Published online Mar 18, 2017. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.264

Peer-review started: June 6, 2016

First decision: July 5, 2016

Revised: November 14, 2016

Accepted: December 1, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

Published online: March 18, 2017

Processing time: 285 Days and 12.2 Hours

To investigate success of one stage exchange with retention of fixed acetabular cup.

Fifteen patients treated by single stage acetabular component exchange with retention of well-fixed femoral component in infected total hip arthroplasty (THA) were retrospectively reviewed. Inclusion criteria were patients with painful chronic infected total hip. The patient had radiologically well fixed femoral components, absence of major soft tissue or bone defect compromising, and infecting organism was not poly or virulent micro-organism. The organisms were identified preoperatively in 14 patients (93.3%), coagulase negative Staphylococcus was the infecting organism in 8 patients (53.3%).

Mean age of the patients at surgery was 58.93 (± 10.67) years. Mean follow-up was 102.8 mo (36-217 mo, SD 56.4). Fourteen patients had no recurrence of the infection; one hip (6.7%) was revised for management of infection. Statistical analysis using Kaplan Meier curve showed 93.3% survival rate. One failure in our series; the infection recurred after 14 mo, the patient was treated successfully with surgical intervention by irrigation, and debridement and liner exchange. Two complications: The first patient had recurrent hip dislocation 12 years following the definitive procedure, which was managed by revision THA with abductor reconstruction and constrained acetabular liner; the second complication was aseptic loosening of the acetabular component 2 years following the definitive procedure.

Successful in management of infected THA when following criteria are met; well-fixed stem, no draining sinuses, non-immune compromised patients, and infection with sensitive organisms.

Core tip: Peri-prosthetic hip infection is a devastating complication: We hypothesized that a well-fixed circumferentially ingrown cement-less stem can act as a shield and prevent the spread of pathogens and formation of biofilm around the body of the femoral stem. Therefore, single stage exchange of the acetabular component with retention of the well-fixed femoral component can be a successful option in management of infected total hip arthroplasty, when the following criteria are met; well-fixed femoral component, no draining sinuses, non immune compromised patients, and infection with sensitive organisms.

- Citation: Rahman WA, Kazi HA, Gollish JD. Results of single stage exchange arthroplasty with retention of well fixed cement-less femoral component in management of infected total hip arthroplasty. World J Orthop 2017; 8(3): 264-270

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v8/i3/264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.264

Peri-prosthetic hip infection is a devastating complication, up to 2% of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) and 4%-6% after revision THA are complicated by infection[1,2]. The goal of treatment is eradication of infection and durable functional reconstruction[3,4]. There are variable surgical options for management of infected THA. Two-stage exchange arthroplasty has been considered the gold standard treatment[5-7]. However, it is expensive and associated with high rates of surgical morbidity[8-11]. One-stage exchange arthroplasty remains an attractive alternative option since it requires only one operation, and is associated with shorter hospital stay and faster rehabilitation[12-15]. Previous studies have shown good results of single stage exchange arthroplasty with preservation of a well-fixed cement mantle[16].

We hypothesized that a well-fixed circumferentially ingrown cement-less stem can act as a shield and prevent the spread of pathogens and formation of biofilm around the body of the femoral stem. Therefore, single stage exchange of the acetabular component with retention of the well-fixed femoral component can be a successful option in management of infected total hip arthroplasty, when the following criteria are met; well-fixed femoral component, no draining sinuses, non immune compromised patients, and infection with sensitive organisms. Failure of treatment was defined by recurrence of infection that required either further surgical intervention or the use of long-term suppressive antibiotics.

Research Ethics Board approved this retrospective study at our institution. The Electronic Patient Record was searched for the patients who had single stage acetabular component exchange with retention of a well-fixed femoral component in management of infected THA.

From January 1997 to January 2012, 15 hips in 15 patients (9 females and 6 males) were managed with single stage acetabular component exchange with preservation of well-fixed femoral component. Inclusion criteria were patients with painful chronic infected total hip diagnosed with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, ≥ 30 mm/h) and /or C-reactive protein (CRP, ≥ 20 mg/L) and/or elevated white blood cell count > 11000. The patient had the following criteria; radiologically well fixed femoral components, absence of major soft tissue defect compromising wound closure and/or bone defect affecting implant stability, and infection was not associated with culture of polymicrobial or antibiotic resistant micro-organism in the preoperative hip aspiration culture.

Our exclusion criteria were patients presented with a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis, culture of MRSA or poly-microbial infection, immunocompromised patients, patients treated previously for management of infected THA with either one or two stage exchange arthroplasty, radiological signs of loosening of the femoral component, and if the femoral component was discovered to be loose during the surgical procedure.

All the patients included in the study were consented for single stage acetabular component exchange or two-stage exchange arthroplasty if the were intra-operative finding of loose femoral component, or highly contaminated hip joint with purulent material and extensive damage of the soft tissue.

Mean age of the patients at operation was 58.93 years (range; 38-76 years, SD 10.6). Patient body mass index averaged 30 kg/m2 (range; 18-51 kg/m2, SD 8.8). ASA level was I (n = 3), II (n = 5), III (n = 6), and IV (n = 1). Eleven patients were non-smokers, while 4 patients were smokers. The patients had the following comorbidities; diabetes mellitus (n = 2), hypertension (n = 6), myocardial infarction (n = 1), hyper lipdemia (n = 2) and rheumatoid arthritis (n = 1) (Table 1). Surgical procedures before infection were primary total hip arthroplasty in (n = 11), and revision total hip arthroplasty in (n = 4); cup revision for aseptic loosening of the acetabular component (n = 1), linear exchange for management of poly wear (n = 1) and irrigation and debridement for management of acute infection in (n = 2). The mean interval between the previous primary total hip arthroplasty and single stage acetabular component exchange was 78.6 mo, SD 75.86 (range; 12-242 mo).

| Patient | Sex | Age | Pre ESR | Pre CRP | Re culture | Complication | Revision details | Culture in revision | Failure |

| 1 | F | 38 | NA | NA | Gram negative cocci | Recurrentdislocation | Constrained liner | None | No |

| 2 | F | 44 | 37 | 27 | Coagulase negative staph | No | |||

| 3 | F | 47 | 33 | 44 | Beta hemolytic street | No | |||

| 4 | F | 53 | 50 | 46 | Beta hemolytic street | Aseptic loosening acetabular component | Revision cup | None | No |

| 5 | F | 55 | 50 | 80 | No growth | No | |||

| 6 | F | 65 | 44 | 57 | Beta hemolytic street | No | |||

| 7 | F | 68 | 30 | 26 | Coagulase negative staph | No | |||

| 8 | F | 70 | 55 | 82 | Beta hemolytic street | No | |||

| 9 | M | 77 | 60 | 130 | Coagulase negative staph | No | |||

| 10 | M | 58 | 50 | 30 | Coagulase negative staph | Infection | Debridement and liner exchange | Coagulase negative staph | Yes |

| 11 | M | 60 | 65 | 102 | Coagulase negative staph | No | |||

| 12 | M | 65 | 49 | 86 | Coagulase negative staph | No | |||

| 13 | M | 65 | 63 | 30 | Coagulase negative staph | No | |||

| 14 | M | 52 | 25 | 45 | Gram negative cocci | No | |||

| 15 | M | 68 | 24 | 40 | Coagulase negative staph | No |

The organisms were identified from the aspirated fluid before single stage acetabular component exchange in 14 patients (93.3%), no organism was identified in 1 hips (6.7%), coagulase negative staphylococcus was the infecting organism in 8 patients (53.3%). Details of the infecting organism are summarized in (Table 2). All the patients included in the study an un-cemented acetabular and femoral components.

