Revised: January 23, 2013

Accepted: February 4, 2013

Published online: April 18, 2013

Processing time: 138 Days and 23.3 Hours

AIM: To track the short-term neck narrowing changes in Birmingham metal-on-metal hip resurfacing (MOMHR) patients.

METHODS: Since 2001, the Center for Hip and Knee Replacement started a registry to prospectively collect data on hip and knee replacement patients. From June 2006 to October 2008, 139 MOMHR were performed at our center by two participate surgeons using Birmingham MOMHR prosthesis (Smith Nephew, United States). It is standard of care for patients to obtain low, anteriorposterior (LAP) pelvis radiographs immediately after MOMHR procedure and then at 3 mo, 1 year and 2 year follow up office visits. Inclusion criteria for the present study included patients who came back for follow up office visit at above mentioned time points and got LAP radiographs. Exclusion criteria include patients who missed more than two follow up time points and those with poor-quality X-rays. Two orthopaedic residency trained research fellows reviewed the X-rays independently at 4 time points, i.e., immediate after surgery, 3 mo, 1 year and 2 year. Neck-to-prosthesis ratio (NPR) was used as main outcome measure. Twenty cases were used as subjects to identify the reliability between two observers. An intraclass correlation coefficient at 0.8 was considered as satisfied. A paired t-test was used to evaluate the significant difference between different time points with P < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS: The mean NPRs were 0.852 ± 0.056, 0.839 ± 0.052, 0.835 ± 0.051, 0.83 ± 0.04 immediately, 3 mo, 1 year and 2 years post-operatively respectively. At 3 mo, NPR was significantly different from immediate postoperative X-ray (P < 0.001). There was no difference between 3 mo and 1 year (P = 0.14) and 2 years (P = 0.53). Femoral neck narrowing (FNN) exceeding 10% of the diameter of the neck was observed in only 4 patients (5.6%) at two years follow up. None of these patients developed a femoral neck fracture (FNF).

CONCLUSION: Femoral neck narrowing after MOMHR occurred as early as 3 mo postoperatively, and stabilized thereafter. Excessive FNN was not common in patients within the first two years of surgery and was not correlated with risk of FNF.

- Citation: Wang W, Geller JA, Hasija R, Choi JK, Jr. DAP, Macaulay W. Longitudinal evaluation of time related femoral neck narrowing after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. World J Orthop 2013; 4(2): 75-79

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v4/i2/75.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v4.i2.75

Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing (MOMHR) was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2006, buoyed by promising survivorship data from the United Kingdom[1]. This technique, primarily due to its bone conserving nature, has become an alternative to total hip arthroplasty in younger patients. Femoral neck narrowing, potentially posing as a risk factor for femoral neck fracture, is a complication unique to this type of arthroplasty; though at present, there is no consistent evidence showing correlation between neck narrowing and neck fracture after MOMHR.

The incidence of neck narrowing after MOMHR was reported from 77% to 98%[2-3]. Although the exact etiology of neck narrowing is still unknown, possible contributing factors for neck narrowing may include stress shielding, damage to the blood supply, bone necrosis in the residual femoral head, alteration in hip biomechanics or secondary to wear debris[5-12].

Spencer’s study showed neck narrowing after resurfacing may stabilize after 2 years[2]. Shimmin demonstrated that the mean time to fracture after MOMHR is 3 to 4 mo, while Cooke et al reported that bone mineral density is significantly decreased at 3 mo postoperatively and recovers back to normal thereafter[13,14]. As a result of this data it is unclear when exactly neck narrowing occurs and whether or not it had any impact as a risk factor for early femoral neck fracture with MOMHR. Thus the purpose of this study was to more closely evaluate the changes that occur in the femoral neck in MOMHR patients. We measured neck narrowing radiographically immediately after surgery and at 3 mo, 1 year and 2 years postoperatively. We hypothesized that neck narrowing occurs early after MOMHR and then stabilizes long before the 2 year time point.

This study was a retrospective longitudinal evaluation of prospectively collected patients’ data from the Center for Hip and Knee Replacement Registry. From June 2006 to October 2008, 139 MOMHR were carried out at our center by two senior surgeons using the Birmingham MOMHR prosthesis (Smith Nephew, Memphis, TN, United States). All operations were performed using a modified enhanced posterior soft tissue repair approach[15]. The components were fixed using an uncemented hydroxyapatite porous coated cobalt chrome acetabular component and a cemented femoral component. As a part of our standard of care, all patients had low anterior-posterior (LAP) pelvis radiographs immediately after MOMHR procedure and were advised follow-up X-rays at 3 mo, 1 year and 2 years post-operatively. All radiographs were taken with great toes in contact to maintain consistent femoral rotation.

Inclusion criteria for the present study were all patients who came back for follow up office visit at the above mentioned time points and obtained LAP radiographs. Exclusion criteria included patients who missed more than two follow up time points and those with poor-quality X-rays. Symmetry of the trochanter was evaluated qualitatively on all follow up radiographs to ensure identical femoral neck version. We had function follow up of all 139 MOMHR. None of them had femoral neck fracture or revision at 2 years time point. Seventyone hips were excluded due to lack of proper X-rays; 68 hips (61 patients) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included into the study. Out of these 49 (72%) were in men and 19 (28%) were in women. The mean age at the time of surgery was 50.6 ± 9.6 years, the average body mass index was 29.4 ± 5.2 kg/m2. The primary preoperative diagnosis was osteoarthritis in 53 (78%), osteonecrosis in 11 (16.2%), dysplasia in 2 (3%) and inflammatory arthritis in 2 (3%).

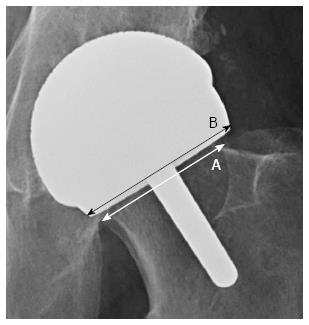

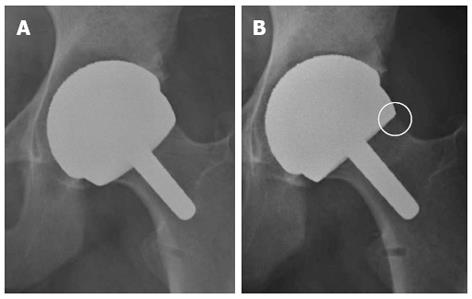

Neck-to-prosthesis ratio, as described by Spencer et al[2], was used as the main outcome measure. “A” is the diameter of the femoral neck exactly at the prosthesis; “B” is the diameter of the implant exactly at the level of its opening edge (Figure 1). By dividing A by B the neck-to-prosthesis ratio was calculated. The means of the ratios between the two observers was taken for statistical analysis. Neck narrowing was indicated by reduced ratio (A/B) over the period of time. Femoral neck narrowing greater than 10% was considered significant.

Two independent observers reviewed the X-rays at 4 time points, i.e., immediately after surgery, 3 mo, 1 year and 2 year. All the measurements were performed using Centricity Enterprise Web V3.0 (2006 GE Medical System) digital radiographic software. Twenty cases were used as subjects to calculate an intraclass correlation coefficient which evaluates the intra-observer and inter-observer reliability between the two observers (a value more than 0.8 was considered significant). After ensuring good reliability the remaining patients’ X-rays were analyzed.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS for Windows, Rel. 12.0.0, 2003; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). A paired t-test was used to evaluate the significant difference between different time points. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

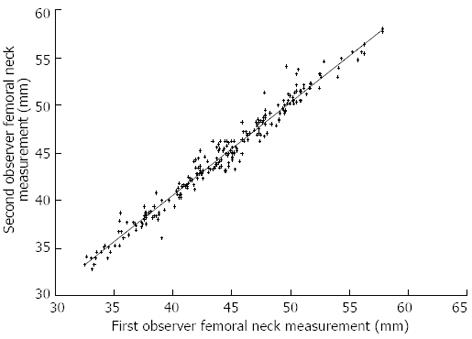

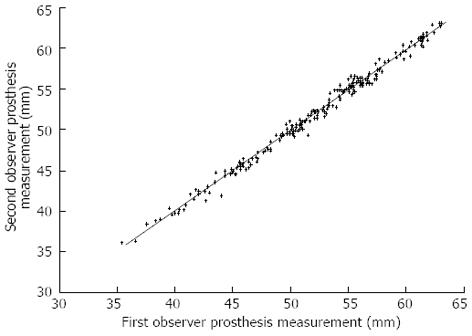

Intraclass correlation coefficient calculated to analyze the reliability of the intraobserver and interobserver radiological measurements of diameters of femoral neck and the femoral component showed significant degree of correlation (correlation coefficient = 0.924; 95%CI of 0.903-0.941) (Figures 2 and 3).

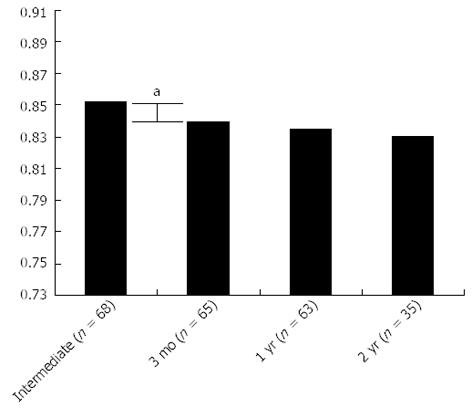

The neck-to-prosthesis ratios (NPRs) were 0.852 ± 0.056 immediately after surgery, 0.839 ± 0.052 at 3 mo, 0.835 ± 0.051 at 1 year and 0.83 ± 0.04 at 2 years post-operatively (Figure 4). When comparing to the immediate postoperative NPRs, the percent change was 1.9 ± 3.2 (0.05%-12.6%) at 3 mo, 1.9 ± 4.4 (0.1%-17%) at 1 year, and 3.6 ± 4.8 (0.07%-20%) at 2 years post-operatively. At 3 mo, femoral neck narrowing (FNN) was observed in 74% (48) of hips, which was significantly different from immediate postoperative X-ray (P < 0.001). Out of these 48 hips 23 were in men and 15 in women. There was no difference between neck to prosthesis ratio between 3 mo and 1 year (P = 0.14) and between 1 year and 2 years (P = 0.53). Excessive FNN, i.e., narrowing that exceeded 10% of the diameter of the neck, was observed in only 4 patients at two years follow up. None of these patients developed a femoral neck fracture.

This aim of this study was to evaluate the short term FNN after MOMHR. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal evaluation of time related FNN after MOMHR focusing on short term outcome. Previous studies have focused on neck narrowing at 2 years or more, and their results have consistently reported absence of significant neck narrowing after 2 years post-operatively[1-4,16]. Spencer et al[2] reported that neck narrowing occurs within the first 2 years after surgery with no significant progression observed to a follow up of 7 years. Hing et al[4] showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the neck diameter at 3 years and 5 years indicating that thinning had stabilized previous to the 3 years time point. Joseph et al[3] also found no significant neck thinning after 2 years. Results of our study demonstrate that FNN after Birmingham MOMHR prosthesis occurs as early as 3 mo postoperatively and the NPR stabilizes thereafter (Figure 5). Our results of early neck narrowing may be supported by observations of Cooke et al[14] who found that bone mineral density changes after resurfacing are mainly confined to femoral neck and that it reduces by 3 mo post-operatively but is recovered to normal by 12 mo with no significant change thereafter.

The incidence of neck narrowing in our cohort was 74% (48 hips). This was similar to what Hing et al[4] observed (125 hips; 77%) in their study on 163 Birmingham Hip Resurfacing arthroplasties but was less than that reported by Spencer et al[2] who found neck narrowing in 90% of prosthesis at 2 years post operatively. It is possible that the uncemented implant used in that study may result in a different loading pattern as compared to BHR. Joseph et al. did a comparative study examining both the Cormet 2000 in 35 cases and Birmingham Hip Resurfacing in 26 cases[3]. They observed neck narrowing in 98 % (60/61) of cases but found no statistical difference in the measurements between the two implant types. We also noticed that 15 out of 19 female had neck narrowing, while only 23 out of 49 male did (P = 0.017). One of the possible reason might be the femoral neck of female was significantly narrower than male. In our group the femoral neck diameter were 44.0 ± 3.5 mm and 37.7 ± 3.6 mm for male and female respectively. While the stem diameter of the femoral component is the same in spite of the size of the component, these results in the stem to neck ratio in female are greater than male. However, further researches were needed to investigate the effect of femoral neck diameter on neck narrowing.

Although the exact etiology of neck narrowing is still unknown, possible contributing factors for neck narrowing may include stress shielding, damage to the blood supply, bone necrosis in the residual femoral head, alteration in hip biomechanics or secondary to wear debris.

In the current literature, bone remodeling secondary to stress shielding after hip resurfacing has been studied by several finite element analyses[7-9]. Although bone remodeling is a feature of normal bone metabolism, hip resurfacing may result in stress shielding with resorption and narrowing of the femoral neck resulting from altered load. We believe that this resorption stabilizes by 3 mo; however, it requires further investigation.

Changes in blood supply to femoral head after hip resurfacing is controversial. Steffen et al[5] demonstrated compromised blood supply to the femoral head during hip resurfacing. Also, notching of the femoral neck during surgery has been shown to cause a reduction in blood flow of 50%[6]. In the retrieval analysis of failed Birmingham or Cormet resurfacing, Little et al[17] observed evidence of osteonecrosis in all but one case at revision. However, Howie et al[18] and Campbell et al[19] reported that retrieved femoral head maintained good blood supply and that avascular necrosis of femoral head is not a common cause of failure of resurfacing. The reason for this difference in observation may be attributed to different histological criteria used for determining osteonecrosis. It is still unclear if changing of blood supply plays a role in neck narrowing.

It has been shown that metal-on-metal articulations if malpositioned cause increased wear rates[10]. This wear induced debris can cause an inflammatory reaction and subsequent osteolysis which leads to neck thinning[10-12]. Also, in some patients hypersensitivity due to metal ion release may be a cause of neck thinning[20].

Although the clinical significance of neck narrowing is still unknown, the main concern is whether it could be predictive of future risk of femoral neck fractures. There is no consistent evidence in the literature showing that neck narrowing can lead to fracture. Shimmin did a national review of 3497 Birmingham hips which were inserted by 89 surgeons. Fracture of the femoral neck occurred in 50 patients, an incidence of 1.46%. They also found out that the mean time to fracture was 15.4 wk postoperatively. In our cohort, though we observed a 74% rate of neck narrowing, we did not have any fracture cases and therefore, we were not able to evaluate if there is correlation between neck narrowing and fracture.

We note the limitations of this study. First, as in all previous studies, we did not assess FNN in the sagittal plane. Computed tomography scan or roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis may provide more accurate information; however, routine use of these methods on every resurfacing patient was not performed for this investigation. Our measurements were recorded using digital radiographs which may have improved our accuracy compared to previous studies done using a conventional radiography[1,2,16]. To reduce errors, all observations were made twice by two independent observers and all values were expressed as ratios. Similar to previous studies, we showed that this method of measuring neck-prosthesis ratio is statistically reliable. We had an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.924. Second, this is a retrospective study. Only 68 out of 139 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Although 96% (65/68) and 93% (63/68) patients had 3-mo and 1-year data, only 51% (35/68) had 2-year data. Selection bias may affect the result. Thirdly, the sample size of this study is relatively small. Potentially, this study could be under powered.

In conclusion, our study shows that neck narrowing occurs as early as 3 mo after MOMHR and is generally not progressive for up to 2 years as was previously believed. This pattern of early neck narrowing may be explained by bone adoption to initial stress shielding of the neck below the implant. Further study is required to determine the exact cause of this early neck narrowing. In our study, thinning of the femoral neck did not progress to any adverse clinical consequences and we are currently unsure of its clinical significance. It still remains to be seen whether patients with FNN may be more susceptible to femoral neck fracture.

Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing (MOMHR) was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2006, buoyed by promising survivorship data from the United Kingdom. This technique, primarily due to its bone conserving nature, has become an alternative to total hip arthroplasty in younger patients. Femoral neck narrowing, potentially posing as a risk factor for femoral neck fracture, is a complication unique to this type of arthroplasty.

The incidence of neck narrowing after MOMHR was reported from 77% to 98%. Although the exact etiology of neck narrowing is still unknown, possible contributing factors for neck narrowing may include stress shielding, damage to the blood supply, bone necrosis in the residual femoral head, alteration in hip biomechanics or secondary to wear debris. As a result of this data it is unclear when exactly neck narrowing occurs and whether or not it had any impact as a risk factor for early femoral neck fracture with MOMHR.

This study was to more closely evaluate the changes that occur in the femoral neck in MOMHR patients. The authors measured neck narrowing radiographically immediately after surgery and at 3 mo, 1 year and 2 years postoperatively. The authors hypothesized that neck narrowing occurs early after MOMHR and then stabilizes long before the 2 year time point.

This pattern of early neck narrowing may be explained by bone adoption to initial stress shielding of the neck below the implant. In this study, thinning of the femoral neck did not progress to any adverse clinical consequences and we are currently unsure of its clinical significance. It still remains to be seen whether patients with femoral neck narrowing may be more susceptible to femoral neck fracture.

The manuscript is very interesting and can be accepted with minor corrections that are reported through the text.

P- Reviewer Saverio A S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | McMinn D, Treacy R, Lin K, Pynsent P. Metal on metal surface replacement of the hip. Experience of the McMinn prothesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;S89-S98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Spencer S, Carter R, Murray H, Meek RM. Femoral neck narrowing after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:1105-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Joseph J, Mullen M, McAuley A, Pillai A. Femoral neck resorption following hybrid metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a radiological and biomechanical analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1433-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hing CB, Young DA, Dalziel RE, Bailey M, Back DL, Shimmin AJ. Narrowing of the neck in resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: a radiological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1019-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Steffen RT, Smith SR, Urban JP, McLardy-Smith P, Beard DJ, Gill HS, Murray DW. The effect of hip resurfacing on oxygen concentration in the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1468-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Beaulé PE, Campbell PA, Hoke R, Dorey F. Notching of the femoral neck during resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: a vascular study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Watanabe Y, Shiba N, Matsuo S, Higuchi F, Tagawa Y, Inoue A. Biomechanical study of the resurfacing hip arthroplasty: finite element analysis of the femoral component. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:505-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ong KL, Kurtz SM, Manley MT, Rushton N, Mohammed NA, Field RE. Biomechanics of the Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1110-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gupta S, New AM, Taylor M. Bone remodelling inside a cemented resurfaced femoral head. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2006;21:594-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shimmin A, Beaulé PE, Campbell P. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:637-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Campbell P, Beaulé PE, Ebramzadeh E, Le Duff MJ, De Smet K, Lu Z, Amstutz HC. The John Charnley Award: a study of implant failure in metal-on-metal surface arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:35-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Campbell PA, Wang M, Amstutz HC, Goodman SB. Positive cytokine production in failed metal-on-metal total hip replacements. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:506-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shimmin AJ, Back D. Femoral neck fractures following Birmingham hip resurfacing: a national review of 50 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:463-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cooke NJ, Rodgers L, Rawlings D, McCaskie AW, Holland JP. Bone density of the femoral neck following Birmingham hip resurfacing. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:660-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Macaulay W, Colacchio ND, Fink LA. Modified Enhanced Posterior Soft Tissue Repair In A Negligible Dislocation Rate After Hip Resurfacing. Oper Tech Orthop. 2009;19:163-168. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lilikakis AK, Vowler SL, Villar RN. Hydroxyapatite-coated femoral implant in metal-on-metal resurfacing hip arthroplasty: minimum of two years follow-up. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:215-222, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Little CP, Ruiz AL, Harding IJ, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Murray DW, Athanasou NA. Osteonecrosis in retrieved femoral heads after failed resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:320-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Howie DW, Cornish BL, Vernon-Roberts B. The viability of the femoral head after resurfacing hip arthroplasty in humans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;171-184. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Campbell P, Mirra J, Amstutz HC. Viability of femoral heads treated with resurfacing arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:120-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Willert HG, Buchhorn GH, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Köster G, Lohmann CH. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:28-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |