Published online Oct 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.650

Peer-review started: April 24, 2016

First decision: June 6, 2016

Revised: July 15, 2016

Accepted: August 6, 2016

Article in press: August 8, 2016

Published online: October 18, 2016

Processing time: 172 Days and 4.8 Hours

Ulnar nerve (UN) injuries are a common complaint amongst overhead athletes. The UN is strained during periods of extreme valgus stress at the elbow, especially in the late-cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing. Although early ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) reconstruction techniques frequently included routine submuscular UN transposition, this is becoming less common with more modern techniques. We review the recent literature on the sites of UN compression, techniques to evaluate the UN nerve, and treatment of UN pathology in the overhead athlete. We also discuss our preferred techniques for selective decompression and anterior transposition of the UN when indicated. More recent studies support the use of UN transpositions only when there are specific preoperative symptoms. Athletes with isolated ulnar neuropathy are increasingly being treated with subcutaneous anterior transposition of the nerve rather than submuscular transposition. When ulnar neuropathy occurs with UCL insufficiency, adoption of the muscle-splitting approach for UCL reconstructions, as well as using a subcutaneous UN transposition have led to fewer postoperative complications and improved outcomes. Prudent handling of the UN in addition to appropriate surgical technique can lead to a high percentage of athletes who return to competitive sports following surgery for ulnar neuropathy.

Core tip: Ulnar nerve (UN) injuries frequently plague overhead athletes due to the strain caused by extreme valgus stress across the elbow during throwing. In this paper, we review common locations of UN compression and keys to the evaluation. We also discuss the recent literature on treatment of injuries to the UN in overhead athletes and our preferred techniques for addressing UN symptomatology during concomitant UCL reconstruction. Athletes are increasingly being treated with subcutaneous anterior UN transpositions only when appreciable neurologic symptoms are present preoperatively.

- Citation: Conti MS, Camp CL, Elattrache NS, Altchek DW, Dines JS. Treatment of the ulnar nerve for overhead throwing athletes undergoing ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. World J Orthop 2016; 7(10): 650-656

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i10/650.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.650

Ulnar nerve (UN) injuries in the overhead athlete often occur as a result of overuse of the arm during throwing and may exist in isolation or in association with other pathologic processes such as ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) insufficiency[1-4]. Because of its course along the medial elbow, the UN can be strained in the cubital tunnel (CT) secondary to the extreme valgus stress experienced by the elbow during throwing[1,2]. Secondary causes of ulnar neuropathy include a traction neuritis as a result of valgus stress, osteophytes, compression caused by adhesions, flexor muscle hypertrophy, or repetitive friction secondary to subluxation of the nerve[5]. As the second most common entrapment neuropathy of the upper extremity, CT syndrome (CTS) has even been reported in adolescent baseball players in elementary and middle school[6,7].

Reconstruction of the UCL also places the UN at risk. When Dr. Jobe et al[8] first published his series of UCL reconstructions with concomitant submuscular UN transposition in 16 elite throwing athletes in 1986, he reported postoperative UN complications in five patients, of which, two required a subsequent surgery for neurolysis. However, changes in surgical technique including selective, subcutaneous transposition of the UN have led to improved outcomes in UCL reconstruction and fewer postoperative neurologic complications[5,9].

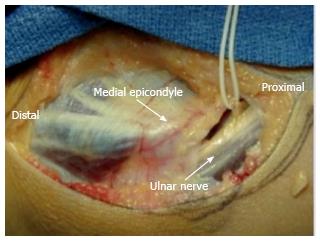

The UN begins in the anterior compartment of the upper arm before entering the posterior compartment at the arcade of Struthers. At the elbow, the nerve resides in the CT just posterior to the medial epicondyle and exits the CT between the dual heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (FCU) and into the anterior compartment of the forearm (Figure 1). Nerve compression may occur at numerous sites throughout its course. Additionally, the UN is susceptible to the “double crush” phenomenon, which is found when the it is compressed at more than one level[10]. This occurs because nerves compressed at one site are more easily damaged at another[11].

The arcade of Struthers, a band that travels from the medial head of the triceps to the medial intermuscular septum in the upper arm, is another common site of compression for the UN. Located approximately 8 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle, the arcade of Struthers present in 70% of the population[3,9,12,13]. Failure to relieve compression at the arcade of Struthers can lead to persistent UN symptoms despite cubital tunnel release[3,9,10,12,13]. The UN can also be compressed in patients with a hypertrophy medial triceps, which is commonly observed in throwing atheltes[9]. In a recent series of six adolescent throwers with CTS and a hypertrophic medial triceps, all six patients demonstrated UN compression when the elbow was flexed greater than 90°[7].

After traversing the arcade of Struthers, the nerve enters the CT as it passes behind the medial epicondyle. The floor of the CT is formed by the olecranon, posteromedial elbow capsule, and UCL, while the roof is created by the CT retinaculum (or arcuate ligament). It has been reported that the space available for the UN within the CT decreases by as much as 55% during elbow flexion[10]. Additionally, the CT can be narrowed in the presence of a hypertrophic arcuate ligament or anconeus epitrochlearis muscle[9,14]. Bony abnormalities such as prominent osteophytes near the medial epicondyle or the olecranon can impinge on the nerve in the CT resulting in UN irritation[9].

Upon exiting the CT, the UN passes between the dual muscle bellies of the FCU. Compression can also occur at the aponeurosis of the FCU. Additionally, repetitive microtrauma can lead to osteophyte formation and hypertrophy of the sublime tubercle at the UCL insertion, which can subsequently compress the nerve at this site[9].

UN hypermobility leading to subluxation or dislocation anteriorly over the medial epicondyle may also produce symptoms[6,9]. Subluxation of the UN typically occurs during elbow flexion[6]. Asymptomatic nerve dislocation has been reported in 16% of individuals[15]. Chronic friction as a result of repeated subluxations of the UN in overhead athletes may lead to inflammation and neuropathy[16].

The valgus stress experienced by the elbow during overhead throwing may also lead to traction neuropathy of the UN. During late-cocking and early acceleration, the valgus force at the elbow has been estimated to be well over 60 N*m with compressive forces exceeding 500 N at the radiocapitellar joint[17]. This valgus stress, in combination with elbow extension, results in a tensile stress across structures of the medial elbow including the UCL and UN[5]. Repetitive microtrauma to the UCL can eventually lead to attenuation or failure of the ligament[5]. The laxity caused by UCL insufficiency may permit increased medial soft tissue stretching that predisposes these athletes to ulnar neuritis[5]. Aoki et al[18] found that the maximum strain during the acceleration phase of throwing may lead to nerve injury and compromise its vascular supply. The resultant decreased circulation to the nerve during overhead throwing may be an important factor contributing to ulnar neuropathy.

Additionally, traction on the UN that occurs when the extended elbow is flexed may contributed to nerve injury[10]. An additional 5.1 mm of UN excursion has been reported as the elbow moves from 10 to 90 degrees[19]. This longitudinal traction may compromise neural function and increase the likelihood of irritation[10].

The diagnosis of ulnar neuropathy in the overhead athlete is predominantly based on history and exam. Early symptoms may include diminished sensation, tingling, or a burning type sensation in the small and ring fingers, especially during or after throwing[5,9]. Elbow flexion may also exacerbate the patient’s symptoms[6]. Athletes may endorse pain along the medial elbow and limitation of elbow extension despite prolonged periods of rest[7]. Motor symptoms including weakness or atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand are typically late findings seen only in severe or chronic cases[9]. Symptoms are generally worsened by repetitive valgus stress, and after several innings of throwing, pitchers may complain of heaviness or clumsiness of the hands and fingers[9]. Patients who suffer from UN subluxation may report a snapping or popping sensation at the medial elbow that occurs with flexion, extension, or throwing[9].

Physical examination in the throwing athlete must include the entire length of the UN. A thorough assessment of the cervical spine needs to be performed to look for evidence of radiculopathy or degenerative changes[9]. Neural or vascular compression at the thoracic outlet should also be ruled out. Afterwards, the examiner can shift focus to the medial elbow. Elbow instability as a result of UCL injury or insufficiency is an important underlying cause of ulnar neuritis[5]. Thus, UCL evaluation in athletes with suspected UN compression is essential. Valgus laxity should be assessed, and the Moving Valgus Stress Test is one the more reliable examination maneuvers for UCL insufficiency[5]. Palpation of the medial elbow may elicit UN tenderness in the cubital tunnel and may be useful to identify coexisting medial epicondylitis or UN subluxation out of the condylar groove, especially as the elbow is flexed and extended[9,10]. The examiner should ensure that any patient with a subluxating UN does not also have a snapping medial triceps[20]. This generally presents as a second “snap” that follows the nerve subluxation. Tinel’s test involves tapping the nerve from distal to proximal, and a positive test occurs when there is an unpleasant sensation at a site along the course of the nerve, especially if this recreates the patient’s symptoms[10]. In throwing athletes with suspected ulnar neuropathy, special attention should be directed towards the cubital tunnel[9]. In addition, the elbow flexion test is a provocative maneuver that can be used to reproduce UN symptoms. To perform the elbow flexion test, the elbow is flexed, while the forearm is supinated and the wrist is extended for several minutes[9]. The elbow flexion test is positive if the UN symptoms are aggravated in this position[9].

Distally, a full neurovascular examination should be performed. Loss of static two-point discrimination when compared to the contralateral hand, weakness in grip strength, and weakness in pinch strength can all be signs of ulnar neuropathy[7]. Froment’s sign, in which the patient grasps a piece of paper between the thumb and index finger while resisting the examiner’s attempt to pull the object from the patient’s hand, may be used to test UN function[10]. Weakness in the hand’s intrinsic muscles may be subtle but often presents before changes in forearm extrinsic weakness and grip strength[9].

Imaging should begin with elbow in multiple planes (anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views)[5]. X-rays are evaluated for osteophytes or degenerative changes that may impinge on the UN as well as any previous bony injury, loose bodies, or abnormal calcification[9]. Magnetic resonance imaging is often utilized to evaluate the soft tissue structures of the elbow such as: The UN, UCL, and possible space occupying lesions or bone spurs[9]. Electrophysiologic investigations may occasionally be useful to confirm the diagnosis and the location of compression in equivocal cases[10]. Additionally, electrodiagnostic testing may reveal a secondary compression site (“double crush” phenomenon). Because these studies have a false negative rate reported to be 10% or even higher, they cannot be solely relied on to identify ulnar neuropathy in the throwing athlete[16].

Initial management of ulnar neuropathy with conservative treatment is appropriate for the overhead throwing athlete[5]. Anti-inflammatory medications, cryotherapy, and physical therapy are the mainstays of non-operative treatment[5]. The athlete should be instructed to avoid throwing or any other activities that cause pain[5]. The elbow may be splinted, especially at night, for six weeks to immobilize the UN, and the cubital tunnel may be protected using an elbow pad to avoid pressure to the region[9]. Before returning to sport, deficiencies in throwing mechanics must be identified and corrected[9]. A gradual interval-throwing program is initiated, and a stretching program for the posterior capsule is often indicated[9]. Additionally, participation in a strength-training program focusing on dynamic elbow stabilizers is an important part of rehabilitation[9]. The athlete should be followed clinically for progression of symptoms. For patients who fail to demonstrate improvement following a comprehensive course of conservative management, surgical options may be considered.

Surgical options for ulnar neuropathy at the cubital tunnel include in situ decompression, subcutaneous anterior transposition, or in rare cases, submuscular transposition. UN entrapment syndrome was initially treated with submuscular anterior transposition, and Del Pizzo et al[21] demonstrated successful return to play at 3 to 58 mo postoperatively in nine of fifteen (60%) baseball players treated in this fashion. Similarly, the original technique for UCL reconstruction described by Dr. Jobe et al[8] consisted of release of the flexor-pronator mass from its insertion and concomitant UN submuscular transposition. However, of the sixteen elite throwing athletes included in the initial cohort, UN symptoms persisted in five patients post-operatively[8]. A follow-up series by Conway et al[22] of 71 athletes (including the sixteen athletes from the original study), who underwent UCL reconstruction and concomitant submuscular nerve transposition found postoperative ulnar neuropathy in 15 (21%) patients, and 9 of these patients went on to require further decompression surgery. Subsequent changes in surgical technique led to improved handling of the nerve and alterative strategies that did not require release of the flexor-pronator muscle origin[9].

Rettig and Ebben[23] demonstrated excellent outcomes with anterior subcutaneous UN transposition in twenty athletes who had failed non-operative treatment. The athletes were followed for an average of 19 mo postoperatively, and 19 of 20 (95%) patients were asymptomatic at that time[23]. The patients returned to play at an average of 12.6 wk[23]. Similarly, Andrews and Timmerman[24] published their results on an anterior subcutaneous transfer in eight professional athletes in 1995. They reported postoperative ulnar neuropathy in only 11% of cases, and seven of the athletes (88%) returned to their previous level of play for a minimum of one year[24]. Azar et al[25] reported only one case of postoperative transient ulnar neuropathy in 91 throwing athletes following UCL reconstruction and subcutaneous UN transposition. They found that 90% (9 of 10) of athletes with preoperative symptoms of ulnar neuritis demonstrated resolution of those symptoms postoperatively[25]. Another study in high school aged baseball players undergoing subcutaneous UN transposition reported a 7% incidence of transient ulnar neuropathy and 74% of these athletes were able to of return to their previous level of sport for at least a year[26]. Although no studies have directly compared subcutaneous and submuscular transposition of the UN, the reported rates of postoperative complications appear to be lower in the subcutaneous group.

More recently, many authors have recommended against obligatory UN transposition[1,27-29]. In one study of 83 athletes who underwent UCL reconstruction without nerve transposition, transient neurogenic symptoms were reported in only 4 (5%) patients post-operatively, and all resolved completely with non-operative care[27]. In this work, 20 (24%) patients had preoperative UN symptoms[27]. They hypothesized that not exposing or dissecting the UN minimized the risk of nerve injury[27]. Other authors only consider transposition of if neurologic symptoms are present preoperatively[28,29]. Koh et al[28] and Paletta et al[29] both reported low rates of postoperative UN complications (5% and 4%, respectively). Between the two studies, only one patient required subsequent UN transposition[28]. A more recent systematic review of 378 patients undergoing UCL reconstruction did not support obligatory UN transposition[1]. In this work, those treated with routine nerve transposition demonstrated a lower rate of “excellent” results (75% vs 89%) and were twice as likely to demonstrate signs of postoperative ulnar neuropathy compared with those treated without transposition[1]. However, some authors feel that in situ decompression should not be used in the overhead athlete because it fails to address the increased tension experienced during the throwing motion[9].

In patients without UN symptomatology, we do not routinely expose, decompress, or transpose the UN during UCL reconstruction. For the UCL reconstruction, we utilize the docking technique for humeral fixation and a muscle splitting approach to access the ligament[30]. Because the docking technique utilizes a socket on the humeral side, the in situ nerve is at less risk for injury than it would be when drilling full tunnels as described in the Modified Jobe technique. Great care is taken throughout the procedure to ensure that the course of the UN is well understood, and the nerve is protected during every step, especially during drilling. For patients with UN symptoms, we generally decompress and subcutaneously transpose the nerve during UCL reconstruction. Submuscular transposition is generally reserved for rare cases that have failed a prior subcutanetous transposition despite adequate proximal and distal decompression.

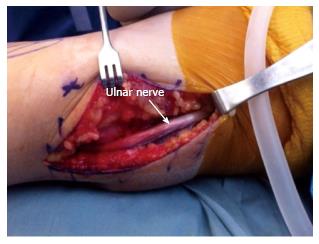

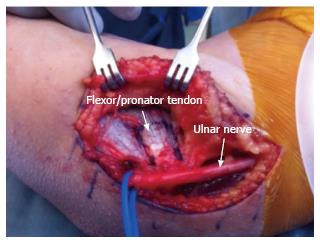

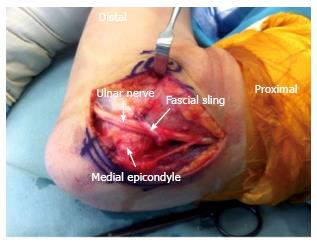

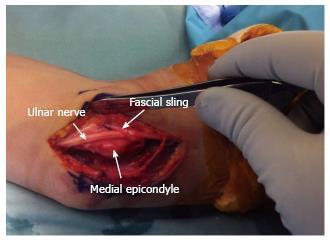

Subcutaneous transposition is accomplished using the V-sling technique as of Tan et al[31]. After identifying the UN posterior to the intermuscular septum and proximal to the cubital tunnel, it is carefully dissected free proximally and distally (Figure 2). If transposition is planned, we decompress the nerve at least 10 cm proximally and 10 cm distally from the elbow joint. The nerve is then protected until the UCL reconstruction is complete (Figure 3). Following the UCL procedure, the UN is transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle and thoroughly inspected for any sites of compression such as the medial triceps tendon proximally or the FCU fascia distally. Further decompression is completed as needed. Once it is completely free in the transposed position, a thin slip of the medial intermuscular septum is harvested to serve as a sling to hold it in place. This thin band is excised form the septal fascia beginning 8 cm above the epicondyle. It is dissected distally but is left attached at its distal insertion on the medial epicondyle. The strip is subsequently sutured to the flexor-pronator fascia in an inverted V-shape, which prevents the nerve from migrating behind the epicondyle (Figures 4 and 5).

The postoperative rehabilitation protocol following transposition of the UN with concomitant UCL reconstruction is determined by the reconstructive procedure rather than the nerve decompression. In these cases of UCL reconstruction, we place the patient in a split post-operatively. The splint is replaced with a hinged elbow brace one week following surgery. While wearing the brace, elbow ROM is initially permitted from 30° to 90°, and this is advanced to 15° to 105° from weeks 3 to 5. At week 6, the brace is discontinued, and formal physical therapy is initiated. From weeks 6 to 12, the focus of PT is on elbow ROM, and shoulder and wrist strength and ROM. This is advanced as tolerated. Beginning at 16th week, a formal throwing program is initiated if the patient has met all milestones up to this point. Throwing begins at a distance of 45 feet on flat ground and is slowly advanced as tolerated. If the patient is able to throw 180 feet on flat ground without pain at the 7- to 9-mo mark, throwing from the mound is permitted. This is slowly advanced over the next 3 mo with the goal of returning the athlete to competitive pitching from a mound between 12 and 18 mo.

Recent trends in the treatment of UN injuries in the overhead athlete favor reserving nerve decompression and transposition for instances in which there are appreciable UN symptoms present prior to surgery[1,27-29]. In cases of isolated ulnar neuropathy in athletes, in situ decompression or subcutaneous anterior transposition appear to have more favorable outcomes than submuscular transposition although the techniques have not yet been compared head to head. As the surgical approach for UCL reconstructions has evolved from flexor-pronator detachment to a more tissue friendly muscle-splitting approach, patients with UN symptoms who are undergoing UCL reconstruction are better suited with in situ decompression or subcutaneous transposition rather than submuscular transposition. These changes have led to fewer postoperative UN complications and improved outcomes in these high-demand athletes.

Because the UN lies in close proximity to the operative field during the UCL reconstruction, the surgeon must take great care to protect it throughout the duration of the case. Obtaining a diligent history, performing a detailed physical exam, and proper surgical technique are all critical steps needed to successfully treat throwing athletes with UN symptoms. When appropriate steps are followed, the vast majority of athletes can be expected to return to competitive sports.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Anand A, Patra SR S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Vitale MA, Ahmad CS. The outcome of elbow ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in overhead athletes: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1193-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | King JW, Brelsford HJ, Tullos HS. Analysis of the pitching arm of the professional baseball pitcher. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969;67:116-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Keefe DT, Lintner DM. Nerve injuries in the throwing elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23:723-742, xi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Treihaft MM. Neurologic injuries in baseball players. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:187-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cain EL, Dugas JR, Wolf RS, Andrews JR. Elbow injuries in throwing athletes: a current concepts review. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:621-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Spinner RJ. Nerve Entrapment Syndromes. Its Disord. 4th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier 2009; 1090-1118. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Aoki M, Kanaya K, Aiki H, Wada T, Yamashita T, Ogiwara N. Cubital tunnel syndrome in adolescent baseball players: a report of six cases with 3- to 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jobe FW, Stark H, Lombardo SJ. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:1158-1163. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gee AO, Angeline ME, Dines JS, Altchek DW. Ulnar nerve issues in throwing athletes. Ulnar Collat. Ligament Inj. A Guid. to Diagnosis Treat. New York: Springer 2015; 179-188. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Hayton M, Talwalkar S. Nerve entrapment around the elbow. In: Stanley D, Trail I, editors. 1st edition. Elsevier 2012; 455-473. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Upton AR, McComas AJ. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet. 1973;2:359-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 726] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bencardino JT, Rosenberg ZS. Entrapment neuropathies of the shoulder and elbow in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:465-487, vi-vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Glousman RE. Ulnar nerve problems in the athlete’s elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9:365-377. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Li X, Dines JS, Gorman M, Limpisvasti O, Gambardella R, Yocum L. Anconeus epitrochlearis as a source of medial elbow pain in baseball pitchers. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e1129-e1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Childress HM. Recurrent ulnar-nerve dislocation at the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zemel NP. Ulnar neuropathy with and without elbow instability. Hand Clin. 2000;16:487-495, x. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:233-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1017] [Cited by in RCA: 955] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aoki M, Takasaki H, Muraki T, Uchiyama E, Murakami G, Yamashita T. Strain on the ulnar nerve at the elbow and wrist during throwing motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2508-2514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wright TW, Glowczewskie F, Cowin D, Wheeler DL. Ulnar nerve excursion and strain at the elbow and wrist associated with upper extremity motion. J Hand Surg Am. 2001;26:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Spinner RJ, Goldner RD. Snapping of the medial head of the triceps and recurrent dislocation of the ulnar nerve. Anatomical and dynamic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:239-247. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Del Pizzo W, Jobe FW, Norwood L. Ulnar nerve entrapment syndrome in baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 1977;5:182-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Conway JE, Jobe FW, Glousman RE, Pink M. Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes. Treatment by repair or reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:67-83. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Rettig AC, Ebben JR. Anterior subcutaneous transfer of the ulnar nerve in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:836-839; discussion 839-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Andrews JR, Timmerman LA. Outcome of elbow surgery in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Azar FM, Andrews JR, Wilk KE, Groh D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Petty DH, Andrews JR, Fleisig GS, Cain EL. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in high school baseball players: clinical results and injury risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1158-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thompson WH, Jobe FW, Yocum LA, Pink MM. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in athletes: muscle-splitting approach without transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Koh JL, Schafer MF, Keuter G, Hsu JE. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in elite throwing athletes. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1187-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Paletta GA, Wright RW. The modified docking procedure for elbow ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: 2-year follow-up in elite throwers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1594-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rohrbough JT, Altchek DW, Hyman J, Williams RJ, Botts JD. Medial collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow using the docking technique. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:541-548. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Tan V, Pope J, Daluiski A, Capo JT, Weiland AJ. The V-sling: a modified medial intermuscular septal sling for anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:325-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |