Published online Aug 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i8.494

Peer-review started: February 25, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: May 13, 2016

Accepted: June 1, 2016

Article in press: June 3, 2016

Published online: August 18, 2016

Processing time: 176 Days and 4.2 Hours

AIM: To confirm the rarity of this disorder and then to evaluate the effects of antibiotic treatment alone and assess whether this could produce a complete remission of symptoms in children and adolescents.

METHODS: We made a retrospective review of all cases of condensing osteitis of the clavicle in children and adolescents between January 2007 and January 2016. Outpatient and inpatient medical records, with radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging, triphasic bone scan and computed tomography scans were retrospectively reviewed. All the patients underwent biopsy of the affected clavicle and were treated with intra venous (IV) antibiotics followed by oral antibiotics.

RESULTS: Seven cases of condensing osteitis of the clavicle were identified. All the patients presented with swelling of the medial end of the clavicle, and 5 out of 7 reported persisting pain. The patients’ mean age at presentation was 11.5 years (range 10.5-13). Biopsy confirmed the diagnosis in all cases. All the patients completed the treatment with IV and oral antibiotics. At last follow-up visit none of the patients complained of residual pain; all had a clinically evident reduction in the swelling of the medial end of the affected clavicle. The mean follow-up was 4 years (range 2-7).

CONCLUSION: Our findings show that condensing osteitis of the clavicle is a rare condition. Biopsy is needed to confirm diagnosis. The condition should be managed with IV and oral antibiotics. Aggressive surgery should be avoided.

Core tip: Condensing osteitis of the clavicle is a rare benign disorder. It is characterized by pain and swelling at the medial end of the clavicle, with increased radio-density. Neither the etiology of this rare condition nor its treatment options are completely clarified. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle in children and adolescents should be recognized promptly. Biopsy is needed to confirm diagnosis. Once diagnosis is made, the condition should be treated by parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy, and aggressive surgery should be avoided.

- Citation: Andreacchio A, Marengo L, Canavese F. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle in children. World J Orthop 2016; 7(8): 494-500

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i8/494.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i8.494

Brower et al[1] first described condensing osteitis of the clavicle in 1974. The condition was originally described as a syndrome causing pain and swelling over the medial end of the clavicle with increased radiographic density (sclerosis).

Since its first description, few cases of this condition have been described in the English-language literature[2-6]. Some authors consider it as an infective disease - a low-grade chronic osteomyelitis - while others suggest it could be a benign neoplastic process[4,7-9]. However, the etiology of this condition and its best treatment options still remain to be determined[2,5,7,10,11].

Although some cases of spontaneous remission have been observed, the disease often requires treatment. Conservative and surgical options have been described. A number of other different treatments have been recommended over the years, including antibiotic treatment, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, injection of corticosteroids or surgical resection of the medial end of the clavicle in refractory cases[4-6]. However, the etiology of this rare condition and its best form of treatment are still unknown[2,4,11-14].

This study set out to confirm the rarity of this pathology and to assess the outcome of patients treated by parenteral [intra venous (IV)] and oral antibiotic therapy. A review of the literature was also made.

We made a retrospective review of the archive of clinical records identifying all cases of condensing osteitis of the clavicle diagnosed at our children’s hospital from January 2007 to January 2016. Informed consent was obtained. Outpatient and inpatient medical records were reviewed, and we collected the following information for each of the patients: Sex, age at time of diagnosis, side involved, symptomatic picture at presentation, blood tests, type and length of antibiotic therapy, complications and outcome (Table 1).

| Patient | Age (yr) | Side | Gender | Symptoms | Biopsy | Antibiotic 1 | Antibiotic 2 | Evolution | Complications |

| 1 | 10.5 | Right | Male | Pain and discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint Swelling | Yes | Teicoplanin Rifampin 8 wk | Remission | - | |

| 2 | 11.2 | Right | Male | Pain and discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint Swelling | Yes | Teicoplanic Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 17 d | Rifampin Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 13 d | Remission | - |

| 3 | 11.2 | Right | Male | Pain and discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint Swelling | Yes | Teicoplanic Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 17 d | Rifampin Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 13 d | Remission | - |

| 4 | 12.1 | Right | Female | Pain and discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint Swelling | Yes | Teicoplanic Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 17 d | Rifampin Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 13 d | Remission | - |

| 5 | 12.4 | Right | Male | Pain and discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint Swelling | Yes | Teicoplanin Rifampin 8 wk | Remission | - | |

| 6 | 11.5 | Right | Female | Swelling | Yes | Teicoplanin Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 13 d | Azitromycin 5 d Rifampin Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 10 wk | Remission | Adverse effect with Teicoplanin |

| 7 | 13 | Right | Male | Swelling | Yes | Teicoplanic Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 17 d | Rifampin Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 13 d | Recurrence of pain | - |

Standard antero-posterior (AP) radiographs of the clavicle, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), triphasic bone scan (TBS) and computed tomography (CT) scans were also retrospectively reviewed.

All the patients underwent biopsy of the affected clavicle.

A search of the Medline database from 1950 to 2016 was made to identify papers related to condensing osteitis of the clavicle in children, adolescents and adults.

As recommended by the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic reviews[15], a variety of search terms (‘‘condensing’’, ‘‘osteitis’’, ‘‘clavicle’’ and ‘‘children’’) were used, including a combination of index and free-text terms.

Abstracts were screened, and relevant full texts of articles retrieved for further review. Reference sections of papers were also scrutinized to identify additional literature. All levels of evidence were included.

We retrieved 23 studies reporting a total of 51 patients (52 clavicles) with condensing osteitis of the clavicle. A total of 58 patients (59 clavicles), including our cases, were identified (Table 2).

| Ref. | Number of cases | Symptoms |

| Brower et al[1] | 1 | Pain |

| Teates et al[12] | 2 | |

| Simpson[3,5-7,10] | 1 | Limited ROM |

| Duro[3,5-7,10] | 2 | |

| Appell et al[2] | 7 | |

| Weiner[3,5,10] | 1 | Pain |

| Franquet[3,5,10] | 2 | Pain (related to work) |

| Cone[3,5,10] | 1 | Pain (worsening) |

| Kruger et al[7] | 3 | Pain (mild to moderate) |

| Outwater et al[10] | 1 | Limited ROM |

| Stewart[3,5,10] | 1 | Pain (intermittent) |

| Jones et al[6] | 3 | Pain |

| Lissens et al[8] | 2 | |

| Greenspan et al[4] | 3 | |

| Vierboom et al[13] | 1 | Pain (worsening) |

| Latifi[3,5-7,10] | 1 | |

| Tait[3,5-7,10] | 1 | |

| Berthelot et al[3] | 2 | |

| Hsu et al[5] | 1 | |

| Rand et al[14] | 4 | Pain (intermittent) Discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint |

| Noonan et al[9] | 1 | Pain (chronic) |

| Sng et al[11] | 9 | Pain Discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint |

| Imran[3,5-7,10] | 1 (bilateral) | |

| Present study (2016) | 7 | Pain Discomfort in the sterno-clavicular joint |

| Total | 58 patients (59 clavicles) | |

Seven cases of condensing osteitis were identified during study period (Table 1). There were 5 girls and 2 boys. The mean age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 11.5 years (range 10.5-13 years). The right side was involved in all cases. All the patients presented with swelling of the medial end of the clavicle. Five out of 7 patients complained of pain worsened by finger pressure at the level of the sterno-clavicular joint.

The swelling was investigated in all the patients, with a standard AP radiograph of the affected clavicle, MRI and TBS. Five out of 7 patients also underwent a CT scan of the affected clavicle.

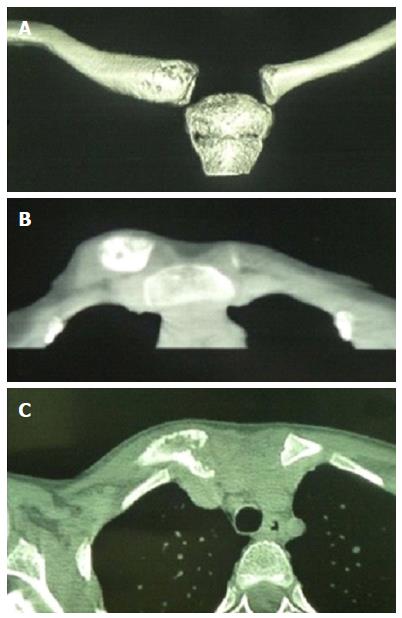

AP radiographs of the right clavicle (7/7 patients) showed expansion of the medial end of the clavicle, with signs of bone resorption and apposition in all cases (Figure 1).

MRI (7/7 patients) showed bone signal alterations of the medial end of the affected clavicle, and edema of the surrounding soft tissues in all cases.

CT scans (5/7 patients) showed expansion of the medial half of the clavicle with no evidence of infection or tumor in all cases (Figure 2).

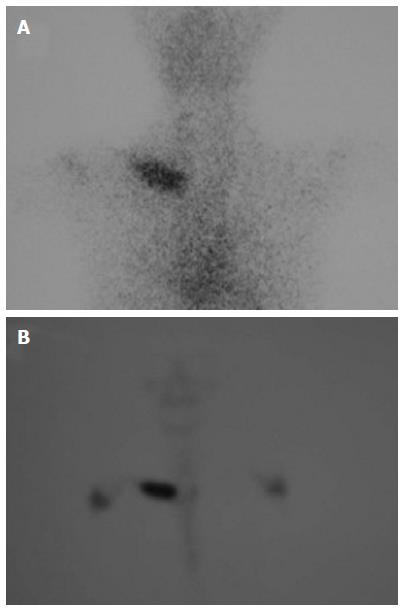

TBS (7/7 patients) was characterized by a strong hyperfixation of the medial half of the affected clavicle in all cases (Figure 3).

Results of blood tests, including inflammatory markers, were normal in all but 2 cases, in which C-reactive protein level was slightly increased (22.3 mg/dL), reverting to its normal range (< 10 mg/dL) after 4 d of IV antibiotic therapy.

All the patients underwent an incisional biopsy taken from the medial end of the affected clavicle for histology and cultures. Tissues cultures were negative, while histological results reflected a chronic inflammatory process in all the patients. These features were compatible with the diagnosis of condensing osteitis.

In agreement with Jones’ hypothesis of an infectious etiology[6], all the patients received teicoplanin (10 mg/kg every 12 h for a total of 3 doses, followed by 10 mg/kg every 24 h) combined with another type of antibiotic. Two patients received teicoplanin combined with rifampin (300 mg every 12 h) for 56 d. Five patients received teicoplanin combined with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (1 g every 6 h) for 17 d. The treatment choice was decided by the pediatric infectiologist.

At discharge, all the patients discontinued the IV treatment and started oral rifampin (600 mg every 24 h) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (80 mg + 200 mg every 12 h) for 13 d.

One patient developed an adverse drug reaction to teicoplanin after 13 d of treatment. The treatment with teicoplanin and amoxicillin was discontinued, and was replaced by azitromycin (300 mg every 12 h) for 5 d and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (680 mg + 97 mg every 8 h) for 70 d and rifampin (450 mg every 24 h) for 65 d.

All the patients responded well to antibiotic therapy, and showed complete remission of pain and an initial decrease in the swelling.

After 5 mo of therapy one patient experienced a recurrence of pain at the same site. The patient was treated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for 14 d with complete remission of symptoms.

The mean length of follow-up was 4 years (range 2-7). At last follow-up visit none of the patients complained of pain. All reported a significant remission of pain and a marked reduction in the swelling on the medial half of the affected clavicle.

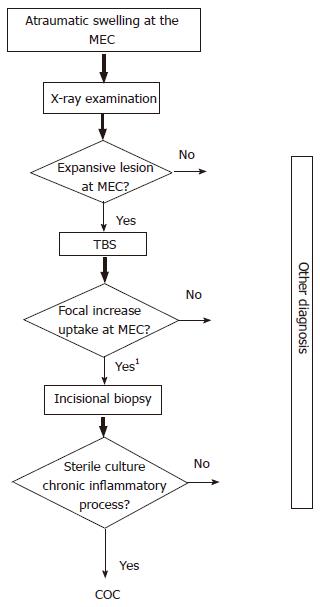

This study reviewed 7 skeletally immature patients with condensing osteitis of the clavicle. We found that an appropriate IV and oral antibiotic treatment could lead to a significant remission of signs and symptoms in children and adolescents with condensing osteitis of the clavicle (Figure 4).

Since its first description by Brower et al[1] in 1974, very few cases of condensing osteitis of the clavicle have been reported in the English-language literature (Table 2).

In 1991 Greenspan et al[4] highlighted the rarity of this condition and reported three new proven cases, to be added to the 13 previously reported. The first reported cases all occurred in middle-aged women. It was only in 1983 that Appell et al[2] observed this clinical feature at a pediatric age. Noonan et al[9] described the first male adult patient in 1998.

Although many etiopathogenetic hypotheses have been suggested for this disease, its exact cause still remains unknown. Originally, the condition was considered as a response to abnormal and repetitive mechanical stresses, such as might occur with the lifting of heavy loads. In the case of children and adolescents, this hypothesis might be linked to the carrying of a school backpack on a single brace[2].

However, in 1987, Kruger et al[7] described 3 women affected by condensing osteitis with no risk factor. One year later, Outwater and Oates[10] reviewed 11 cases with no history of direct trauma. They suggested that osteonecrosis might play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disorder, noting that devitalized bone and marrow fibrosis with remodeling of cancellous bone may be observed in condensing osteitis.

In 1990, Jones et al[6] reported three new cases of children with clinical and radiological evidence of condensing osteitis of the clavicle, and concluded that the disorder might be due to low-grade staphylococcal osteomyelitis.

In 1995, Berthelot et al[3] pointed out that the disease tended to occur in bone areas overlaid by fibrocartilage, while not affecting the joint areas covered by hyaline cartilage. They therefore suggested that fibrocartilage might play an important role in the pathogenesis of the disease.

In 1978, Teates et al[12] pointed out the usefulness of a radionuclide bone scan in the diagnostic process; the radionuclide bone scan is characterized by a significant uptake of the tracer at the level of the affected clavicle. All our patients underwent TBS, and we found a strong, localized and isolated hyperfixation of the tracer at the level of the medial half of the affected clavicle in all cases.

During the 1990s MRI proved a useful non-invasive procedure for the diagnosis of condensing osteitis of the clavicle. MRI can reveal edema and sclerosis of the clavicle, most probably indicative of different stages in the disease[13,14]. In all our patients MRI showed morphological alterations of the affected clavicle, and edema of the surrounding soft tissues in all cases.

Although Berthelot et al[3] reported some cases of spontaneous remission, the condition often requires treatment. Kruger et al[7] and Lissens et al[8] report that non-steroidal and anti-inflammatory medications have proved effective in relieving the pain. However, resection of the medial end of the clavicle may be required in refractory cases[4,7,8]. On the other hand, Jones et al[6] observed complete remission of symptoms in the case of antibiotic therapies.

Over the years, a number of different treatment options have been described, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, injection of corticosteroids, and surgical resection of the medial end of the clavicle in refractory cases[4,5,7,8]. However, the best treatment option for this condition is still unknown.

In conclusion, the rarity of this pathology is highlighted by the fact that fewer than 60 proven cases have been reported in the scientific literature (Table 2). Nevertheless, the appearance of a non-traumatic swelling of the clavicle, even in the pediatric age group, should evoke this rare disorder, which should be considered in differential diagnosis (Table 3).

| Disease | Clinical and/or radiological features |

| Osteoarthritis | Narrowed joint space with marginal osteophytes, sclerosis restricted to the sub-chondral bone on both sides of the joint |

| Infection | Bone destruction, synovial abnormality, joint space narrowing, and periosteal reaction |

| Chronic, sclerosing osteomyelitis | Dense sclerosis similar to condensing osteitis of the clavicle, but periosteal reaction and/or foci of bone destruction |

| Osteoblastic lesion | Different age at onset, shorter duration of symptoms, epiphyseal location is atypical, periosteal reaction ± bony destruction, progression on serial studies |

| Metastases | As a solitary bone scan abnormalities in the clavicle epiphysis (unusual) |

| Osteoid osteoma | Classic central lucent nidus |

| Sternoclavicular hyperostosis | Usually bilateral, ossification of sterno-clavicular ligaments, bone scan abnormalities at sternum superior ribs, spinal ligamentous ossification and sacro-iliac abnormalities, systemic and specific dermatologic manifestations (palmoplantar pustulosis) |

| Friedreich’s disease | Shorter duration of symptoms, clearer relationship to trauma, bone scan similar, X-rays similar ± subchondral irregularity and focal lucencies, biopsy: Osteonecrosis is typical (but marrow fibrosis or osteonecrosis have been described in several cases of condensing osteitis of the clavicle) |

| Tietze’s syndrome | Involvement of one or more costal cartilages, the clavicle is not involved on radiographs or scan |

| Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis | The lesion is initially lytic and with healing, sclerotic and expansile, involves the middle two thirds sparing the medial end, and is typically at presentation. Inflammatory process can be seen at histological examination |

| Paget’s disease | Greater area involved, and the bone scan dramatically more abnormal, localizations in other bones, elevated level of alkaline phosphatase occurs in adults |

The potential consequences of a missed diagnosis are that the patient may undergo unnecessary, extensive and costly clinical and radiological investigations, especially if the lesion is thought to be metastatic. Furthermore, although the etiology remains unclear (seemingly either mechanical or an infectious), the complete remission of symptoms reported in our case series as a consequence of the antibiotic treatment suggests an infectious etiology, as in Jones’ hypothesis[6]. Biopsy is, however, necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

We therefore recommend approaching the disease with an appropriate IV and oral antibiotic therapy in order to avoid unnecessary aggressive surgery. Antibiotic treatment should start after the pathology report has confirmed the diagnosis. Resection of the affected medial half of the clavicle should be reserved for refractory cases only.

Condensing osteitis of the clavicle is a rare benign disorder of unknown origin that should be recognized promptly. It is characterized by pain and swelling at the medial end of the clavicle, with increased radio-density. Biopsy is needed to confirm diagnosis. The condition should be treated by parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy.

The potential consequences of a missed diagnosis are that the patient may undergo unnecessary, extensive and costly clinical and radiological investigations, especially if the lesion is thought to be metastatic. Biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

The disease should be approached with an appropriate intra venous (IV) and oral antibiotic therapy in order to avoid unnecessary aggressive surgery. Antibiotic treatment should start after the pathology report has confirmed the diagnosis. Resection of the affected medial half of the clavicle should be reserved for refractory cases only.

The study results suggest that IV and oral antibiotic therapy is effective in controlling the disease.

Condensing osteitis of the clavicle is a rare benign disorder of unknown origin that should be recognized promptly. It is characterized by pain and swelling at the medial end of the clavicle, with increased radio-density.

The manuscript has been described very well. Although it is a case series, the authors summarized the previous literature and presented well.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Tawonsawatruk T, Vulcano E S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Brower AC, Sweet DE, Keats TE. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle: a new entity. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1974;121:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Appell RG, Oppermann HC, Becker W, Kratzat R, Brandeis WE, Willich E. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle in childhood: a rare sclerotic bone lesion. Review of literature and report of seven patients. Pediatr Radiol. 1983;13:301-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Berthelot JM, Mabille A, Nomballais MF, Maugars Y, Robert R, Prost A. Osteitis condensans of the clavicle: does fibrocartilage play a role? A report of two cases with spontaneous clinical and roentgenographic resolution. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1995;62:501-506. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Greenspan A, Gerscovich E, Szabo RM, Matthews JG. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle: a rare but frequently misdiagnosed condition. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hsu CY, Frassica F, McFarland EG. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle: case report and review of the literature. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1998;27:445-447. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Jones MW, Carty H, Taylor JF, Ibrahim SK. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle: does it exist? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:464-467. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kruger GD, Rock MG, Munro TG. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle. A review of the literature and report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:550-557. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lissens M, Bruyninckx F, Rosselle N. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Acta Belg Med Phys. 1990;13:235-240. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Noonan PT, Stanley MD, Sartoris DJ, Resnick D. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle in a man. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27:291-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Outwater E, Oates E. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle: case report and review of the literature. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:1122-1125. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sng KK, Chan BK, Chakrabarti AJ, Bell SN, Low CO. Condensing osteitis of the medial clavicle--an intermediate-term follow-up. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:499-502. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Teates CD, Brower AC, Williamson BR, Keats TE. Bone scans in condensing osteitis of the clavicle. South Med J. 1978;71:736-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vierboom MA, Steinberg JD, Mooyaart EL, van Rijswijk MH. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle: magnetic resonance imaging as an adjunct method for differential diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:539-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rand T, Schweitzer M, Rafii M, Nguyen K, Garcia M, Resnick D. Condensing osteitis of the clavicle: MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:621-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [accessed 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: http: //www.cochrane-handbook.org. |