11.7%), other support (11.0%), and employee (5.15%).

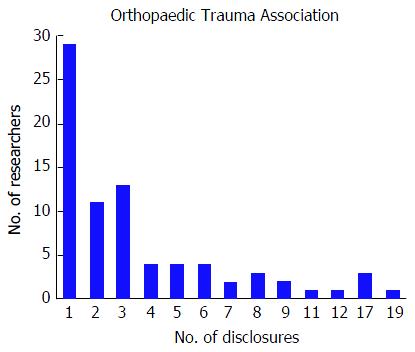

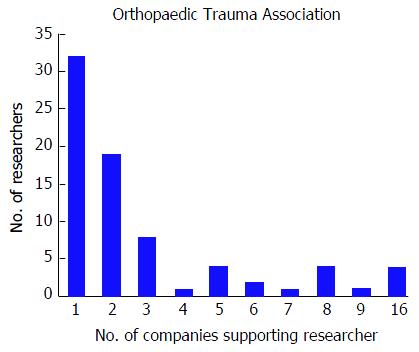

Among the 256 physicians with financial disclosures presenting at the OTA conference, the mean number of disclosures was 4.03 with a range from 1 to 22. Similar to the AAOS conference, the majority of authors with any disclosures reported three or more disclosures (n = 140, 54.7%), a total of 61 (23.8%) presenters reported only one disclosure and 55 (21.5%) of presenters reported two disclosures. Although the majority of authors who reported any disclosures at the OTA conference reported three or more financial affiliations, the number of researchers reporting sequentially increasing number of affiliations decreases (Figure 3). The mean number of companies/entities supporting researchers who reported disclosures was 3.09 with a range from 1 to 22 companies. Of those presenters who received support from companies, 78 (30.5%) researchers received support from only one company, 69 (27.0%) researchers received support from two companies, and 109 (42.6%) researchers received support from three or more companies. The number of physicians disclosing support from companies decreases at successively higher numbers of company support (Figure 4). Among presenters who provided specific types of financial disclosures, the most commonly cited form of disclosure was paid consultant (54.3%) followed by research support (46.1%) and paid speaker (42.6%). In descending order, the remaining disclosures include stock options (23.4%), royalties (19.5%), publisher (16.8%), other support (13.3%), unpaid consultant (12.1%), and employee (6.25%).

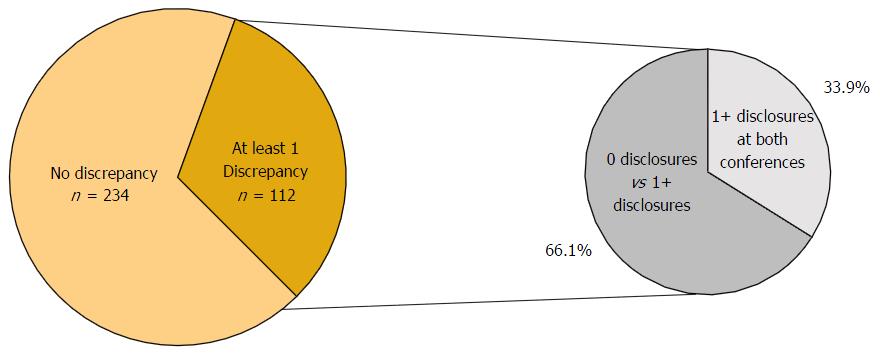

In total, 346 physicians presented at both the AAOS and OTA conferences in 2012. The number of co-presenters with discrepancies in financial disclosure was 112 (32.4%) with a mean of 2.47 and a range from 1 to 16 discrepancies. Among the co-presenters with disclosures, 55 (49.1%) had one discrepancy between the AAOS and OTA conferences, 21 (18.8%) of co-presenters had two discrepancies between the two conferences, and 36 (32.1%) of co-presenters had three or more discrepancies between the two conferences (Figure 5). Of the 112 co-presenters with discrepancies, 38 (33.9%) made zero disclosures at one conference but disclosed at least one financial relationship at the other conference while 74 (66.1%) of co-presenters with discrepancies disclosed at both conferences (Figure 6). The remaining 67.6% of physicians who presented at both conferences were found to have no discrepancies between their disclosures.

As funding for biomedical research has shifted significantly towards private industry[26], addressing COI has become an important topic for orthopaedic surgeons. Although previous studies have demonstrated disclosure inconsistencies by physicians presenting sports medicine and spine surgery at various orthopaedic conferences[18,19], no previous study has assessed the variability of COI disclosures by physicians presenting orthopaedic trauma research. The purpose of this study was to evaluate disclosures by physicians presenting at the 2012 AAOS and OTA annual meetings in order to quantify COI discrepancies. Overall, we found a high prevalence of disclosure discrepancies. Nevertheless, specific types of disclosures were similar between presenters at both the AAOS and OTA conferences; furthermore, the most common disclosure types were paid consulting, research support, and paid speaker. Finally, we found that the majority of physicians with discrepancies had more than one discrepancy, and a large portion of physicians with discrepancies disclosed nothing at one conference despite disclosing at least one COI at the other conference.

There was a high prevalence of disclosure discrepancies by physicians who presented at both the 2012 AAOS and OTA conferences with a total of about one third of all physicians with at least one discrepancy. This is consistent with previous reports in sports medicine and spine, which have also shown high discrepancy rates among researchers presenting in these fields. There are several possible explanations for this high number of discrepancies. First, it is possible that discrepancies between the two conferences can be explained simply by natural changes in industry affiliations that occurred between the two conferences; however the period of only a few months between conference abstract submission deadlines makes this explanation unlikely. A second possibility is that the discrepancies simply result from physician carelessness. Current penalties for inaccurate disclosure are fairly limited and leave researchers considerable discretion in what they decide to disclose[16,27]; lack of sufficient repercussion may decrease the effort some authors make in order to check or verify disclosure policies, leading to disclosure errors. This carelessness might also explain the difference in total disclosures between the AAOS and OTA conferences: The AAOS is a larger conference, and hosts not only a higher number of attendees, but also features a larger number of orthopaedic topics including but not limited to trauma[28]. While it is possible that some physicians correctly assumed a global disclosure policy at the AAOS conference given the larger scope of the conference, when these same physicians presented at the OTA conference - a conference focused on a more niche topic - they may have erroneously assumed that they only needed to disclose project-specific industry relationships without checking for the true OTA global disclosure policy. This possibility is consistent with our data, which showed an increase in the proportion of physicians reporting disclosures at the AAOS conference compared to the OTA conference.

The three most common types of disclosures in descending order were paid consultant, research support, and paid speaker. These observations are consistent with previous studies within the fields of spine surgery, sports medicine, and pediatric orthopaedics, which have also been shown to have the same three most frequent financial relationships[29]. General trends in paid consultancies are also commonplace in total joint arthroplasty, with manufacturers often paying physicians to serve as experts[30]. These findings demonstrate that industry funding has become such a consistent factor in orthopaedic research that even the type of disclosures remains steady between orthopaedic trauma and other orthopaedic specialties. However the prevalence of industry funding within orthopaedic research is not necessarily detrimental. As we have already mentioned, industry funding in itself does not automatically decrease the credibility or validity of research. Secondly, the presence of industry funding in multiple orthopaedic specialties may actually be beneficial by providing an opportunity to compare rates of disclosure discrepancies between specialties and identify areas with lower discrepancies. This would ultimately be beneficial for orthopaedic trauma research by allowing researchers to adopt successful strategies to reduce COI discrepancies within this field.

Meaningful research requires more than proper technique and procedure, it also requires proper disclosure of conflicts of interest[31,32]. The inability of current disclosure guidelines to facilitate uniform and accurate physician disclosure regarding orthopaedic trauma research is demonstrated by the high variability in both the number and type of disclosure inconsistencies. Our data has shown that the majority of physicians with discrepancies in disclosure presented with more than one discrepancy. Furthermore, over a third of physicians who reported at least one disclosure at one conference failed to report any COI at the other conference. Proper disclosure is crucial to inform the audience and allow readers to draw their own conclusions about the objectivity of the research[33]. At a time when the public is often cautious and even skeptical towards medical research, disclosure inconsistencies may negatively impact the integrity of research, and it is therefore important that orthopaedic surgeons hold themselves to a high standard of accuracy and decrease the inconsistencies in both the number and type of disclosures.

There were several limitations to our study. As previously mentioned, the AAOS and OTA conferences occurred during different months so there may have been changes in financial affiliations during that time. The disclosure deadline for the 2012 AAOS conference was June 2011 while the disclosure deadline for the 2012 OTA conference was February 2011. In these nine months, we predicted that there would only be minor changes, if any, in disclosures by anyone presenting at both conferences. Another limitation to our study was the fact that only two orthopaedic conferences were examined in this study. For this reason, the sampling of physician disclosures may not be representative of the total population of disclosures in orthopaedic trauma research, nor can the findings be generalized towards non-orthopaedic research. Nevertheless, we believe that our data does provide accurate insight into the realities of two of the most prominent venues for the presentation of orthopaedic trauma research in the world, and as such is relevant to the discussion of COI in orthopaedics.

In our study, we found substantial variability in disclosures from physicians presenting orthopaedic trauma research at the 2012 AAOS and OTA conferences. The origin of financial relationships between researchers and industry arise from multiple sources, and there is variability in both the number and type of discrepancies involved in trauma research. The large proportion of disclosure inconsistencies currently found in physicians presenting trauma research may be explained by factors such as physician carelessness, unclear disclosure instructions, or inadequate repercussions by the AAOS and OTA for failure to accurately disclose. Because the current system presents with a high number of disclosure discrepancies within orthopaedic trauma, we recommend adjusting current guidelines to be more clear and uniform as a first step in promoting accurate COI disclosure as well as research transparency and accountability.

Private industry has become an increasingly significant source of research funding. Financial relationships may create biases that compromise the integrity and objectivity of industry-sponsored medical research. To improve transparency, multiple orthopaedic organizations have developed specific disclosure policies. Unfortunately, current guidelines vary between organizations and are often not clearly explained to researchers. The purpose of this study was to quantify the variability of financial disclosures by authors presenting orthopaedic trauma research.

Previous studies in sports medicine, spine surgery, and arthroplasty have shown that researchers presenting at separate national meetings within the same academic year have discrepancies in the financial disclosures they make.

This is the first study to our knowledge that has investigated: (1) the prevalence and characteristics of financial relationships; and (2) quantified discrepancies in conflict of interest disclosures by researchers presenting orthopaedic trauma research. The results of their study demonstrate that many authors reported financial disclosures at American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Orthopaedic Trauma Association, with a relatively high number of discrepancies.

Clearer instructions for authors regarding financial disclosures should be established in order to help make conflict of interest disclosures a more reliable and appropriate measure.

A “conflict of interest” is defined as a situation in which a person or organization is involved in multiple personal or financial interests that may corrupt or otherwise influence the motivation and decision-making abilities of that individual.

The paper is an excellent paper with very important topic: Variability in conflict of interest disclosures by physicians presenting trauma research.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Emara KM, Guerado E, Peng BG S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Boyd EA, Bero LA. Assessing faculty financial relationships with industry: A case study. JAMA. 2000;284:2209-2214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Blumenthal D, Causino N, Campbell E, Louis KS. Relationships between academic institutions and industry in the life sciences--an industry survey. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:368-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Blumenthal D, Campbell EG, Causino N, Louis KS. Participation of life-science faculty in research relationships with industry. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1734-1739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Levine J, Gussow JD, Hastings D, Eccher A. Authors’ financial relationships with the food and beverage industry and their published positions on the fat substitute olestra. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:664-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kubiak EN, Park SS, Egol K, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. Increasingly conflicted: an analysis of conflicts of interest reported at the annual meetings of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2006;63:83-87. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Robertson C, Rose S, Kesselheim AS. Effect of financial relationships on the behaviors of health care professionals: a review of the evidence. J Law Med Ethics. 2012;40:452-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Perlis RH, Perlis CS, Wu Y, Hwang C, Joseph M, Nierenberg AA. Industry sponsorship and financial conflict of interest in the reporting of clinical trials in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1957-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tomaszewski C. Conflicts of interest: bias or boon? J Med Toxicol. 2006;2:51-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Djulbegovic B, Lacevic M, Cantor A, Fields KK, Bennett CL, Adams JR, Kuderer NM, Lyman GH. The uncertainty principle and industry-sponsored research. Lancet. 2000;356:635-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kjaergard LL, Als-Nielsen B. Association between competing interests and authors’ conclusions: epidemiological study of randomised clinical trials published in the BMJ. BMJ. 2002;325:249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:454-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1219] [Cited by in RCA: 1063] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lo B, Field MJ. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Conflict of Interest in Medical Research E and P. Conflicts of Interest in Biomedical Research, 2009. |

| 13. | Cho MK, Shohara R, Schissel A, Rennie D. Policies on faculty conflicts of interest at US universities. JAMA. 2000;284:2203-2208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krimsky S, Rothenberg LS. Conflict of interest policies in science and medical journals: editorial practices and author disclosures. Sci Eng Ethics. 2001;7:205-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cooper RJ, Gupta M, Wilkes MS, Hoffman JR. Conflict of Interest Disclosure Policies and Practices in Peer-reviewed Biomedical Journals. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1248-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Department of Health and Human Services. Responsibility of applicants for promoting objectivity in research for which public health service funding is sought and responsible prospective contractors. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76:53256-53293. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rowan-Legg A, Weijer C, Gao J, Fernandez C. A comparison of journal instructions regarding institutional review board approval and conflict-of-interest disclosure between 1995 and 2005. J Med Ethics. 2009;35:74-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jegede KA, Ju B, Miller CP, Whang P, Grauer JN. Quantifying the variability of financial disclosure information reported by authors presenting research at multiple sports medicine conferences. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2011;40:583-587. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ju BL, Miller CP, Whang PG, Grauer JN. Quantifying the variability of financial disclosure information reported by authors presenting at annual spine conferences. Spine J. 2011;11:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okike K, Kocher MS, Mehlman CT, Bhandari M. Conflict of interest in orthopaedic research. An association between findings and funding in scientific presentations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:608-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2012 Annual Meeting Education Disclosures. Available from: http://www.aaos.org/Education/anmeet/education/Disclosures.pdf. |

| 22. | HWB Foundation. OTA 2012 Disclosure Listing-Alphabetical. Available from: http://www.hwbf.org. |

| 23. | Thomas O, Thabane L, Douketis J, Chu R, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Industry funding and the reporting quality of large long-term weight loss trials. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1531-1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K, Lines C, Riddell R, Morton D, Lanas A, Konstam MA, Baron JA; Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1092-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1849] [Cited by in RCA: 1724] [Article Influence: 86.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Mandatory Disclosure Policy-AAOS. Available from: http://www.aaos.org/about/policies/DisclosurePolicy.asp. |

| 26. | Bodenheimer T. Uneasy alliance--clinical investigators and the pharmaceutical industry. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1539-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hanna J, Simiele E, Lawson DC, Tyler D. Conflict of interest issues pertinent to Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:50S-54S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Annual Meeting Programs-AAOS. Available from: http://www.aaos.org/education/anmeet/programs/Programs.asp. |

| 29. | Matsen FA, Jette JL, Neradilek MB. Demographics of disclosure of conflicts of interest at the 2011 annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tanne JH. US makers of joint replacements are fined for paying surgeons to use their devices. BMJ. 2007;335:1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hirsch LJ. Conflicts of interest, authorship, and disclosures in industry-related scientific publications: the tort bar and editorial oversight of medical journals. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:811-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Thompson DF. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:573-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 525] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cohen JJ. Trust us to make a difference: ensuring public confidence in the integrity of clinical research. Acad Med. 2001;76:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |