Peer-review started: June 21, 2014

First decision: July 10, 2014

Revised: July 23, 2014

Accepted: October 14, 2014

Article in press: October 16, 2014

Published online: January 18, 2015

Processing time: 269 Days and 18.9 Hours

Spinal cord infections were the diseases defined by Hypocrite yet the absence of modern medicine and there was not a real protocol in rehabilitation although there were many aspects in surgical treatment options. The patients whether surgically or conservatively treated had a lot of neurological, motor, and sensory disturbances. Our clinic has quite experience from our previous researchs. Unfortunately, serious spinal cord infections are still present in our region. In these patients the basic rehabilitation approaches during early, pre-operation, post-operation period and in the home environment will provide significant contributions to improve the patients’ sensory and motor skills, develop the balance and proriocaption, increase the independence of patients in daily living activities and minimize the assistance of other people. There is limited information in the literature related with the nature of the rehabilitation programmes to be applied for patients with spinal infections. The aim of this review is to share our clinic experience and summarise the publications about spinal infection rehabilitation. There are very few studies about the rehabilitation of spinal infections. There are still not enough studies about planning and performing rehabilitation programs in these patients. Therefore, a comprehensive rehabilitation programme during the hospitalisation and home periods is emphasised in order to provide optimal management and prevent further disability.

Core tip: Spinal cord infections were not a real protocol in rehabilitation although there were many aspects in surgical treatment options. In these patients the basic rehabilitation approaches during early, pre-operation, post-operation period and in the home environment will provide significant contributions to improve the patients. The aim of this review is to share our clinic experience and summaries the publications about spinal infection rehabilitation. There are very few studies about the rehabilitation of spinal infections. Therefore, a comprehensive rehabilitation programme during the hospitalization and home periods is emphasized in order to provide optimal management and prevent further disability.

- Citation: Nas K, Karakoç M, Aydın A, Öneş K. Rehabilitation in spinal infection diseases. World J Orthop 2015; 6(1): 1-7

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v6/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v6.i1.1

Spinal infections were first noted in the historical record dating back to 4000 Before Christ when Hippocrates described the symptoms of tuberculous spondylitis. Pott’s paraplegia was described by Sir Percivall Pott in the eighteenth century. Infections of the spine and infections of the spinal cord and surrounding structures can directly or indirectly cause damage to the spinal cord with subsequent neurologic compromise[1]. Most common causes in the etiology are osteomyelitis, discitis, tuberculosis of the spine, epidural abscess, arachnoiditis, intramedullary spinal cord abscess, transverse myelitis, spinal cord involvement by the human immunodeficiency virus and other infectious etiologies[2].

Great developments have been achieved in the diagnosis and management of spinal infections. Despite the use of broad spectrum antibiotics and advances in surgical treatment techniques and stabilization methods, spinal infections still keep their importance due to the diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of sequelae[3,4]. Therefore, spinal infections should be included in education programs for all physicians who interested in the management of low back pain, especially in developing countries and even in industrialized countries due to the increased incidence of tuberculosis in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

All patients who admitted with neck and back pain should also be evaluated in terms of spinal infections and rehabilitation, because early diagnosis leads to early treatment and early rehabilitation[5]. Particularly in endemic regions such as undeveloped countries, brucellar and tuberculosis spondylitis should be kept in back pain. An early diagnosis will prevent the development of more severe complications such as spinal cord compression. Delayed diagnosis leads to increased morbidity. As there is almost always a late diagnosis during pharmacological treatment and rehabilitation, there has to start an early rehabilitation in order to diminish mortality and its economic costs. Physical medicine and rehabilitation has a prevailing role in the improvement of the functional prognosis in this disease[6].

Limited information exists in the literature about the nature of a rehabilitation program to be applied for patients treated for spinal infections. Our goal as a rehabilitation concept is to identificate a fast and accurate diagnosis because spinal infection have many signs/symptoms and could be mimicked by various diseases and start to the rehabilitation as possible as early. The goal of rehabilitation is to ensure that the patients can continue his/her daily life and business life independently.

Our clinic has extensive experience and publications about spinal infection rehabilitation. The rehabilitation of patients with spinal infections and our experiences are presented herein. Pediatric spinal cord injury (SCI) patients have not been included in this review; this review is about only adult patients.

Although the treatment varies according to the etiological factors in acute phase plan, combination of antibiotics, drainage (if indicated) and surgical intervention are the main options[2]. Before addressing rehabilitation procedures, we will concentrate on pain and resting that are important in rehabilitation practice. Back pain is the most common clinical manifestation in the patients with spinal infection diseases. Low back pain which related to spinal infections or rehabilitation procedures may have negative influences on the rehabilitation program, so the pain management has critical importance. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesics and muscle relaxants can be initiated as required. In the absence of any contraindications, this treatment can be continued up to 2-4 wk. Narcotic analgesics can be initiated when there is no response to this treatment or for early pain management[7]. One of the aspects of the management of low back pain due to spinal infection is resting. Although resting is not recommended except for an acute period of non-infectious low back pain, it is recommended in spinal infections both for pain management and for the maintenance of stability[8]. The resting period in cases without neurologic deficits should be kept minimal (24-72 h); however, it may be prolonged depending on general status, pain severity, and stability in cases with neurologic deficits. Prolonged immobilization will lead to weakness in the trunk and lower extremity muscles and will contribute to the development of complications. Prolonged immobilization may also induce generation of secondary gains[9,10].

Since spinal infections are generally considered under the heading of non-traumatic spinal cord injuries, it is suggested that the patients should be evaluated as having spinal cord injury. However, the etiologic factors in non-traumatic SCI are tumor, degeneration, infection and vascular etiology, transverse myelitis, spina bifida, syringomyelitis. The differences in the etiological factors of non-traumatic SCI, among different countries, may be due to social, cultural, and genetic differences[11]. The factors such as age, prognosis, the period of illness, the severity of illness, the surgical endicaton and response to treatment effect the rehabilitation (spinal kord eclipse ifadesi bence çıkarılmalıdır). Due to spinal cord infections are different, their rehabilitation are different as well. The infections should be handled differently. When the complications at the times of hospital admissions were assessed, the number of complications in the non-traumatic SCI group was found to be less than the number of complications in the traumatic SCI group. In one study, it has been reported that complications such as spasticity, pressure ulcers, deep venous thrombosis, and autonomic dysreflexia in non-traumatic SCI patients had been found to be less often when compared to traumatic SCI patients[11,12]. These complications are typically observed in cases with severe neurologic damage and instability[13,14].

Non-traumatic spinal cord lesions represent a significant proportion of individuals with spinal cord lesions who admitted in rehabilitation clinics, and it is important to further evaluate their demographic, neurological presentation and functional outcome[15,16]. A plethora of literature is available on the medical complications as well as on the neurological and functional outcome of traumatic spinal cord lesions, but very few studies have focused on medical complications[17,18], etiology[19-21], neurological[22,23] and functional[15,16] outcomes after non-traumatic spinal cord lesions. However, very few studies are present related with neurological and functional rehabilitation in spinal disease infections[7,24,25]. Irrespective of the etiology, severity and extent of insult to the cord, patients with spinal cord lesions perform better in activities of daily living, including self-care, personal toilet, transfer and locomotion by whatever means, in a much better way after rehabilitation intervention and show significant neurologic recover[22,23].

A previous study have reported significant functional recovery in patients with non-traumatic spinal cord lesions after rehabilitation intervention[26].

In studies evaluating the complications in patients of non-traumatic SCI, it was found that urinary tract infection was the most common complication. Pressure ulcers were the second most common complication in the non-traumatic SCI[11,27]. Both the neurological and functional status of non-traumatic SCI patients were better than the patients in the traumatic SCI group[11,26,27,28].

Functional status was better at the time of the hospitalization in the non-traumatic SCI group vs the traumatic group, however functional gain and functional efficiency have been found to be low in the non-traumatic group. In other words, response to rehabilitation therapy has been found to be better in the traumatic SCI group. The prognosis for neurologic recovery is affected mainly by SCI severty and etiology, and is usually more ameliorative in non-traumatic SCI patients than traumatic SCI patients[29]. The little that is known about recovery rates following non-traumatic SCI patients mentioned in a few studies about spinal tuberculosis[28,30-32]. Total recovery rate was 90% in patients with spinal cord tuberculosis following drug therapy and rehabilitation[33].

The clinical status of the patients should be evaluated in addition to the detailed physical examination and system questioning before initiation of the rehabilitation program. Factors; including the general status of the patient, the presence of paresis, the level of the lesion in cases of neurologic involvement, the presence of incontinence, and cardiopulmonary and psychological status should be evaluated in detail. The evaluation of functional status scales is also necessary for optimal rehabilitation programs. It should be taken into consideration that the rehabilitation program requires teamwork and consultation of related clinics with multidisciplinary approach. Brucellosis and tuberculosis are the most frequent chronic infections involving the spine and also our clinical experiences mostly include the rehabilitation of complications caused by these infections in the spine.

Patients with spinal infections are bedridden for certain period, which is longer in those with neurologic deficits or those who were recommended surgical operation. These patients should be monitored closely in terms of complications and treated accordingly. Failure to detect and treat complications, such as hypertension, hypotension, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary infections, urinary retention, urinary infections, spasticity, contractures, decubitus ulcers, depression, and osteoporosis increase morbidity and mortality[34].

Spinal deformity and paraplegia are the significant complications of spinal tuberculosis both of which occur more often in cases of delayed diagnosis and management[35]. Patients with an initial kyphotic angle of 30 degrees or less should be treated with antituberculous medications, with close monitoring for progression of deformity[36]. Rehabilitation programs of patients with neurologic deficits or those who had surgical operation due to spinal infections should be conducted with more care. Complications are observed more frequently and the response to treatment is delayed because of the longer immobilization period.

The most important factor in SCI rehabilitation programme is early rehabilitation. The positioning in the acute phase, early starting of passive, active-assisted and active exercises will greatly contribute standing of the patient earlier and to mobilize. Standing and mobilization are not recommended in the acute period for these patients. Generally, standing and ambulation are recommended during the subacute period. Patients with spinal tuberculous, bracing with a conforming orthosis (plaster or molded thermoplastic) has been used in combination with antituberculous drugs as initial treatment. Bracing is continued 3 mo after the first radiologic sign of bony fusion[37].

The onset of pain or increase in pain during exercise programs in the early period should be evaluated carefully. Pain aggravating exercises should be avoided and the exercise program should be discontinued if there is a significant increase in pain intensity disturbing the patient following the rehabilitation program. The patient should not be exhausted during exercise and mobilization and should have adequate resting after exercise. High calorie diet regimens should be provided since metabolic requirements are increased during both disease and the rehabilitation period.

In general, there are very few studies concerning spinal infection rehabilitation[7,24,25]. Our clinic has significant experiences with these issues. The rehabilitation program is applied with respect to the neurologic status of patient. For this purpose, the levels in which the spinal cord injury may occur and the involved segments are determined before implementation of the program. Following a detailed physical and neurologic assessment, determination of the region that lesion affects the type of paralysis, the urologic and neurologic status, concomitant diseases, the age of patient, and the involved region is crucial to establish a realistic and optimal rehabilitation program. Following this assessment, patients should be monitored closely in terms of maintaining good posture, bed care, and positioning during early rehabilitation. The presence of instability and the type of surgical procedure are important for the implementation of rehabilitation program. Musculoskeletal problems and secondary problems as a result of immobilization should be monitored and prevented[5].

In patients with mild neurologic findings, active or active assistive range of motion and isometric exercises should be applied in all joints of the lower extremity during the acute phase. Accordingly, ambulation of the patient is targeted in the early period. During the subacute period, isotonic exercises for the low back, hip, and lower extremity muscles and mobilization exercises (using corset according to the status of patient as necessary) are performed. Also, balance problems, if exist, are tried to be improved. In the chronic stage, isotonic and strengthening exercises are prescribed for atrophic muscles of patient and mobilization is continued. The patient is discharged by providing a home exercise regimen and followed up at regular intervals[7,24].

In patients with severe neurologic findings due to spinal cord compression, the rehabilitation program differs according to acute, subacute, and chronic stages. In cases with spinal infections, medical treatment should be considered at first, even in cases with spinal cord compression due to paravertebral abscess[38]. However, both surgery and medical treatments are necessary in cases of neurologic involvement.

The most important factor in the acute rehabilitation period is to determine the patient’s physical capacity. According to the degree of infection, the muscles weakness can be seen in varying degrees in lower, upper extremity and trunk muscle. Bed positioning in appropriate with dermatomal areas, passive joint movements and breathing exercises are important in the acute phase of flastisity. Each group of muscles must be evaluated separately if there is muscle weakness. Isometric, passive, active-assisted, active exercises are performed to improve the functional capacity of muscles. This should be done at least daily, which will help to prevent contractures. The shoulder, elbow, hip flexors, and ankles are most important to range, because contractures are most frequently observed in these joints in the acute rehabilitation unit. The most important aspects in the acue period include bowel, bladder, and pulmonary management, deep venous thrombosis, and gastrointestinal prophylaxis and proper positioning in bed with turning at least every 2 h. The trunk and extremities should be properly positioned and the feet should be supported in a neutral position. If the level of spinal infection is in thoracic vertebrae, respiratory exercises are added. The pressure must be reduced in order to prevent decubitus ulcers. While in the supine position, the patient is turned from one side to the other every 2 h to reduce pressure and monitored constantly for erythema formation[4]. An indwelling catheter is placed if urinary incontinence is present.

In the acute stage, isometric exercises are initiated during the pre-operative period and continued during the early post-operative period. The patient is assisted to be mobilized within the bed by turning from one side to the other. Isometric contraction is sustained by isometric compression of the lumbar, thoracic, and sacrospinal muscles towards the bed. Isometric exercises are performed in cervical, thoracic, and sacrospinal muscle groups and all lower extremity muscles; patient in the supine position continues to elevate head and shoulder until the toes are visible. Gluteal muscles are contracted and relaxed bilaterally and isometric contraction of the pelvic muscle group is provided[7,24].

Subacute period is the out of bed ambulation period of the patients. According to the width of the localization of infection and the patient with appropriate assistive devices bodice and on the edge of the bed before backing out of bed by then, with crutches or walker is focused on mobilization. Also bearing exercises quadriceps exercises in addition to the side of the mattress is required to be done in an active way. Standing on the edge of the bed and standing proper ways are taught.

Active and active assisted exercises are performed during the subacute stage. Feet are raised straightly and contraction of hip flexors and lumbar extensors is performed by raising the bilateral quadriceps muscles about 20 cm. The patient is assisted by the corset to sit on the bed (supported or unsupported). Balance exercises are performed at this position. The patient is assisted to walk by cane or walker. Mobilization is repeated up to 3 or 4 times daily. The patient is left to rest after the onset of signs of fatigue. Assistive equipment is withdrawn following the successful independent mobilization of the patient[7]. Clean intermittent catheterization is performed instead of continuous indwelling catheter to prevent urinary infections. The patient should be examined at certain intervals for urinary infection, should drink enough water and should be ambulated continuously. The patient should be fed by high-fiber food to prevent constipation which might be a significant problem. The patient should be taken to the rest room once or twice a day to stimulate defecation[4]. If the upper extremities are preserved, active strengthening exercises should be performed for all upper extremity joints.

The chronic period is a term that the patients return back to his previous life and regain maximum independence. For this purpose, the patients should be awayed from bed. Mobilization should be done independently supported or unsupported. Lying down, sitting and standing exercises should include active and resistive exercise. The balance and gait exercises assets should be studied in parallel bars. Climbing stairs, squat, sit on the ground activities like lifting should be done. The patients are assisted to walk by using crutches or orthotics during the chronic stage. Patients who achieve trunk and pelvic stabilization are taken to the parallel bar by wearing corset for standing exercises. In standing position, forward, backward and sideways stepping exercises, as well as neutral position exercises such as forward flexion, are performed. Cat-camel stretching exercises are performed to strengthen abdominal and dorsal muscles. These exercises may also be performed in bed without wearing corset[7,24].

Decubitus ulcers are significant health problems in patients with paraplegia. Decubitus ulcer should be considered during the chronic stage as well. Depression may occur in patients with spinal cord compression, therefore psychological support should be provided for these patients[4].

Home exercise program based on the patient’s capacity should be designed in such a way that she or he can understand. The home evaluation is an important aspect of the rehabilitation process, to allow the patients to return home. The main areas of concern in the home evaluation include the entrances, bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, and general safety issues. The maximum ergonomic changes should be made as possibly in the patient’s home environment (toilet, bathroom, bedroom, hallway, etc.) in order to ensure the patient’s independancy. Patients’ check-up and general condition should be evaluated at regular intervals. Recommendations should be done specificly to facilitate the patient’s activities of daily living in the late stages where the patients can return back to the work

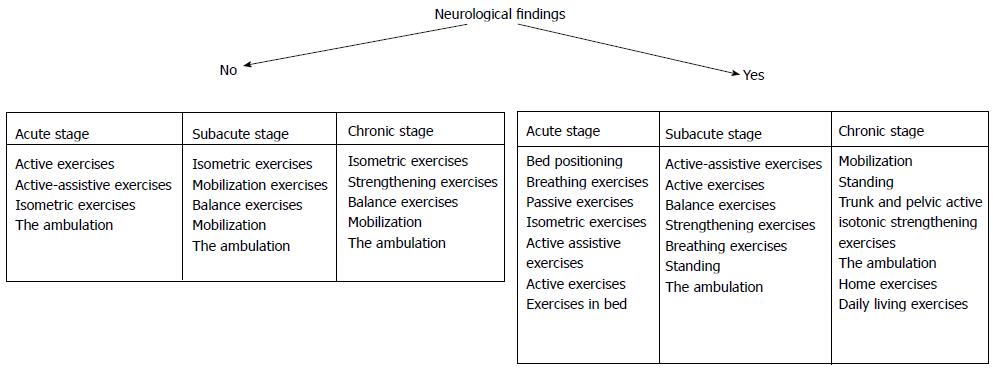

After the completion of the rehabilitation programme in hospital, the patient is then discharged with a home exercise program and followed up at regular intervals. In addition to the exercises performed during the subacute and chronic stages, hand and wrist joint exercises, full abduction, extension and flexion exercises for abdominal, sacrospinal, iliopsoas, gluteus maximus, gluteus minimus, hamstring, and quadriceps muscles, and resistive exercises for oblique abdominal muscles are recommended to be performed at home. Exercises to increase respiratory capacity are continued. Cardiovascular endurance exercises are prescribed after complete improvement of vertebral bones[7]. According to the presence of neurological findings, rehabilitation programme was indicated (Figure 1). A neurologic examination and laboratory tests are performed at the follow-up visits. A multidisciplinary follow-up program is performed together with infectious diseases, pulmonary diseases, neurosurgery, and/or orthopedics clinics when necessary.

We determined significant improvements in discharge scores of the patients with tubercullosis and brucella after their admission to hospital when we evaluated motor scores for lower limbs and modified barthel index (MBI). At the end of the rehabilitation program patients experienced less pain and were able to perform their daily work with fewer complications. In the final radiological examinations of every patient, degenerative alterations at the pathologic disc space were found to be less than we had expected[7,24]. Yen et al[25] evaluated MBI and determined significant improvements in discharge scores of patients with respect to their admission scores. They also found significant improvements in discharge scores of the same patients in terms of the motor scores for the lower limbs.

In general, Cervical spondylodiscitis published reports on the outcome of rehabilitation have been very limited[34,39,40]. Cervical spondylodiscitis is a rare localization of spinal infection, and also may be associated with a higher incidence of devastating neurological complications, and an overall worse prognosis. Thus, the cervical spine was immobilized with a hard neck collor. Neck mobility returned to normal, and the hard neck collar changed to a soft one[34,39]. Neck isometric exercise must start in acute pain stage during that cervical collar was being applied. The cervical corset is applied for immobilization at least for one month due to severity of acut neck pain. Range of motion exercise must start in subacute stage. In the chronic phase, exercise must start to improve the function of the neck muscles, and isotonic was started[38,39].

Whether traumatic or non-traumatic SCI rehabilitation includes quite difficult and a long process for both patients, patients’ relatives and for the rehabilitation team. It is based on multidisciplinary studies as with spinal cord injury. Patients and their relatives are the most important elements of this team. Patient compliance will ensure the success of rehabilitation by simplifying the work of the rehabilitation team. The best rehabilitation target for these patients is to be independent like their past life and be able to rotate without limits. For this purpose the whole medical team must handle the rehabilitation of patients with spinal infection and they should identify the assessment and rehabilitation program as possible as early. The patient should be informed with the idea that success comes with his/her own efforts at the end of a long process.

A successful rehabilitation program should assist patients to return their daily living activities by providing early mobilization with pain reduction, strengthening of weak muscles or prevention of muscle weakening, stabilization, maintenance correct posture and trunk mobilization. Long-term follow up with the spinal cord injury specialist is extremely important. This allow for monitoring of medical issues, reevaluating the therapy program and setting updated goals, and prescribing equipment.

We thank Dr. Volkan ŞAH for his support for review of the manuscript and for insightful comments.

P- Reviewer: Hyun SJ, Lakhdar F, Lin YW S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Us AK. Piyojenik omuga enfeksiyonları (Spina pyogenic infections). Benli T, editor. Omurga enfeksiyonları (Spine infections). Ankara: Rekmay yayıncılık 2006; 351-366. |

| 2. | Garstang SV. Infections of the spine and spinal cord. Kırshblum S, Campagnolo DI, Delisa JA, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2002; 498-512. |

| 3. | Çağlı S. Omurga ve omurga enfeksiyonları (spine and spine infections). Türkiye Klinikleri J surg Med Sci. 2006;2:94-103. |

| 4. | Nas K. Spinal enfeksiyonlar (Spine infections). Göksoy T, editor. Istanbul: Yüce A.Ş 2009; 465-477. |

| 5. | Yılmaz H, Spinal enfeksiyonlarda rehabilitasyon (Rehabilitation of spine infections). In: Spinal enfeksiyonlar (Spine infections). Paloğlu S, editor. İzmir: META Basım 2003; 239-244. |

| 6. | Ribeira T, Veiros I, Nunes R, Martins L. Spondilodyscitis: five years of experience in a department of rehabilitation. Acta Med Port. 2008;21:559-566. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Nas K, Kemaloğlu MS, Cevik R, Ceviz A, Necmioğlu S, Bükte Y, Cosut A, Senyiğit A, Gür A, Saraç AJ. The results of rehabilitation on motor and functional improvement of the spinal tuberculosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:312-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chelsom J, Solberg CO. Vertebral osteomyelitis at a Norwegian university hospital 1987-97: clinical features, laboratory findings and outcome. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:147-151. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Bal A, Gürçay E, Ekşioglu E, Edgüder T, Tuncay R, Çakcı A. Evli birçifte eş zamanlı brucella spondiliti (Brucella spondylits in a married couple). Romatizma. 2003;18:165-170. |

| 10. | Kıtar E. Omurganın brucella enfeksiyonu (Brucella infections of spine). Benli T, editor. Ankara: Rekmay yayıncılık 2006; 531-546. |

| 11. | Ones K, Yilmaz E, Beydogan A, Gultekin O, Caglar N. Comparison of functional results in non-traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1185-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gupta A, Taly AB, Srivastava A, Murali T. Non-traumatic spinal cord lesions: epidemiology, complications, neurological and functional outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM, Osman DR. Osteomiyetis. Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R, editors. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone 2005; 1322-1332. |

| 14. | Nair KP, Taly AB, Maheshwarappa BM, Kumar J, Murali T, Rao S. Nontraumatic spinal cord lesions: a prospective study of medical complications during in-patient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:558-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gupta A, Taly AB, Srivastava A, Vishal S, Murali T. Traumatic vs non-traumatic spinal cord lesions: comparison of neurological and functional outcome after in-patient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:482-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McKinley WO, Huang ME, Tewksbury MA. Neoplastic vs. traumatic spinal cord injury: an inpatient rehabilitation comparison. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Go BK, DeVivo MJ, Rechards JS. The epidemiologic of spinal cord lesion, in: Spinal cord lesion. Stover SL, Delisa JA, Whiteneck GG, eds. Aspen: Gaithersburg 1995; 21-25. |

| 18. | McKinley WO, Seel RT, Gadi RK, Tewksbury MA. Nontraumatic vs. traumatic spinal cord injury: a rehabilitation outcome comparison. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:693-699; quiz 700, 716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Adams RD, Salam-Adams M. Chronic nontraumatic diseases of the spinal cord. Neurol Clin. 1991;9:605-623. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Dawson DM, Potts F. Acute nontraumatic myelopathies. Neurol Clin. 1991;9:585-603. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Schmidt RD, Markovchick V. Nontraumatic spinal cord compression. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:189-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kurtzke JF. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 1975;48:163-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McKinley WO, Tellis AA, Cifu DX, Johnson MA, Kubal WS, Keyser-Marcus L, Musgrove JJ. Rehabilitation outcome of individuals with nontraumatic myelopathy resulting from spinal stenosis. J Spinal Cord Med. 1998;21:131-136. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Nas K, Gür A, Kemaloğlu MS, Geyik MF, Cevik R, Büke Y, Ceviz A, Saraç AJ, Aksu Y. Management of spinal brucellosis and outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:223-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yen HL, Kong KH, Chan W. Infectious disease of the spine: outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | McKinley WO, Seel RT, Hardman JT. Nontraumatic spinal cord injury: incidence, epidemiology, and functional outcome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:619-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | New PW, Rawicki HB, Bailey MJ. Nontraumatic spinal cord injury: demographic characteristics and complications. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:996-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McKinley WO, Tewksbury MA, Godbout CJ. Comparison of medical complications following nontraumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:88-93. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Catz A, Goldin D, Fishel B, Ronen J, Bluvshtein V, Gelernter I. Recovery of neurologic function following nontraumatic spinal cord lesions in Israel. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2278-2282; discussion 2283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Celani MG, Spizzichino L, Ricci S, Zampolini M, Franceschini M. Spinal cord injury in Italy: A multicenter retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:589-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gomibuchi F. [A clinical study on acute non-traumatic myelopathies]. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1988;62:1177-1188. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Parry O, Bhebhe E, Levy LF. Non-traumatic paraplegia [correction of paraplegis] in a Zimbabwean population--a retrospective survey. Cent Afr J Med. 1999;45:114-119. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Jain AK, Kumar S, Tuli SM. Tuberculosis of spine (C1 to D4). Spinal Cord. 1999;37:362-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Raptopoulou A, Karantanas AH, Poumboulidis K, Grollios G, Raptopoulou-Gigi M, Garyfallos A. Brucellar spondylodiscitis: noncontiguous multifocal involvement of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. Clin Imaging. 2006;30:214-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Moon MS, Ha KY, Sun DH, Moon JL, Moon YW, Chung JH. Pott’s Paraplegia--67 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;122-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rajasekaran S, Soundarapandian S. Progression of kyphosis in tuberculosis of the spine treated by anterior arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1314-1323. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Wimmer C, Ogon M, Sterzinger W, Landauer F, Stöckl B. Conservative treatment of tuberculous spondylitis: a long-term follow-up study. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10:417-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nas K, Tasdemir N, Kemaloglu MS, Bukte Y, Gur A, Tasdemir MS. Early response to medical treatment in a case of brucellar spondylodiscitis with medullary compression. J Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabil. 2008;21:201-205. |

| 39. | Nas K, Bükte Y, Ustün C, Cevik R, Geyik MF, Batmaz I. A case of brucellar spondylodiscitis involving the cervical spine. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22:121-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Nas K, Tasdemir N, Cakmak E, Kemaloglu MS, Bukte Y, Geyik MF. Cervical intramedullary granuloma of Brucella: a case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2007;16 Suppl 3:255-259. [PubMed] |