| Characteristics | n of patients |

| Hip joints | 15 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 6 |

| Female | 9 |

| Age at index surgery: Mean, (SD), range | 58.93 yr, SD 10.6 (range; 38-76 yr) |

| BMI kg/m2, SD, range | 30, SD 8.8 (range; 18-51) |

| ASA INDEX | |

| I | 3 |

| II | 5 |

| III | 6 |

| IV | 1 |

| Smoking | |

| Non smoker | 11 |

| Smoker | 4 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 |

| Hypertension | 6 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 |

| Hyperlipdemia | 2 |

| Patients with previous cardiac history (myocardial infarction) | 1 |

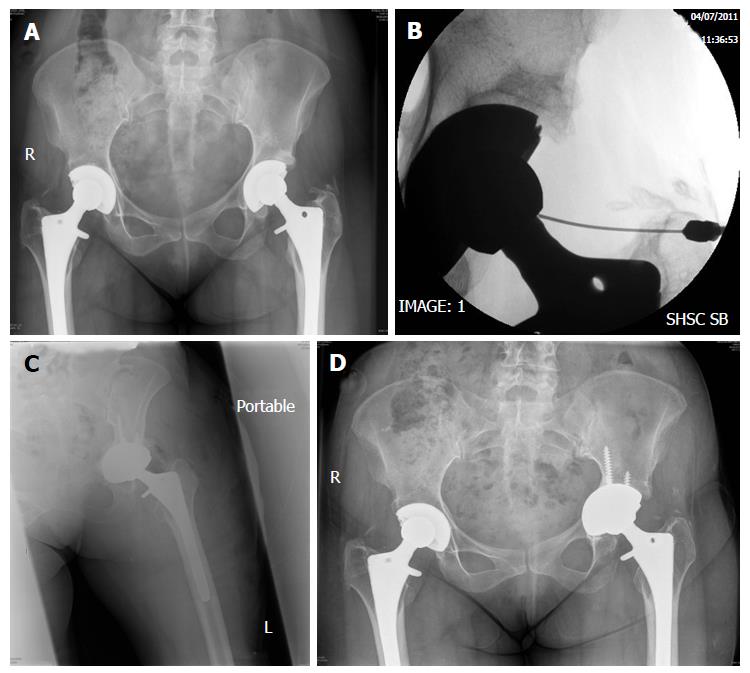

During the operative procedure, aggressive debridement of the joint was performed; 5 tissue samples were sent for microbiological analysis. All the patients received intra-operative prophylactic antibiotics after obtaining the soft tissue cultures. All the femoral components were assessed intra-operatively and were well–fixed. Mechanical cleansing with diluted povidine- iodine was used to clean the exposed metal parts of the femoral component. The acetabular components were loose in 6 hips, fibrous ingrown in 6 hips, and well fixed in 3 hips which required use of the Explant system (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, United States). The acetabular component, liner and femoral head were removed carefully with minimal damage of the bone stock (Figure 1).

A through irrigation was done again using 3 L of saline using pulsatile lavage and one liter of diluted povidine-iodine. The instruments were changed and the patients were re-draped before re-implantation. Cement less acetabular component, high cross-linked polyethylene liner, and cobalt chrome femoral head were used in all the patients included in the study. The acetabular components used in the definitive procedure were as follows; Trilogy (n = 13), HGP II (n = 1) and Trabecular metal modular cup (n = 1) (Zimmer Inc., Warsaw, IN). No drain was used and closure of the hip abductors, Illiotibial band, and subcutaneous tissue were performed with non-absorbable suture (coated VICRYL; Ethicon, Johnson and Johnson, Cornelia, GA), followed by sub-cuticular suture for skin closure. AQUA CELL AG surgical dressing (ConvaTec INC, Greensboro, NC) was used for wound dressing.

All patients were evaluated and managed by the infectious diseases team in our hospital. Postoperatively, the patients were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics until the results of the culture were available. Organism-specific IV antibiotics were administered for 6 wk. Antibiotics used were cloxacillin (n = 8), Vancomycin (n = 3), Clindamycin (n = 2), cephazolin (n = 1) and cefatriaxone (n = 1). After discontinuation of the intravenous antibiotics, all the patients continued on oral antibiotics for additional 6 wk, cloxacillin (n = 12), and ciprofloxacin (n = 3).

At follow-up, the patients were seen at 6 wk, 3, 6, 9, 12 mo and annually thereafter. Clinical, radiological and laboratory evaluation (using serial white cell count, ESR, and CRP) was performed at each follow up.

Mean follow-up was 102.8 mo (36-217 mo, SD 56.4). No patients were lost to follow-up. Fourteen patients had no recurrence of the infection; one hip (6.7%) was revised for management of infection. Statistical analysis using Kaplan Meier curve showed 93.3% survival rate.

The only failure in our series occurred in a 58-year-old male patient; this patient had acetabular fracture, which was treated by open reduction and internal fixation at the age of 40 then primary THA for management post-traumatic arthritis of the hip joint at age 48. Subsequently the patient underwent revision THA for management of polyethylene wear (liner exchange) at age of 61 years. The patient was diagnosed with chronic infected THA 2 years following revision THA. Eventually, the patient had good result after single stage acetabular component exchange with preservation of the femoral component, but unfortunately the infection recurred after 14 mo. The patient was treated successfully with surgical intervention by removal of the acetabular fixation, irrigation, and debridement and liner exchange. Coagulase negative staphylococcus aureus was the infective organism at all the stages of management.

Two complications occurred in 2 patients. The first patient was 38-year female; the patient suffered from recurrent hip dislocation 12 years following the definitive procedure, this complication was managed by revision THA with abductor reconstruction and constrained acetabular liner, no clinical signs of infection were found during the revision procedure and no organism was grown from the intra-operative cultures. The second complication occurred in a 53-year-old female patient, the acetabular component was revised due to aseptic loosening 2 years following the definitive procedure. No evidence of infection was seen at the revision procedure (Table 2).

Infection after THA is a devastating complication; there is no randomized prospective study to evaluate the outcome of different management options. Two-stage exchange arthroplasty is generally felt to be the gold standard method of management. However, this strategy has some drawbacks; long duration of treatment, patient morbidity and high economic cost. The reported failure rates after two-stage hip revision range from 5% to 18%[6,17,18]. One stage revision is an attractive option for the management of infected hip arthroplasty, with a comparable reinfection rates to two stage exchange and higher functional outcome scores, reduce morbidity, and cost of the management[7,19-21].

The concept of single stage acetabular exchange arthroplasty with retention of well fixed femoral component in management of chronic infected total hip arthroplasty was brought into attention because removal of well fixed cement less femoral component is a complex procedure, which necessitates extensive soft tissue dissection and femoral osteotomies that can de-vascularize the proximal femur and may result in degradation of the bone stock, and significant post operative morbidity.

Bacterial adherence and subsequent biofilm formation on implant are involved in the origin and chronicity of implant-related infection. Different biomaterials are claimed to differently suffer from microorganism adherence and biofilm formation, justifying partial component exchange in some acute prosthetic joint infection. Experimental studies showed more adherences of microorganisms and formation of biofilm to rough surfaced Ti alloys than polished surfaces[22].

In a recent study, Gómez-Barrena et al[23] proved that sonification of retrieved implants after prosthetic joint infection showed almost no bacterial adherence to the polished femoral head components in total hip replacement, while knee infections basically seeded on the tibial trays with minimal seeding on the polished femoral component. Theoretically, a well fixed circumferentially ingrown cementless femoral stem can isolate the femoral canal from the infected joint fluid and prevent the formation of biofilm layer on the femoral stem. Therefore, there is high possibility to control infection without the need to remove the well fixed femoral component which seal the femoral canal from the infecting microorganisms.

Two recent reports demonstrate high success rate of two-stage partial exchange with retention of the well-fixed cement less femoral component. In the first report by Lee et al[24], 17 infected THA were managed by two stage exchange arthroplasty; in the first stage irrigation and debridement was done followed by removal of the acetabular components, the femoral component was retained and the exposed metal parts of the femoral stem and femoral head was covered by antibiotic loaded bone cement. The acetabulum was reconstructed in the second stage. At mean follow-up of 4 years, 15 of the 17 (88%) demonstrated no recurrence of infection[24]. The second report by Ekpo et al[25], reported 19 infected hips treated with two stage partial exchange with retention of the well-fixed cement less femoral component. At mean follow-up of 4 years, 17 of the 19 (89%) demonstrated no recurrence of infection[25].

The Exeter group reported their outcome of management of infected cemented (THA) by two-stage exchange with preservation of the original femoral cement mantle. The hypothesis was that Osteointegrated cement-bone interface is not part of the effective joint space and is inaccessible to infecting organisms. Fifteen patients were treated with two-stage exchange with retention of the well-fixed cement mantle; infection was controlled in 14 patients at mean follow-up of 82 mo[16].

The main purpose of this study was to evaluate the success of single stage acetabular component exchange with retention of well-fixed femoral component. To our knowledge, this is the first report evaluating the results of this procedure.

From January 1997 to January 2012, the senior author performed 600-revision Total hip arthroplasty for various reasons, 92 of them were two-stage exchange for infected Total Hip arthroplasty. Single stage exchange with retention of well-fixed acetabular component was performed in 15 cases which represent (14%) of the cases treated for management of infected Total hip arthroplasty.

We defined failure by recurrence of infection that requires either surgical intervention or chronic suppressive antibiotics. Our infection recurrence rate was 6.7% at mean follow-up of 102.8 mo. The results compare favourably with previously published data of two-stage exchange[6,7,11,17,20-25]. We are comparing the success of the procedure to two-stage exchange arthroplasty as it is considered the gold standard management option of such problem.

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was a retrospective, which can introduce the possibility of selection bias. Second, because of the small number of the patients we could not further analyze data stratifying for virulence of the organism, type of infection, and duration of infection. However, 15 patients treated with this technique for management of infected total hip arthroplasty reflect that strict selection protocol was applied to use this method of treatment and reflect that we are considering this technique when specific criteria are met. Different treatment modalities were utilized when these specific selection criteria for single stage, single component revision were not met. The infecting organism was not identified in one patient prior to the surgery, which raises the possibility that these patients might be infected with virulent microorganisms but in the meantime these patients met all other inclusion criteria. Finally, functional outcomes were not recorded in this study because of the retrospective nature of the study, but we believe that success of eradication of infection is a strong predictor of functional improvement.

In conclusion, our results of management of infected THA with single stage acetabular component exchange with retention of a well-fixed femoral component is encouraging and showed low risk of future recurrence. Retention of the femoral component preserves the femoral bone stock, decreases patients’ morbidity, and lessens reconstructive complexity at the time of the revision. Based on our results, success can be achieved with this technique when the following criteria are met: (1) well-fixed femoral component; (2) good patient general health; (3) no draining sinuses; and (4) sensitive microorganisms isolated.

We are not proposing this method of treatment as alternative tool to two stage exchange for management of infected Total hip arthroplasty but it should be considered as one of the management options for treatment of this problem provided strict selection criteria are met. Further randomized controlled trial and trials with large volume of patients is needed to validate the best treatment option.

Peri-prosthetic hip infection is a devastating complication: The authors hypothesized that a well-fixed circumferentially ingrown cement-less stem can act as a shield and prevent the spread of pathogens and formation of biofilm around the body of the femoral stem. Therefore, single stage exchange of the acetabular component with retention of the well-fixed femoral component can be a successful option in management of infected total hip arthroplasty, when the following criteria are met; well-fixed femoral component, no draining sinuses, non immune compromised patients, and infection with sensitive organisms.

Preservation of well fixed cementless femoral component in infected total hip arthroplasty cases will decrease the morbidity of management infected total hip arthroplasty patients. This is the only report in their literature up to the authors’ knowledge presenting this technique. This study presents long term results of this procedure.

Most of the papers in the literature present results about either one stage or two stage exchange in management of infected total hip arthroplasty. The authors present a very good success rate of our procedure in management of selected patients with infected total hip arthoplasty. The authors’ protocol of management can be added to the treatment option of infected total hip arthroplasty.

This article will encourage other surgeons either to use this technique or present their work if using similar technique in management of infected hip narthroplasty, this can lead to increase the credibility of using single stage exchange with preservation of well fixed femoral stem in management of infected total hip arthroplasty if selected criteria were met.

THA: Total hip arthroplasty; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBC: White blood cell count; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologist.

This paper gives readers one of the management options for treatment of infected total hip arthroplasty provided strict selection criteria are met. The manuscript is suitable for the readers.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Buttaro MA, Cui Q, Hasegawa M, Huang TW S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Macheras GA, Koutsostathis SD, Kateros K, Papadakis S, Anastasopoulos P. A two stage re-implantation protocol for the treatment of deep periprosthetic hip infection. Mid to long-term results. Hip Int. 2012;22 Suppl 8:S54-S61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bozic KJ, Ries MD. The impact of infection after total hip arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1746-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sanchez-Sotelo J, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD, Cabanela ME. Midterm to long-term followup of staged reimplantation for infected hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:219-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Spangehl MJ, Younger AS, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Diagnosis of infection following total hip arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:285-295. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lieberman JR, Callaway GH, Salvati EA, Pellicci PM, Brause BD. Treatment of the infected total hip arthroplasty with a two-stage reimplantation protocol. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;205-212. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Masri BA, Panagiotopoulos KP, Greidanus NV, Garbuz DS, Duncan CP. Cementless two-stage exchange arthroplasty for infection after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:72-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beswick AD, Elvers KT, Smith AJ, Gooberman-Hill R, Lovering A, Blom AW. What is the evidence base to guide surgical treatment of infected hip prostheses? systematic review of longitudinal studies in unselected patients. BMC Med. 2012;10:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Buchholz HW, Elson RA, Engelbrecht E, Lodenkämper H, Röttger J, Siegel A. Management of deep infection of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63-B:342-353. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ure KJ, Amstutz HC, Nasser S, Schmalzried TP. Direct-exchange arthroplasty for the treatment of infection after total hip replacement. An average ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:961-968. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Garvin KL, Fitzgerald RH, Salvati EA, Brause BD, Nercessian OA, Wallrichs SL, Ilstrup DM. Reconstruction of the infected total hip and knee arthroplasty with gentamicin-impregnated Palacos bone cement. Instr Course Lect. 1993;42:293-302. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hsieh PH, Shih CH, Chang YH, Lee MS, Yang WE, Shih HN. Treatment of deep infection of the hip associated with massive bone loss: two-stage revision with an antibiotic-loaded interim cement prosthesis followed by reconstruction with allograft. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:770-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Winkler H. Bone grafting and one-stage revision of THR - biological reconstruction and effective antimicrobial treatment using antibiotic impregnated allograft bone. Hip Int. 2012;22 Suppl 8:S62-S68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fisman DN, Reilly DT, Karchmer AW, Goldie SJ. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 2 management strategies for infected total hip arthroplasty in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:419-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sukeik M, Patel S, Haddad FS. Aggressive early débridement for treatment of acutely infected cemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:3164-3170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gehrke T, Kendoff D. Peri-prosthetic hip infections: in favour of one-stage. Hip Int. 2012;22 Suppl 8:S40-S45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Morley JR, Blake SM, Hubble MJ, Timperley AJ, Gie GA, Howell JR. Preservation of the original femoral cement mantle during the management of infected cemented total hip replacement by two-stage revision. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leung F, Richards CJ, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Two-stage total hip arthroplasty: how often does it control methicillin-resistant infection? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1009-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sorlí L, Puig L, Torres-Claramunt R, González A, Alier A, Knobel H, Salvadó M, Horcajada JP. The relationship between microbiology results in the second of a two-stage exchange procedure using cement spacers and the outcome after revision total joint replacement for infection: the use of sonication to aid bacteriological analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:249-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yoo JJ, Kwon YS, Koo KH, Yoon KS, Kim YM, Kim HJ. One-stage cementless revision arthroplasty for infected hip replacements. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1195-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lange J, Troelsen A, Thomsen RW, Søballe K. Chronic infections in hip arthroplasties: comparing risk of reinfection following one-stage and two-stage revision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:57-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Leonard HA, Liddle AD, Burke O, Murray DW, Pandit H. Single- or two-stage revision for infected total hip arthroplasty? A systematic review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1036-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Costerton JW. Biofilm theory can guide the treatment of device-related orthopaedic infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;7-11. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Gómez-Barrena E, Esteban J, Medel F, Molina-Manso D, Ortiz-Pérez A, Cordero-Ampuero J, Puértolas JA. Bacterial adherence to separated modular components in joint prosthesis: a clinical study. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:1634-1639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lee YK, Lee KH, Nho JH, Ha YC, Koo KH. Retaining well-fixed cementless stem in the treatment of infected hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2013;84:260-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ekpo TE, Berend KR, Morris MJ, Adams JB, Lombardi AV. Partial two-stage exchange for infected total hip arthroplasty: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:437-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |