Published online Mar 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i3.188

Peer-review started: February 4, 2015

First decision: July 6, 2015

Revised: December 3, 2015

Accepted: December 18, 2015

Article in press: December 20, 2015

Published online: March 18, 2016

Processing time: 399 Days and 19.3 Hours

AIM: To demonstrate that long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) tenodesis is possible more than 3 mo after rupture.

METHODS: From September 2009 to January 2012 we performed tenodesis of the LHBT in 11 individuals (average age 56.9 years, range 42 to 73) more than 3 mo after rupture. All patients were evaluated by Disabilites of the Arm Shoulder and Hand (DASH) and Mayo outcome scores at an average follow-up of 19.1 mo. We similarly evaluated 5 patients (average age 58.2 years, range 45 to 64) over the same time treated within 3 mo of rupture with an average follow-up of 22.5 mo.

RESULTS: Tenodesis with an interference screw was possible in all patients more than 3 mo after rupture and 90% had good to excellent outcomes but two had recurrent rupture. All of those who had tenodesis less than 3 mo after rupture had good to excellent outcomes and none had recurrent rupture. No statistical difference was found for DASH and Mayo outcome scores between the two groups (P <0.05).

CONCLUSION: Tenodesis of LHBT more than 3 mo following rupture had outcomes similar to tenodesis done within 3 mo of rupture but recurrent rupture occurred in 20%.

Core tip: While some think long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) tenodesis is not possible more than 3 mo after rupture, we have demonstrated that it is and will yeld to outcomes similar to tenodesis done within 3 mo. The LHBT tenodesis was achieved in all patients affected by chronic rupture.

- Citation: McMahon PJ, Speziali A. Outcomes of tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon more than three months after rupture. World J Orthop 2016; 7(3): 188-194

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i3/188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i3.188

Rupture of the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) is common, accounting for 96% of all biceps brachii injuries[1] and is generally treated non-operatively. The LHBT is a flexor of the elbow and a supinator of the forearm and also it flexes and medially rotates the shoulder[2].

Studies that focused on results following chronic LHBT rupture[3-5] have found disabilities could include persistent muscle pain, biceps spasm, strength loss and popeye deformity. The loss of strength has been reported at the elbow, not the shoulder, and is not insignificant. Soto-Hall and Stroot[6] reported a 20% loss of elbow flexion strength, Deutch et al[3] demonstrated a 23% loss of supination strength and a 28% loss of flexion strength at the elbow and Sturzenegger et al[5] found a strength deficiency of 16% in flexion and 12% in supination. The popeye deformity is a cosmetic abnormality resulting from distal displacement of the long head of the biceps muscle that in part, gives the appearance of the biceps muscle being bigger.

Despite the popeye deformity and loss of elbow strength, few patients have persistent pain and muscle spasm after LHBT rupture so most are satisfied with non-operative treatments. In the past, surgery has been almost exclusively reserved for active patients with acute rupture within 3 mo of rupture and persistent symptoms[7-9].

Acute tenodesis of LHBT rupture has yielded good to excellent results in most patients. Mariani et al[10] performed a tenodesis to the proximal humeral shaft within 12 wk of rupture and, after 13 years, only 7.4% of patients reported mild to moderate bicipital pain, 37% reported mild to moderate deformity at the biceps, 14.8% subjective weakness at the elbow and only 11.1% poor clinical outcome and arm disability. Gumina et al[11] performed a tenodesis of the LHBT to the coracoid process less than 10 d after rupture and good to excellent clinical outcomes in 78.6% of patients. Tangari et al[12] performed a tenodesis into the bicipital groove after an average of 3 d following rupture. By 5 mo, none reported abnormal cosmetic appearance of the biceps and all of them returned to their professional activity.

But some patients first seek treatment more than 3 mo after rupture and in some the diagnosis is missed. Also, it is often difficult to predict those that will have persistent symptoms with non-operative treatment and lastly, tenolysis of the LHBT can result in pain and biceps spasm that persist more than 3 mo after rupture.

Tenodesis more than 3 mo after LHBT rupture has been thought to be complicated by scarring and retraction of the biceps tendon that precludes success[13,14]. So, most surgeons do not offer surgery for individuals more than 3 mo after rupture. A case report of LHBT tenodesis 18 mo after rupture found return to full activity and no popeye deformity 6 mo later[15]. In a prior series of 11 symptomatic patients who were treated at least 3 mo after rupture while the LHBT was too short for the authors’ preferred method of tenodesis in 6, 3 reported normal cosmetic appearance and patient subjective self-assessments of strength and pain were satisfactory in over 70%[14].

The purpose of this study is to report the surgical technique and objective clinical outcomes in a series of patients with LHBT tenodesis done more than 3 mo after rupture. First, we hypothesize that LHBT tenodesis done more than 3 mo after LHBT rupture can be done reliably with an interference screw technique. Second, we hypothesize that the outcomes will be similar to those within 3 mo of rupture.

From September 2009 to January 2012 tenodesis of LHBT rupture was performed in 16 patients by a single surgeon (PJM). Exclusion criteria were: (1) previous surgery on the affected shoulder; (2) osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint; and (3) age > 75 years. All patients complained of biceps pain, weakness and persistent spasm of the biceps muscle with resisted elbow flexion activities (Tables 1 and 2) and were informed and gave their consent to the procedure and participation in the study. While there was a “popeye” deformity of the biceps muscle following a traumatic event, such as heavy lifting, or a fall, or while playing hockey, none had surgery for cosmetic reasons alone. The patients were divided into two groups, chronic which was more than 3 mo after rupture and acute which was less than or equal to 3 mo. In the chronic group 11 patients, one female and ten males, underwent LHBT tenodesis more than 3 mo after rupture and the mean time from rupture to surgery was 30.1 (range: 3.5 to 240) mo (Table 3). Two patients reported they had LHBT rupture and associated disabilities for 20 years and “several years”, respectively. All the patients in this group had failed to improve after a rehabilitation program. In the acute group were included 5 patients, all males, who underwent tenodesis 1.7 (1 to 2) mo after LHBT rupture (Table 4). All patients had a shoulder arthroscopy prior to the open biceps surgery.

| Patient | Age (yr), sex, injured side | Rupture-to-surgery (mo) | Mechanism of rupture | Occupation |

| 1 | 59, M, R1 | 4 | Lifting | Minister |

| 2 | 73, M, L1 | 6 | Fall | Retired |

| 3 | 68, M, L1 | Several years | Unknown | Retired |

| 4 | 56, F, L1 | 4 | Lifting | Mental therapist |

| 5 | 48, M, R1 | 6 | Fall | Police officer |

| 6 | 58, M, R1 | 8 | Playing hokey | Teacher |

| 7 | 42, M, R1 | 3.5 | Lifting | Electrician |

| 8 | 51, M, R1 | 240 | Water skiing | Massage therapist |

| 9 | 61, M, R1 | 12 | Lifting | Retired |

| 10 | 57, M, L1 | 13 | Heavy lifting | Manager |

| 11 | 53, M, R2 | 5 | Lifting | Carpenter |

The mean age at the time of the surgery was 56.9 (42 to 73) years in the chronic group and 58.2 (45 to 64) years in the acute group. Occupation was varied and included manual laborers, managers and retired individuals. In the chronic group, ten patients were right-handed and seven ruptured the right side. In the acute group, all patients were right-handed and three ruptured the right side.

