Published online Mar 18, 2017. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.286

Peer-review started: May 3, 2016

First decision: July 6, 2016

Revised: October 31, 2016

Accepted: December 27, 2016

Article in press: December 28, 2016

Published online: March 18, 2017

Processing time: 320 Days and 5.2 Hours

Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing has gained popularity as a feasible treatment option for young and active patients with hip osteoarthritis and high functional expectations. This procedure should only be performed by surgeons who have trained specifically in this technique. Preoperative planning is essential for hip resurfacing in order to execute a successful operation and preview any technical problems. The authors present a case of a man who underwent a resurfacing arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the left hip that was complicated by mismatched implant components that were revised three days afterwards for severe pain and leg length discrepancy. Such mistakes, although rare, can be prevented by educating operating room staff in the size and colour code tables provided by the companies on their prostheses or implant boxes.

Core tip: The authors present a case of a man who underwent a resurfacing arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the left hip that was complicated by mismatched implant components that were revised three days afterwards for severe pain and leg length discrepancy. Such mistakes, although rare, can be prevented by educating operating room staff in the size and colour code tables provided by the companies on their prostheses or implant boxes.

- Citation: Calistri A, Campbell P, Van Der Straeten C, De Smet KA. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty complicated by mismatched implant components. World J Orthop 2017; 8(3): 286-289

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v8/i3/286.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.286

Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing has gained popularity as a feasible treatment option for young and active patients with hip osteoarthritis and high functional expectations. This procedure is more technically challenging than routine total hip replacement, mainly for surgeons new to the procedure and it should only be performed by surgeons who have trained specifically in this technique. The learning curve is known to be longer than in other hip arthroplasty procedures and is expected to be more than 50-70 surgeries[1,2]. During the learning curve the surgeon should follow the technique thoroughly. Preoperative planning is essential for hip resurfacing[3]. This step is important to help the surgeon perform a successful procedure and preview any technical problems.

The correct placement of both acetabular and femoral components is critical for the optimal functioning of the bearings. A smooth surface and perfect clearance are the key factors for the bearing, but equally important is the need for optimal placement to ensure good clinical results. High abduction angles and impingement will lead to early wear of the metal-on-metal articulation[4]. The problem of malpositioned components is becoming increasingly recognized as the cause of premature failure. An unusual cause for failure is the accidental implantation of mismatched components[5]. One such case is described below.

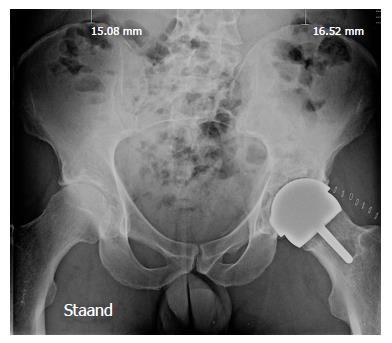

In July 2007, a 51 years old man was admitted at the ANCA Medical Centre in Gent with a mismatch of implants. Three days prior, at another hospital, the patient underwent a resurfacing arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the left hip, with a posterior approach assisted with computer navigation (Brainlab®). A Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (Smith and Nephew, Memphis, Tennessee) was used. In the recovery room, the patient complained of severe pain and a rigid immobility of the hip that did not disappear the day after surgery. The patient at clinical examination presented a flection contracture on the right side and pain in the groin. X-rays confirmed a mismatch between the femoral and the acetabular component diameters (Figure 1). A size 56-mm cemented femoral component was combined with a size 62-mm cementless acetabular component thick shell that should have been applied with a 54-mm head instead of a 56-mm head.

The patient was treated with a revision to total hip arthroplasty two days later with the same posterolateral approach. The femoral component was revised with a Profemur L stem (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, Tennessee, United States) and the socket was replaced by a Pinnacle™ Acetabular Cup System (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc., Warsaw, United States) with Delta on Delta Biolox Ceramic couple 36 mm. Routine post-operative thrombo-prophylaxis was carried out. He experienced no pain and was allowed full weight bearing the day after revision surgery. The patient experienced an ordinary postoperative course and was habitually followed up in outpatient clinic.

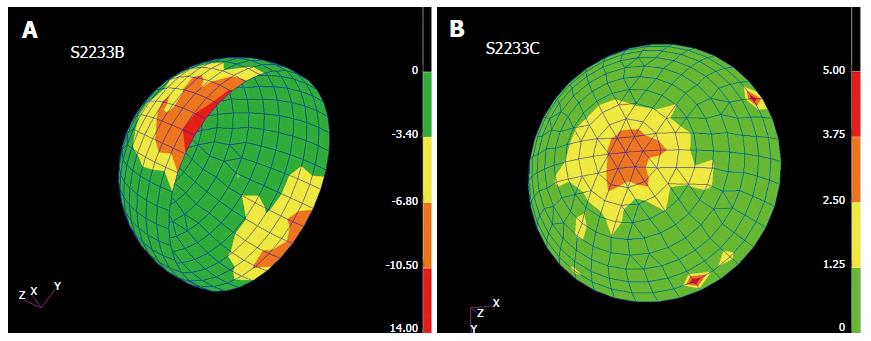

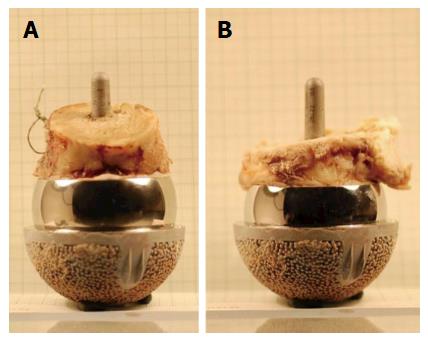

The implants were analysed using a coordinate measuring machine to measure both components. This confirmed the size mismatch; the femoral component was 55.75 mm while the acetabular component was 54.054 mm. The coordinate measuring machines (CMM) map indicated damage to the femoral component) (Figure 2). The effect of the mismatched sizing is demonstrated by comparing the removed components to a correctly sized set using a 54-mm femoral component obtained from the retrieval lab (Figure 3).

There is a decreasing demand and interest from orthopaedic surgeons for hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Consequently, from a peak of 14 implant manufacturers, currently only 8 different MOM hip resurfacing implants are available for use in clinical practice in Britain and Europe. For each design, there can be special sizes with different increments.

To help operating room staff to select the appropriately matched implants, some manufacturers provide a colour chart to show the size of the femoral head that the surgeon can match with the corresponding different acetabular sizes, with the same colour code.

In this present case report, despite various colour codes, the improper components were selected during the case. The thin shell component, cup size 62-mm was requested but the 62-mm thick shell which can be used only with a 54-mm head was mistakenly provided instead. This thick shell is a special acetabular component that can be used for particular cases of head/neck mismatch or hip articulation deformity such as coxa profunda and protrusion acetabuli.

In the literature, Hanks et al[6] reported this technical complication in total hip arthroplasty; in two cases the head size of the femoral component was larger than the corresponding inner diameter of the acetabular cup. The author suggests that the error can be prevented with a careful preoperative planning and appropriate selection of implants.

Morlock et al[7] published on a mismatched zirconium/aluminium oxide couple with high wear in a total hip arthroplasty in a patient that had a squeaking noise but with good clinical function. No signs of loosening were detected on the radiograph. The revision was performed 42 mo after the first surgery. The analysis of the retrievals showed that the cup had large deviations from an ideal sphere but minor wear signs and the head revealed heavy local damage in the articulation zone resulting in high stress concentrations and increased wear of the zirconium head.

One of the advantages of hip resurfacing is an easier conversion to a secondary procedure if failure occurs[8]. In this case an early revision was necessary for the pain and leg length difference the patient was experiencing. The retrieval analysis of this case revealed no clear damage to the acetabular component but there was damage to the femoral component. More importantly, lack of proper contact between the ball and the cup presented the risk of high wear with metallosis if the mismatched components had been allowed to be used. It has also been established that wear and degradation particles are released into the periprosthetic tissues and transported systemically throughout the body[9]. Furthermore, there was also a risk that the increased torque between the mismatched bearings could have compromised fixation and stability.

Operating room staff needs to be reminded to pay careful attention to component size markings, particularly in the designs where more acetabular component sizes exist for one femoral component size. Implants also only can be matched if they are from the same manufacturer. The tight clearance specifications that make these implants work well can be dramatically mismatched if implants from different manufacturers are mixed. As seen in the present case, some implants labelled or marked as 55-mm head (nominal size), are in reality 55.5-mm. If these are matched with a real 55 mm internal diameter cup from another design we would have an equatorial mismatch with all of the attendant complications and high wear.

Care should be taken in the theatre to provide the surgeon with the correct implants. Mistakes only can be prevented by a well trained team of nurses and assistants, and they must be familiar with the size and colour code tables provided by the company on the prostheses or implant boxes. All companies should provide the surgeons with a chart that shows all different increments of the femoral head and cup sizes that can be matched together.

The authors are grateful to Dr. Zhen Lu of Orthopaedic Institute for Children/UCLA for performing the CMM analysis.

A 51-year-old man was admitted at our institution with a mismatch of implants.

The patient at clinical examination presented a flection contracture on the right side and pain in the groin.

Coordinate measuring machines (CMM) wear measurement of the mismatched couple showed that the femoral component had already been damaged.

X-ray.

The patient was treated with a revision to total hip arthroplasty two days later with the same posterolateral approach. The femoral component was revised with a Profemur L stem (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, Tennessee, United States) and the socket was replaced by a Pinnacle™ Acetabular Cup System (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc., Warsaw, United States) with Delta on Delta Biolox Ceramic couple 36 mm.

CMM is a technique that has been widely used for dimensional inspection of complex shaped objects both for evaluating their shape which can be used to estimate wear distribution over the surface.

The authors reported a case of a patient underwent a hip resurfacing arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the left hip that was complicated by mismatched implant components. They also reported the results of the patient treated with a revision to total hip arthroplasty two days later. As a typical case report, it could be accepted for publication.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Malik H, Song GB, Solomon LB S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Mont MA, Ragland PS, Etienne G, Seyler TM, Schmalzried TP. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:454-463. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lachiewicz PF. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing: a skeptic’s view. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465:86-91. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Amstutz HC, Beaulé PE, Dorey FJ, Le Duff MJ, Campbell PA, Gruen TA. Metal-on-metal hybrid surface arthroplasty. Surgical Technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 Suppl 1 Pt 2:234-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Haan R, Pattyn C, Gill HS, Murray DW, Campbell PA, De Smet K. Correlation between inclination of the acetabular component and metal ion levels in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1291-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Haan R, Campbell PA, Su EP, De Smet KA. Revision of metal-on-metal resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: the influence of malpositioning of the components. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1158-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hanks GA, Foster WC, Cardea JA. Total hip arthroplasty complicated by mismatched implant sizes. Report of two cases. J Arthroplasty. 1986;1:279-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Morlock M, Nassutt R, Janssen R, Willmann G, Honl M. Mismatched wear couple zirconium oxide and aluminum oxide in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:1071-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | De Smet KA. Belgium experience with metal-on-metal surface arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:203-213, ix. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Savarino L, Granchi D, Ciapetti G, Cenni E, Nardi Pantoli A, Rotini R, Veronesi CA, Baldini N, Giunti A. Ion release in patients with metal-on-metal hip bearings in total joint replacement: a comparison with metal-on-polyethylene bearings. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63:467-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |