INTRODUCTION

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for knee arthroplasty was initially introduced to the orthopaedic community in the early 1990s and was designed for unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA)[1,2]. The surgical approach was novel at that time and was met with a great deal of skepticism. Since the UKA prostheses only replaced one compartment of the knee joint, they were less bulky than the total knee prostheses and were potentially easier to implant. During that period of time, there was some skepticism about UKAs so the procedure and approach did not gain very much support. Just after 2000, orthopaedic surgeons began to look at the UKA results more critically and investigated using the approach for total knee arthroplasty (TKA)[3,4]. Several different surgical approaches were attempted that required varying levels of skill[5-8]. The MIS results included a faster recovery with less blood loss, greater range of knee motion, and less perioperative pain. However, there were multiple reports of complications and revisions[9,10]. The initial enthusiasm quieted and the approaches were all revisited with greater care and more attention to patient selection.

Many surgeons felt that the accelerated recovery and associated benefits of the MIS procedures were not entirely attributable to the surgical technique alone. They felt that improvements in the physical therapy, pain management, and anesthetic techniques were also significant contributors to the change in the result. While the surgical approaches were being refined, there many associated changes that were incorporated into the surgery that would be termed “MIS”. The anesthetic techniques were modified to include spinal, epidural, peripheral nerve blocks, and intraarticular injections[11]. The pain medications were modified to avoid agents that inhibited a rapid recovery and had unacceptable associated side effects, such as nausea and vomiting[12-14]. This led to the introduction of a perioperative multimodal approach to pain management. The length of stay in the hospital was shortened in attempt to encourage a more rapid recovery with less complications[15].

The ultimate aim of all of these changes in the surgical experience was to improve patient satisfaction with the operation. This led to a more thorough investigation of the ultimate result with more consideration of the patient’s view. New evaluation scores were designed leading to a more thorough evaluation of the final result from several different aspects[16-19].

Thus, the surgery, pain management, hospitalization, and rehabilitation were all modified with the introduction of the MIS procedures. The patient’s perception of the result became much more important and the postoperative evaluation changed[20-22].

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

UKA and TKA were both developed in the early 1970s[23,24]. Exposure for the surgery was critical and the designers emphasized visualization. The early results of UKA were similar to the results of TKA but there was a good deal of controversy between the two designing camps. Marmor and Galante continued to develop the UKA and modify the prostheses to improve the results. Insall et al[25] reported high failure rates with UKA and discouraged many surgeons from pursuing the replacement. Murray introduced the mobile bearing design and supported it with good mid and long term results[26,27]. Despite this increased interest in UKA, TKA continued to be the most popular approach through the 1980s and 1990s.

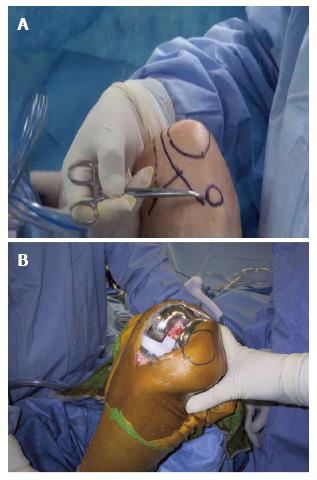

In 1992 Repicci et al[1] implanted UKAs through a modified surgical approach that incorporated an abbreviated skin incision and arthrotomy. He encouraged the patients to ambulate immediately after the surgery and discharged most of the patients within 24 h of the operation. The incision was 10 cm in length and the median parapatellar arthrotomy extended from the superior pole of the patella just down to the tibial joint surface (Figure 1). The prosthesis was a fixed bearing design with cement fixation. He used smaller modified instruments from his dental experience that facilitated the operation. The results were exciting and raised the interest of many orthopaedic surgeons around the world. The early reports were quite encouraging but longer term follow up did show some prosthetic loosenings, perhaps related to the tibial inlay surgical technique[2].

Figure 1 The incisions for minimally invasive surgery of the knee.

Popularity of this approach for UKA continued and more reports came out in the literature supporting the technique[28]. The mobile bearing design was becoming more popular in Europe and a limited incision did lend itself to the technique. The overall number of UKAs in the United States during the 1990s was not very high so the technique did not get overwhelming support; however, the knee arthroplasty community was aware of the development and Repicci was invited to present his work to the Knee Society annual meeting in 2001. Total knee arthroplasty surgeons became more interested in the limited surgical approach and began to look into the possibility of implanting the total knee prosthesis.

There are four techniques that utilize a limited approach to total knee arthroplasty: Quadriceps sparing, mini-midvastus, mini-subvastus, and the mini-parapatellar.

QUADRICEPS SPARING TECHNIQUE

In 2002, a technique was developed that implanted a total knee prosthesis through a limited median parapatellar incision that became known as the “quadriceps sparing approach”[3]. The skin incision was 10 cm in length and the arthrotomy extended from the superior pole of the patella to 2 cm below the tibial joint line on the medial side of the knee (Figure 2). The technique required modified instruments that were smaller and designed specifically for the approach[29]. The instruments were unique in design and somewhat unfamiliar to the orthopaedic community (Figure 3). The operation was demanding and required some cadaveric training for most arthroplasty surgeons. The early results were encouraging and the designing surgeons reported a faster recovery, with less blood loss, greater range of motion but somewhat less accuracy for the alignment of the prostheses[5]. During the early period of development there were reports of failures and revisions that were mostly related to technical issues with the compromising surgical technique[9,10]. This was not an operation for all patients or for all surgeons and it became evident that the choice of the patient and the surgical ability of the operating surgeon were both critical to the result.

Figure 2 Anatomic location of the incision.

A: The skin outline of the minimally invasive surgery incision and its relationship to the patella, the medial femoral condyle, and the tibial joint line; B: Total knee arthroplasty with the quadriceps sparing approach.

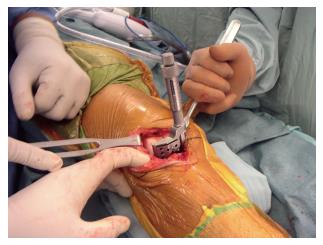

Figure 3 Specially designed instruments for minimally invasive surgery total knee arthroplasty.

This instrument resects the anterior aspect of the femur in full extension.

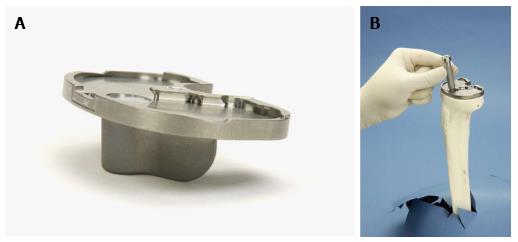

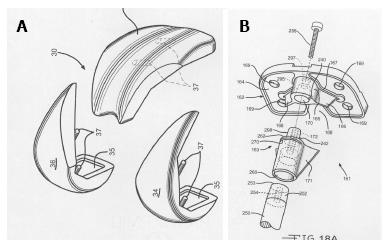

Some companies modified the prostheses to facilitate insertion by limiting the tibial stem length (Figure 4). Modular designs for both the tibia and the femur were considered but never came to implantation (Figure 5).

Figure 4 Implants designed specifically for minimally invasive surgery total knee arthroplasty.

A: A limited keel on a modified tibial tray for MIS; B: A dropdown stem used with a modular tibial tray.

Figure 5 Modular components for minimally invasive surgery total knee arthroplasty.

A: Modular femoral component; B: Modular tibial component.

Surgeons learned to perfect the approach over the ensuing years and the results of the technique improved[29,30]. Modified instruments along with good patient selection and surgical technique have proven valuable[31].

MINI-MIDVASTUS TECHNIQUE

The midvastus approach to the knee was well established before the MIS surgeries were developed[32]. During the period of time when the quadriceps sparing technique became popular, surgeons looked for a modification that might be easier to apply[6,7]. The midvastus approach divides the vastus medialis in the line of its fibers at the junction of the distal one third and the proximal two thirds of the muscle belly (Figure 6). Limiting this division of the vastus medialis to 2 cm in length and carrying it distal along the medial side of the patella to the tibial joint line produced an approach that was familiar to surgeons and compatible with MIS surgery. This was also an extensile exposure that could be modified if the visualization became too limited. However, extension proximally into the vastus medialis muscle fibers may lead to potential denervation of the distal one third of the muscle and may disrupt the associated vasculature with hematoma formation.

Figure 6 Mini-midvastus arthrotomy.

The dotted line shows the medial arthrotomy with the continuation of the incision into the vastus medialis muscle splitting the distal one third of the muscle from the proximal two thirds in the line of the fibers.

The mini-midvastus has become the most popular approach for MIS surgery. It does not require major instrument modification and does permit extension of the arthrotomy to accommodate the more difficult cases. The incision into the vastus muscle does not appear to weaken the quadriceps total muscle strength if the division is kept to 2 cm or less.

MINI-SUBVASTUS TECHNIQUE

The subvastus approach to the knee is another technique that was established in the 1990s, well before the MIS era[33]. The approach is based upon the principle that there is no incision into the quadriceps musculature. The entire quadriceps muscle is lifted across the anterior aspect of the femur and retracted laterally. The arthrotomy incision is made along the inferior border of the vastus medialis and taken distally along the medial side of the patella (Figure 7). The incision along the border of the muscle is critical to the exposure. If the incision is extended proximally beneath the muscle, the penetrating vessels may be divided and can lead to a hematoma, and in extreme cases this can lead to a compartment syndrome in the thigh[34,35]. Any addition bleeding in this area can lead to swelling that may inhibit the range of motion exercises after the operation with a possible contracture.

Figure 7 Subvastus arthrotomy.

The subvastus incision along the inferior border of the vastus medialis muscle. The scalpel blade is along the inferior edge of the vastus medialis and will extend the arthrotomy from there distally along the medial side of the patella and the patellar tendon.

The original subvastus approach required an extensive exposure[33,36]. The approach was then modified by to limit the exposure and make it more MIS friendly[8]. The technique was difficult to accomplish and required proper patient selection. Larger, more muscular males presented difficult knees for the technique. Moving the entire quadriceps muscle laterally in these cases required significant retraction and manipulation of the knee. The operation did lead to a faster recovery but was much more demanding of the surgeon and did not maintain its popularity.

MINI-MEDIAL PARAPATELLAR TECHNIQUE

Many surgeons looked towards the MIS operations as desirable in themselves but saw the complications and difficulties and looked for a modification of the standard arthrotomy that might afford similar results with less difficulty. The mini-medial parapatellar arthrotomy used the standard median parapatellar approach and limited the incision to 4 cm into the quadriceps tendon[37]. The technique did allow for a less extensive exposure and the results were similar but not identical to the MIS reports. This technique remains useful and allows the surgeon to judge the exposure throughout the operation with minimal to no limitations. The approach can also be limited to even a greater extent with a 2 cm incision into the quadriceps tendon. This limitation has been compared to the quadriceps sparing technique and found to produce the same clinical result[30].

The mini-medial parapatellar arthrotomy represents a good compromise for the surgeon and the patient. It does allow a truly MIS technique with the 2 cm quadriceps incision but also gives the surgeon some leeway to modify the operation if the exposure starts to limit the operation.

INSTRUMENTATION

The MIS techniques all advocate a more limited exposure to avoid injuring the surrounding soft tissues. The original instruments for replacement were designed without any size limitation. Large instruments do not fit comfortably in a smaller incision and there were reports of malalignment[38]. If the instruments are radically changed, the technique is less familiar to the surgeon and this may also contribute to improper positioning and early failures. Most surgeons advocate modification of existing instruments that will fit in the limited exposure and allow for greater familiarity.

CLINICAL RESULTS OF MIS

The designing surgeons for each technique reported excellent results with short term follow-up. The quadriceps sparing technique was the most difficult surgery and the designers did note that some components were more than 3 degrees from the ideal alignment but this did not lead to clinical failures[5]. The patients did have greater range of motion, less pain, and a faster return to full activities. Other authors compared the technique to the standard one and found no clinical difference with more complications in the quadriceps sparing group[39]. The more recent publications from experienced, non-designing surgeons report less pain, greater range of motion, less blood loss, with a faster overall recovery time than the standard operative technique. They do not report greater complications or greater incidence of malalignment[40].

The mini-midvastus technique results were equal to the standard from the beginning of the reports. Hass and Laskin were able to perfect the technique with minor instrument modifications and modified patient selection[6,7].

The mini-subvastus approach has had mixed reports in the literature. The developers were able to use the original, standard arthrotomy incision with adequate exposure[33]. However, with the introduction of the smaller incision the technique was more difficult and Boerger et al[41] found that the surgical time was greatly increased. Pagnano felt that the technique could be applied to all cases without compromise at all[42]. Most authors advocated the technique for less obese patients with a good range of motion for the involved knee.

The mini medial parapatellar technique is the simplest of the surgeries. The length of the incision into the quadriceps tendon is important and Tanavalee reported improved results that were similar to the quadriceps sparing technique if the quad incision was limited to only 2 cm[30].

PAIN MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES AND REHABILITATION

The MIS techniques forced surgeons to look at the entire TKA approach for patients. Many criticizers felt that the rapid recovery was not just the operation itself but also the associated pain management and rehabilitation changes that occurred at the same time. Pain management included not only the operation but also preemptive medicating before the surgery and postoperative support[11-13]. Opioids came under scrutiny because of the associated nausea and vomiting. Combinations of drugs that included non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and even steroids were added to protocols.

The anesthetic programs changed with greater emphasis on spinal and epidural techniques to avoid the cardiovascular problems associated with general anesthesia[11]. Peripheral nerve blocks became popular and fit well with early hospital discharge. The blocks had to be modified to avoid injury to the injected nerves and also to try to decrease weakening the quadriceps muscle group after the surgery. This weakening led to a longer period of knee immobilizer usage to avoid inadvertent falls in the immediate postoperative period[43,44]. Femoral and sciatic nerve blocks were replaced with adductor nerve blocks in an attempt to avoid the muscle weakening[45].

Local injections in and around the knee joint became popular when it appeared that the technique could give excellent pain relief with no effect upon the quadriceps muscle group[46,47]. This led to many different preparations and follow up studies that compared local injection to nerve blocks showing the two techniques produced similar pain relief. The addition of steroid to the preparation remains controversial but under consideration[48].

The MIS procedures also included rapid rehabilitation protocols. Patients were mobilized on the day of surgery and were encouraged to return home quickly with earlier discharges from the hospitals[49]. In some cases the procedures were also moved to surgical centers where patients could go home on the same day as the surgery or within 23 h of the operation.

The question with all of these modifications was how much of the changes that occurred were related to the MIS surgical technique itself and how much to the associated changes that were made at the same time? The designing surgeons often took credit for the entire bundle of changes and others who were opposed to the new technology belittled the operative technique as difficult and unrelated to the rapid recovery.

ASSOCIATED TECHNOLOGIES

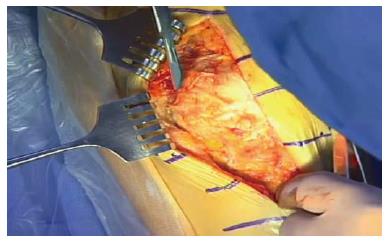

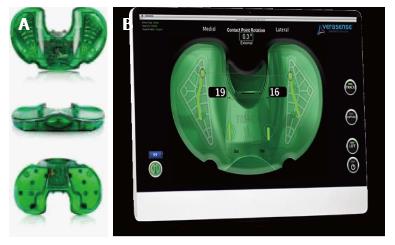

Once the MIS procedures were fully developed designers continued to make changes to improve the surgical techniques and make them more user friendly for the practicing surgeon. The major criticism for the MIS operations was the accuracy of the component positions. Visualization has always been the chief issue with the operations. Navigational support seemed to be a logical addition but less than 5% of surgeons adhered to this technology. Navigation remains an expensive technology that helps the less experienced surgeon but adds cost and time that is prohibitive. When appropriately applied, navigation does make the surgery more accurate but is still a peripheral item. Patient specific instrumentation (PSI) helps to eliminate multiple surgical steps and does have a place in MIS surgery but it is not reliable in all cases, especially with respect to the tibial resection, and adds another expense to the operation (Figure 8). There are new, so-called “smart instruments,” that can be used on a disposable basis to improve implant accuracy. These instruments include dynamic gyros that locate anatomic landmarks in space and guide the cuts (Figure 9). Pressure sensors are also available on a disposable basis that enable the surgeon to evaluate the balance of the knee and improve soft tissue tension (Figure 10).

Figure 8 Cutting blocks for patient specific instrumentation.

A patient specific cutting block for tibial resection.

Figure 9 Smart instruments for alignment of total knee arthroplasty cuts.

Orthalign™ (Orthalign, Aliso Viejo, California, United States) instrument for femoral and tibial resection.

Figure 10 Sensor devices for total knee arthroplasty.

A: Orthosensor™ (Verasense, Orthosensor, Dania Beach, Florida, United States) inserts for the modular trial tibia; B: Pressure recording from the Orthosensor™ plate.

Finally, robotic appliances have also been improved. The haptic instruments are guided by the surgeon’s hand but limit the excursion of the cutting device and the depth of the bone resection. Studies have indicated that these instruments can promote accuracy and decrease outliers especially in a limited surgical incision (Figure 11)[44].

Figure 11 Haptic instrumentation for total knee arthroplasty.

A: Navio™ (Blue Belt Technologies, Plymouth, MN, United States) robotic hand piece that is a haptic control. The surgeon moves the cutting instrument and the computer turns the device off if the resection area is exceeded or the depth is too great; B: MAKOTM (MAKO surgical corporation, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, United States) robotic arm. A haptic arm that is moved by the surgeon within the confines of the resection area and within the proper depth.

CONCLUSION

MIS knee arthroplasty has changed the way we look at TKA. Initially, the smaller incisions did lead to compromises in the clinical results and to skepticism. While surgeons were learning to improve the exposures and perfect the techniques, rehabilitation programs were modified and the patient’s perspective became much more important. Pain management became an integral part of the arthroplasty regimen and comprehensive programs were developed. The MIS techniques have led to easier recoveries, with less pain, less blood loss, greater range of motion, and more satisfied patients.

P- Reviewer: Drosos GI, Gasparini G, Guerado E S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