Published online Oct 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.678

Peer-review started: March 1, 2016

First decision: March 21, 2016

Revised: July 29, 2016

Accepted: August 17, 2016

Article in press: August 18, 2016

Published online: October 18, 2016

Processing time: 225 Days and 8.7 Hours

To compare mortality and time-to-surgery of patients admitted with hip fracture to our teaching hospital on weekdays vs weekends.

Data was prospectively collected and retrospectively analysed for 816 hip fracture patients. Multivariate logistic regression was carried out on 3 binary outcomes (time-to-surgery < 36 h; 30-d mortality; 120-d mortality), using the explanatory variables time-of-admission; age; gender; American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) grade; abbreviated mental test score (AMTS); fracture type; accommodation admitted from; walking ability outdoors; accompaniment outdoors and season.

Baseline characteristics were not statistically different between those admitted on weekdays vs weekends. Weekend admission was not associated with an increased time-to-surgery (P = 0.975), 30-d mortality (P = 0.842) or 120-d mortality (P = 0.425). Gender (P = 0.028), ASA grade (P < 0.001), AMTS (P = 0.041) and accompaniment outdoors (P = 0.033) were significant co-variates for 30-d mortality. Furthermore, age (P < 0.001), gender (P = 0.011), ASA grade (P < 0.001), AMTS (P < 0.001) and accompaniment outdoors (P = 0.033) all significantly influenced mortality at 120 d. ASA (P < 0.001) and season (P = 0.014) had significant effect on the odds of undergoing surgery in under 36 h.

Weekend admission was not associated with increased time-to-surgery or mortality in hip fracture patients. Demographic factors affect mortality in accordance with previous published reports.

Core tip: The weekend effect is gaining academic and political interest. It is important to consider departmental set ups that avoid potentially increased mortality in sick patients admitted on the weekend. Here we evaluate hip fracture patients admitted to a United Kingdom teaching hospital prior to the recent media and political interest, in a centre that had been commended for its care of hip fracture patients. There is no increased mortality in those admitted on a weekend - confirming that it is possible to negate a “weekend effect” with the appropriate infrastructure for hip fracture patients.

- Citation: Mathews JA, Vindlacheruvu M, Khanduja V. Is there a weekend effect in hip fracture patients presenting to a United Kingdom teaching hospital? World J Orthop 2016; 7(10): 678-686

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i10/678.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.678

Hip fractures related to fragility account for a significant clinical and economic burden on the NHS, especially in an ageing population. There are an estimated 70000 such fractures annually in the United Kingdom, commanding a cost of almost £2 billion a year[1]. These patients have a high prevalence of co-morbidities reflected by the high level of mortality associated with hip fractures - up to 10% of patients die within 30 d[2]. In recent years there have been many steps taken to optimise the quality of care in this group of patients. This includes the distribution of the joint British Orthopaedic Association (BOA)-British Geriatric Society (BGS) “blue book”[1], the setting up of the United Kingdom National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD)[3], the government initiative of a best practice tariff (BPT)[4], and recent publication of NICE guideline CG124[5].

The literature has highlighted some concern over the management of patients admitted over weekends, which represent periods of time involving lower staffing levels and potential shortfalls in care[6]. North American and Australasian studies have found patients with certain medical and surgical diagnoses admitted over the weekend had higher risk-adjusted mortality than patients admitted on weekdays[6-8]. This potential “weekend effect” may be exaggerated in teaching hospitals[7]. In addition, a recent Dr. Foster report suggested that within the United Kingdom, “access to treatment over a weekend is a weak link in the management of hip fractures”[9]. This observation must be addressed, as “early surgery” is associated with significantly reduced risk of mortality[10], and thus any delays linked to timing of admission may have important consequences.

Patients admitted with hip fracture often have multiple co-morbidities and can present with concomitant medical pathologies such as ischaemic heart disease, electrolyte imbalances, renal impairment and sepsis. The effective management of these, medical optimisation and access to timely surgery are key factors in the effective treatment of hip fractures and prevention of further complications. Thus, the objective of our study was to examine the potential “weekend effect” on patients presenting with acute fragility hip fracture to a United Kingdom teaching hospital. Our aim was to compare patients admitted on weekdays vs weekends to elucidate any differences in: (1) Time-to-surgery (within 36 h, or not); (2) 30-d mortality; and (3) 120-d mortality.

Our null hypothesis was that there would be no difference in time to surgery or mortality between weekday and weekend groups. In addition, we planned to analyse the effect of 9 other variables on the above outcomes: Age; gender; American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) grade; abbreviated mental test score (AMTS); fracture type; type of accommodation admitted from; walking ability outdoors; need for accompaniment outdoors and season.

Between 1st April 2009 and 30th September 2011, 883 patients were admitted to our hospital with primary fragility hip fracture. Hip fracture was defined as “a fracture occurring in the area between the edge of the femoral head and 5 cm below the lesser trochanter”. All these patients had detailed records prospectively created on the NHFD. We excluded those whose records were incomplete to avoid unknown confounders (missing data included details on where the patient was admitted from, preoperative mobility and cognitive status and adequate follow up). This left us a study sample of 816 patients with 100% complete datasets, who were all included in our study. The NHFD is an internet-based audit tool that collates a variety of details on patients admitted with acute hip fracture, including patient characteristics, fracture type, operative details and times of admission to A&E, admission to orthopaedic ward and time of surgery. Accurate dates of death were attained from electronic hospital patient records. The resulting dataset was then used to extrapolate accurate values for time-to-surgery (hours) and 30- and 120-d mortality rates. Of the 816 patients, 20 did not have surgery and thus were excluded from the analysis for time-to-surgery (n = 796).

Patients who were admitted to A and E from Monday 8:00 AM and Friday 5:59 PM were placed in the “weekday” group. Those admitted between Friday 6:00 PM and Monday 7:59 AM were categorised as the “weekend” group, in line with the trust out-of-hours rota.

Baseline characteristics between the two groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test (for categorical co-variates) or Mann - Whitney U test (for continuous co-variates).

Logistic regression was carried out on 3 outcomes of interest (all binary outcomes), using 10 explanatory variables: (1) the proportion of patients receiving surgery in less than 36 h; (2) 30-d mortality; and (3) 120-d mortality.

The co-variates used were: day of admission (weekday vs weekend); age; gender; ASA grade; AMTS; type of accommodation admitted from; type of fracture; ability to walk outdoors, need for accompaniment outdoors and season. Logistic regression models were fitted and the “Enter” method was used in the regression models to incorporate the time of week variable, as this was the main interest of the study; forward model selection was then applied to the remaining nine covariates in order to select the most parsimonious model. A P-value < 0.05 was considered as significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Rebecca Harvey of the Centre for Applied Medical Statistics, University of Cambridge.

A total of 796 patients were included for the final analysis. The average age of these patients was 83.0 ± 8.7 years, with a gender ratio of 2.5:1 (581 females; 235 males). During the study period there were 581 admissions during weekdays and 235 during weekend periods. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were not statistically different in any of the measured fields (Table 1). The most common type of fracture seen during our study period was the intracapsular and displaced neck of femur fracture (n = 386; 47.9%). Most patients (n = 662; 70.9%) were living in their own home and around a third (n = 290; 35.6%) of patients walked outdoors without the use of aids prior to injury.

| Explanatory variable | Classification | Time of week | |

| Weekday | Weekend | ||

| Age, yr mean (SD) | 46.4-100.9 (P = 0.779)2 | 83.1 (8.4) | 82.6 (9.3) |

| Gender | Male | 169 | 65 |

| Female | 412 | 170 | |

| (Female %) (P = 0.733)1 | (70.90%) | (72.30%) | |

| ASA grade median (IQR) | 1-5 (P = 0.282)2 | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| AMTS median (IQR) | 0-10 (P = 0.924)2 | 8 (5) | 8 (5) |

| Fracture type | Intertrochanteric | 217 | 92 |

| Intracapsular - displaced | 287 | 99 | |

| Intracapsular - undisplaced | 48 | 31 | |

| Subtrochanteric | 29 | 13 | |

| (% Intracapsular-displaced) (P = 0.097)1 | (49.40%) | (42.10%) | |

| Admitted from | Own home | 417 | 191 |

| Other | 110 | 44 | |

| (% Own home) (P = 1.00)1 | (81.10%) | (81.30%) | |

| Ability to walk outdoors | Wheelchair/bedbound/electric buggy | 173 | 65 |

| Never goes outdoors | |||

| Two aids | 54 | 20 | |

| One aids | 154 | 60 | |

| No aids | 200 | 90 | |

| (% Wheelchair, etc.) (P = 0.780)1 | (29.80%) | (27.70%) | |

| Accompaniment outdoors | Wheelchair/bedbound/electric buggy | 88 | 31 |

| Never goes outdoors | |||

| Yes | 193 | 86 | |

| No | 300 | 118 | |

| (% Wheelchair, etc.) (P = 0.604)1 | (15.10%) | (13.20%) | |

| Season | Spring | 133 | 61 |

| Summer | 183 | 54 | |

| Autumn | 160 | 73 | |

| Winter | 105 | 47 | |

| (% Winter) (P = 0.108)1 | (18.10%) | (20.00%) | |

| Time of week | Weekday | 581 | 0 |

| Weekend | 0 | 235 | |

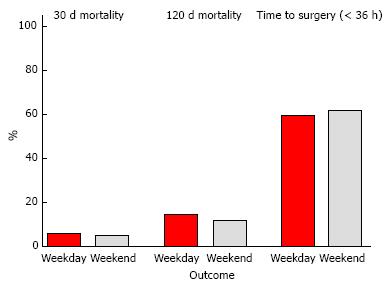

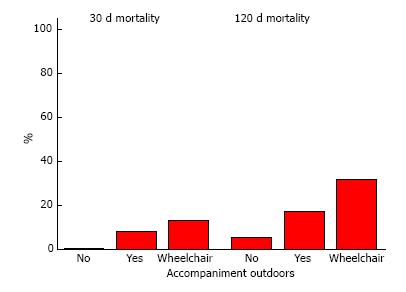

None of the outcome measures were significantly different between the weekday and the weekend groups (Figure 1 and Table 2).

| Outcome variable | Classification | Time of week | |

| Weekday | Weekend | ||

| Time to surgery | < 36 h | 334 | 138 |

| (n = 796) | > 36 h | 233 | 91 |

| (%< 36 h) P > 0.05 | (58.90%) | (60.30%) | |

| 30-d mortality | No | 548 | 224 |

| (n = 816) | Yes | 33 | 11 |

| (%Yes) P > 0.05 | (5.70%) | (4.70%) | |

| 120-d mortality | No | 497 | 207 |

| (n = 816) | Yes | 84 | 28 |

| (%Yes) P > 0.05 | (14.50%) | (13.50%) | |

| Outcome 1 | Time to surgery (< 36 h) | n = 796 | ||

| Variable | Level | OR | 95%CI | P-value |

| ASA grade | 1-5 | 0.68 | 0.54, 0.85 | 0.001 |

| Season | Winter (reference) | 0.014 | ||

| Spring | 1.89 | 1.21, 2.94 | 0.005 | |

| Summer | 1.7 | 1.11, 2.61 | 0.014 | |

| Autumn | 1.9 | 1.23, 2.92 | 0.004 | |

| Time of week | Weekday (reference) | |||

| Weekend | 1.01 | 0.73, 1.39 | 0.975 | |

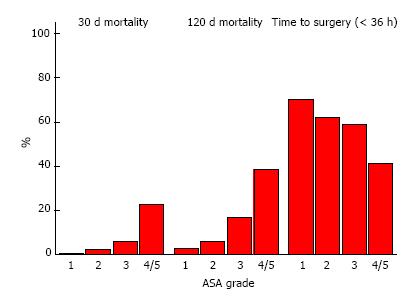

There was statistically no difference in the odds of time-to-surgery being less than 36 h between weekend and weekday patients (P = 0.975). As ASA increases by one unit, the expected odds of having a time-to-surgery of less than 36 h are reduced by 32% (P = 0.001; 95%CI: 0.54, 0.85) (Figure 2). The season also has a significant effect on undergoing surgery within 36 h (P = 0.014). Patients who were admitted in spring, summer or autumn all have greater odds of having a time to surgery of less than 36 h compared to the patients admitted in winter.

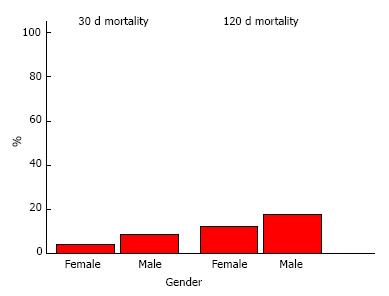

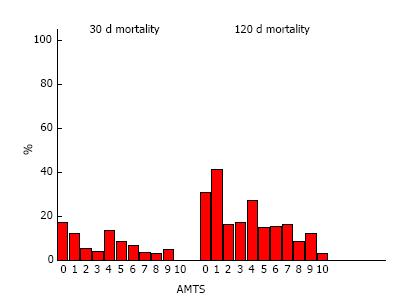

There was statistically no difference in the odds of mortality within 30 d between hip fracture patients admitted during the weekdays vs weekends (P = 0.842) (Table 4). ASA was a strongly significant covariate in this model. As ASA grade increases by one unit, it is expected that the odds of dying by 30 d to be almost 2.7 times greater (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Male patients had higher odds of mortality at 30 d than female patients [odds ratio (OR) 2.12; 95%CI: 1.09, 4.15] (Figure 3). It is expected that the 30-d mortality odds are lower as AMTS increases by one unit (P = 0.041); as AMTS increases by 1, the odds of dying at 30 d are reduced by 10% (95%CI: 0.81, 1.00) (Figure 4). Patients requiring accompaniment outdoors (P = 0.015) and those using a wheelchair or never go outdoors (P = 0.011) both have higher odds of mortality at 30 d compared with those who do not need any accompaniment outside (Figure 5). Wheelchair-bound patients have the greatest odds relative to those not requiring accompaniment outdoors - they are expected to have 5 times the odds of 30-d mortality. Other co-variates were not significant on this outcome.

| Outcome 2 30-d mortality | n = 816 | Outcome 3 120-d mortality | n = 816 | |||||

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | P-value | OR | 95%CI | P-value | ||

| Gender | Female (reference) | Female (reference) | ||||||

| Male | 2.12 | 1.09, 4.15 | 0.028 | Male | 1.86 | 1.15, 2.99 | 0.011 | |

| ASA grade | 1-5 | 2.68 | 1.55, 4.62 | < 0.001 | 1-5 | 2.03 | 1.39, 2.95 | < 0.001 |

| AMTS | 0-10 | 0.9 | 0.81, 1.00 | 0.041 | 0-10 | 0.89 | 0.83, 0.95 | 0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 46-101 | 1.06 | 1.03, 1.10 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Accompanied | No (reference) | 0.033 | No (reference) | 0.033 | ||||

| outdoors | Yes | 4.22 | 1.32, 13.47 | 0.015 | Yes | 1.29 | 0.70, 2.36 | 0.423 |

| Wheelchair/bedbound/electric buggy/does not go out | 5.14 | 1.46, 18.09 | 0.011 | Wheelchair/bedbound/electric buggy/does not go out | 2.22 | 1.12, 4.38 | 0.022 | |

| Time of week | Weekday (reference) | Weekday (reference) | ||||||

| Weekend | 0.93 | 0.44, 1.94 | 0.842 | weekend | 0.82 | 0.50, 1.34 | 0.425 | |

There is no difference in odds of 120-d mortality between the weekend and the weekday groups (P-value = 0.425) (Table 4). As ASA increases by one unit, we would expect the odds of 120-d mortality to be 2 times greater (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). At 120 d, male patients have greater odds of dying but the expected increase in odds is lower than at 30 d. Male patients are expected to have 1.85 greater odds of mortality at 120 d (95%CI: 1.15, 2.98) (Figure 3). As AMTS increases by a unit, it would be expected that the odds of death at 120 d decrease by around 11% (P = 0.001) (Figure 4).

As age increases by one year, the odds of dying at 120 d are 1.06 times greater, i.e., an age increase of one year yields a 6% increase in 120-d mortality (95%CI: 1.03, 1.10). Patients who require a wheelchair to go outdoors or patients who don’t go outside have more than twice the odds of 120-d mortality than patients who don’t need accompaniment outdoors (P = 0.022) (Figure 5). There is however statistically no difference in odds of dying between non wheelchair bound patients who need accompaniment outdoors and patients who do not require accompaniment outdoors. Other co-variates were not significant on this outcome

This study examines the potential weekend effect in patients with a hip fracture in a single teaching hospital within the United Kingdom; it reveals no statistical difference in either 30- or 120-d mortality between patients admitted to our tertiary referral hospital on weekdays vs weekends. In addition, patients admitted on the weekend were equally likely to undergo surgery within 36 h.

Hip fractures represent a common and serious injury in older people. Surgery is the main stay of treatment, with over 98% of patients undergoing operative fixation[3]. The association of early surgery with lower mortality rates in these patients has been widely published[10]. Whilst national NICE guidelines recommend that surgery be performed “on the day of, or the day after admission”[5], the government has introduced the “BPT”[4]. The BPT offers hospitals a £1335 “bonus” payment per hip fracture patient that is managed according to a set of quality indicators, which include performing surgery within 36 h of admission, in combination with orthogeriatric led medical care in the acute phase and secondary fracture prevention. The BPT aims to financially incentivise best clinical practice in hip fracture management and thus enable targeted investment back into local hip fracture services. Accordingly, it has become a target for orthopaedic departments across the country to achieve surgery within the 36-h window and thus we chose that cut-off for this study.

Admissions over the weekend and other out-of-hour periods have been associated with undesirable delays in investigations and procedures for certain conditions. A report recently published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) suggested that patients admitted over the weekend in the United States had significantly longer waits for various major procedures[11]. The 2011 Dr. Foster report highlighted that there may be significant delays to hip fracture surgery associated with timing of admission in the United Kingdom, highlighting that many trusts are significantly worse at operating at the weekend[9].

In addition, past research has shown that weekend admission is associated with increased mortality in certain diagnoses, attributing their findings to lower staffing levels and unreliable access to clinical services. Studies from Canada, United States and Australia have shown patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)[6], pulmonary embolism[6], duodenal ulcers[7] and ischaemic heart disease[7,8] have a significantly increased risk of mortality if admitted during the weekend rather than weekday. More recently, evidence of a weekend effect for emergency conditions has also been reported in the United Kingdom[12]. These studies did not observe an increase in mortality in hip fracture patients. However, a Danish study looking at 600 patients presenting with acute hip fracture, did find a significantly higher rate of mortality for those admitted over holiday periods[13], another time group with limitations in human resources. One previous study has observed a potential weekend effect for hip fracture patients in a different United Kingdom teaching hospital[14]. However, following reports of no weekend effect at national level in the United States[15], it was clear that this may not be the case at other similar United Kingdom institutions and it is essential that this is shown.

Our data shows that being admitted with a hip fracture on the weekend has no negative impact on whether patients undergo surgery within 36 h, at our centre. This is likely to be due to the fact this hospital runs a dedicated trauma list, with an allocated anaesthetist and on call theatre radiographer 7 d/wk. In centres where this in not available, the potential improvement in surgical delay with the addition of extra trauma theatre time has been emphasized[16,17]. In addition we have a trauma nurse specialist heavily involved with the management of patients and organisation of trauma lists on every Saturday, in addition to weekdays. Despite these resources available, we found that around 16% of our cases are still delayed whilst awaiting trauma list space underlining the considerable room for further improvement[3]. Indeed, only around 60% of patients achieve surgery within 36 h - however, this is a relatively new target that was introduced in April 2010, and the NHFD report shows this number to be improving nationwide since then[3].

Our study also reveals an inverse relationship between the ASA grade and the time to surgery. This probably translates to patients with more co-morbidities requiring longer to undergo appropriate tests prior to transfer and achieve pre-operative optimization. Indeed, the NHFD report for 2010-2011 suggested that almost 1/3 of the fragility hip fracture patients in the United Kingdom who did not receive an operation within 36 h were delayed because they were awaiting medical review, investigation or stabilization[3]. The number of patients falling into this group may be greater on weekends in some smaller United Kingdom centres where there are potentially only one or two general medical registrars on site; our centre is fortunate to have subspeciality medical registrars (e.g., cardiology, respiratory) on call as well during the weekends. Thus speciality review and special investigations may have a greater probability of being achieved on admission, which could reduce potential delays in optimisation for surgery.

Interestingly, we found that patients admitted during spring, summer or autumn were statistically more likely to go for surgery within 36 h than those who presented in winter. Higher fracture rates during winter have been reported for various types fracture in the United Kingdom, including hip fractures[18,19]. It may be that patients admitted with hip fracture over winter are more likely to have an acute medical illness which has predisposed them to an increase risk of falls. Additionally, adverse weather conditions may have led to an increase in other non hip fractures, which may be reflected by longer time-to-surgery for patients in our study.

Our model did not find any significant difference in 30- or 120-d mortality between those admitted on weekends when compared with weekday admissions, supporting the null hypothesis. However, logistic regression of our data revealed that patients who were older, male, or had a higher ASA grade or lower AMTS at admission had a significantly higher risk of mortality, which correlates with previous observations[20]. In addition, those who were wheelchair bound or did not go outside had a significantly increased odd of mortality, which may reflect the severity of co-morbidities in these patients. Baseline characteristics were not different between the two groups. Early surgery following hip fracture has been shown to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality when compared with delayed surgery[13]. Thus, the fact there was no statistical difference between weekday and weekend groups in time-to-surgery within 36 h, nor mortality, suggests the outcomes are likely to be linked in our study. Whilst significant blood loss following hip fracture has been reported[21], and such injuries may occur as a result of cardiorespiratory deterioration, it is not a diagnosis that is as susceptible to delays in definitive treatment as those mentioned above that do exhibit a weekend effect. These diagnoses, such as ruptured AAA, PE, and MI would be expected to have a much faster, more dramatic effect on haemodynamic stability.

Our data reveals that the overall 30-d mortality for patients presenting with hip fractures to our unit between April 2009-September 2011 was 5.4%. This is notably better than the widely reported figure of 10%[3]; this lower rate has been previously acknowledged and commended[22]. We have an established orthogeriatric service which directs peri- and post-operative medical optimisation of these patients. Regular medical input by such a team allows a continuity of care not afforded by previous systems where issues were dealt with by the on-call medical registrar of the day. In addition, our multidisciplinary rehabilitation team includes regular input from trauma nurse specialists, and 7 d/wk physiotherapy and occupational therapy service, with emphasis placed on providing falls assessment and commencing bone protection medication during the admission. This highlights the potential positives of adhering to the indicators set out by the BPT[4].

The aim of the BPT, which offers £1335 more than base tariff per case, is to financially incentivise best clinical practice in hip fracture management and thus enable targeted investment back into local hip fracture services. This should “stimulate better quality service provision which is more cost effective”[4]. Our findings suggest that such funding would be well spent in developing additional trauma theatre time and further enhancing services over the weekend including physiotherapy, orthogeriatrics, trauma anaesthetists and theatre radiographers. Whilst guidelines encourage surgery to be performed during “normal working hours”, there may be an argument to routinely extend the length of trauma lists to the twilight period to achieve better outcomes and aid qualification for the economic incentive described above.

Our study does have limitations. The NHFD is an internet-based data collection system that was set up in 2007 following the long term success of databases such as the Scottish Hip fracture audit[23]. It collates a wealth of information making it a powerful clinical audit tool, especially as data is collected prospectively. As with any database the information available is subject to error during data entry. Some fields such as were missing for certain patients resulting in exclusion of patients from our study. Importantly, baseline characteristics were not statistically different between weekday and weekend groups, either prior to or following exclusion though. The risk of future missing data has been minimised by appointment of an elderly trauma nurse specialist whose role includes ensuring accuracy, appropriateness and completeness of database entries.

We chose to maximise the number of patients we could analyse by including all patients who we could ascertain 120-d mortality data. In addition, it was necessary to amalgamate some groups to allow analysis, as individual groups (e.g., those with ASA 4 or 5) would not have contained sufficient patients otherwise. Future studies should aim to explore if any difference exists in the longer term, for instance at 1 year, and should be of sufficient size to have adequate numbers in each category for analysis.

The management of hip fracture and resources available at different trusts vary considerably; it was the recognition of this fact which initiated the immense nationwide effort towards clinical governance outlined in this paper. Accordingly, it would be naïve to infer that the findings described at our tertiary referral centre hold true for all other hospitals in the United Kingdom. Previous studies have suggested that weekend effects are amplified in teaching hospitals[7]. This may not be the case in hip fracture surgery, if indeed there is a weekend effect to be found in other hospitals. The NHFD does however represent a useful instrument with which to analyse this potential weekend effect on a national basis, perhaps including a comparison between outcomes at teaching vs district general hospitals, as has previously been done in other countries[7].

We would like to give special thanks to Jane Hall, who helped collect the local data for the NHFD. We are also grateful to Rebecca Harvey for helping us with the data analysis and interpretation, using her expertise in medical statistics.

The weekend effect is gaining academic and political interest. Here we evaluate hip fracture patients admitted to a United Kingdom teaching hospital prior to the recent media and political interest, in a centre that had been commended for its care of hip fracture patients. Departments in the United Kingdom are encouraged to aim to medically optimise and operate on all hip fracture patients within 36 h if medically stable. However, hospitals around the country are very heterogeneous in their infrastructure. It is important to consider departmental set ups that avoid potentially increased mortality in sick patients admitted on the weekend.

The weekend effect refers to the differential on mortality between patients admitted on a weekday with a given diagnosis, when compared with those admitted on a weekend with the same diagnosis. It is encouraged that hip fracture patients are operated on within 36 h of admission in the United Kingdom. This is financially incentivized as this time target is one of the criteria for the best practice tariff (BPT) (see terminology).

Whilst large population studies are incredibly useful at exploring the presence of weekend effect within a whole system, it is also important to check for its presence within heterogeneous departments within that overall system. This allows comparison and elucidation of potential targets to attenuate such differences. This study shows no weekend effect at this United Kingdom teaching hospital for hip fracture patients, in contrast with findings from other teaching hospitals. Increased orthogeriatrics involvement and 7 d/wk orthopaedic trauma lists are likely factors that negate the weekend effect.

Departments should explore the weekend effect in their departments to highlight areas for service improvement.

BPT - the United Kingdom government has introduced the BPT. The BPT offers hospitals a £1335 “bonus” payment per hip fracture patient that is managed according to a set of quality indicators, which include performing surgery within 36 h of admission, in combination with orthogeriatric led medical care in the acute phase and secondary fracture prevention. The BPT aims to financially incentivise best clinical practice in hip fracture management and thus enable targeted investment back into local hip fracture services.

Authors compared mortality and time-to-surgery of patients admitted with hip fracture to their teaching hospital on weekdays vs weekends. As an observational report, it is an interesting study of weekend effect on hip fracture patients. Experiments are generally well conducted and the manuscript is well written.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kuiper JWP, Maheshwari AV, Song GB S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | The care of patients with a fragility fracture. Published by the British Orthopaedic Association, 2007. [accessed 2011 Nov 21]. Available from: http://www.fractures.com/pdf/BOA-BGS-Blue-Book.pdf. |

| 2. | Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331:1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 970] [Cited by in RCA: 1017] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | The National Hip Fracture Database National Report 2011. [accessed 2011 Dec 4]. Available from: http://www.nhfd.co.uk/003/hipfracrureR.nsf/NHFDNationalReport2011_Final.pdf. |

| 4. | Best Practice Tariff for Hip Fracture- Making ends meet. British Geriatrics Society. [accessed 2011 Nov 28]. Available from: http://www.bgs.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=700: tariffhipfracture&catid=47: fallsandbones&Itemid=307. |

| 5. | Hip fracture: the management of hip fracture in adults. NICE clinical guideline CG124; issued June 2011. [accessed 2011 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13489/54919/54919.pdf. |

| 6. | Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 779] [Cited by in RCA: 837] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Clarke MS, Wills RA, Bowman RV, Zimmerman PV, Fong KM, Coory MD, Yang IA. Exploratory study of the ‘weekend effect’ for acute medical admissions to public hospitals in Queensland, Australia. Intern Med J. 2010;40:777-783. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Inside your hospital - Dr Foster Hospital Guide 2001-2011. [accessed 2011 Dec 7]. Available from: http://drfosterintelligence.co.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2011/11/Hospital_Guide_2011.pdf. |

| 10. | Simunovic N, Devereaux PJ, Sprague S, Guyatt GH, Schemitsch E, Debeer J, Bhandari M. Effect of early surgery after hip fracture on mortality and complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2010;182:1609-1616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in RCA: 644] [Article Influence: 42.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ryan K, Levit K, Hannah Davis PH. Characteristics of Weekday and Weekend Hospital Admissions. Rockville, MD, HCUP Statistical Brief #87. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006- 2010; Mar. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, Ray D, Khosla S, Shahian D, Roche WR, Stephens I, Keogh B, Pagano D. Weekend hospitalization and additional risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. J R Soc Med. 2012;105:74-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Foss NB, Kehlet H. Short-term mortality in hip fracture patients admitted during weekends and holidays. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:450-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thomas CJ, Smith RP, Uzoigwe CE, Braybrooke JR. The weekend effect: short-term mortality following admission with a hip fracture. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:373-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Boylan MR, Rosenbaum J, Adler A, Naziri Q, Paulino CB. Hip Fracture and the Weekend Effect: Does Weekend Admission Affect Patient Outcomes? Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44:458-464. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Marsland D, Chadwick C. Prospective study of surgical delay for hip fractures: impact of an orthogeriatrician and increased trauma capacity. Int Orthop. 2010;34:1277-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bhattacharyya T, Vrahas MS, Morrison SM, Kim E, Wiklund RA, Smith RM, Rubash HE. The value of the dedicated orthopaedic trauma operating room. J Trauma. 2006;60:1336-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Crawford JR, Parker MJ. Seasonal variation of proximal femoral fractures in the United Kingdom. Injury. 2003;34:223-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | O'Neill TW, Cooper C, Finn JD, Lunt M, Purdie D, Reid DM, Rowe R, Woolf AD, Wallace WA. Incidence of distal forearm fracture in British men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:555-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gunasekera N, Boulton C, Morris C, Moran C. Hip fracture audit: the Nottingham experience. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:S647-S653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Smith GH, Tsang J, Molyneux SG, White TO. The hidden blood loss after hip fracture. Injury. 2011;42:133-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hospital Guide 2010: What makes a good hospital. [accessed 2011 Nov 28]. Available from: http://www.drfosterhealth.co.uk/docs/ospital-guide-2010.pdf. |

| 23. | Scottish Hip fracture Audit: Report 2008. Information and statistics division NHS services Scotland. [accessed 2012 Jan 12]. Available from: http://www.show.scot.nhs.uk/shfa. |