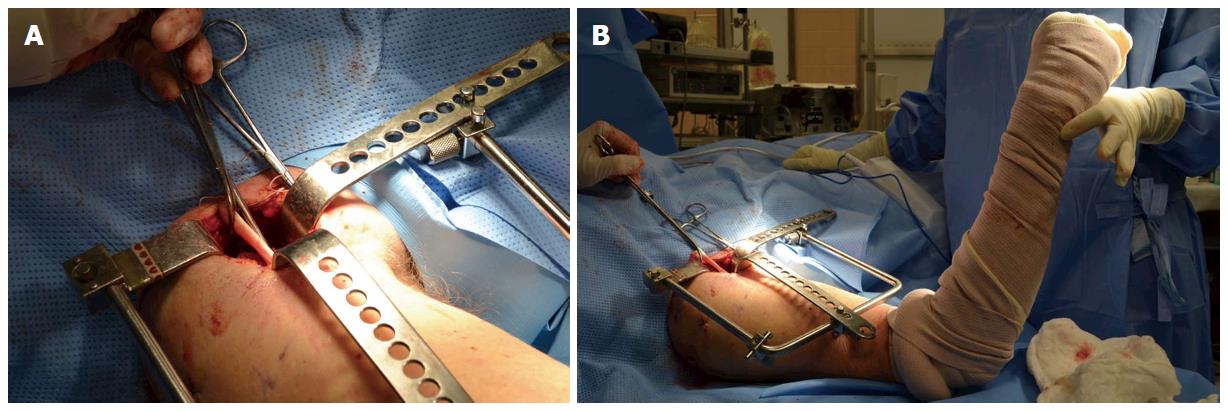

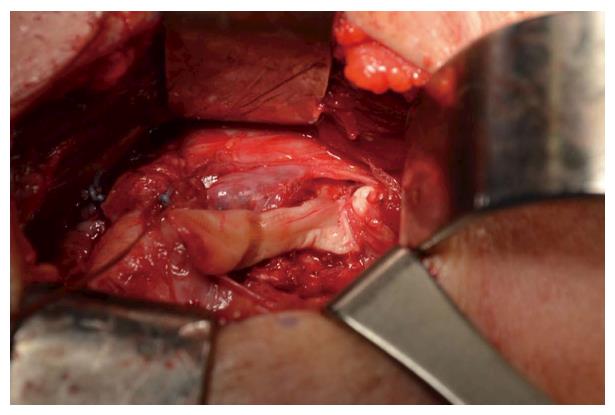

Each patient had a deltopectoral incision about 6 cm in length and the superior 1 cm of the pectoralis tendon insertion onto the humerus is incised and the posterior pectoralis tendon was probed with a finger. This was where the proximal LHBT had often retracted and scarred and if it could be palpated, it is then hooked with the finger and brought into the wound and freed from the pectoralis tendon using sharp dissection. More often, the LHBT was difficult to palpate at the posterior pectoralis tendon and then a separate 4 cm incision was made at the superior aspect of the popeye muscle. After dissection through the subcutaneous tissue the myotendinous junction of the long head of the biceps muscle was palpated and the LHBT was palpated and freed with fingers in both incisions, most often from its scarred location posterior to the pectoralis. It was then brought out of the distal wound (Figure 1A) and the end of the tendon was resected with a scalpel. This separate incision at the superior aspect of the popeye muscle was used as prior attempts to find the LHBT with a deltopectoral incision alone often resulted in the LHBT being difficult to find or too short for interference screw fixation. In pilot study, indentifying the tendon distally and then using both incisions to dissect the scarred tendon from the posterior pectoralis tendon resulted in a robust and long tendon. Tenodesis was done with more tension in those greater than 3 mo after rupture than in those less than 3 mo; we tensioned the tenodesis with the elbow flexed 60 degrees (Figure 1B). We performed a suprapectoralis tenodesis with fixation at the bottom of the bicipital groove by re-routing the tendon from the distal incision to the proximal incision under the pectoralis tendon. Fixation in all patients was with a bioabsorbable interference screw (Figure 2, DePuy, Mitek, Inc, MA, USA). The normal appearance of the biceps muscle was restored.

After the procedure, the patient’s arm is placed in a sling. A few days after surgery, the patient began pendulum exercises and elbow stiffness resolved within 2 wk of surgery. Active ROM was begun at 4 wk and strengthening was begun at 3 mo after the surgery.

The self-assessment of symptoms and function of the upper extremity were evaluated with the Disabilites of the Arm Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire which evaluates the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand with a score from 0 (no symptoms, full function) to 100 (most severe disability)[16]. For assessment of elbow function, the Mayo elbow performance score was administered which includes 45 points for pain, 20 for motion, 10 for stability and 25 for daily activities[17]. An overall score more than 90 means excellent, from 89 to 75 is good, from 75 to 60 is fair and less than 60 is poor.

Statistical analysis was performed with the Mann-Whitney test to compare the DASH and Mayo scores between the two groups and with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare the pre- and post-operative scores within the same group, significance was set at P < 0.05 (IBM-SPSS statistics). Lastly, a power analysis was performed with G*Power 3.1.5 version (α = 0.05, β = 0.80).

No infection, stiffness or other complications were found following LHBT tenodesis in any of the patients. At an average follow-up of 19.1 (range: 9 to 35) mo, 10 patients were available in the chronic group: 9 (90%) patients reported full recovery to daily work and sports activities, no biceps pain, no spasm and the strength was comparable with the opposite side (Table 5).

| Patient | Strength | ||||||||

| Pre-op | Post-op | Contralateral | |||||||

| AB | ER | IR | AB | ER | IR | AB | ER | IR | |

| 1 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 2 | 2/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 3 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 4 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 6 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 7 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 8 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 9 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 10 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 11 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

Two patients had a popeye deformity of the biceps (20%) but only one of them (10%) had a poor outcome with recurrent muscular spasm, mild to moderate persistent pain and weakness at the biceps.

At an average follow-up of 22.5 (12 to 31.5) mo, 5 patients were available in the acute group: All the patients reported full recovery to daily work and sports activities, no biceps pain, no spasm, strength was comparable to the opposite side (Table 6) and there were no popeye deformities.

| Patient | Strength | ||||||||

| Pre-op | Post-op | Contralateral | |||||||

| AB | ER | IR | AB | ER | IR | AB | ER | IR | |

| 1 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 2 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 3 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 4 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

In the chronic group the average pre-operative DASH score was 37.2 (range 29.2 to 55, P = 0.859) and at follow-up there was a significant improvement to 11.2 (range 0 to 35, P = 0.679) with a score change of 26 (range 20 to 29.2, P = 0.001). In the acute group the average pre-operative DASH score was 35.9 (range 30 to 45.8, P = 0.859) and the post-operative score was 7.3 (range 2.5 to 10.83, P = 0.679) showing a significant decrease of 28.6 (range 25.4 to 38.3, P = 0.001) points. We found no statistical significant difference between the two groups with the DASH score (P = 0.679).

In the chronic group the pre-operative Mayo performance was 57.5 (range 45 to 70, P = 1.0) and at follow-up the average score significantly increased (P = 0.001) to 86 (range 85 to 100, P = 0.859). In the acute group the pre-operative Mayo performance score was poor in most the patients (mean score 57, range 50 to 65, P = 1.0), and there was a significant improvement (P = 0.001) to excellent or good in all the patients following surgery (mean score 91, range 85 to 100, P = 0.859). Statistical analysis showed no significant difference between the chronic and acute group in assessment with the Mayo performance score (P = 0.859).

LHBT tenodesis is possible more than 3 mo after rupture, and outcomes were similar to that after acute tenodesis. In the chronic group, we found a 90% excellent to good clinical outcomes and a 20% rate of popeye deformity. Only 1 of the 2 patients with popeye deformity reported a poor outcome. This is comparable to results reported prior following acute LHBT tenodesis[14]. Mariani et al[10] reported a mild to moderate biceps deformity in 37% of patients and a complete recovery of daily activities in 89% of patients. De Carli et al[18] reported excellent to good clinical outcome in 94.2% of patients. Checchia et al[19] reported a 93.4% rate of satisfactory results. Hsu et al[20] reported a 25% incidence of recurrent rupture; Boileau et al[7] reported a 3% incidence of recurrent rupture, 9% incidence of muscular cramping, and 30% rate of pain at the bicipital groove. Koh et al[21] reported 83.7% of excellent to good clinical outcomes, 4.6% incidence of cramping pain, and a 9.3% rate of recurrent rupture. Lastly, in a systematic review Slenker et al[22] found excellent to good clinical outcomes in 74% of patients, an 8% incidence of recurrent rupture, and a 24% rate of bicipital pain.

While chronic rupture of the LHBT is usually asymptomatic, successful biceps tenodesis is important for some active patients who suffer with long-term cramping, pain and weakness. It also is helpful in the treatment of patients with persistent symptoms who first seek treatment more than 3 mo after LHBT rupture and in others in whom the diagnosis was missed. It also eases the difficulty surgeons have in making the decision for surgery within 3 mo as contrary to the beliefs of most surgeons, if symptoms persist in the long-term, biceps tenodesis can still be successful. Lastly, when tenolysis of the LHBT results in pain and biceps spasm that persist for more than 3 mo, LHBT tenodesis is still possible.

Many proximal biceps tenodesis techniques, both arthroscopic[13,23-26] and open[12,27-29] have been described. We used interference screw fixation as prior biomechanical study had found it to have cyclic displacement and load at failure that are better than other fixation techniques immediately after surgery[28]. No infection, stiffness or other complications were found consistent with prior studies that found low incidence of complications after open LHBT tenodesis, specifically a 0.28% incidence of infection and a 0.28% incidence of neuropathies[30]. After more than 3 mo from LHBT rupture, an arthroscopic tenodesis is not currently suitable for two reasons. First, the LHBT is usually retracted to the pectoralis tendon or distal to it. Second, the LHBT is sometimes short, warranting tenodesis more distal than usual.

There are few reports of tenodesis of chronic LHB ruptures. Tucker[31] described their technique of chronic LHBT tenodesis in three patients but no results were reported. Ng and Funk[14] reported their patient’s subjective self-assessments of strength and pain and improvements of 74% and 79% respectively but only 3 of 11 patients had a normal cosmetic appearance. We achieved a normal cosmetic appearance in many more of our patients, 80% in all. This may have been partly from our retrieval of the LHBT with a separate 4 cm incision at the superior aspect of the “popeye” muscle when it could not be found with a deltopectoral incision, partly from our tensioning of the biceps tenodesis at 60° of elbow flexion and partly from our being able to reliably tenodesis the LHBT with an interference screw. Different from prior studies, we also performed objective scores and our improvements in these scores surpassed those prior demonstrated to be clinically relevant[32,33].

Our study has several limitations. More patients with chronic rupture were included in the study because the senior author was known in his community that he was willing to operate on them. Still, the number of patients is small and while an interference screw could reliably be used for the tenodesis, surgeons should counsel patients and be prepared for other techniques in accordance with prior study[14] despite the surgical improvements we report. In addition, associated morbidities could have influenced the outcome scores however the Popeye deformity was restored in 80%. While there were no statistical differences between the outcome scores after chronic and acute tenodesis, there were 2 recurrent ruptures in the chronic group and none in the acute group. A post hoc power analysis revealed that over a thousand of patients would be required to detect a statistical difference (α = 0.05, β = 0.8) between outcome scores between the two groups.

The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) is a flexor of the elbow and a supinator of the forearm. Rupture of the LHBT is common, and is generally treated non-operatively. However disabilities could persist after LHBT rupture such as muscle pain, biceps spasm, strength loss and popeye deformity.

Tenodesis more than 3 mo after LHBT rupture has been thought to be complicated by scarring and retraction of the biceps tendon that precludes success. So, most surgeons do not offer surgery for individuals more than 3 mo after rupture.

Contrary to what many surgeons think, tenodesis with an interference screw more than 3 mo after LHBT rupture is possible and this confirmed the authors’ hypothesis. Outcome is similar to that after tenodesis within 3 mo of rupture but there were 2 recurrent ruptures in those treated more than 3 mo after rupture. Those results are comparable to acute LHBT tenodesis recently performed by other authors (De Carli et al, 2012; Koh et al, 2010; Gumina et al, 2011; Ng and Funk, 2012).

Tenodesis after LHBT rupture should be considered for patients with persistent complaints of pain, weakness and biceps muscle spasm and should not be limited to those within 3 mo of rupture. It also is helpful in the treatment of patients with persistent symptoms who first seek treatment more than 3 mo after LHBT rupture and in others in whom the diagnosis was missed. It also eases the difficulty surgeons have in making the decision for surgery within 3 mo as contrary to the beliefs of most surgeons, if symptoms persist in the long-term, biceps tenodesis can still be successful.

Bicep tenodesis: This procedure involves the reattachment of the LHBT to the humeral bone. A guide wire and reamer is used to make a bone tunnel in the humerus; Interference screw: The fixation of the LHBT into the humeral bone tunnel is performed using a resorbable threated screw; Muscular spasm: Is a sudden involuntary contraction of a muscle, or a group of muscles, accompanied by pain, but is usually harmless and ceases after few minutes.

The authors investigated the outcomes of tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon more than 3 mo after rupture compared with those performed within 3 mo, and found that the outcomes are similar after 3 mo rupture to those within 3 mo rupture.

P- Reviewer: Gao BL S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Carter AN, Erickson SM. Proximal biceps tendon rupture: primarily an injury of middle age. Phys Sportsmed. 1999;27:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Glousman R, Jobe F, Tibone J, Moynes D, Antonelli D, Perry J. Dynamic electromyographic analysis of the throwing shoulder with glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:220-226. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Deutch SR, Gelineck J, Johannsen HV, Sneppen O. Permanent disabilities in the displaced muscle from rupture of the long head tendon of the biceps. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2005;15:159-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Klonz A, Reilmann H. [Biceps tendon: diagnosis, therapy and results after proximal and distal rupture]. Orthopade. 2000;29:209-215. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sturzenegger M, Béguin D, Grünig B, Jakob RP. Muscular strength after rupture of the long head of the biceps. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1986;105:18-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soto-Hall R, Stroot JH. Treatment of ruptures of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Orthop. 1960;2:192-193. |

| 7. | Boileau P, Baqué F, Valerio L, Ahrens P, Chuinard C, Trojani C. Isolated arthroscopic biceps tenotomy or tenodesis improves symptoms in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:747-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elser F, Braun S, Dewing CB, Giphart JE, Millett PJ. Anatomy, function, injuries, and treatment of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:581-592. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Walch G, Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Nové-Josserand L, Neyton L, Szabo I. Arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of the biceps in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: clinical and radiographic results of 307 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:238-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 429] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mariani EM, Cofield RH, Askew LJ, Li GP, Chao EY. Rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;233-239. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Gumina S, Carbone S, Perugia D, Perugia L, Postacchini F. Rupture of the long head biceps tendon treated with tenodesis to the coracoid process. Results at more than 30 years. Int Orthop. 2011;35:713-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tangari M, Carbone S, Gallo M, Campi A. Long head of the biceps tendon rupture in professional wrestlers: treatment with a mini-open tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:409-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Richards DP, Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic-assisted biceps tenodesis for ruptures of the long head of biceps brachii: The cobra procedure. Arthroscopy. 2004;20 Suppl 2:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ng CY, Funk L. Symptomatic chronic long head of biceps rupture: Surgical results. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2012;6:108-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cope MR, Ali A, Bayliss NC. Biceps rupture in body builders: three case reports of rupture of the long head of the biceps at the tendon-labrum junction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:580-582. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Angst F, Schwyzer HK, Aeschlimann A, Simmen BR, Goldhahn J. Measures of adult shoulder function: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) and its short version (QuickDASH), Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Society standardized shoulder assessment form, Constant (Murley) Score (CS), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS), Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ), and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11:S174-S188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Morrey BF. Functional evaluation of the elbow. Morrey BF, editor. The elbow and its disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 2000; 82. |

| 18. | De Carli A, Vadalà A, Zanzotto E, Zampar G, Vetrano M, Iorio R, Ferretti A. Reparable rotator cuff tears with concomitant long-head biceps lesions: tenotomy or tenotomy/tenodesis? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:2553-2558. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Checchia SL, Doneux PS, Miyazaki AN, Silva LA, Fregoneze M, Ossada A, Tsutida CY, Masiole C. Biceps tenodesis associated with arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:138-144. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hsu AR, Ghodadra NS, Provencher MT, Lewis PB, Bach BR. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a review of clinical outcomes and biomechanical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:326-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Koh KH, Ahn JH, Kim SM, Yoo JC. Treatment of biceps tendon lesions in the setting of rotator cuff tears: prospective cohort study of tenotomy versus tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1584-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Slenker NR, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Dodson CC, Cohen SB. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:576-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ahmad CS, ElAttrache NS. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:499-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Coste JS, Walch G. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis: a new technique using bioabsorbable interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:1002-1012. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Gartsman GM, Hammerman SM. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis: operative technique. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:550-552. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Romeo AA, Mazzocca AD, Tauro JC. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:206-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Froimson AI, O I. Keyhole tenodesis of biceps origin at the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;245-249. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Mazzocca AD, Rios CG, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wiley WB, Meyers JF, Weber SC, Pearson SE. Arthroscopic assisted mini-open biceps tenodesis: surgical technique. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:444-446. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Nho SJ, Reiff SN, Verma NN, Slabaugh MA, Mazzocca AD, Romeo AA. Complications associated with subpectoral biceps tenodesis: low rates of incidence following surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:764-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tucker CJDA. Tenodesis of isolated proximal ruptures of the long head of the biceps brachii. Tech Shoulder Surg. 2009;10:72-75. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Wright JG, Tarasuk V, Bombardier C. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;14:128-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 945] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Roy JS, MacDermid JC, Woodhouse LJ. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of four questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:623-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |