Revised: September 27, 2013

Accepted: October 11, 2013

Published online: January 18, 2014

Processing time: 178 Days and 15.3 Hours

AIM: To examine patients’ perceptions on communication surrounding the cancellation of orthopaedic operations and to identify areas for improvement in communication.

METHODS: A prospective survey was undertaken at a university teaching hospital within the department of Trauma and Orthopaedics. Patients admitted to an acute orthopaedic unit, whose operations were cancelled, were surveyed to assess patient satisfaction and preferences for notification of cancellation of their operations. Patients with an abbreviated mental test score of < 9, patients unable to complete the survey independently, those under 16 years of age, and any patient notified of the cancellation by any of the authors were excluded from this study. Patients were surveyed the morning after their operation had been cancelled thus ensuring that every opportunity was given for the medical staff to discuss the cancellation with the patient. The survey included questions on whether or not patients were notified of the cancellation of their surgery, the qualifications of the person discussing the cancellation, and patient preferences on the process. Satisfaction was assessed via 5-point Likert scale questions.

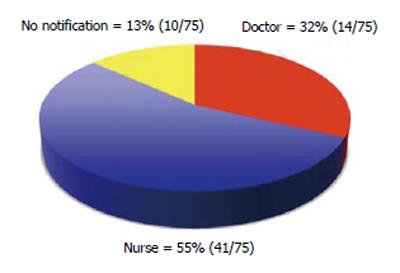

RESULTS: Sixty-five consecutive patients had their operations cancelled on 75 occasions. Fifty-four point seven percent of the patients who had cancellations were notified by a nurse and 32% by a doctor. No formal communication occurred for 13.3% cancellations and no explanation was provided for a further 16%. Patients reported that they were dissatisfied with the explanation provided for 36 of the 75 (48%) cancellations. Of those patients who were dissatisfied, 25 (69.4%) were notified by a nurse. Twenty-three of the 24 (96%) patients notified by a doctor were satisfied with the explanation and that communication. Of those patients who were notified by a nurse 83% patients reported that they would have preferred it if a doctor had discussed the cancellation with them. There was a significant difference in satisfaction between those counselled by a nurse and those notified by a doctor (P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION: Communication surrounding cancellations does not meet patient expectations. Patients prefer to be notified by a doctor, illustrating the importance of communication in the doctor-patient relationship.

Core tip: Communication is a fundamental component of medical practice. This study highlights communication issues surrounding cancellation of orthopaedic operations. It reflects patients’ preferences and expectations in these situations. Failure to meet these preferences and expectations predisposes to dissatisfaction and can negatively impact patient experiences and health outcomes. In the current climate, it may fall to individual practitioners to change their approach to communication and patient interaction. Patients appear to place great value on communication delivered by doctors, and a few extra moments spent conversing with a patient may have profound and lasting effects.

- Citation: Mehta SS, Bryson DJ, Mangwani J, Cutler L. Communication after cancellations in orthopaedics: The patient perspective. World J Orthop 2014; 5(1): 45-50

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v5/i1/45.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v5.i1.45

Communication is a fundamental component of medical practice. Despite widespread introduction of communication skills in medical curricula, and post-graduate courses espousing such skills, poor communication remains a leading cause of patient dissatisfaction and complaints within the National Health Service (NHS)[1]. Operations that are cancelled for non-clinical reasons can cause psychosocial distress, disruption of daily life and have wider socioeconomic implications[2]. The 2002 NHS Modernisation Agency’s Theatre Project, and Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, have published recommendations for dealing with patients whose operation have been cancelled. This includes guidance to reschedule the operation within 28 d[3] and provision of an apology and an explanation for the cancellation by a senior member of the team[4]. Cancellations occur frequently in busy trauma and orthopaedic departments.

To the best of our knowledge there has not been a study examining patients’ perceptions on the communication issues surrounding cancellations in trauma and orthopaedics in the NHS. This prospective study sought to examine current practice in our own department in an attempt to identify areas for improvement in our communication skills and the provision of care.

We created a survey requesting responses on the methods of informing patients of cancellations of their operation in orthopaedic surgery. This study was conducted in a university teaching hospital, in a dedicated trauma unit, that accepts only acute orthopaedic admissions. Since 2005 our hospital has employed specialist-trained nurses as Trauma Coordinators. Working closely with orthopaedic, anaesthetic and theatre teams, the Trauma Coordinators work seven days a week to plan and coordinate theatre lists. This necessarily involves close communication with nursing and medical staff, junior doctors, and patients. Following the morning trauma meeting, attended by the on-call, operating and anaesthetic team, along with the Orthogeriatric consultant and the trauma coordinators, the order of the operative list is determined. Patients are then reviewed by the anaesthetist to assess their fitness for surgery and an anaesthetic plan formulated. If a patient was cancelled at that stage, because underlying medical factors prohibited surgery, then the patient was excluded from this study. Conversely, all patients who potentially remained on the planned trauma list remained eligible for participation in the study. Some patients were kept potentially on the list for either pending medical treatment or blood results for example International Normalised Ratio to be normal or review by Orthogeriatrician.

At our institution, two trauma theatre lists run in parallel each weekday with a single trauma theatre operating over the weekends. One theatre is ring-fenced for hip fracture patients and the other for general trauma. The hip fracture theatre is operational from 09:00-17:00 while the general trauma theatre runs from 09:00 until 20:00. We identified patients who were cancelled from either list. The decision to cancel a patient on the hip fracture list occurred late in the afternoon and cancellations from the trauma list were made in the evening.

All patients who were cancelled were invited to participate in this study. We surveyed patients the morning after their operation had been cancelled. This ensured that every opportunity was given for the medical staff to discuss the cancellation with the patient.

The survey included questions on whether or not patients were notified of the cancellation of their surgery, the qualifications of the person discussing the cancellation, and patient preferences on the process. Satisfaction was assessed via 5-point Likert scale questions. We assessed patients’ satisfaction to overall communication of their entire stay in hospital and not just the episode of cancellation and also overall satisfaction with care provided. This information was collated to assess if communication surrounding cancellation affects these issues as well. A Fisher exact test was used evaluate differences in patient satisfaction and significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

All patients were surveyed after notification of the cancellation and before the re-scheduled operation was performed. The patients were encouraged to reply in their own time without any involvement from any of the staff. Inclusion criteria included any patient whose operation was cancelled for clinical or non-clinical reasons. Examples of the former included cases of blood results or soft tissue swelling which were not normal after the morning review but were kept on the operating list as potential cases pending correction of their issues. Non-clinical reasons mainly incorporated of lack of theatre time. Patients with an abbreviated mental test score of < 9, patients unable to complete the survey independently, those under 16 years of age, and any patient notified of the cancellation by any of the authors were excluded from this study. Those doctors who were involved in the cancellation process did not participate in this study and were not aware that patients were being surveyed. Ethical approval was not required for this study; this was an audit of our current practice against accepted guidelines and it did not involve institution of any form of intervention.

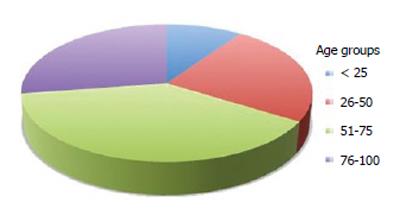

Sixty-five consecutive patients had their operation cancelled on 75 occasions. Individual cause for cancellation was not collated or correlated with satisfaction, as lack of theatre time was the leading cause of cancellations. Thirty-four of those cancelled were male and 31 females. The average age of patients was 59 years (range 17-91) (Figure 1). Ten patients had their operation cancelled on two occasions. A nurse notified patients for 41 (54.7%) of the cancellations and a doctor for 24 (32%) cancellations (Figure 2). Patients reported that they were dissatisfied with the explanation provided for 36 of the 75 (48%) cancellations. Of those patients who were dissatisfied, 25 (69.4%) were notified by a nurse. Overall, there was a significant difference in satisfaction between those counselled by a nurse and those notified by a doctor (P < 0.0001). Twenty-three of the 24 (96%) patients notified by a doctor were satisfied with the explanation and that communication. Thirty-four (83%) patients notified by a nurse reported that they would have preferred it if a doctor had discussed the cancellation with them.

No formal communication occurred for 10 cancellations (13.3%) and no explanation was provided for a further 12 (16%) cancellations. When the results were stratified according to age group (Table 1) it revealed that significant differences between counselling by nurse or doctor were in age group 51-75 years. There was no difference in levels of satisfaction between male and female participants (Table 2). We also looked at 5 point likert scale for overall satisfaction with communication during the stay of the patient in the hospital as oppose to just the cancellation episode. Results revealed that 5 patients were completely satisfied, 30 very satisfied, 19 somewhat satisfied, 17 somewhat dissatisfied and 4 very dissatisfied.

| Age group (yr) | < 25 | 26-50 | 51-75 | 76-100 |

| Satisfied | 3 | 8 | 15 | 8 |

| Not satisfied | 3 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Doctor:Nurse notification | 2:3 (1 NN) | 4:8 (3 NN) | 8:15 (1 NN) | 7:6 (4 NN) |

| P value | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P = 0.0194 | P > 0.05 |

| Fisher Exact Test | Significant |

| Sex | Male | Female |

| Number of patients | 34 | 31 |

| Satisfied | 18 | 17 |

| Not satisfied | 16 | 14 |

| P value | P > 0.05 | |

| Fisher Exact Test | ||

There was significant association between patients who were not informed of their cancellation episode (n = 10) and those that were (n = 65) with their satisfaction with overall communication which was 1:52 respectively (Fisher exact test: two-tailed P value < 0.0001).

A good bedside manner, or the ability to take a medical history, is no longer the benchmark of good communication[5]. Communication skills are a core component of undergraduate and post-graduate medical curricula and communication has evolved into a measurable and assessable clinical skill[5,6]. In spite of this, poor communication remains pervasive-and in some cases can have very grave consequences. The Institute of Medicine in the United States has reported that an estimated 44000 to 98000 Americans die each year because of medical error with poor communication strongly implicated as cause of these errors[7,8]. More commonly, a failure of communication can lead to criticism, complaints and litigation[9-11].

The results of this study suggest that patients have definitive preferences and expectations about the manner in which information is imparted regarding their operations. Members of the nursing team notified patients of their cancellation on 54.7% of cancellations but on the basis of these data patients appear to find this unsatisfactory. Eighty-three percent patients who were notified by a nurse reported that they would have preferred it if a doctor had discussed the cancellation with them. These findings are in keeping with other studies suggesting that physicians are the preferred source of information provision[12,13] and serve to illustrate the importance of the doctor-patient relationship. Of the 34 patients notified by a nurse, nine reported that although they were satisfied with the explanation provided they would have been happier had a doctor discussed the cancellation with them. More worryingly, 10 patients (13% of cancellations) were not informed of their cancellations at all. A lack of theatre time availability was the leading cause for the cancellations. On those occasions when a doctor discussed the cancellation with the patient, 96% were satisfied with the explanation and the communication. Patients who were cancelled for medical reasons in the morning by the anaesthetic team were excluded from participation in this study.

The importance of effective communication and interpersonal skills, and the value ascribed to them by patients, encompasses several domains. According to Simpson et al[14], effective doctor-patient communication represents a central clinical function that cannot be delegated. Good communication can have a positive influence on psychosocial health, functional and physiological status, and pain control[15], with patient satisfaction positively influenced by information provision by doctors[16]. Effective communication can also reduce the incidence of complaints and the incidence of clinical error[17]. In 2011, the Dr Foster Good Hospital Guide reported that disrespect and not being kept informed were two leading reasons why patients would not recommend their hospitals and that they valued this more than same-sex wards or cleanliness[18].

The 2002 NHS Modernisation Agency’s Step Guide to Improving Theatre Performance[3], and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland[4], have acknowledged the psychological impact of cancellations and advised that, in cases of cancellation for clinical reasons and system failings, a senior member of the medical team should visit the patient as soon as possible and offer an apology and explanation for the cancellation. Simpson et al[14] have reported that uncertainty, a lack of information or explanation from doctors is associated with heightened anxiety and dissatisfaction. This was demonstrated in our data where a failure to communicate or provide adequate explanation correlated with overall patient dissatisfaction with communication.

The cause of these shortcomings is multifactorial. In the busy environment of an acute trauma and orthopaedic department it is not always feasible for the operating surgeon or a senior member of the medical team to meet with a patient to break the news immediately that their operation has been cancelled. In our own department, over 3500 trauma procedures are performed each year including more than 800 operations for hip fractures. Any theatre slot vacated by a cancellation may be quickly filled by another patient waiting for surgery. As a consequence, the surgeon will seldom have an opportunity to leave theatre and visit the cancelled patient. It necessarily falls to a member of the nursing team or a ward based junior doctor to perform this role. This deficiency is further compounded by changes instituted as a result of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) and the transition to shift-based rotas. The reduction in working hours to 48 h/wk has reduced the availability of junior doctors and, according to some authors, adversely affected the quality and continuity of patient care in some NHS services[19]. If the cancellation occurs outside normal working hours, the only doctor available to break the news may have no prior knowledge of the history and details for the cancelled patient.

Cancellations occur for a variety of reasons. Many of the factors that conspire to precipitate a cancellation will be outside the control and influence of the orthopaedic surgeon. It is a cause of concern that patients are cancelled because of a lack of theatre time. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the issues of communication irrespective of the reason for cancellation and not to examine the underlying factors for this lack of time. It can be challenging to identify those specific factors that conspire to precipitate the cancellation, but issues such as over-enthusiastic booking, delays in patient transfer, anaesthetics or surgical delays because of challenging patients or cases are regularly implicated. Despite the multifactorial nature of the cancellation, the cause is often attributed to lack of time. While this is invariably the case, citing a lack of time is not entirely reflective of the underlying reason.

This study suggests that one area in which surgeons can exert a positive influence is in the communication of cancellations. Communication skills are an integral component of medical education but this teaching is of little value if these skills are not employed in daily practice. The EWTD, a target-driven NHS, surgical departments operating at, or beyond, capacity may be regarded as barriers to communication. Irrespective of the cause, current practice does not appear to meet patient expectations or preferences and cultural and professional changes may be required to reverse this trend and improve performance.

We recognise that this study has limitations, including the fact that our questionnaire has not been validated. However, as no preceding study has examined this specific area of communication, there is no validated outcome measure available. Secondly, this study took place in a busy trauma unit and may not necessarily reflect the opportunities for communication seen in the elective realm. Lastly, the numbers involved in this study are comparatively small. However, we feel that the issues raised by this project will be applicable and transferable across all surgical disciplines.

The results of this study reveal that patients expect to be notified of cancellations and would prefer to be notified by a doctor rather than a member of the nursing team. While it is not always possible for a senior doctor to break the news of the cancellation, a failure to notify the patient, either by a member of the medical or nursing team, is inexcusable. Moreover, it would not seem unreasonable for a doctor to spend a few minutes with a cancelled patient, even after notification by a nurse, to provide an explanation and address questions or concerns that were not answered or allayed at the initial notification. These findings illustrate the importance of the doctor-patient communication and the value that patients place on this relationship. In the current working environment there may be little scope or latitude for instituting widespread didactic changes in policy and practice. If changes are to be made, they may have to occur at the individual level-it must fall to members of the medical team to change their own practice. This may incur a few additional minutes of work but the impact of a few words of encouragement or a gentle hand of reassurance can have profound and lasting effects.

Communication is a fundamental component of medical practice. Poor communication predisposes to patient dissatisfaction. Good communication is of particular significance when breaking bad news, including notifying a patient of a cancelled operation. They wished to determine patient expectations and preferences regarding communication with a view to identify shortcomings in practice and improve provision of care.

Research has focused on the delivery and execution of communication skills in undergraduate curricula and post-graduate courses. In the area of communication research hotspot is to examine patients’ preferences and expectations on day-to-day provision of care.

This study has identified areas of weakness in communication in a busy orthopaedic trauma unit. Research has shown that good communication can positively influence patient experience and outcomes. To the best of person knowledge no previous study has examined the impact of communication on the notification of cancellation of operation in orthopaedics.

These findings illustrate the importance of the doctor-patient communication and the value that patients place on this relationship. While it is not always possible for a senior doctor to break the news of the cancellation, a failure to notify the patient, either by a member of the medical or nursing team, is inexcusable. Moreover, it would not seem unreasonable for a doctor to spend a few minutes with a cancelled patient, even after notification by a nurse, to provide an explanation and address questions or concerns that were not answered or allayed at the initial notification. Furthermore, this study has highlighted shortcomings in practice, which may be transferred across other surgical disciplines. If changes are to be made, they may have to occur at the individual level. This may incur a few additional minutes of work but the impact of a few words of encouragement or a gentle hand of reassurance can have profound and lasting effects.

Communication- in context of this paper, this term relates to exchange of views between healthcare professional and patient and effectively imparting the information to the patient in a manner that they understand it in context of this paper. Cancellation- in context of this paper, this term stands for cancellation of operation of the patient.

This is an interesting manuscript about doctor-patient communication. The doctor-patient’s relationship is core problem in the medicine surrounding. The goal of this paper was to examine the patients’ perceptions on the communications surrounding cancellation of operations in orthopaedics and to identify areas for improvement in our communication skills. This prospective study was a new method to explore patients’ satisfaction and preferences for notification of cancellation of their operations, by doctor and nurse respectively. The rationale is well presented and the manuscript is clearly written.

P- Reviewers: Eric Y, Guo XO, Kasai Y S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Pincock S. Poor communication lies at heart of NHS complaints, says ombudsman. BMJ. 2004;328:10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schofield WN, Rubin GL, Piza M, Lai YY, Sindhusake D, Fearnside MR, Klineberg PL. Cancellation of operations on the day of intended surgery at a major Australian referral hospital. Med J Aust. 2005;182:612-615. [PubMed] |

| 3. | NHS Modernisation Agency. Theatre Programme. Step Guide to Improving Operating Theatre Performance. . |

| 4. | The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Theatre Efficiency: safety, quality of care and optimal use of resources 2003. Available from: http: //www.aagbi.org/publications/guidelines/theatre-efficiency. |

| 5. | Makoul G. MSJAMA. Communication skills education in medical school and beyond. JAMA. 2003;289:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | von Fragstein M, Silverman J, Cushing A, Quilligan S, Salisbury H, Wiskin C; UK Council for Clinical Communication Skills Teaching in Undergraduate Medical Education. UK consensus statement on the content of communication curricula in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2008;42:1100-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79:186-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nagpal K, Vats A, Lamb B, Ashrafian H, Sevdalis N, Vincent C, Moorthy K. Information transfer and communication in surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2010;252:225-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rodriguez HP, Rodday AM, Marshall RE, Nelson KL, Rogers WH, Safran DG. Relation of patients’ experiences with individual physicians to malpractice risk. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:5-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hargie O, Dickson D, Boohan M, Hughes K. A survey of communication skills training in UK schools of medicine: present practices and prospective proposals. Med Educ. 1998;32:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice. Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1365-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2618-2624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 992] [Cited by in RCA: 942] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Johnson JD, Meischke H. Cancer information: women’s source and content preferences. J Health Care Mark. 1991;11:37-44. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Simpson M, Buckman R, Stewart M, Maguire P, Lipkin M, Novack D, Till J. Doctor-patient communication: the Toronto consensus statement. BMJ. 1991;303:1385-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in RCA: 486] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423-1433. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Pract. 1998;15:480-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Centre for change and innovation, Scottish Executive Health Department. Talking matters: developing the communications skills of doctors. 2003. Available from: http: //www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2003. |

| 18. | Dr Foster Hospital Guide. Inside Your Hospital. 2010–2011. Available from: http: //drfosterintelligence.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Hospital_Guide_2011.pdf. |

| 19. | Cairns H, Hendry B, Leather A, Moxham J. Outcomes of the European Working Time Directive. BMJ. 2008;337:a942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |