Published online Jun 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i6.401

Peer-review started: February 3, 2016

First decision: March 21, 2016

Revised: March 23, 2016

Accepted: April 7, 2016

Article in press: April 11, 2016

Published online: June 18, 2016

Processing time: 131 Days and 6.7 Hours

Posterolateral dislocations of the knee are rare injuries. Early recognition and emergent open reduction is crucial. A 48-year-old Caucasian male presented with right knee pain and limb swelling 3 d after sustaining a twisting injury in the bathroom. Examination revealed the pathognomonic anteromedial “pucker” sign. Ankle-brachial indices were greater than 1.0 and symmetrical. Radiographs showed a posterolateral dislocation of the right knee. He underwent emergency open reduction without an attempt at closed reduction. Attempts at closed reduction of posterolateral dislocations of the knee are usually impossible because of incarceration of medial soft tissue in the intercondylar notch and may only to delay surgical management and increase the risk of skin necrosis. Magnetic resonance imaging is not crucial in the preoperative period and can lead to delays of up to 24 h. Instead, open reduction should be performed once vascular compromise is excluded.

Core tip: Posterolateral knee dislocations are uncommon injuries that are often missed or misdiagnosed. We believe that attempts at closed reduction and preoperative magnetic resonance imaging are unnecessary delays to open reduction. We advocate emergent open reduction once vascular integrity is confirmed on ankle-brachial index testing.

- Citation: Woon CY, Hutchinson MR. Posterolateral dislocation of the knee: Recognizing an uncommon entity. World J Orthop 2016; 7(6): 401-405

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i6/401.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i6.401

Posterolateral dislocation of the knee is an uncommon injury. Closed reduction is not possible because of incarceration of medial soft tissue[1,2] and should not be attempted. Open reduction is indicated once this condition is diagnosed and vascular integrity is confirmed. We present a case with posterolateral knee dislocation that presented 3 d after the original injury and discuss the successful management of this injury.

We have obtained the patient’s written informed consent for print and electronic publication of the report. There are no conflicts of interest.

A 48-year-old male slipped and fell in the bathroom, striking his knee on the bathtub and sustaining a twisting injury to his right knee. He was only able to bear minimal weight on the extremity, and lay on his bed for 3 d prior to presentation. His roommates finally called for an ambulance because of unrelenting pain and increasing swelling of the entire lower extremity. His history was otherwise unremarkable except for smoking (a few cigarettes a day) and alcohol use (1 can of beer every few days).

On presentation in the emergency room, the limb was grossly swollen from the mid-thigh to the ankle, with blistering over the distal anteromedial thigh. The knee was held in slight flexion. There was ecchymotic discoloration and transverse “puckering” over the distal anteromedial thigh, and a smooth, bony prominence was palpable subcutaneously proximal to the “pucker” (Figure 1). There was diffuse tenderness around the knee. Leg swelling was soft and not suggestive of compartment syndrome. Dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were strong and the foot was warm and pink. The ankle-brachial index (ABI) exceeded 1.0 for both lower extremities. Toe plantar- and dorsiflexion strength was Medical Research Council Grade 5 and sensation was preserved. Radiographs revealed a posterolateral dislocation of the knee (Figure 2). He was taken to the operating room emergently that evening.

Under general anesthesia, the knee was inspected and brought through its range of motion (Figure 3). Under tourniquet control, and incision was made over the anteromedial leg and thigh, directly over the “pucker”. There was a large rent in the medial soft tissue, and the medial femoral condyle was found lying in the subcutaneous plane. The medial patellar retinaculum, capsule, medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), vastus medialis, meniscotibal and meniscofemoral ligaments were found incarcerated within the intercondylar notch of the femur. These tissues were freed and reduced back to their original subcutaneous position, allowing the femur to be easily translated and reduced laterally over the tibial plateau. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) was torn at its femoral attachment, and the anterior cruciate ligament were ruptured but the posterior cruciate ligament was intact. The MPFL and vastus medialis rent was reapproximated with Ethibond 5. The medial retinaculum was imbricated over the repair with Vicryl 1 to reinforce the repair. The incision was then closed in layers in the usual fashion. Postoperative pulses were strong on the operated limb and postoperative ABI was 1.34 and 1.28 for the posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses on the operated side, respectively, and 1.3 and 1.25 for the contralateral, non-operated side, respectively.

His knee pain resolved completely after surgery and compartments remained soft. He was allowed to bear weight as tolerated in a hinged knee brace locked in extension for 6 wk postoperatively. At 6-wk follow-up, he was ambulating independently in the knee brace and the surgical incision had healed completely.

Posterolateral dislocations of the knee are uncommon entities. They can arise from very low energy trauma comprising a valgus moment to a slightly flexed knee, with the tibia rotating relative to the femur. The exact direction of rotation of the tibia relative to the femur is subject to debate[1,3]. An axial load is then necessary to allow the medial femoral condyle to buttonhole through the adjacent soft tissue[1]. The key to managing these injuries is to recognize that closed reduction may not be possible, and the patient should be brought to the operating room as soon as is reasonably possible for an open reduction.

The pathognomonic sign of a posterolateral knee dislocation is the anteromedial distal thigh transverse “pucker” or “dimple sign”. While this is immediately obvious with the knee in extension, the anteromedial “pucker” is accentuated by flexion. This is because the medial retinaculum, vastus medialis and MPFL tissue normally translate proximally with knee flexion. With the tissue trapped in the intercondylar notch, proximal translation is not possible and soft tissue attachments invaginate the skin inwards towards the intercondylar notch during flexion, making the “pucker” more prominent (Figure 3). To avoid discomfort, we recommend that knee flexion only be attempted under anesthesia. Another pathognomonic sign is the presence of the medial femoral condyle in the immediate subcutaneous location as a smooth, bony prominence proximal to the “pucker”, almost “tenting” the skin. This is because all adjacent soft tissue (capsule, MPFL, vastus medialis, medial retinaculum) has receded around the condyle, allowing it to buttonhole through the tissue and come into prominence. Again, this is accentuated by knee flexion. Similar to other types of knee dislocation, determining the range of motion of an unreduced knee at presentation is unnecessary.

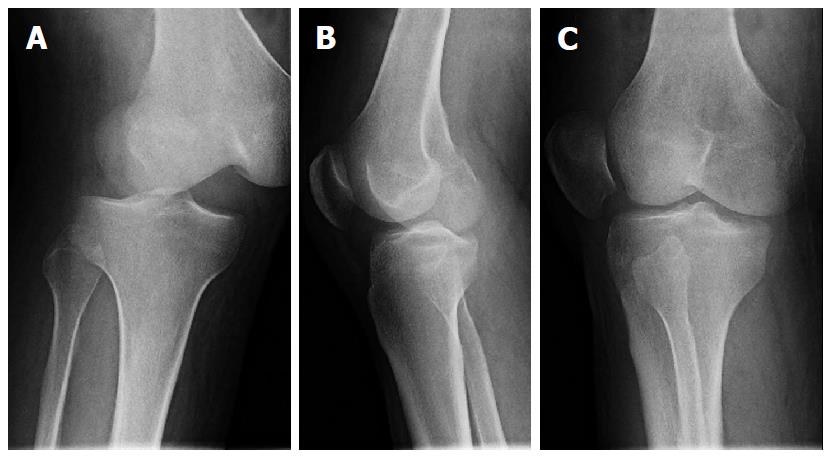

Radiographs are also pathognomonic of a posterolateral knee dislocation. Much like rotatory dislocations of the proximal phalangeal joint of the finger, radiographs of a posterolateral knee dislocation will not reveal a true anteroposterior (AP) or lateral view of both the tibia and the femur in any single radiograph. An additional telltale sign is the view of the patella. This is because the patella maintains its in-line attachments to the tibial tuberosity (patellar tendon and quadriceps tendon) and will appear reduced with respect to the proximal tibia, but dislocated with respect to the distal femur. Thus, an AP radiograph of the knee will likely demonstrate an AP of the proximal tibia and an oblique of the distal femur (Figure 2A). Because the AP radiograph is shot directly over the patella with the patella facing the ceiling, the patella will appear in an AP projection also. In addition, medial opening of the tibiofemoral joint is noted, suggestive of medial soft tissue interposition[1]. Similarly, a lateral radiograph of the knee will show a lateral of the proximal tibia and patella, but an oblique of the femur (Figure 2B). An effusion is usually appreciated on the lateral projection as well[4], however in our patient, this was replaced by diffuse soft tissue swelling of the entire limb because of the interval to presentation. An oblique projection will appear to show apparent patella dislocation relative to the femur (Figure 2C).

Similar to other types of knee dislocations, ensuring distal limb viability and preservation of vascularity is of utmost importance. Evaluation of preoperative ABI will allow stratification for further vascular evaluation, and possible skeletal immobilization and vascular exploration, if necessary. It also provides a valuable baseline reading for comparison postoperatively. In a prospective study of 38 knee dislocations, Mills et al[5] found that ABIs < 0.9 had sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value of 100% and ABI > 0.9 had negative predictive value of 100% for arterial injury necessitating surgical intervention. While some authors perform computed tomography angiograms routinely for posterolateral knee dislocation (Table 1)[2,4], we believe that in the presence of palpable pulses, a warm foot and normal ABIs, further vascular imaging is but an unnecessary delay. In a review of reports of posterolateral knee dislocations, only 1 author reported loss of pulses (Table 1). This was because of a high-energy dislocation.

| Ref. | Patient age and gender | Torn structures (besides medial capsule, retinaculum, vastus medialis, MPFL) | MRI | Doppler | Angiogram/CT angiogram | Attempted closed reduction | Arthroscopic surgery | Interval to open reduction | Open surgery |

| Current study | 48 M | MCL, ACL | No | Yes | No | No | No | 4 h | Yes |

| Nystrom et al[8] | 24 M and 31 F | MCL, ACL, PCL | No | No | No | Yes | No | Not mentioned | Yes |

| Huang et al[1] | 61 M | ACL, PCL, MCL (also degenerative arthrosis) | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | > 8 h | Yes |

| Jeevannavar et al[2] | 32 M | MCL, medial retinaculum, partial ACL tear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not mentioned | Yes |

| Paulin et al[4] | 54 M | ACL, PCL, MCL, LCL | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | < 24 h | Yes |

| Quinlan et al[3] | 38 M, 40 F, 49 M, 20 M, 41 F | ACL, PCL, MCL in all patients, additional medial meniscus tear in 1 patient | No | No | No | 3 of 5 cases | No | 24 h in 4 cases, few days later in 1 case | Yes |

| Ashkan et al[7] | 37 M | ACL, PCL, MCL, LCL, PLC | No | No | No | Yes | No | Following thoracoabdominal surgery | Yes |

| Urgüden et al[9] | 51 M and 53 F | Medial retinaculum, MCL, ACL, PCL | No | Yes in 1 patient | No | Yes | No | 4 h in both | Yes |

Some authors advocate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Table 1)[2,4] to demonstrate torn structures interposed in the intercondylar notch, evaluate the integrity of the cruciate and collateral ligaments, and demonstrate the pathognomonic MR “dimple sign”[6]. We feel that these findings are equally easily discerned following the skin incision. An urgent MRI does not alter surgical management acutely, and urgent surgical reduction should take priority. Further, the distorted anatomy of an unreduced knee may also impair the diagnostic accuracy of MRI. While cruciate ligament ruptures may be picked up on MRI, these need not be addressed in the emergent setting[2]. Should the patient present with late symptoms or persistent instability in the postoperative period after a period of soft tissue healing, the cruciate ligaments can be easily evaluated with an MRI at that time.

Unlike other permutations of knee dislocation, closed reduction of posterolateral knee dislocation is rarely possible. While some authors advocate attempting a closed reduction (Table 1)[1,7-9], we feel that these attempts are both uncomfortable and unnecessary and serve only to increase the prominence of soft tissue puckering and jeopardize the viability of the already tenuous soft tissue envelope[1], and delay surgical management. Similar to other dislocations involving buttonholing of bony prominences through soft tissue, the classic reduction maneuver of in-line traction functions only to tighten torn tissue around the condylar expansion.

Some authors attempt arthroscopic- or arthroscopic-assisted reduction prior to open reduction, both in an attempt to spare the patient a disfiguring incision, and to allow for closer intra-articular inspection[1]. There are some limitations to this approach. Normal bony anatomy is distorted, making localization of the usual arthroscopic portals difficult. Because of capsular rupture, containment of insufflation fluid is not possible, leading to progressive extravasation, aggravating existing soft tissue edema and swelling, potentially increasing intracompartmental pressures. Entrapped tissue in the intercondylar notch is often on tension, and cannot be extricated by an arthroscopic probe alone[1]. Further, it is not possible to reapproximate torn medial structures arthroscopically, and a final extensile medial incision is inevitable.

Surgical reduction should be performed emergently to reduce the risk of skin necrosis at the point of maximal invagination and tethering[1,2]. The surgical technique for open reduction is not difficult. The surgical approach is extensile and direct, and targeted at achieving maximal exposure of torn structures and the buttonholed medial femoral condyle. Following division or reduction of the interposed tissue, reduction is achieved almost instantaneously by translating the femur laterally with minimal effort. These soft tissues can include medial capsule, retinaculum, MCL, MPFL, vastus medialis and medial meniscus. Division of interposed tissue may be necessary if there is tight contracture, especially in late-presenting cases.

Postoperatively, the knee is protected in a hinged knee brace during mobilization. Besides torn medial structures and cruciate ligaments, some authors have found avulsion of lateral structures including the lateral collateral ligament from its femoral attachment[4]. Protected weight-bearing will allow for healing of torn, repaired and reapproximated structures. Long term follow-up is necessary to detect the onset of post-traumatic arthritis.

Posterolateral dislocations of the knee are uncommon entities. Early recognition is key. Pathognomonic findings include the anteromedial “pucker” sign that is accentuated by knee flexion, and characteristic radiographs that do not show the same projections of the long bones in any single view. Attempting closed reduction will not be a rewarding endeavor. Instead, open reduction should be performed as soon as vascular compromise is excluded. MRI is not crucial in the preoperative period and can lead to delays of up to 24 h and can compromise the overlying soft tissue envelope[4]. MRI can be obtained postoperatively following a period of soft tissue healing in patients with persistent symptoms.

A 48-year-old man presented with right knee pain and swelling 3 d after twisting his right knee during a fall.

Gross swelling of the right thigh to ankle with distal thigh blistering. “Pucker” sign was visible over the distal anteromedial thigh. Subcutaneous bony prominence (medial femoral condyle) was palpable proximal to the pucker. Pulses were strong and ankle-brachial index was > 1.0 bilaterally.

Knee septic arthritis, knee effusion, deep vein thrombosis, compartment syndrome, anterior knee dislocation, posterior knee dislocation, cruciate or collateral ligament injury, tumor.

All labs within normal limits.

Radiographs revealed posterolateral dislocation of the knee.

Posterolateral dislocation of the knee.

Operative open reduction and repair of medial retinaculum, medial patellofemoral ligament and vastus medialis.

Posterolateral knee dislocations are uncommon and can be missed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will only delay treatment. Closed reduction may not be possible. Urgent open reduction is necessary to preserve the tenuous soft tissue envelope.

This condition is uncommon. Urgent open reduction is often necessary as closed reduction is usually impossible. MRI in the acute setting will only serve to delay open reduction and will not guide immediate management.

The authors reported a rare case of posterolateral dislocations of the knee. It is a well written case report.

P- Reviewer: Knutsen G, Martinelli N, Zheng N S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Huang FS, Simonian PT, Chansky HA. Irreducible posterolateral dislocation of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jeevannavar SS, Shettar CM. ‘Pucker sign’ an indicator of irreducible knee dislocation. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii: bcr2013201279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Quinlan AG, Sharrard WJ. Postero-lateral dislocation of the knee with capsular interposition. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1958;40-B:660-663. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Paulin E, Boudabbous S, Nicodème JD, Arditi D, Becker C. Radiological assessment of irreducible posterolateral knee subluxation after dislocation due to interposition of the vastus medialis: a case report. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:883-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Mills WJ, Barei DP, McNair P. The value of the ankle-brachial index for diagnosing arterial injury after knee dislocation: a prospective study. J Trauma. 2004;56:1261-1265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Harb A, Lincoln D, Michaelson J. The MR dimple sign in irreducible posterolateral knee dislocations. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:1111-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ashkan K, Shelly RW, Barlow IW. An unusual case of irreducible knee dislocation. Injury. 1998;29:383-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nystrom M, Samimi S, Ha’Eri GB. Two cases of irreducible knee dislocation occurring simultaneously in two patients and a review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;277:197-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Urgüden M, Bilbaşar H, Ozenci AM, Akyildiz FF, Gür S. Irreducible posterolateral knee dislocation resulting from a low-energy trauma. Arthroscopy. 2004;20 Suppl 2:50-53. [PubMed] |