Revised: November 16, 2012

Accepted: December 6, 2012

Published online: April 18, 2013

AIM: To evaluate whether walking ability recovers early after bipolar hemiarthroplasty (BHA) using a direct anterior approach.

METHODS: Between 2008 and 2010, 81 patients with femoral neck fracture underwent BHA using the direct anterior approach (DAA) or the posterior approach (PA). The mean observation period was 36 mo. The age, sex, body mass index (BMI), time from admission to surgery, length of hospitalization, outcome after discharge, walking ability, duration of surgery, blood loss and complications were compared.

RESULTS: There was no significant difference in the age, sex, BMI, time from admission to surgery, length of hospitalization, outcome after discharge, duration of surgery and blood loss between the two groups. Two weeks after the operation, assistance was not necessary for walking in the hospital in 65.0% of the patients in the DAA group and in 33.3% in the PA group (P < 0.05). As for complications, fracture of the femoral greater trochanter developed in 1 patient in the DAA group and calcar crack and dislocation in 1 patient each in the PA group.

CONCLUSION: DAA is an approach more useful for BHA for femoral neck fracture in elderly patients than total hip arthroplasty in terms of the early acquisition of walking ability.

- Citation: Baba T, Shitoto K, Kaneko K. Bipolar hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture using the direct anterior approach. World J Orthop 2013; 4(2): 85-89

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v4/i2/85.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v4.i2.85

The direct anterior approach (DAA) is an intermuscular approach to reach the hip joint using the distal part of the Smith-Petersen approach without muscle detachment[1-3]. This approach has been reported to be useful in total hip arthroplasty (THA) for hip osteoarthritis due to it facilitating recovery of walking ability early after the operation[2,4-8]. When bipolar hemiarthroplasty is performed for femoral neck fracture in the elderly, early recovery is important to prevent a decrease in activities of daily living (ADL)[9-11]. Therefore, assuming that walking ability recovers early after bipolar hemiarthroplasty using DAA, we performed a prospective study on the usefulness of DAA in comparison with the posterior approach (PA).

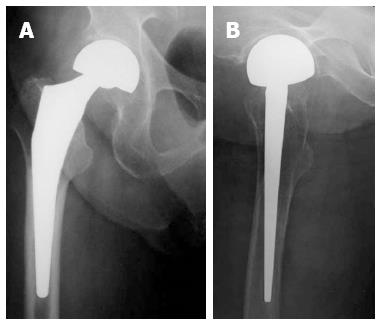

Between January 2008 and January 2010, 81 patients with femoral neck fracture underwent bipolar hemiarthroplasty using DAA or PA, and 79 of them were included as subjects after excluding patients with a pathological fracture. The patients were alternately assigned to the DAA group or PA group in the order they were hospitalized. The mean observation period was 36 mo (24-48 mo). As for the prosthesis type, the Centrax/Accolade TMZF (β titanium alloy: titanium-molybdenum-zirconium-iron) stem (Stryker) was used in all patients (Figure 1). Surgery was performed as soon as possible after admission. Anticoagulants/antiplatelet drugs were not suspended. The operators were 6 surgeons with 2-8 years clinical experience in the orthopedic department. The author (Baba T) played the role of a teaching assistant in all operations.

DAA was performed employing the method of Oinuma et al[2] using the distal part of the Smith-Petersen approach in the supine position on a standard surgical table. The fascia of the tensor fasciae latae muscle was incised at a site about 2 cm laterally to the skin incision to prevent lateral femoral cutaneous nerve injury and the intermuscular space between the tensor fasciae latae muscle and sartorius muscle was bluntly entered. The anterior articular capsule was exposed, incised and resected as much as possible to expose the femoral head. For stem insertion, the surgical table was extended so that the hip joint could be extended to 15°. The superior and posterior portions of the articular capsule were partly incised so that the greater trochanter could be elevated with a retractor. Finally, the size and stability were confirmed under fluoroscopy during the operation. PA was performed in the lateral recumbent position. The gluteus maximus muscle was divided along muscle fibers and short external rotators were detached. A T-shaped incision was made in the articular capsule and the femoral head was resected. Finally, the short external rotators and the articular capsule were sutured to the original position as much as possible.

In both groups, full weight bearing was permitted from the day after the operation. In the DAA group, no abduction pillow was applied. The PA group used an abduction pillow during rest on the bed for about 2 wk. An antibiotic was administered at the time of the introduction of anesthesia and at 3 hourly intervals thereafter (total of 3 times) on the day of the operation and twice a day for the subsequent 4 d. The drain was removed 2 d after the operation and fondaparinux as an anticoagulant for deep veins was administered at an appropriate dose according to the body weight and renal function for 14 d. The patients visited the hospital for examination 1 mo after discharge and underwent plain X-ray examination and clinical evaluation at 3 monthly intervals for 1 year and at 6 monthly intervals thereafter. When they were transferred to another hospital to continue rehabilitation, they visited our hospital 1 mo after the transfer and the subsequent schedule was the same as above.

The age, sex, body mass index (BMI), time from admission to surgery, length of hospitalization, outcome after discharge, walking ability, duration of surgery, blood loss and complications were compared.

Continuous data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test and Student’s t-test and data grouped into categories were analyzed with the chi-squared test. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

The DAA group consisted of 40 patients (7 males and 33 females) with a mean age of 76.7 ± 7.3 years. The PA group consisted of 39 patients (8 males and 31 females) with a mean age of 74.9 ± 7.7 years. Two patients in the DAA group died of liver cancer and myocarditis and 1 in the PA group died of renal failure. These deaths were not associated with the femoral neck fracture. The other patients were followed up to the final evaluation time point. There was no significant difference in the age, sex and BMI between the two groups (Table 1). Surgery was performed 2.9 d (mean) after admission in both the DAA group and the PA group. Surgery was performed within 2 d after admission in 24 of the 40 patients in the DAA group and 23 of the 39 patients in the PA group.

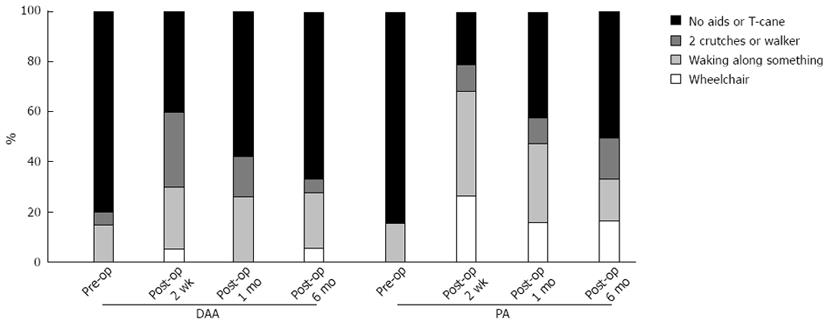

The mean hospitalization period was 29.9 (14-50) d in the DAA group and 29.3 (17-58) d in the PA group, showing no difference. Therefore, the place of residence at the time of injury and the place to which the patient was discharged from our hospital were investigated. In the DAA group, the former and latter were home and home, respectively, in 38 patients and a facility and facility in 1, and home and a rehabilitation hospital in 1. Of the 40 patients, 39 were discharged to the place of residence before injury. In the PA group, the former and latter places were home and home, respectively, in 21 patients and home and a rehabilitation hospital in 18. Of the 39 patients, only 21 were discharged to the place of residence before injury. Walking ability before injury and after the operation was classified into the following 4 categories: unaided walking (including walking using a T-cane because in our hospital we instruct patients to use a T-cane even when unaided walking is possible), walking using two crutches (including walkers for the elderly), walking along something (assisted walking) and use of a wheelchair (Figure 2). Two weeks after the operation, assistance was not necessary for walking in the hospital (unaided walking, walking using a T-cane, walking with 2 crutches) in 65% (26/40) of the patients in the DAA group and in 33.3% (13/39) in the PA group (Mann-Whitney U test; P < 0.05). After 6 mo, unaided walking or walking using a T-cane was possible in 67.5% (27/40) in the DAA group and in 66.6% (26/39) in the PA group, without a significant difference between the two groups. The duration of surgery was 65.3 ± 39 min in the DAA group and 76.7 ± 33 min in the PA group. The intraoperative blood loss was 121 ± 82 g in the DAA group and 146 ± 56 g in the PA group. Warfarin was administered in 3 patients in the DAA group and Bayaspirin in 3 in the DAA group and 5 in the PL group but these drugs were not suspended during the perioperative period.

As for complications, fracture of the apex of the femoral greater trochanter developed in 1 patient in the DAA group and calcar crack in 1 patient and dislocation in 1 in the PA group. Neither infection of the superficial layer or deep area nor fatal deep venous thrombosis was observed. No special treatment was performed for the fracture of the apex of the femoral greater trochanter. The calcar crack was reinforced by wiring as much as possible. The fracture of the apex of the femoral greater trochanter or calcar crack did not delay the initiation of weight bearing after the operation, presenting no special clinical problems.

To improve ADL for femoral neck fracture in the elderly, we paid attention to DAA as an intermuscular approach. Excellent results of THA using DAA have been reported[12-14]. DAA is advantageous for the early postoperative recovery of muscle strength and is associated with a low dislocation rate. However, it has also been reported that muscle strength 6-12 mo after the operation does not differ between DAA and other approaches[4,15]. Since THA is mostly performed for hip osteoarthritis, the long-term recovery of muscle strength is important and the advantage of DAA (early recovery of muscle strength) is not so marked. Rather than this advantage, the low dislocation rate may be useful for THA. On the other hand, in bipolar hemiarthroplasty in the elderly, it is important to use methods that: (1) does not induce dislocation, even in patients such as dementia patients with difficulty in recognizing contraindicated limb positions; and (2) facilitate early regaining of walking ability without a decrease in the preoperative muscle strength rather than the long-term recovery of muscle strength. In addition, less invasive, safe and accurate surgical methods may reduce peri- and postoperative complications, contributing to ADL improvement. Therefore, we performed this study, comparing two groups who were treated by DAA as an intermuscular approach or PA as an approach with muscle detachment using the same prosthesis system and who were similar in age and sex and the waiting period. As a result, the DAA group clearly showed a better walking ability early after the operation.

Dislocation after bipolar hemiarthroplasty is one of the complications, although the reported dislocation rate varies from 1.5% to 13.4%[16-20]. Risk factors of dislocation include difficulty in recognizing dislocation-inducing limb positions due to dementia and mental/neurological disorders, decreased muscle strength due to hemiplegia or Parkinson’s disease, and frequent falling. These risks cannot be avoided because this fracture mainly occurs in elderly people. Concerning the difference in the dislocation rate between surgical approaches, many studies have shown that the anterior approach is advantageous in reducing dislocation in THA[1,3], whereas Sierra RJ et al[18] reported no association between the dislocation rate after bipolar hemiarthroplasty and the surgical approach. In our study, dementia and Parkinson’s disease were observed in 5 and 1 patient, respectively, in the DAA group and 3 and 3 patients, respectively, in the PA group. The number of high-risk patients for dislocation was similar between the two groups but two episodes of posterior dislocation occurred in a patient with dementia in the PA group. After using a hip abduction orthosis, this patient did not develop dislocation. Dislocation-inducing limb positions in the PA group may involve a higher risk in bipolar hemiarthroplasty in elderly patients than in THA because patients have difficulty in adequately understanding these positions. Since dislocation-inducing limb positions after an operation using DAA rarely occur during ADL, few instructions regarding such positions are necessary.

Oinuma et al described patients appropriate for implantation of a THA by DAA system as: (1) females; (2) without obesity; (3) with osteoarthritis excluding Crowe 3 and 4; and (4) showing a wide range of motion[21,22]. When these criteria are applied to bipolar hemiarthroplasty, femoral neck fracture frequently occurs in females without deformation showing a normal range of motion. In our DAA group, the mean BMI was 20.1 and there were few obese patients. These conditions are appropriate for the use of DAA. In particular, using DAA, stem manipulation on the femoral side is considered to be difficult. However, since femoral neck fracture was not accompanied by flexion contracture or deformation, anterior transfer of the femur was straightforward in bipolar hemiarthroplasty compared with THA. Fracture of the apex of the greater trochanter in our study was clearly a surgical manipulation problem and adequate attention should have been paid to osteoporotic bone. Due to the surgical technique, it is necessary to select stems not occupying the medullary cavity and preserving the greater trochanter. Long straight stems are difficult to insert using DAA. The Accolade TMZF stem (Stryker) used in this study has a tapered wedge achieving stem fixation on the medial and lateral sides of the femoral medullary cavity in a wedge shape[23]. Since the anteroposterior width of the stem is narrow and rasping of the greater trochanter is not necessary, this stem could be readily used for DAA. Concerning tapered wedge fixation in patients with frail medullary cavity shapes or bone, the stem alignment tends to be flexed but this presents no clinical problems and satisfactory mid-term results have been reported[24,25]. Indeed, there were no clinical problems associated with the use of the Accolade stem in our patients.

In conclusion, DAA is an approach more useful for bipolar hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture in elderly patients than THA in terms of the early acquisition of walking ability due to muscle preservation and the low dislocation rate.

The direct anterior approach (DAA) is an intermuscular approach to reach the hip joint using the distal part of the Smith-Petersen approach without muscle detachment. This approach has been reported to be useful in total hip arthroplasty (THA) for hip osteoarthritis due to it facilitating recovery of walking ability early after the operation.

When bipolar hemiarthroplasty is performed for femoral neck fracture in the elderly, early recovery is important to prevent a decrease in activities of daily living.

Assuming that walking ability recovers early after bipolar hemiarthroplasty using DAA, the authors performed a prospective study on the usefulness of DAA in comparison with the posterior approach (PA).

DAA is an approach more useful for bipolar hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture in elderly patients than THA in terms of the early acquisition of walking ability due to muscle preservation and the low dislocation rate.

The authors treated femoral neck fracture cases treated bipolar hemiarthroplasty and compared between groups using the DAA and the group using the PA. The manuscript is neat. The concluded that DAA useful in elderly patients than PA in terms of the early acquisition of walking ability due to muscle preservation and anesthetic management during surgery in the supine position.

P- Reviewer Sakamoto A S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Matta JM, Shahrdar C, Ferguson T. Single-incision anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty on an orthopaedic table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:115-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Oinuma K, Eingartner C, Saito Y, Shiratsuchi H. Total hip arthroplasty by a minimally invasive, direct anterior approach. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19:310-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Siguier T, Siguier M, Brumpt B. Mini-incision anterior approach does not increase dislocation rate: a study of 1037 total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;164-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakata K, Nishikawa M, Yamamoto K, Hirota S, Yoshikawa H. A clinical comparative study of the direct anterior with mini-posterior approach: two consecutive series. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:698-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Klausmeier V, Lugade V, Jewett BA, Collis DK, Chou LS. Is there faster recovery with an anterior or anterolateral THA? A pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:533-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mayr E, Nogler M, Benedetti MG, Kessler O, Reinthaler A, Krismer M, Leardini A. A prospective randomized assessment of earlier functional recovery in THA patients treated by minimally invasive direct anterior approach: a gait analysis study. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2009;24:812-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kennon RE, Keggi JM, Wetmore RS, Zatorski LE, Huo MH, Keggi KJ. Total hip arthroplasty through a minimally invasive anterior surgical approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A Suppl 4:39-48. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Rachbauer F, Krismer M. [Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty via direct anterior approach]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20:239-251. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Schneider K, Audigé L, Kuehnel SP, Helmy N. The direct anterior approach in hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures. Int Orthop. 2012;36:1773-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Laflamme GY, Rouleau DM, Leduc S, Roy L, Beaumont E. The Timed Up and Go test is an early predictor of functional outcome after hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1175-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Taylor F, Wright M, Zhu M. Hemiarthroplasty of the hip with and without cement: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:577-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bertin KC, Röttinger H. Anterolateral mini-incision hip replacement surgery: a modified Watson-Jones approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;248-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Inaba Y, Dorr LD, Wan Z, Sirianni L, Boutary M. Operative and patient care techniques for posterior mini-incision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:104-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alecci V, Valente M, Crucil M, Minerva M, Pellegrino CM, Sabbadini DD. Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a direct anterior approach versus the standard lateral approach: perioperative findings. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Maffiuletti NA, Impellizzeri FM, Widler K, Bizzini M, Kain MS, Munzinger U, Leunig M. Spatiotemporal parameters of gait after total hip replacement: anterior versus posterior approach. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:407-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Eriksson K, Söderqvist A, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. A randomised controlled trial comparing bipolar hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement for displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:160-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rao JP, Vernoy TA, Allegra MP, DiPaolo D. A comparative analysis of Giliberty, Bateman, and Universal femoral head prostheses. A long-term follow-up evaluation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;188-196. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Sierra RJ, Schleck CD, Cabanela ME. Dislocation of bipolar hemiarthroplasty: rate, contributing factors, and outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:230-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suh KT, Kim DW, Lee HS, Seong YJ, Lee JS. Is the dislocation rate higher after bipolar hemiarthroplasty in patients with neuromuscular diseases? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1158-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Figved W, Opland V, Frihagen F, Jervidalo T, Madsen JE, Nordsletten L. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2426-2435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Hallert O, Li Y, Brismar H, Lindgren U. The direct anterior approach: initial experience of a minimally invasive technique for total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res. 2012;7:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Oinuma K, Tamaki T, Fukui Y, Kanayama R, Shiratuchi H. Surgical techniques and issues of THA using direct anterior approach-for shortening the learning curve. Nihon Jinkoukansetsu Gakkaishi. 2010;40:6-7. |

| 23. | Lettich T, Tierney MG, Parvizi J, Sharkey PF, Rothman RH. Primary total hip arthroplasty with an uncemented femoral component: two- to seven-year results. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:43-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Purtill JJ, Rothman RH, Hozack WJ, Sharkey PF. Total hip arthroplasty using two different cementless tapered stems. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;121-127. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Casper DS, Kim GK, Restrepo C, Parvizi J, Rothman RH. Primary total hip arthroplasty with an uncemented femoral component five- to nine-year results. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:838-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |