Published online Oct 18, 2013. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v4.i4.303

Revised: July 11, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: October 18, 2013

Processing time: 108 Days and 5.7 Hours

AIM: To present the 18 year survival and the clinical and radiological outcomes of the Müller straight stem, cemented, total hip arthroplasty (THA).

METHODS: Between 1989 and 2007, 176 primary total hip arthroplasties in 164 consecutive patients were performed in our institution by the senior author. All patients received a Müller cemented straight stem and a cemented polyethylene liner. The mean age of the patients was 62 years (45-78). The diagnosis was primary osteoarthritis in 151 hips, dysplasia of the hip in 12 and subcapital fracture of the femur in 13. Following discharge, serial follow-up consisted of clinical evaluation based on the Harris Hip Score and radiological assessment. The survival of the prosthesis using revision for any reason as an end-point was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

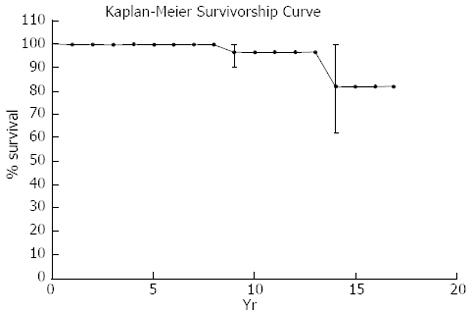

RESULTS: Twenty-four (15%) patients died during the follow-up study, 6 (4%) patients were lost, while the remaining 134 patients (141 hips) were followed-up for a mean of 10 years (3-18 years). HSS score at the latest follow-up revealed that 84 hips (59.5%) had excellent results, 30 (22.2%) good, 11 (7.8%) fair and 9 (6.3%) poor. There were 3 acetabular revisions due to aseptic loosening. Six (4.2%) stems were diagnosed as having radiographic definitive loosening; however, only 1 was revised. 30% of the surviving stems showed no radiological changes of radiolucency, while 70% showed some changes. Survival of the prosthesis for any reason was 96% at 10 years and 81% at 18 years.

CONCLUSION: The 18 year survival of the Müller straight stem, cemented THA is comparable to those of other successful cemented systems.

Core tip: There are few cemented implants that have made history and are still used today. The original Müller straight stem prosthesis falls into this category. In this study, 176 primary cemented total hip replacements in 164 consecutive patients were followed-up for a mean of 10 years (3-18) years. Survival of the prosthesis, as calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis, was 96% at 10 years and 81% at 18 years. The 18 year survivorship of the Müller straight stem, cemented total hip arthroplasty is comparable with that of other successful cemented or uncemented systems.

- Citation: Nikolaou VS, Korres D, Lallos S, Mavrogenis A, Lazarettos I, Sourlas I, Efstathopoulos N. Cemented Müller straight stem total hip replacement: 18 year survival, clinical and radiological outcomes. World J Orthop 2013; 4(4): 303-308

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v4/i4/303.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v4.i4.303

There are few implants that have made history and are still used today. The original Müller straight stem prosthesis falls into this category. The original Müller straight stem prosthesis has shown excellent results at 10 to 15 years[1-4]. The 10 year survival rate for the stem ranges from 91.2% to 98.3%[3,5]. Good results after 10 years of using a third generation cementing technique, with a survival rate of 93.2%, are also presented in the Swedish National Hip Arthroplasty Register[6].

The original forged Müller cemented straight stem (Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland), manufactured from Protasul-10 (CoCrNiMo alloy) with a matte, fine-blasted surface, was introduced in 1977. Müller[7] developed a cemented stem based on the principle of achieving fixation in the bowed femur by inserting the largest possible stem. So for a particular femur, a press-fit is achieved between the medial and lateral walls of the femur and the prosthesis and this leads to an incomplete cement mantle with bone-metal contact. The fluted structure of the stem, with the two particularly marked longitudinal grooves anteroposterior in the stem axis, enables very good cement adhesion. The small proximal collar serves to compress the cement, prevents the stem from sinking into the cement and, together with the fine-blasted surface of the straight stem, achieves a very stable anchorage of the implant. The design of the stem achieves optimum adaptation because it increases rigidity, decreases stress peaks and supports less micromotion. Moreover, there is positive contact in the frontal plane and additional interlocking is often achieved in the sagittal plane by the curvature of the femur.

Long term survival data are only available from Scandinavian hip registries[3,4,6] which lack detail on the clinical or radiological outcome. The aim of this study is to present the 18 year survival, clinical and radiological outcomes of the Müller straight stem, cemented total hip arthroplasty (THA) in our institution. This was a retrospective study of prospectively collected data.

Between July 1989 and June 2007, a total of 176 Müller straight stem primary THAs were performed in our hospital. The mean age of the patients was 62 years (45 to 78). There were 136 women and 28 men. The primary diagnosis was osteoarthritis in 151 patients, dysplasia of the hip in 12 and subcapital fracture in 13 patients.

All operations were undertaken by one single surgeon (N.E.). The patients were operated on in a standardized way, in a supine position through an anterolateral transgluteal approach (Watson Jones). After reaming the acetabulum, the corresponding size polyethylene cup was cemented with the finger-packing technique. The femoral canal was prepared with rasps and the femoral component was introduced with a cement gun. In contrast to other canal-filling implants, no spongious bone was removed in the sagittal plane. All stems were cemented with a second-generation cementing technique. During the first ten years of the study, Palacos bone cement was used, while Gentafix (Teknimed SAS) was used later on in the study. The size of the femoral stem for all patients was 7.5. In all patients, a 28 mm diameter, cobalt-chromium femoral head and a drain that was removed on the second postoperative day was used. All patients received prophylactic antibiosis and anticoagulation therapy. The patients were mobilized after the second postoperative day and full weight bearing was permitted as tolerated.

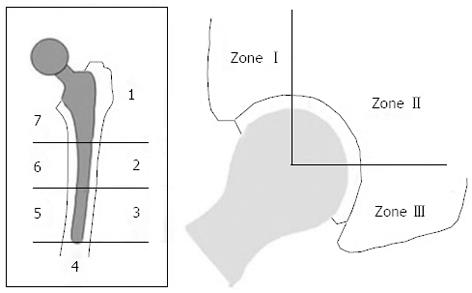

Clinical and radiological follow-up was at 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo and thereafter every year. Clinical follow-up included a standardized examination using the Harris Hip Score (HHS)[8]. At the latest follow-up, a postoperative score of 90-100 points was considered an excellent result; 80-89 points as good; 70-79 as fair; and less than 70 points as poor. Radiological assessment was based on a standardized anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis centered on the pubic symphysis, showing the entire prosthesis, and a second radiograph with the false profile view. The films were rated according to the Gruen zone system for the femoral component and according to De Lee and Charnley for the acetabular component (Figure 1)[9]. Loosening was defined as follows: potential loosening: radiolucency (linear/focal) < 2 mm; probable loosening: linear radiolucency > 2 mm; focal radiolucency > 5 mm; definitive loosening: linear radiolucency > 2 mm all around[1,9] (Table 1). Subsidence of the stem was measured as the difference between the highest point of the prosthesis shoulder and the horizontal sclerotic line above the shoulder.

| Potential loosening | radiolucency (linear-focal) < 2 mm |

| Probable loosening | linear radiolucenc > 2 mm or |

| focal radiolucency > 5 mm | |

| Definitive loosening | linear radiolucency > 2 mm all around |

The indication for revision was persistent patient, pain and/or radiological evidence indicating loosening of the acetabular or femoral component. The 18 year cumulative survival was calculated by a Kaplan-Meier analysis.

This study is conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review board approval has been obtained.

From the 164 patients (176 hips), 24 patients (15%) died, while 6 patients (4%) were lost to follow-up, both without revision at their last review. That left us with 134 patients (141 hips) that they were followed up for a mean of 10 years (range 3-18 years). No patient died during the early postoperative period. In 5 patients (3.5% of hips), the greater trochanter was fractured during the intraoperative manipulations. In all cases, osteosynthesis of the greater trochanter was done by wiring and the patients were kept in bed for prolonged time. This fracture rate can be attributed to the manipulations that are necessary during the anterolateral transgluteal approach (Watson Jones) as the patient lies supine on the OR table (figure of four leg position). Early hip dislocation occurred in 3 patients. Closed reduction under general anesthesia and C-arm control was successfully done and these patients were kept in bed for three weeks with no further complications. No cases of deep infection or pulmonary embolism were noted. Superficial wound infection occurred in 3 patients. In 3 patients, revision of the acetabular component was done 9, 11 and 13 years postoperatively respectively, due to aseptic loosening (Figure 2). One femoral stem was revised due to aseptic loosening.

The mean HHS was 87 (34 to 100), of which 84 (59.5%) of the hips showed excellent (90 to 100 points), 30 (22.2%) good (80 to 89 points), 11 (7.8%) fair (70 to 79 points) and 9 (6.3%) poor results (< 70 points) at the latest follow-up.

All radiographs were evaluated by an experienced hip arthroplasty surgeon. A total of 99 (70%) of all 141 hips had linear or focal osteolysis in one or more zones of the stem but only 6 hips (4.2%) of the 134 analyzed patients had evidence of definitive loosening, while 30 (21%) had no radiographic changes. However, from the 6 (4.2%) hips with radiographic aseptic loosening, only 1 stem was revised because the radiographic findings were not always combined with hip pain (in 2 patients), while the other 2 patients refused to be operated on. Radiographic changes were noticed mainly on the proximal-medial side of the stem (Gruen zones 7 and 6) and rarely laterally (Gruen zones 1 to 3). We found radiolucency of any type in 104 hips (73%). According to the above mentioned definition of loosening: 65 hips (46%) were potentially loose; 33 hips (23.4%) were probably loose; and 6 hips (4.2%) were definitely loose (Table 2)[9]. Stem subsidence was present in 21 hips (15%). 1 mm in 17 stems, 2mm in 3 and 3mm in one stem. We could not identify any correlation between the stem subsidence and the clinical results of these patients.

| Type of radiolucency | No. of hips |

| Overall | 104 (73) |

| Linear-focal < 2 mm | 65 (46) |

| Linear > 2 mm or focal > 5 mm | 33 (23.4) |

| Linear > 2 mm all around | 6 (4.2) |

With revision for any reason, survival was 96% for 10 years and 81% for 18 years (Figure 3).

The limited survival data published for the Müller straight stem shows great variation in outcome: at six to eight years, 20.1% of the stems were judged to be at risk for later aseptic loosening[10] in a series for which further follow-up has not been presented. For stems implanted with a first-generation cementing technique[11], a ten year revision rate of 8% and a revision rate of 19.7% at 17 years was observed, whereas when using a second generation cementing technique[11], the revision rate was reduced to 4% at ten years[6].

The Müller straight stem was designed to achieve a press fit fixation in the anteroposterior radiological view with a self-centering effect (shape-closed). A close stem-bone contact is established in the coronal plane, resulting in a thin or even incomplete cement mantle[1,12,13] which has been described in the literature as the “French paradox”[13]. It is well known that it is desirable to have a complete cement mantle around the stem[14]. The optimum thickness of the cement mantle is thought to be 2-4 mm. However, this conventional teaching has been challenged by the success of French-designed cemented stems, such as the Charnley Kerboull and the Ceraver Osteal. In France, the philosophy had been to insert the largest stem possible, which fully occupies the medullary canal, resulting in a thin or even deficient mantle. The rectangular cross-section provides intrinsic stability in torsion even in the absence of cement[15]. This is the concept for the Muller straight stem. Moreover, the stem design and implantation technique make gross errors in varus-valgus orientation almost impossible as the prosthesis almost fills the femoral canal in the AP plane.

The stem had a satin surface finish (Ra 1.0 μm), exceeding a postulated roughness of 0.4 μm defined as maximum roughness for polished stems. Thus, abrasive wear of the surface and a high volume of metal debris might be expected[16]. Later versions of the stem had an even higher surface roughness and survival decreased[17]. The combination of the soft metal titanium with a rough surface had the worst results[18]. Polished stems have a better survival with force-closed cementing technique (shape-closed implants)[19-21]. However, the biological effect of the abrasive wear of the rough stem might be equally important[21]. This cannot be overcome by modifications to the cementing technique[16] and can only be overcome by polishing the stem.

The Swedish Hip Registry[6] showed improved long term survival for the Müller straight stem using a second-generation cementing technique compared with a series with a first-generation cementing technique. There are no data for third-generation techniques (jet lavage, vacuum-mixed cement) and it must be questioned whether these techniques can further improve the cement penetration for an implant with high introduction forces. The use of ceramic heads was associated with a decreased wear rate and the use of modern bearing surfaces might further improve survival[10,12,13]. The use of a femoral seal or finger-packing might improve the proximal sealing and reduce access of polyethylene particles at the interface, thus reducing the risk of osteolysis for the Müller straight stem.

In the present study, the femoral component was divided into 7 zones, as described by Gruen et al[9]. The development of radiolucent lines around these zones in a progressive fashion suggests loosening. We distinguish progressive radiolucent lines in the femur from the typical age-related expansion of the femoral canal and cortical thinning, which may give the appearance of a progressively widening radiolucency. Age-related radiolucent zones generally do not have the associated sclerotic line seen about loose femoral stems. In addition, radiolucent lines associated with osteolysis tend to be more irregular, with variable areas of cortical thinning and ectasia. Smith et al[22] described an age-related expansion of the human proximal femur in a series of 2300 healthy female femora and postulated that endosteal resorption would result in an expansion of the medullary canal, which might even occur after insertion of a THA[23]. A time and gender-related widening of the medullary canal with consecutive thinning of the cortex has also been reported in female cadaver femora of various ages[24]. Radiologically, an obvious loss of mineralization of the cortex and cancellous bone has been observed in older women[25].

Räber et al[1] reported a 15 year survival rate for aseptic loosening of 88.1% with the Müller straight stem when using a first generation cementing technique, but found that about 70% of the remaining stems exhibited osteolysis or longitudinal lucencies. The incidence of osteolysis was not reported but the longitudinal lucencies might have been due to cortical atrophy. In our series, the incidence of any radiological lucency lines was frequent. A total of 99 (70%) of all 141 hips had radiological changes of lucency, but only 6 hips (4%) had evidence of definitive loosening, while 30 (21%) had no radiographic changes. The high rate of radiolucency without definitive loosening may be explained by the fact that the incomplete cement mantle leaves places with a thin cement mantle and zones with direct metal-bone contact and this allows the particles access to the bone, leading to bone resorption. Consciousness of the natural process of cortical atrophy is necessary in order not to overestimate the number of cases at risk, as cortical atrophy did not compromise the clinical and radiological results. Clauss et al[26] stated that cortical atrophy appears to be an effect of ageing and not a sign of loosening of the femoral component.

Krismer et al[10] found an increased rate for aseptic loosening for Müller straight stems with an incomplete cement mantle at the tip of the stem. In our series, cement defects at the tip of the stem were uncommon (5 hips) and not associated with an increased incidence of revision.

With aseptic loosening as the endpoint, the survivorship according to Kaplan-Meier of the Müller straight stem at 10 and 18 years was 96% and 81% respectively. This survival rate and clinical results are comparable to that of other well known and successful cemented systems in larger multi-surgeon series[4,6].

Total hip replacement is one of the most common surgical procedures. Cementless prostheses, although the most expensive, have become the most common type of prosthesis used for total hip replacement worldwide. However, long term follow-up studies have failed to prove the superiority of cementless hip arthroplasties over the well time-tested cemented designs. There are few implants that have made history and are still used today. The original Müller straight stem prosthesis falls into this category. A long term follow-up of patients with primary total hip replacements that were treated with the cemented Müller straight stem prosthesis is presented in this study.

A long term follow-up of patients with primary total hip replacements that were treated with the cemented Müller straight stem prosthesis is presented in this study. Currently, there is a relative paucity of evidence regarding the survivorship of patients with primary total hip arthroplasties treated with this cemented prosthesis.

This study confirms that cemented Müller straight stem total hip arthroplasty displayed satisfactory survivorship in a long term follow-up. These results are comparable with that reported in other larger series of cemented and uncemented prostheses. The authors should note that the majority of components were implanted using second generation cementing techniques. The polyethylene cup was cemented with the finger-packing technique and the femoral stem was implanted without distal cement plug and without pressurization.

Surgeons should consider using this cemented total hip arthroplasty, taking in to account that uncemented total hip replacements are much more expensive and that the findings of this study and other similar studies confirm that results of cemented hip arthroplasties are at least as good as those reported in uncemented designs.

Total hip replacement can be done using bone cement to stabilize the acetabular and femoral components. This kind of total hip replacement is known as cemented. Alternatively, porous coated materials can be used and the bonding of the implants with the patient’s host bone occurs without the usage of bone cement. This kind of hip arthroplasty is known as cementless.

The paper shows a good follow-up of their patients and leaves few comments to be added.

P- Reviewers Fenichel I, Papadimitriou NG, Schoffl V S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Wang CH

| 1. | Räber DA, Czaja S, Morscher EW. Fifteen-year results of the Müller CoCrNiMo straight stem. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ramiah RD, Ashmore AM, Whitley E, Bannister GC. Ten-year life expectancy after primary total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1299-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Riede U, Lüem M, Ilchmann T, Eucker M, Ochsner PE. The M.E Müller straight stem prosthesis: 15 year follow-up. Survivorship and clinical results. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mäkelä K, Eskelinen A, Pulkkinen P, Paavolainen P, Remes V. Cemented total hip replacement for primary osteoarthritis in patients aged 55 years or older: results of the 12 most common cemented implants followed for 25 years in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1562-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brémant JJ. 10 years follow-up of the M.E. Müller self-locking cemented total hip prosthesis. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1995;81:380-388. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Malchau H, Herberts P, Eisler T, Garellick G, Söderman P. The Swedish Total Hip Replacement Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A Suppl 2:2-20. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Müller ME. Total hip prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;72:46-68. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737-755. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;17-27. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Krismer M, Klar M, Klestil T, Frischhut B. Aseptic loosening of straight- and curved-stem Müller femoral prostheses. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:190-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Breusch S, Malchau H. Optimal cementing technique - the evidence: What is modern cementing technique? BSaM The well cemented total hip arthroplasty: In theory and practice. Heidelberg: Springer 2005; 146-149. |

| 12. | Wilson-MacDonald J, Morscher E. Comparison between straight- and curved-stem Müller femoral prostheses. 5- to 10-year results of 545 total hip replacements. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1990;109:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Havinga ME, Spruit M, Anderson PG, van Dijk-van Dam MS, Pavlov PW, van Limbeek J. Results with the M. E. Müller cemented, straight-stem total hip prosthesis: a 10-year historical cohort study in 180 women. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Crawford RW, Evans M, Ling RS, Murray DW. Fluid flow around model femoral components of differing surface finishes: in vitro investigations. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:589-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kerboull M. The charnley-kerboull prosthesis. Berlin: Springer Verlag 1987; 13-17. |

| 16. | Breusch SJ, Lukoschek M, Kreutzer J, Brocai D, Gruen TA. Dependency of cement mantle thickness on femoral stem design and centralizer. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:648-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schweizer A, Riede U, Maurer TB, Ochsner PE. Ten-year follow-up of primary straight-stem prosthesis (MEM) made of titanium or cobalt chromium alloy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:353-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Maurer TB, Ochsner PE, Schwarzer G, Schumacher M. Increased loosening of cemented straight stem prostheses made from titanium alloys. An analysis and comparison with prostheses made of cobalt-chromium-nickel alloy. Int Orthop. 2001;25:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hamadouche M, Baqué F, Lefevre N, Kerboull M. Minimum 10-year survival of Kerboull cemented stems according to surface finish. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Howie DW, Middleton RG, Costi K. Loosening of matt and polished cemented femoral stems. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:573-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Howell JR, Blunt LA, Doyle C, Hooper RM, Lee AJ, Ling RS. In vivo surface wear mechanisms of femoral components of cemented total hip arthroplasties: the influence of wear mechanism on clinical outcome. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:88-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Smith RW, Walker RR. Femoral expansion in aging women: implications for osteoporosis and fractures. Science. 1964;145:156-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Poss R, Staehlin P, Larson M. Femoral expansion in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1987;2:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Noble PC, Box GG, Kamaric E, Fink MJ, Alexander JW, Tullos HS. The effect of aging on the shape of the proximal femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;31-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dorr LD, Faugere MC, Mackel AM, Gruen TA, Bognar B, Malluche HH. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone. 1993;14:231-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 665] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Clauss M, Luem M, Ochsner PE, Ilchmann T. Fixation and loosening of the cemented Muller straight stem: a long-term clinical and radiological review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1158-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;20-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |