Revised: October 28, 2011

Accepted: January 1, 2012

Published online: January 18, 2012

AIM: To identify factors that affect patient response rates to preoperative functional surveys in hip and knee arthroplasty patients.

METHODS: From May 2008 to March 2009, 247 patients were scheduled more than 4 wk in advance for hip or knee arthroplasty by one of two participating surgeons at our center. A personalized questionnaire comprised of the Short Form 12 (SF-12) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Index was mailed to patients at random time points ranging from 7 to 101 d prior to surgery. Nine independent factors were documented prospectively, including age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, type of surgery, surgeon, days prior to surgery (DPS) of survey mailing, WOMAC score and SF-12 score. The date of the completed survey receipt was also documented. For non-responders, the surveys were completed with the research team at the hospital upon admission. Multivariate regression and χ2 analysis were performed with Statistical Analysis Software software.

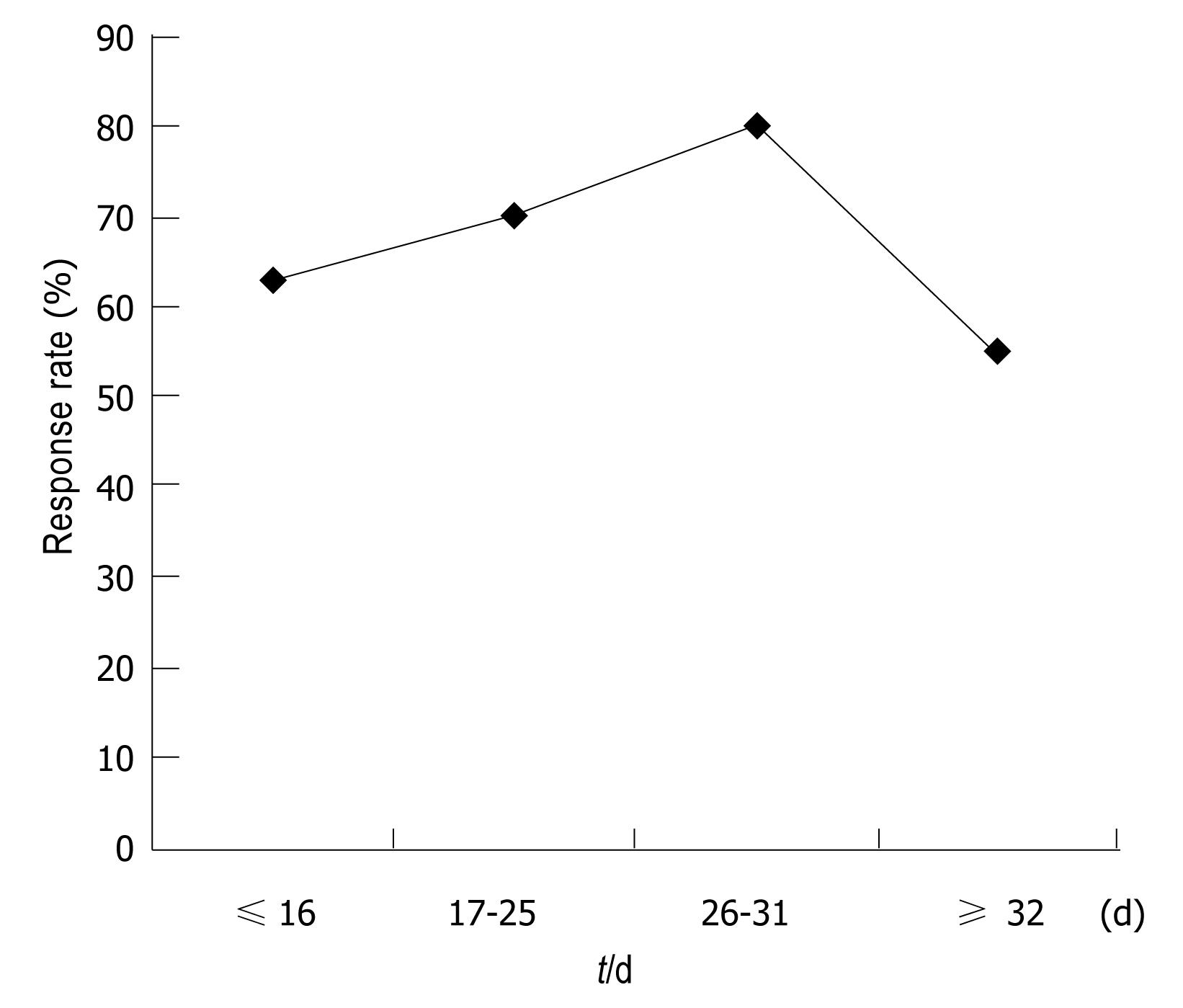

RESULTS: DPS was the only factor that affected patient response. Mailing surveys 26 d to 31 d prior to surgery dates led to a peak response rate of 80% that was significantly higher (P < 0.023) than response rates for patients who were mailed their surveys ≤ 16 d (62.5%), 17 d to 25 d (70%) or ≥ 32 d prior to surgery (55%). No other factors, including preoperative WOMAC and SF-12 scores, significantly influenced response behavior.

CONCLUSION: The DPS was independently the most significant predictor of response rates for pre-operative functional data among patients scheduled for hip and knee arthroplasty.

- Citation: Wang W, Geller JA, Kim A, Morrison TA, Choi JK, Macaulay W. Factors affecting response rates to mailed preoperative surveys among arthroplasty patients. World J Orthop 2012; 3(1): 1-4

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v3/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v3.i1.1

Patient-completed questionnaires are widely used in the collection of clinical data in virtually all orthopedic subspecialties. A variety of patient self-reported outcome measures have been developed and utilized in each respective orthopedic discipline to assess outcome of orthopedic procedures, such as lower extremity total joint arthroplasty[1-4]. Mailing self-reported outcome instruments is cost-effective for physicians and convenient for most patients[5]. This popular method of obtaining outcome measures, however, is limited by survey non-responders who adversely affect data validity[6]. Mailed surveys may be preferable for hip and knee arthroplasty patients who are demographically older and less likely to respond to internet or computer driven surveys. Additionally, paper surveys are often preferable as they are more Health Insurance Portability and Privacy Act (HIPAA) compliant.

Many studies have investigated strategies to improve patient response rates to postal questionnaires. A 2007 Cochrane Database review of 372 randomized control trials evaluated 98 factors that could potentially increase response rates. This study found that monetary incentives, recorded delivery, a teaser on the envelope and an interesting questionnaire topic doubled the odds of response rates, while pre-notification, follow-up contact, unconditional incentives, shorter questionnaires, providing a second copy of the questionnaire at follow-up, mentioning an obligation to respond and university sponsorship significantly increased the odds of response[7]. Response rates among lower extremity total joint arthroplasty patients in particular are also influenced by immutable factors such as postoperative outcomes. Non-responders following knee arthroplasty were found to have poorer outcomes than responders in two separate studies[8,9].

All aforementioned studies have examined ways to improve postoperative patient follow-up with mailed surveys. However, no such study on preoperative data collection exists in the literature. Preoperative general health and disease-specific assessments are equally important in that they provide essential baseline data for orthopedic outcomes research. This is an essential aspect to measuring the improvement that a surgical intervention may impart and how effective and reproducible it may be. Like postoperative follow-up questionnaires, preoperative surveys are also mostly mailed to patients for self-administration. The external and internal motivations and incentives for patients to complete self-administered surveys prior to orthopedic surgery, however, may be very different than those following surgery. Therefore, identifying factors that influence patient response rates prior to surgery is both novel and relevant to optimizing the validity of outcomes measures and further characterizing response behavior.

In this study, we prospectively evaluated the preoperative response behavior of completing a self-administered mail survey prior to undergoing routine knee and hip arthroplasty based on nine social, functional and logistical factors hypothesized to influence response rates.

From May 2008 to March 2009, 247 patients were scheduled more than 4 wk in advance for lower extremity joint arthroplasty, including total hip arthroplasty, total hip resurfacing, total knee arthroplasty, unicondylar knee arthroplasty and bicompartment knee arthroplasty, by two participating surgeons at our center. These patients comprised our prospective study cohort. A 53-item questionnaire comprised of the Short-Form 12 (SF-12) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Index of osteoarthritis score as well as a personalized, signed letter explaining the questionnaire’s purpose was enclosed in a stamped, hand-written envelope. The questionnaire and accompanying letter were mailed once to patients at random time points ranging from 7 to 101 d prior to surgery. Patients were instructed to return their completed surveys in non-stamped, pre-addressed envelopes included with the survey. No follow-up mailing or telephone calls were attempted with any patients. The date of completed survey receipt through the mail was also documented. For non-responders, the surveys were completed with the research team at the hospital on the day of admission.

Nine independent factors were documented prospectively, including age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, type of surgery, surgeon, days prior to surgery (DPS) of survey mailing, WOMAC score and SF-12 score. DPS was initially divided into ≤ 7 d, 8-10 d, 11-13 d, 14-16 d, 17-19 d, 20-22 d, 26-28 d, 29-31 d, 32-34 d and ≥ 35 d. It was then categorized by ≤16 d, 17-25 d, 26-31 d and ≥ 32 d for further statistical analysis.

Multivariate regression analysis was used to initially compare the effect of the nine aforementioned factors hypothesized to influence response rate. χ2 analysis was subsequently used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software 9.2 version (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

The overall preoperative response rate was 70%, with 173 out of 247 patients responding. At baseline, responders and non-responders did not differ with respect to age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, type of surgery or surgeon (Table 1). Moreover, responders and non-responders had similar SF-12 physical subscores (P = 0.41), SF-12 mental subscores (P = 0.7875) and WOMAC score physical component (P = 0.51). DPS was the only factor in this investigation that affected patient response rates. Further analysis with the chi-square test (Figure 1) revealed that mailing surveys 26 d to 31 d prior to surgery dates led to a peak response rate of 80% that was significantly higher (P < 0.023) than response rates for those who were mailed their surveys ≤ 16 d (63%), 17 d to 25 d (70%) or ≥ 32 d prior to surgery (55%).

| Responders | Non-responders | Total | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 63.24 ± 12.89 | 63.89 ± 13.91 | 63.44 ± 13.18 | 0.7237 |

| Gender (%) | Male 75/173 (43.35) | Male 38/74 (51.35) | Male 113/247 (45.7) | 0.2495 |

| Ethnicity (%) | White 103/173 (59.54) | White 53/74 (71.6) | White 156/247 (63.2) | 0.0718 |

| Marital status (%) | Married 93/173 (53.76) | Married 37/74 (50) | Married 130/247 (52.6) | 0.5898 |

| Type of surgery (%) | Hip 88/173 (50.87) | Hip 38/74 (51.35) | Hip 126/247 (51) | 0.9447 |

| Surgeon (%) | M 72/173 (41.62) | M 35/74 (37.3) | M 107/247 (43) | 0.4114 |

| SF-12 physical | 30.04 ± 7.75 | 31.11 ± 10.16 | 30.30 ± 8.40 | 0.4074 |

| SF-12 mental | 49.24 ± 11.95 | 48.74 ± 11.49 | 49.12 ± 11.8 | 0.7875 |

| WOMAC | 47.30 ± 21.42 | 45.11 ± 22.69 | 46.76 ± 21.7 | 0.5122 |

In this study, we evaluated the response rates to self-administered questionnaires mailed prior to surgery among patients scheduled to undergo routine lower extremity total joint arthroplasty. To our knowledge, this has not been done for pre-operative patient outcomes measures. Among nine social, functional and logistical factors evaluated, the timing of questionnaire mailing prior to surgery was the only significant determinant of response behavior. Specifically, mailing of surveys 26 d to 31 d prior to surgery led to a peak response rate of 80% that was significantly higher than response rates outside this time period. Twenty-six to thirty-one days may afford patients the most amount of time or be most convenient to complete surveys while mentally anticipating and physically preparing for upcoming surgery. It is possible that earlier mailings may have a greater chance of being lost, while later mailings may not be completed in time.

Preoperative general health status and function did not influence response behavior. It was presumed that given their need for lower extremity total joint arthroplasty, all patients were likely to have had similar significant disability that led them to schedule elective surgery. Therefore, factors other than physical pain, disability and function were suspected to affect response rate.

Surprisingly, our data showed many socioeconomic factors previously documented to affect response behavior in the literature did not affect response rate among responders to our questionnaire. Although socioeconomic status and literacy have been strongly correlated across ethnicities, our data did not show any significant correlation between ethnicity and response rates (Table 1). Marital status also did not affect the response rate despite its perceived role as a major social behavioral determinant (Table 1).

There were several limitations to this study that may affect the applicability of its findings. Firstly, there was no control group of patients to compare the behavior of lower extremity arthroplasty patients to that of the general population or other surgical patient populations both within and outside of orthopedic surgery. Secondly, there may be an as of yet unknown effect of our relatively limited sample size of 247 consecutive cases. However, although the sample size needed for an adequately powered factor analysis remains a controversial topic, there is no explicit recommendation in the literature about sample size. Instead, there is a wide range of what is considered to be adequate sample sizes. Costello and Osborne[10] found that the majority of studies (62.9%) in peer-reviewed journals performed factor analyses with subject to variable ratios of 10:1 or less, with no trend towards journals with higher impact factors using higher ratios. Thus, with a subject to variable ratio of greater than 25:1, our sample size conferred adequate power for the multivariate regression analysis.

The present data show that optimal timing of patient-completed survey mailing at 4 wk prior to surgery yielded a higher response rate. Although this may not always be possible, i.e., some patients will be scheduled less than 31 d prior to surgery, this data may be helpful to researchers who decide upon resource allocation. Preoperative function and social factors may be less important than perceived as was demonstrated in this investigation. Nevertheless, identifying factors that determine mailed survey response rate prior to surgery is important to decrease response bias and to improve the validity of both preoperative and postoperative data interpretation.

Patient-completed questionnaires are widely used in the collection of clinical data in virtually all orthopedic subspecialties. Mailing self-reported outcome instruments is cost-effective for physicians and convenient for most patients. Preoperative general health and disease-specific assessments provide essential baseline data for orthopedic outcomes research. However, this popular method is limited by survey non-responders who adversely affect data validity. There is no information in the literature on the success of this approach to data collection.

Many studies have investigated strategies to improve patient response rates to postal questionnaires and found many factors may affect the response rate. Response rates are also influenced by immutable factors such as postoperative outcomes. All previous studies have examined ways to improve postoperative patient follow-up with mailed surveys. However, no such study on preoperative data collection exists in the literature. Preoperative general health and disease-specific assessments are equally important in that they provide essential baseline data for orthopedic outcomes research. This is an essential aspect to measuring the improvement that a surgical intervention may impart and how effective and reproducible it may be. In this study, the authors prospectively evaluated the preoperative response behavior of completing a self-administered mail survey prior to undergoing routine knee and hip arthroplasty based on nine social, functional and logistical factors hypothesized to influence response rates.

This prospective evaluation demonstrated that the days prior to surgery was independently the most significant predictor of response rates for pre-operative functional data among patients scheduled for hip and knee arthroplasty. This data suggests that response rate may be significantly increased by selecting the optimal time to mail surveys.

This is a well designed, well written, well structured paper, addressing the yet not studied issue of patient's response behavior regarding preoperative patients derived outcome score questionnaires. It has a simple but important message for orthopedic outcome studies. The main study objective is relevant and useful for future research. The discussion is focused and well structured as well.

Peer reviewers: Dror Lakstein, MD, Consultant Orthopaedic surgeon, Hip and Knee arthroplasty service, Orthopaedic Department, E. Wolfson medical center, Holon, Israel; Lucian Bogdan Solomon, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma, Level 4, Bice Buiding, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Bourne RB. Measuring tools for functional outcomes in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2634-2638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Soohoo NF, Vyas RM, Samimi DB, Molina R, Lieberman JR. Comparison of the responsiveness of the SF-36 and WOMAC in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1168-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wylde V, Blom AW, Whitehouse SL, Taylor AH, Pattison GT, Bannister GC. Patient-reported outcomes after total hip and knee arthroplasty: comparison of midterm results. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:210-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:963-974. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sethuraman V, McGuigan J, Hozack WJ, Sharkey PF, Rothman RH. Routine follow-up office visits after total joint replacement: do asymptomatic patients wish to comply? J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sheikh K, Mattingly S. Investigating non-response bias in mail surveys. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1981;35:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, Kwan I, Cooper R. Methods to increase response rates to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;MR000008. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kwon SK, Kang YG, Chang CB, Sung SC, Kim TK. Interpretations of the clinical outcomes of the nonresponders to mail surveys in patients after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim J, Lonner JH, Nelson CL, Lotke PA. Response bias: effect on outcomes evaluation by mail surveys after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:15-21. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis; four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Research Evaluation. 2005;10:1-9. |