Peer-review started: January 2, 2015

First decision: January 20, 2015

Revised: June 28, 2015

Accepted: July 21, 2015

Article in press: July 23, 2015

Published online: January 18, 2016

Processing time: 378 Days and 8.8 Hours

Sacral fractures following posterior lumbosacral fusion are an uncommon complication. Only a few case series and case reports have been published so far. This article presents a case of totally displaced sacral fracture following posterior L4-S1 fusion in a 65-year-old patient with a 15-year history of corticosteroid use who underwent open reduction and internal fixation using iliac screws. The patient was followed for 2 years. A thorough review of the literature was conducted using the Medline database between 1994 and 2014. Immediately after the revision surgery, the patient’s pain in the buttock and left leg resolved significantly. The patient was followed for 2 years. The weakness in the left lower extremity improved gradually from 3/5 to 5/5. In conclusion, the incidence of postoperative sacral fractures could have been underestimated, because most of these fractures are not visible on a plain radiograph. Computed tomography has been proved to be able to detect most such fractures and should probably be performed routinely when patients complain of renewed buttock pain within 3 mo after lumbosacral fusion. The majority of the patients responded well to conservative treatments, and extending the fusion construct to the iliac wings using iliac screws may be needed when there is concurrent fracture displacement, sagittal imbalance, neurologic symptoms, or painful nonunion.

Core tip: Sacral fractures following posterior lumbosacral fusion are rare. This article presents a case of totally displaced sacral fracture following posterior L4-S1 fusion. Computed tomography has been proved to be able to detect most such fractures and should probably be performed routinely when patients complain of renewed buttock pain within 3 mo after lumbosacral fusion. The majority of the patients responded well to conservative treatments, and extending the fusion construct to the iliac wings using iliac screws may be needed when there is concurrent fracture displacement, sagittal imbalance, neurologic symptoms, or painful nonunion.

- Citation: Wang Y, Liu XY, Li CD, Yi XD, Yu ZR. Surgical treatment of sacral fractures following lumbosacral arthrodesis: Case report and literature review. World J Orthop 2016; 7(1): 69-73

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i1/69.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i1.69

Sacral fractures following posterior lumbosacral fusion are an uncommon complication, previously described in only a few case series and case reports. Although these sacral fractures are rarely reported, their incidence could be much higher than previously thought. One of the reasons for underdiagnosis of these fractures is that they are usually unrecognized on plain radiographs, and establishment of a diagnosis is often dependent on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Another reason is that many of these fractures can heal without intervention in a few months, which makes them difficult to be noticed by doctors.

Risk factors for developing sacral fractures following lumbosacral fusions have been identified by several authors. They include old age, female sex, obesity, smoking, postmenopausal osteoporosis, chronic corticosteroid use, prior radiation therapy, graft harvesting, multisegmental lumbosacral fusion, and abnormal spinopelvic alignment. According to the reported experience, most of these fractures occurred within 3 mo after surgery, and the majority of these patients responded well to conservative therapy. Surgical intervention may be needed when there are persistent neurological deficits, significant displacements, severe pain, or fracture nonunion.

This article presents a case of totally displaced sacral fracture following posterior L4-S1 fusion in a 65-year-old patient with a 15-year history of corticosteroid use who underwent open reduction and internal fixation using iliac screws.

The current case was a 65-year-old overweight female (body mass index = 25.63 kg/m2) who presented with a chief complaint of 5 years of progressively increased left lower extremity pain and difficulty in walking, which were refractory to conservative management. The patient was ambulant with 4/5 lower extremity weakness. Both Hoffmann’s sign and Babinski’s sign were negative. The patient suffered from asthma and had a 15-year history of corticosteroid use. A bone density test of the hip (T-score to -3.7) showed poor bone quality.

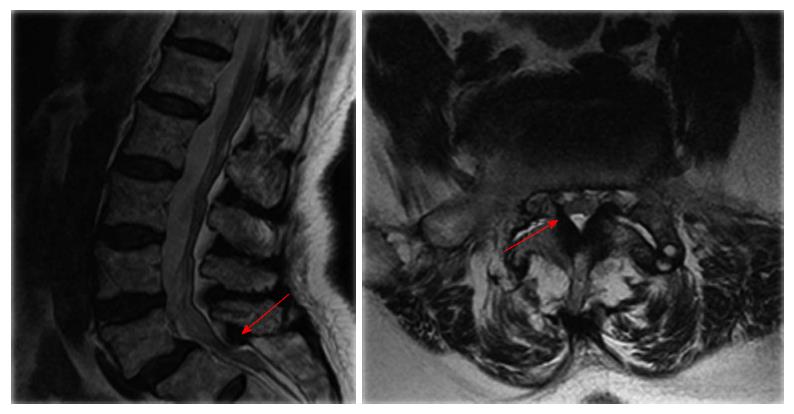

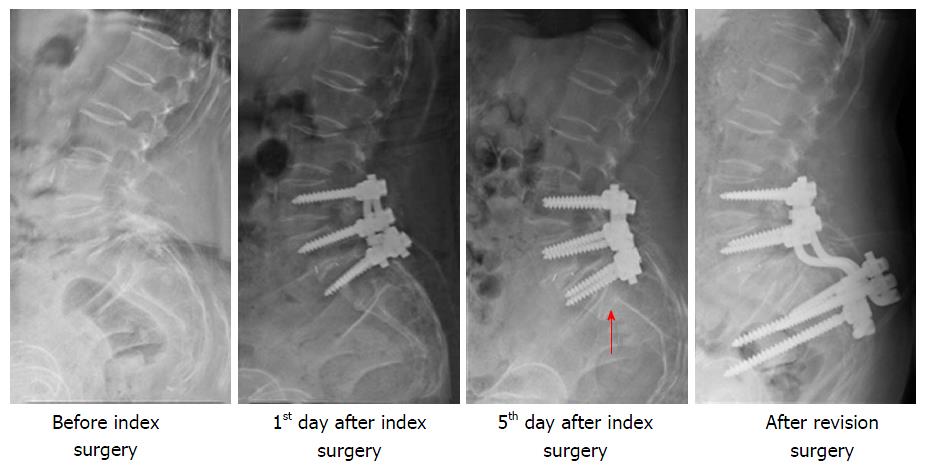

Roentgenograms revealed grade 2 anterolisthesis of L5 on S1. The MRI of the spine found central lumbar spinal stenosis at the L5/S1 level and L4-S1 foraminal narrowing (Figure 1). L4-S1 posterior fusion with poly-axial pedicle screws and double rods (XIA II, Stryker) was performed with posterolateral bone grafting using an autologous lamina/spinous process. A cage was also inserted into the L5/S1 disc.

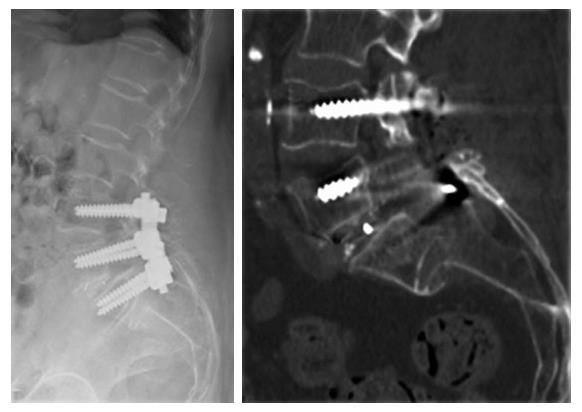

The patient tolerated the procedure well and was walking well on the first postoperative day. On the 5th day after surgery, however, the patient reported a sudden exacerbation of bilateral buttock pain, left-leg radicular pain and sphincter disturbances without precedent trauma. Physical examination revealed a 3/5 weakness of the left lower extremity. A CT scan revealed a horizontal fracture at the S1/S2 level with S2 being totally displaced (Figure 2).

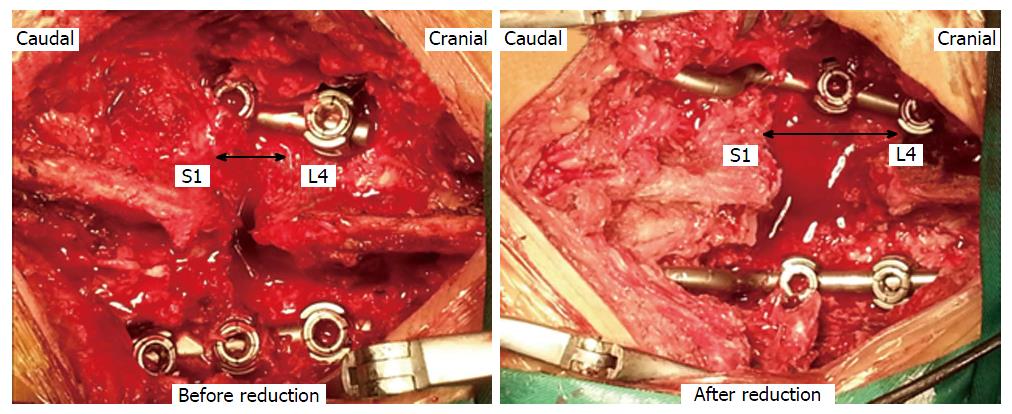

We tried to reduce the fracture with traction but failed. Considering the significant neurological deficits and severe S2 displacement, we performed posterior neural decompression and hardware revision with deformity reduction for the patient at 2 wk after the index operation. The fusion construct was extended to the iliac wings using iliac screws (Figures 3 and 4).

Immediately after the revision surgery, the patient’s pain in the buttock and left leg resolved significantly. The patient was followed for 2 years. The weakness of the left lower extremity improved gradually from 3/5 to 5/5.

The sagittal radiographic parameters are listed in Table 1. The preoperative values indicate that she had a high PI (64.1°) and SS (37.1°).

| Pelvic incidence | Sacral slope | Pelvic tilt | Lumbar lordosis | |

| Before index surgery | 64.1° | 37.1° | 27° | 53.9° |

| After index surgery | N/A | 36.7° | N/A | 51.3° |

| After revision surgery | N/A | 30.3° | N/A | 47.4° |

| 2 yr | N/A | 31.4° | N/A | 45.9° |

Sacral fractures following posterior lumbosacral fusion are rarely seen, and there has been a paucity of data on the association in the published literature. Before 2013, only 34 cases had been reported. No cohort with more than 5 cases had been published until recently. Many spine surgeons have never encountered or noticed such a type of fracture.

The incidence of postoperative sacral fractures could have been rather underestimated. Because most of these fractures are not visible on a plain radiograph, diagnosis is mostly established based on CT, MRI, or nuclear scintigraphy. There are 2 studies with a larger cohort that have been published recently. Meredith et al[1] included all patients undergoing posterior lumbosacral arthrodesis at their institution between 2002 and 2011. Twenty-four out of 392 (6.1%) patients presented with sacral fractures after surgery, which were confirmed by CT, MRI, or nuclear scintigraphy. However, in only one out of the 24 cases, could the sacral fracture be noticed on the postoperative radiographs. Wilde et al[2] reported a cohort of 23 patients who had sacral fractures after lumbosacral fusion. Similarly, the sacral fracture was noticed in only one out of 23 patients on the postoperative radiographs. As such, sacral fractures after lumbosacral fusion could have been greatly underdiagnosed. CT has proven to be able to detect most of such fractures and should probably be performed routinely when patients complain of renewed buttock pain within 3 mo after lumbosacral fusion.

Old age, female sex, osteoporosis, obesity, and a long moment arm of multisegmental lumbosacral fusion are the most frequently cited risk factors for sacral fractures after posterior lumbosacral fusion. The current case had a 15-year history of corticosteroid use for her asthma. The bone density test of the hip (T-score to -3.7) showed a poor bone quality. Furthermore, abnormal spinopelvic alignment could also be a risk factor for fracture development.

To prevent the onset of postoperative sacral fractures, fixation of the iliac wings can be considered in high-risk patients.

The reported experience showed us that these postoperative sacral fractures responded well to conservative treatments, which included activity modification, external immobilization, and medical treatment of osteoporosis[3-5]. However, sacral insufficiency fractures with significant displacement, sagittal imbalance, neurologic symptoms, or painful nonunion may necessitate surgical stabilization. The most commonly performed procedure is to extend the fusion construct to the iliac wings using iliac screws. Fracture union and pain relief were achieved in all the surgically treated cases reported in the literature[1-8].

In conclusion, the incidence of postoperative sacral fractures could have been rather underestimated, because most of these fractures are not visible on a plain radiograph. CT has been proved to be able to detect most of such fractures and should probably be performed routinely when patients complain of renewed buttock pain within 3 mo after lumbosacral fusion. The majority of the patients responded well to conservative treatments, and extending the fusion construct to the iliac wings using iliac screws may be needed when there is concurrent fracture displacement, sagittal imbalance, neurologic symptoms, or painful nonunion.

A 65-year-old patient with a 15-year history of corticosteroid use reported a sudden exacerbation of bilateral buttock pain, left-leg radicular pain and sphincter disturbances without precedent trauma on the 5th day after posterior L4-S1 fusion.

Physical examination revealed a 3/5 weakness of left lower extremity.

Osteoporotic vertebral compressive fracture, epidural hematoma, malposition of pedicle screws, and migration of pedicle screws.

A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a horizontal fracture at the S1/S2 level with S2 being totally displaced.

The authors performed posterior neural decompression and hardware revision with deformity reduction for the patient at 2 wk after the index operation. The fusion construct was extended to the iliac wings using iliac screws.

Sacral fractures following posterior lumbosacral fusion are rarely seen, there has been a paucity of data on the association of this condition in the published literature. Before 2013, there were only 34 cases that had been reported. No cohort with more than 5 cases had been published until recently.

Sacral fractures following posterior lumbosacral fusion are an uncommon complication. Risk factors include old age, female sex, obesity, smoking, postmenopausal osteoporosis, chronic corticosteroid use, prior radiation therapy, graft harvesting, multisegmental lumbosacral fusion, and abnormal spinopelvic alignment.

The incidence of postoperative sacral fractures could have been rather underestimated, because most of these fractures are not visible on plain radiograph. CT has been proved to be able to detect most of such fractures and should probably be performed routinely when patients complain of renewed buttock pain within 3 mo after lumbosacral fusion. The majority of the patients responded well to conservative treatments, and extending the fusion construct to the iliac wings using iliac screws may be needed when there is concurrent fracture displacement, sagittal imbalance, neurologic symptoms, or painful nonunion.

It’s a well-organised study.

P- Reviewer: Emara K, Erkan S

S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Meredith DS, Taher F, Cammisa FP, Girardi FP. Incidence, diagnosis, and management of sacral fractures following multilevel spinal arthrodesis. Spine J. 2013;13:1464-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wilde GE, Miller TT, Schneider R, Girardi FP. Sacral fractures after lumbosacral fusion: a characteristic fracture pattern. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:184-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mathews V, McCance SE, O’Leary PF. Early fracture of the sacrum or pelvis: an unusual complication after multilevel instrumented lumbosacral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:E571-E575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fourney DR, Prabhu SS, Cohen ZR, Gokaslan ZL, Rhines LD. Early sacral stress fracture after reduction of spondylolisthesis and lumbosacral fixation: case report. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1507-1510; discussion 1510-1511. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Elias WJ, Shaffrey ME, Whitehill R. Sacral stress fracture following lumbosacral arthrodesis. Case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:135. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Wood KB, Schendel MJ, Ogilvie JW, Braun J, Major MC, Malcom JR. Effect of sacral and iliac instrumentation on strains in the pelvis. A biomechanical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:1185-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gotis-Graham I, McGuigan L, Diamond T, Portek I, Quinn R, Sturgess A, Tulloch R. Sacral insufficiency fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:882-886. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Odate S, Shikata J, Kimura H, Soeda T. Sacral fracture after instrumented lumbosacral fusion: analysis of risk factors from spinopelvic parameters. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:E223-E229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |