Published online Feb 18, 2017. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i2.163

Peer-review started: July 21, 2016

First decision: September 5, 2016

Revised: October 31, 2016

Accepted: November 21, 2016

Article in press: November 23, 2016

Published online: February 18, 2017

Processing time: 210 Days and 14.4 Hours

To investigate the effectiveness of ultrasound-guided release of the first annular pulley and compare results with the conventional open operative technique.

In this prospective randomized, single-center, clinical study, 32 patients with trigger finger or trigger thumb, grade II-IV according to Green classification system, were recruited. Two groups were formed; Group A (16 patients) was treated with an ultrasound-guided percutaneous release of the affected A1 pulley under local anesthesia. Group B (16 patients) underwent an open surgical release of the A1 pulley, through a 10-15 mm incision. Patients were assessed pre- and postoperatively (follow-up: 2, 4 and 12 wk) by physicians blinded to the procedures. Treatment of triggering (primary variable of interest) was expressed as the “success rate” per digit. The time for taking postoperative pain killers, range of motion recovery, QuickDASH test scores (Greek version), return to normal activities (including work), complications and cosmetic results were assessed.

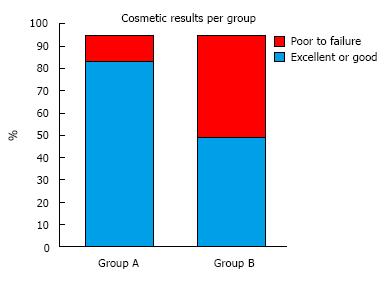

The success rate in group A was 93.75% (15/16) and in group B 100% (16/16). Mean times in group A patients were 3.5 d for taking pain killers, 4.1 d for returning to normal activities, and 7.2 and 3.9 d for complete extension and flexion recovery, respectively. Mean QuickDASH scores in group A were 45.5 preoperatively and, 7.5, 0.5 and 0 after 2, 4, and 12 wk postoperatively. Mean times in group B patients were 2.9 d for taking pain killers, 17.8 d for returning to normal activities, and 5.6 and 3 d for complete extension and flexion recovery. Mean QuickDASH scores in group B were 43.2 preoperatively and, 8.2, 1.3 and 0 after 2, 4, and 12 wk postoperatively. The cosmetic results found excellent or good in 87.5% (14/16) of group A patients, while in 56.25% (9/16) of group B patients were evaluated as fair or poor.

Treatment of the trigger finger using ultrasonography resulted in fewer absence of work days, and better cosmetic results, in comparison with the open surgery technique. It is a promising method that represents excellent results without major complications, so that it could be possibly be established as a first-line treatment in the trigger finger’s disease.

Core tip: In this randomized, prospective clinical trial, of 32 patients with trigger finger or trigger thumb, ultrasound assisted treatment of the A1 pulley, revealed better outcome in comparison with the open technique. Patients had fewer work absence days and improved surgical scar. To the best of our knowledge this is the first randomized trial in this field. These promising results have to be further confirmed with larger trials in the future.

- Citation: Nikolaou VS, Malahias MA, Kaseta MK, Sourlas I, Babis GC. Comparative clinical study of ultrasound-guided A1 pulley release vs open surgical intervention in the treatment of trigger finger. World J Orthop 2017; 8(2): 163-169

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v8/i2/163.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v8.i2.163

Stenosing tenosynovitis with mechanical impingement of the flexor tendons at the A1 pulley is a common condition affecting the digits in the following order of decreasing prevalence: Thumb, ring, middle, small and index. A nodule or thickening in the flexor tendon becomes trapped proximal to the pulley, making finger extension difficult.

There have been described several management approaches in the treatment of trigger finger disease. Nonsurgical management includes corticosteroid injection and splinting. However, according to a a level I systematic review[1] corticosteroid injections are effective in just 57% of patients. Additionally, that technique can result in up to 29% recurrence[2]. Furthermore, many patients treated by conservative means, like immobilization or injections, may additionally require surgery[3]. In a recent clinical trial, designed to compare the effectiveness of 2 splint designs in treating trigger finger[4], the results showed positive outcomes in 50%-77% of the patients, depending on the type of splinting.

On the other hand, many authors support the superiority of surgical procedures for the definite treatment of the disease[5]. Indeed, the percutaneous and open surgery methods have been proved more efficient than simple corticosteroid injection, regarding the cure and relapse of the disease[5,6]. Conventional open surgical technique remains the gold standard of treatment options[7]. However, surgical treatment also has complications, including scarring, surgical site infections and nerve injuries, in addition to possible disease relapse[8].

Percutaneous surgical release of trigger finger is a preferable alternative to open surgery[9], although a potential disadvantage can be the injury to either nerve or tendon due to the limited visibility[7]. Many hand surgeons avoid this treatment option due to the close proximity to the digital nerve[10]. According to a meta-analysis of current literature[11], blind percutaneous release has become more and more popular lately, with overall increased success rates.

Ultrasound can be a helpful tool for better success by means of assisting the placement of the the needle during percutaneous procedure[12]. There is a controversy regarding the safety and usefulness of this technique. Paulius et al[13] showed that ultrasound-guided treatment has disadvantages like tendon injuries, neural or vascular lacerations and no complete release of the first annular pulleys. As an answer to them, Wu et al[14] support the usage of ultrasound assistence to avoid iatrogenic damage.

In a recent systematic review of current evidence, it is revealed that percutaneous release with ultrasonography, resulted in higher success rate than non-sonography release[11]. Despite that, till now, no randomized controlled trials could be found at the Medline and Cochrane Database, comparing open surgery to ultasound-guided percutaneous release.

This lack of reliable trials comparing open surgery to ultrasound-guided A1 pulley release is pronounced. In the present randomized controlled trial, we tried to compare the efficacy of a single ultrasound-guided percutaneous A1 pulley release with conventional open surgery in terms of ability to correct the trigger finger.

We conducted a randomized, prospective, controlled, single-center, clinical trial of 32 patients with resistant - after conservative treatment - trigger finger or trigger thumb, suffering at least for 3 mo. The majority of the patients were middle-aged women (62.5% females, mean age: 45.5 years old), evaluated as grade II to IV according to Green classification system of the trigger finger disease.

We excluded patients under 18 years old, these who were treated with a previous operation or a corticosteroid injection for their disease and those who were suffering by inflammatory arthritis, tumor or autoimmune disease. Moreover, we did not include patients with multiple trigger fingers trying to evaluate our study groups strictly using the model one patient-one trigger finger. We did not exclude patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and a history of other tendon related pathology of the upper extremity, although it is known that they might be linked with a higher rate of treatment failure[15].

The patients were clinically and ultrasonographically examined and then they were randomly divided into two groups using a closed envelope. The ultrasonography was performed with a portable grey scale ultrasound (frequency of 10-12 MHz, 5-12 MHz, Linear Array, A6 Portable Ultrasonic Diagnostic System, Sonoscape Company Limited, Shenzhen, China) by a doctor of our department. The patients were informed with an oral and written manner for their options of treatment and they received clear explanations about their suggested treatment. For confirmation, they signed full written consent.

Group A (16 patients) was treated with an ultrasound-guided percutaneous release of the affected first annular pulley under local anesthesia and without any corticosteroid injection.

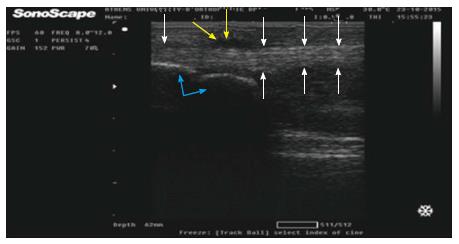

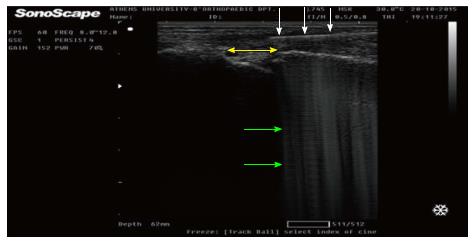

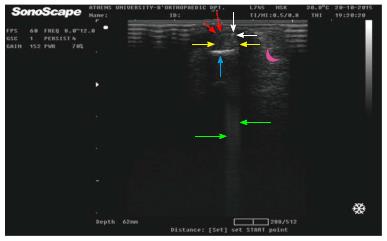

In addition, group B (16 patients) underwent a conventional open surgical release of the A1 pulley, through a 10-15 mm incision. The technique in group A included initially a sonographically guided local anesthetic injection, proximally to the metacarpal-phalangeal joint (Figure 1). The infiltration was done under sterile conditions (sterilization of the skin, coverage of the ultrasound probe with sterile pad, use of appropriate gel) by a physician that simultaneously managed the ultrasound device (one man’s technique). Under continuous sonographic imaging of the digital neurovascular structures, the physician inserted percutaneously - through a negligible section < 1 mm - an ophthalmic corneal/scleral V-Lance knife (Alcon, Novartis company), over flexor tendons (Verdan’s zone 3, proximally to the A1 pulley) and towards their longitudinal axis (Figure 2). Then, the knife was advanced distally, just below A1 pulley (Figure 3) and pressed palmary so as to loosen the thicken pulley (the intersecting part).

Thus, after having withdrawn the V-Lance knife (which had created the necessary space intrasheath), a thin hook with a long neck was introduced under the - now extended - A1 pulley (Figure 4). The hook penetrated the annular ligamentous structure facing palmary in order to protect the flexor tendons and subsequently removed proximally (in a steady quick move) carrying along and dissecting the A1 pulley. Intraoperatively and right after the performed dissection, each patient was clinically and sonographically evaluated for the achieved resolution of the triggering.

All patients were estimated with the completion of Q-DASH score before and after the operation (1, 4, 12 wk). Resolution of triggering (primary variable of interest) was expressed as the “success rate” per digit. The time for taking postoperative pain killers, range of motion recovery, return to normal activities (including work), complications and cosmetic results were assessed. Differences among groups were analysed using Students t test. Statistical significant difference was considered if P < 0.05.

The same doctor did the procedure in all patients (Group A and Group B) and evaluated them prior to the injection through Q-DASH questionnaire, clinical and ultrasound examination. Another doctor evaluated the patients in the follow-up period. This physician was blinded to the procedure (ultrasound-guided or open) and to the pre-injection scores of these patients as far as Q-DASH, resolution of triggering, painkillers and return to normal activities, but he was non blinded as far cosmetic results, range of motion and complications. Instructions for return to work (or usual activities in elderly people) were different in group A patients than in group B. We were able to be more aggressive with group A patients which we advised to start their work from the first postoperative day. On the contrary, group B patients could not be managed to start working before removing their sutures (12-14 d).

Our study protocol (plus our written consent form) was approved by our Health’s Institution Scientific Committee and the Athens University, School of Medicine.

We were able to visualize the flexor tendons under the A1 pulley and recognise the digital neurovascular bundles in all group A patients. The whole percutaneous procedure was real-time documented and there was no mentioned intraoperative complication in anyone of our patients.

We managed to obtain follow-up in 100% (32 out of 32) of our patients. The success rate in group A was 93.75% (15/16) and in group B 100% (16/16) (P > 0.05). There was just one patient (female, 53 years old, white collar worker, with uncontrolled hypothyroeidism, index finger) who appeared to have no improvement in her triggering after the percutaneous ultrasound-guided procedure. Apart from this exception, both techniques proved to be well tolerated, with no side effects, infections or complaints for persistent pain.

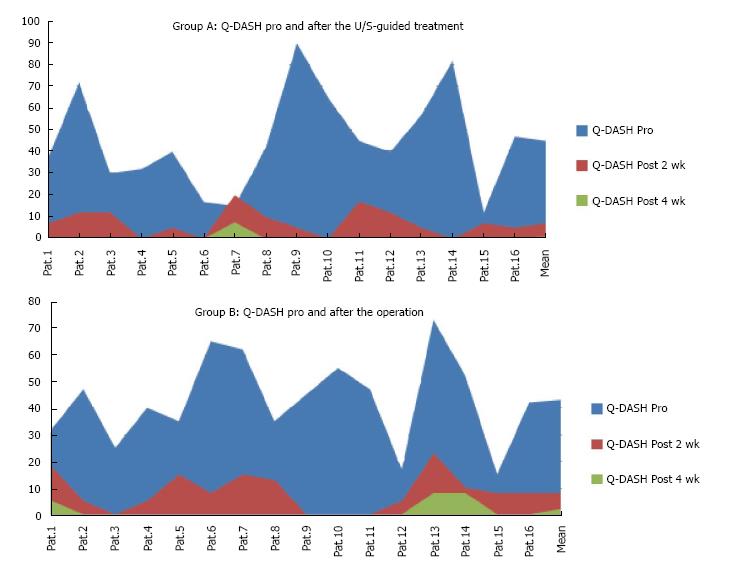

Mean times in group A patients were 3.5 d for taking pain killers, and 7.2 and 3.9 d for complete extension and flexion recovery, respectively (Table 1). Mean Quick DASH scores in group A were 45.5 preoperatively and, 7.5, 0.5 and 0 after 2, 4, and 12 wk postoperatively (Figure 5A).

| Group A | Post painkillers (d) | Return to normal (d) | Full extension (d) | Full flexion (d) |

| Patient 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 4 |

| Patient 2 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 5 |

| Patient 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Patient 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| Patient 5 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| Patient 6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Patient 7 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 6 |

| Patient 8 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 7 |

| Patient 9 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Patient 10 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| Patient 11 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 7 |

| Patient 12 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Patient 13 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Patient 14 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 5 |

| Patient 15 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 5 |

| Patient 16 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 6 |

| Total | 56 | 65 | 115 | 63 |

| Mean | 3.5 | 4.1 | 7.2 | 3.9 |

Mean times in group B patients were 2.9 d for taking pain killers, and 5.6 and 3 d for complete extension and flexion recovery (Table 2). Mean QuickDASH scores in group B were 43.2 preoperatively and, 8.2, 1.3 and 0 after 2, 4, and 12 wk postoperatively (Figure 5B). These differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05) among the two groups.

| Group B | Post painkillers (d) | Return to normal (d) | Full extension (d) | Full flexion (d) |

| Patients 1 | 5 | 23 | 7 | 3 |

| Patients 2 | 0 | 15 | 5 | 4 |

| Patients 3 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| Patients 4 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| Patients 5 | 3 | 17 | 11 | 4 |

| Patients 6 | 3 | 15 | 4 | 3 |

| Patients 7 | 4 | 21 | 8 | 4 |

| Patients 8 | 6 | 22 | 9 | 5 |

| Patients 9 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| Patients 10 | 2 | 18 | 6 | 3 |

| Patients 11 | 5 | 18 | 6 | 5 |

| Patients 12 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 2 |

| Patients 13 | 6 | 23 | 16 | 3 |

| Patients 14 | 4 | 22 | 4 | 3 |

| Patients 15 | 3 | 17 | 2 | 4 |

| Patients 16 | 1 | 15 | 5 | 2 |

| Total | 46 | 285 | 90 | 48 |

| Mean | 2.9 | 17.8 | 5.6 | 3 |

However, mean time for returning to normal activities in group A patients was 4.1 d as opposite to 17.8 d for Group B patients (P < 0.05).

Additionally, the cosmetic results found excellent or good in 87.5% (14/16) of group A patients, while in 56.25% (9/16) of group B patients were evaluated as fair or poor (P < 0.05) (Figure 6).

According to the literature, there is an emerging number of cadaveric and clinical studies investigating the use of ultrasound in hand and wrist tendinopathies[15-17]. Especially in the trigger finger disease we were able to find a wide variety of anatomic or therapeutic trials[18-20].

Ultrasound examination can diagnose secondary causes of trigger fingering[21], while it could be a valuable tool in guiding therapeutic procedures. However, it can demand extra time and effort and the potential clinical benefits compared to the blind technique can be questionable[22].

According to Rojo-Manaute et al[23], good knowledge of the anatomy, and excellent handling of the ultrasound machine, can result to safe and successfull treatment of the trigger finger. Thus, offering an alternative to traditional open surgery. This specific procedure can be performed in the medical office with the use of a portable ultrasound device for the purpose of improving the cost-effectiveness of the treatment and reducing the surgery-related anxiety of patients. Furthermore, this technique promises to minimize postoperative short-term morbidity[24].

Rajeswaran et al[25] described an ultrasound-guided procedure using a modified hypodermic needle to resolve trigger finger. He documented no complications and a complete resolution of triggering in 91% of his patients[25]. Besides, using a knife result in a complete pulley release significantly better compared to the needle technique[26]. On the other hand, in an experimental cadaveric study, ultrasound-guided percutaneous A1 pulley release resulted in repeated injuries of the tendon sheath and of the proximal neural or vascular structures[13].

Finally, in the most recent study, Lapègue et al[27] conclude that US-guided treatment of the trigger finger is feasible in current practice, with minimal complications, even if their trial showed a 17% postoperative persistance of triggering.

In our study we aimed to prove that an ultrasound assisted release of the A1 pulley is - at least - not inferior than the open technique in a matched controlled population, regarding the clinical outcome scores. Strong points of our trial are that as far as we know, this is the first prospective randomized trial publishedin the English speaking literature. We have used different qualitative and quantitative scales to document our results. Apropos of indexes like Q-DASH, resolution of triggering, painkillers and return to normal activities, the follow-up of our patients was blinded.

Limitations of this study also merrit to be mentioned. Statistical power is reduced due to the small sample size in the present study (n = 32). This could have played a role in reducing the significance of some of the statistical tests. A post hoc power analysis, using the GPower software (Faul and Erdfelder, 1992) showed that on the basis of the means, among groups, an n of approximately 60 (30 in each group) would be needed to give better statistical power at the recommended 0.80 level. Additionally, We had only short- to mid-term results in the follow-up of our patients but at the other end of the spectrum this seems to be the usual postoperative protocol according to the literature[28]. Another weakness of our study is that it was not as cost-effective as it could be. That was because we avoided treating our ultrasound-guided patients at the medical office but exclusively in the operative theater in order to eradicate extrinsic factors between the two groups.

Our study revealed that ultrasound assisted release of the A1 pulley resulted in less days of work absence and better cosmetic results, in comparison with the traditional open technique. Notwithstanding, it is necessary more clinical trials to be followed through on this area of interest in order to obtain more secure conclusions.

The authors would like to thank the “Konstantopouleio” General Hospital’s nurse personnel working at the operating theater used in our trial (especially Mrs. Remoundou Maria and Mrs. Ioannou Aikaterini), for their valuable assistance to the clinical part of our study.

Stenosing tenosynovitis with mechanical impingement of the flexor tendons at the A1 pulley is a common condition affecting the digits in the following order of decreasing prevalence: Thumb, ring, middle, small and index. A nodule or thickening in the flexor tendon becomes trapped proximal to the pulley, making finger extension difficult. There have been described several management approaches in the treatment of trigger finger disease. Surgery is recommended in those cases that conservative treatment has failed. Conventional open surgical technique remains the gold standard of treatment. However, complications do exist, such as painful scarring, infections and nerve damage, in addition to recurrence of the disease.

In a recent systematic review of current evidence, it is revealed that percutaneous release with sonography guidance had a significantly higher success rate than non-sonography guidance. Despite that, no randomized controlled trials exists comparing open surgery to ultrasound-guided percutaneous release. In the present randomized controlled trial, they compared the efficacy of a single ultrasound-guided percutaneous A1 pulley release with conventional open surgery in terms of ability to correct the trigger finger. To the best of our knowledge this is the first randomized trial in this field.

Ultrasound-guided release of the A1 pulley yielded better results compared to the traditional open technique, in respect to fewer working days lost and improved cosmetic results. It is a promising method that produces excellent results without major complications, so that it could be possibly be established as a first-line treatment in the trigger finger’s disease. However, in order to be established as a first-line treatment in the trigger finger’s disease, it is necessary more clinical trials to be followed through on this area of interest.

Trigger finger: Stenosing tenosynovitis with mechanical impingement of the flexor tendons at the A1 pulley. Condition affects the digits in the following order of decreasing prevalence: Thumb, ring, middle, small and index. A nodule or thickening in the flexor tendon becomes trapped proximal to the pulley, making finger extension difficult.

This manuscript investigated the usefulness of ultrasonography for the surgical treatment of finger.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ciccone MM, Tomizawa M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Fleisch SB, Spindler KP, Lee DH. Corticosteroid injections in the treatment of trigger finger: a level I and II systematic review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:166-171. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rhoades CE, Gelberman RH, Manjarris JF. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the fingers and thumb. Results of a prospective trial of steroid injection and splinting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;236-238. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Benson LS, Ptaszek AJ. Injection versus surgery in the treatment of trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tarbhai K, Hannah S, von Schroeder HP. Trigger finger treatment: a comparison of 2 splint designs. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:243-249, 249.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang J, Zhao JG, Liang CC. Percutaneous release, open surgery, or corticosteroid injection, which is the best treatment method for trigger digits? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1879-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sato ES, Gomes Dos Santos JB, Belloti JC, Albertoni WM, Faloppa F. Treatment of trigger finger: randomized clinical trial comparing the methods of corticosteroid injection, percutaneous release and open surgery. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Guler F, Kose O, Ercan EC, Turan A, Canbora K. Open versus percutaneous release for the treatment of trigger thumb. Orthopedics. 2013;36:e1290-e1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Turowski GA, Zdankiewicz PD, Thomson JG. The results of surgical treatment of trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:145-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Uçar BY. Percutaneous surgery: a safe procedure for trigger finger? N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4:401-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Uras I, Yavuz O. Percutaneous release of trigger thumb: do we really need steroid? Int Orthop. 2007;31:577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhao JG, Kan SL, Zhao L, Wang ZL, Long L, Wang J, Liang CC. Percutaneous first annular pulley release for trigger digits: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current evidence. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:2192-2202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jou IM, Chern TC. Sonographically assisted percutaneous release of the a1 pulley: a new surgical technique for treating trigger digit. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:191-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Paulius KL, Maguina P. Ultrasound-assisted percutaneous trigger finger release: is it safe? Hand (N Y). 2009;4:35-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu KC, Chern TC, Jou IM. Ultrasound-assisted percutaneous trigger finger release: it is safe. Hand (N Y). 2009;4:339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chan JK, Choa RM, Chung D, Sleat G, Warwick R, Smith GD. High resolution ultrasonography of the hand and wrist: three-year experience at a District General Hospital Trust. Hand Surg. 2010;15:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Draghi F, Bortolotto C. Intersection syndrome: ultrasound imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:283-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sato J, Ishii Y, Noguchi H, Takeda M. Sonographic analyses of pulley and flexor tendon in idiopathic trigger finger with interphalangeal joint contracture. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:1146-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yang TH, Lin YH, Chuang BI, Chen HC, Lin WJ, Yang DS, Wang SH, Sun YN, Jou IM, Kuo LC. Identification of the Position and Thickness of the First Annular Pulley in Sonographic Images. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:1075-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim SJ, Lee CH, Choi WS, Lee BG, Kim JH, Lee KH. The thickness of the A2 pulley and the flexor tendon are related to the severity of trigger finger: results of a prospective study using high-resolution ultrasonography. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016;41:204-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sato J, Ishii Y, Noguchi H, Takeda M. Sonographic appearance of the flexor tendon, volar plate, and A1 pulley with respect to the severity of trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:2012-2020. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kara M, Ekiz T, Sumer HG. Hand pain and trigger finger due to ganglion cyst: an ultrasound-guided diagnosis and injection. Pain Physician. 2014;17:E786. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Cecen GS, Gulabi D, Saglam F, Tanju NU, Bekler HI. Corticosteroid injection for trigger finger: blinded or ultrasound-guided injection? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:125-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rojo-Manaute JM, Rodríguez-Maruri G, Capa-Grasa A, Chana-Rodríguez F, Soto Mdel V, Martín JV. Sonographically guided intrasheath percutaneous release of the first annular pulley for trigger digits, part 1: clinical efficacy and safety. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:417-424. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Hopkins J, Sampson M. Percutaneous tenotomy: Development of a novel, percutaneous, ultrasound-guided needle-cutting technique for division of tendons and other connective tissue structures. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2014;58:327-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rajeswaran G, Lee JC, Eckersley R, Katsarma E, Healy JC. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous release of the annular pulley in trigger digit. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:2232-2237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Smith J, Rizzo M, Lai JK. Sonographically guided percutaneous first annular pulley release: cadaveric safety study of needle and knife techniques. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:1531-1542. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Lapègue F, André A, Meyrignac O, Pasquier-Bernachot E, Dupré P, Brun C, Bakouche S, Chiavassa-Gandois H, Sans N, Faruch M. US-guided Percutaneous Release of the Trigger Finger by Using a 21-gauge Needle: A Prospective Study of 60 Cases. Radiology. 2016;280:493-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jongjirasiri Y. The results of percutaneous release of trigger digits by using full handle knife 15 degrees: an anatomical hand surface landmark and clinical study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:1348-1355. [PubMed] |