INDICATIONS AND CHALLENGES

Several authors have recommended using the DAA in patients of nearly all body habitus and hip conditions[4,7]. The ideal patient has been described as a flexible, non-muscular patient with valgus femoral neck and good femoral offset. It is reasonable to initially develop skills to perform the approach in slender patients with a body mass index of less than thirty[8]. As achievement of appropriate exposure is gained with experience using the technique, it has also been suggested that lack of appropriate instrumentation designed for anterior supine intramuscular approach is a contraindication[8]. Some anatomic features of the native hip and pelvis are recognized to make the DAA more difficult. A wide or horizontal iliac wing limits access to the femoral canal for broaching and femoral component placement. Acetabular protrusio brings the femoral canal closer to pelvis and obstructs access to femur. A neck shaft angle with decreased offset positions the femoral canal deeper in the thigh, and anatomy associated with obese muscular males limits the space available to place components[9]. One disadvantage of the anterior approach is diminished access to the posterior column. If the patient has a deficient posterior acetabular wall from previous hardware or trauma, or if posterior acetabular augmentation is contemplated, the anterior exposure may be unsuitable[10].

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Patient positioning

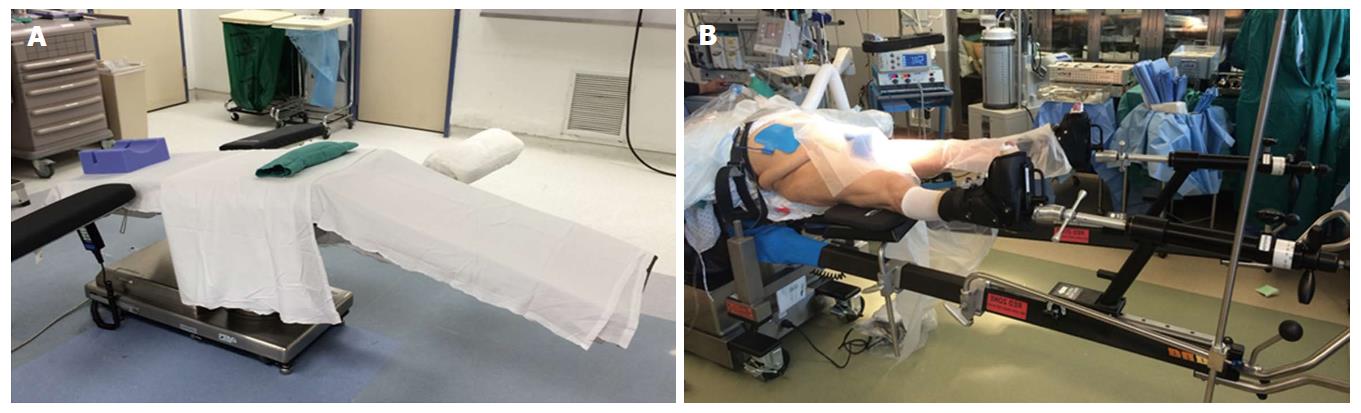

The vast majority of authors describing the DAA position the patient supine on a fracture or regular table. Michel et al[11] also proposed performing anterior total hip arthroplasty (THA) using lateral decubitus positioning. When using a regular table, the patient is positioned with the pelvis located over the table break, which can be angled to allow hyperextension at the hip joint (Figure 1A). A bump may be used placed under the sacrum, centered at the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to further elevate the pelvis[3]. Kennon et al[12] recommends orienting the table at right angles to the walls for accurate referencing and anatomic orientation. The contralateral leg is frequently draped into the field, and an arm board may be placed alongside to allow for abduction during femoral exposure[8]. Obese patients should have the pannus retracted with adhesive tape to avoid interference with exposure[7]. With use a fracture table (Figure 1B), the peroneal post should be well-padded to avoid peroneal nerve neuropraxia[13].

Figure 1 Patient positioning.

A: Use of a regular table with bump under the sacrum and ability to lower the distal end of the bed down to afford better femoral exposure. An extra arm board can be placed on the contralateral distal end of the bed to support the contralateral leg while accessing the operative femoral canal; B: Patient positioning on a fracture-type table (Hana table, Mizuho Orthopedics Systems, Inc.).

Surgical approach

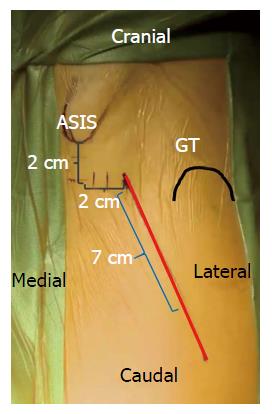

The descriptions for skin incision vary by surgeon, however most authors rely on the ASIS and greater trochanter as anatomic landmarks for reference (Figure 2). An oblique incision is made originating 2-4 cm distal and lateral to the ASIS to a point a few finger breaths anterior to the greater trochanter[4,7,8,11,14,15]. A cadaveric anatomy study showed that the zone immediately distal to the intertrochanteric line formed an anatomic barrier to protect neurovascular structures. Incision extension distal to this point risks damage to branches of the lateral femoral circumflex artery (LFCA) supplying the proximal quadriceps muscles and femoral nerve divisions to the vastus intermedius and lateralis[16]. The incision is generally oriented in line with the TFL, which can also be delineated by a line from the ASIS to the patella or fibular head, or in line with the femoral neck[17]. Fluoroscopy may be used to assist in identifying the femoral neck and midpoint for the incision[18].

Figure 2 Surface anatomy for the direct anterior approach.

A 6-8 cm oblique incision is typically used by the authors. This incision may be extended proximally and distally as needed along the Smith-Petersen interval for adequate femoral and acetabular exposure.

A well-recognized complication of this approach is the proximity of the incision to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN). Though it is commonly believed that remaining lateral to the TFL/sartorius interval reduces risk for injury to the nerve, a cadaveric study of LFCN arborization showed the gluteal branch crossed the anterior margin of the TFL at 44 mm from the ASIS; the femoral branch also crossed this margin in half of specimens, at an average of 46 mm distal to the ASIS[19,20]. A 10% variation in branches was found in a study of 60 cadavers[21]. De Geest et al[22] found a decreased incidence of LFCN injury by further lateralizing their incision. Blunt dissection through the subcutaneous fat is recommended to further minimize risk of nerve injury[7]. Damage to the medial subcutaneous fat pad should be avoided to prevent injury to the trunk of the LFCN, which can result in meralgia paresthetica[8].

The interval between the TFL and sartorius is entered by incising the fascia over the medial TFL muscle belly, retaining an adequate sleeve of tissue for closure and offering protection to the LFCN[4,15,23]. Care should be taken to ensure the appropriate interval, as dissection through the lateral TFL and not in the intramuscular portal may result in damage to the motor branch of the superior gluteal nerve[7]. If the exposure is too posterior, blood vessels will be seen entering the fascia and the fascia becomes denser as it overlies the gluteus medius, which should prompt recognition of the improper interval[15]. Conversely, if the plane is developed too medially, dissection in to the femoral triangle will occur, risking injury to the femoral neurovascular bundle[19]. Blunt dissection separates the TFL muscle belly from the fascia and facilitates entry into the interval for proper exposure of the hip capsule.

Hip exposure

A sharp retractor may be placed around the greater trochanter and the rectus femoris can be retracted medially with a rake or Hibbs retractor[8]. The ascending branches of the LFCA usually lie in the distal portion of the approach, though can be somewhat variable in location and extent; these vessels should now be visualized and ligated with electrocautery or hand suture tie. Some surgeons have employed bipolar sealing technology for the purposes of vessel coagulation and hemostasis throughout the procedure. The instrumentation is replaced with a curved retractor over the superior capsule to retract the TFL superiorly. A second cobra or Hohmann can be placed in a “soft spot” proximal to the vastus lateralis, on the medial of the neck to retract the rectus femoris and sartorius medially. Overzealous retraction should be avoided to minimize damage to the TFL and rectus, as well as to avoid neurovascular traction.

Specialized retractors with extra-depth blades and curved sides (Figure 3) are also available for minimally invasive surgery to facilitate gentle soft tissue handling[19]. In muscular patients, the rectus femoris and TFL insertions near the ASIS may be elevated to facilitate exposure[7]. A capsulotomy or capsulectomy of the anterior capsule have both been described. Some authors advocate removal of the capsule to facilitate exposure. However, retaining a medial portion may provide a sleeve of tissue between the iliopsoas tendon and acetabular rim to reduce irritation[13,24,25]. Kennon et al[12] advised removal of a thick, contracted anterior capsule to prevent impingement possibly contributing to posterior dislocation. Positioning the operative leg in a figure-four position on a regular table can assist in release of the anterolateral and inferior capsule in the calcar region[15,23]. Release of the superior capsule has been shown in a cadaveric study to be the most crucial in allowing elevation of the femur, which was not increased with release of the posterior capsule[26]. Following capsular release, attention is then turned to the femoral neck and head.

Figure 3 Selected retractors used for direct anterior approach.

From left to right, hip skid for ceramic head reduction, greater trochanteric retractor/elevator, femoral elevator for medial/calcar exposure (front and side views), medial acetabular wall retractor, posterior acetabular wall retractor, and tensor fascia lata retractor.

The visible labrum and anterior osteophytes may be excised to assist in removal of the femoral head, but this is often not necessary. Medial and lateral retractors are repositioned within the capsule around the femoral neck. The head may be removed by performing a femoral neck cut and placing a corkscrew in the head, or by first excising a “napkin ring” section of the neck. Placement of a hip skid along the anterior acetabulum with a slightly distracted femoral head, via traction to the limb or instrumentation in the head, can facilitate head removal and transection of the ligamentum teres[13,27]. Gentle external rotation can help with dislocation. If not already done so, the femoral neck cut based on pre-operative planning is performed, with completion of the cut near the greater trochanter finished using an osteotome to reduce the risk of fracture by an oscillating saw.

Acetabulum

A sharp retractor may be inserted at the ventral acetabular rim, keeping the retractor immediately adjacent to the bone to avoid femoral nerve compression[19]. Some surgeons use a light-mounted retractor in this position to improve visualization. Additional retractors are frequently placed at the posterior acetabulum and at the level of the transverse acetabular ligament. Remaining labrum and obstructing osteophytes are removed from the acetabulum, and reaming is commenced. Most surgeons performing this approach advocate use of specialized offset instruments. However, a straight reamer can be used with adequate exposure and careful attention to avoid leverage of the anterior acetabulum to prevent eccentric anterior reaming. Post et al[3] also recommend positioning the reamer head first and then attaching the handle for challenging access. If performing the procedure in the lateral decubitus position, visualization of the anterior acetabulum is difficult and can complicate reaming and cup placement.

Assessing the native pelvis to assist proper cup positioning may be accomplished by palpating the anterior superior iliac spines[19]. Although there is a tendency towards over-anteverting the cup with this approach by holding the cup positioner too vertical, an advantage of the supine DAA is the ability to utilize fluoroscopy intra-operatively[19]. Many surgeons recommend reaming and cup placement using image guidance, particularly in initial adoption of the technique. A press-fit acetabular cup may be inserted with a target abduction angle of 35-45 degrees and anteversion of 10-20 degrees.

Of note, a study of fluoroscopy-guided anterior hip arthroplasty found an early higher rate of dislocation using a goal of 10-30 degrees of anteversion, which was improved by adjusting the target angle to 5-25 degrees[28]. Computer aided navigation has also been described to improve accuracy of cup placement. A study of computed tomography-based hip navigation comparing mini-anterior and mini-posterior found an accuracy of 2.0 degrees for abduction and 2.7 degrees for anteversion of cup placement with the anterior approach. Surface registration took one minute longer in the anterior approach but operative time was not significantly different[29]. A review of 300 DAA hips, half performed with computer aided navigation, showed decreased operative times with navigation and greater accuracy of abduction angles[30]. Following placement of the cup, an acetabular liner is inserted and acetabular retractors are removed.

Femur

The femur may be exposed on a fracture table by dropping the limb spar to the floor, with all traction removed, by a non-scrubbed assistant, along with external rotation and adduction of the limb. Adequate soft tissue capsular releases about the proximal femur should be performed prior to this maneuver. Matta et al[27] utilized a scrubbed assistant to provide additional external rotation force at the femoral condyles using to reduce the stresses generated by the traction boots across the ankle, which can subject patients to iatrogenic ankle fracture. A retractor should be located at the calcar region, and a second retractor at the lateral greater trochanter during this maneuver. Release of the posterosuperior capsule will aid in clearance of the greater trochanter from behind the acetabular rim[8].

Using a regular table, this exposure is performed by dropping the distal end of the table and by placing the bed in a Trendelenburg position, forming an inverted V-shape of the body for hyperextension at the hip. Trendelenburg positioning may alternatively be established at the onset of the case; however, patients undergoing general anesthesia may be at higher risk for gastrointestinal reflux[13]. The contralateral leg may be placed on a mounted arm board or padded Mayo stand to allow for adduction of the operative limb under the contralateral leg in a figure-of-four position on a regular table[24]. For lateral decubitus positioning, the operative limb is abducted, hyperextended, externally rotated and flexed at the knee, with the foot positioned into a sterile bag posterior to the patient.

Elevation of the femur may be accomplished using a hydraulic lift hook or manual placement of a hook just distal to the vastus ridge around the posterior femur. Tension on the femur can be appreciated through tactile and visual feedback of the retractor behind the greater trochanter. In cases where the femur is unable to be appreciably exposed using these maneuvers, Moskal et al[9] described sequential releases of soft tissue along the medial greater trochanter and femoral neck under tension, progressing through the release of hip capsule, piriformis, gemelli, and obturator internus. Posterior circumflex vessels should be identified and cauterized with these releases[12]. The obturator externus provides hip stability through the most medial pull of the femur to the pelvis and should not be released unless necessary[9]. Adequate entry to the femur should be verified with removal of interfering bone or tissue by rongeur or box cutter to prevent varus stem positioning[13]. A high-speed burr may also be used as necessary.

Offset hand instruments may be preferred for broaching and stem placement. An alternative method to providing access utilizes a separate stab wound proximally in line with the femoral canal. This technique may be useful in large or muscular patients and for revision arthroplasty, and can prevent the need for extensive posterior releases[12]. As femoral perforations are a known early complication of this approach, Post et al[3] recommended identifying the trajectory of the canal through use of a guide wire on a T-handle. The femur is then broached and the trial component inserted. Reduction of the hip is performed by reversal of the steps utilized in exposing the femur. Fluoroscopy can be used to assess the adequacy of components, and a stability assessment is performed, emphasizing careful attention to extremes of external rotation and extension. Leg lengths may be compared directly on a regular table or by utilizing radiographic comparison to the contralateral limb with a fracture table[13-15]. Final components are then placed in a similar fashion, and a final stability examination is performed.

Closure

The wound is thoroughly irrigated, and closure is performed according to surgeon preference. If capsulotomy was made, the flaps may be approximated. Hematoma prevention requires adequate hemostasis, as there is higher predilection for hematoma formation with less inherent gravity pressure over an anterior wound compared to other approaches. Furthermore, the risk for hematoma to track deeply exists as the only layer routinely closed is the tensor sheath[31]. Suturing of the tensor fascia latae should be performed with care to avoid damage to the LFCN medially. The subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed in a standard fashion. Many surgeons choose to leave a drain in place beneath the fascial layer; however, a study of 120 patients comparing drain utilization found that patients without drains had an earlier dry surgical site and were discharged from the hospital on average one day earlier. There was a non-significant trend toward high pain scores on post-operative day one, with increased thigh swelling on post-operative day two. There were no difference in transfusion requirements between the groups[32].