Published online May 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i5.104425

Revised: April 6, 2025

Accepted: April 28, 2025

Published online: May 18, 2025

Processing time: 147 Days and 18.7 Hours

Low back pain (LPB) is a common and impactful health concern globally, affecting individuals across various demographics and imposing a significant burden on the health care system. Nonspecific chronic LBP (NCLBP), characterized as pain lasting over 12 weeks without an identifiable cause, leads to notable functional limitations and reduced quality of life. Traditional rehabilitation programs, often focusing on dynamic exercises for lumbar strengthening, typically do not target the deep stabilizing muscles crucial for lumbar support and effective recovery. Multi-angular isometric lumbar exercise (MAILE) offers a low-impact method for strengthening lumbar stabilizers through multi-angular isometric contractions, reducing risks from dynamic movements. This article examines MAILE’s potential in addressing motor control dysfunctions in NCLBP, highlighting studies on lumbar muscle activation, core stability, and isometric exercises. The article explores the prevalence and socioeconomic impact of NCLBP in the Middle East, highlighting the need for affordable treatment options in areas like Qatar and Saudi Arabia. This article aims to validate the efficacy of MAILE in reducing pain, enhancing mobility, and improving lumbar stability, offering a valuable option for NCLBP management. Future research should focus on large-scale clinical trials to substantiate these findings and guide clinical practice.

Core Tip: This article underscores the promising therapeutic potential of multi-angular isometric lumbar exercise (MAILE) for managing nonspecific chronic low back pain. MAILE utilizes a low-impact, multi-angle isometric approach that effectively targets deep lumbar stabilizers, addressing motor control dysfunction without the risks associated with dynamic movements. Key benefits of MAILE include reduced pain, improved mobility, and enhanced lumbar stability. Nevertheless, further high-quality research is required to assess its efficacy, safety, and long-term advantages. Future studies must address methodological shortcomings to provide stronger evidence for clinical integration. Large-scale clinical trials are essential to validate these findings.

- Citation: Syed Y, Hassan MA, Kalayil RM, Othman OA, Mekkodathil A, El-Menyar A. Promising technique for managing nonspecific chronic low back pain using multi angular isometric lumbar exercise. World J Orthop 2025; 16(5): 104425

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i5/104425.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i5.104425

Low back pain (LBP) is defined as discomfort located between the costal margin and the inferior gluteal folds, occasionally radiating into the legs[1]. As a prevalent global health concern, LBP affects people of all ages and is one of the most common complaints in clinical settings. Approximately one in four adults seek treatment for LBP within six months, highlighting its widespread nature and the critical need for effective management strategies. While many acute cases resolve within a year, about one in ten become chronic conditions, causing persistent symptoms that can significantly impair daily life[2]. Nonspecific chronic LBP (NCLBP) is characterized by pain lasting over 12 weeks without a specific, identifiable cause, such as a fracture, infection, or tumor. This type of pain is often debilitating, diminishes the quality of life, and limits daily activities, sometimes leading to psychological distress. Muscle dysfunction, especially in lumbar stabilizers like the transversus abdominis and multifidus muscles, plays a significant role in the persistence of NCLBP symptoms. Effective management of NCLBP requires addressing these deep muscle deficits to prevent recurrence and improve outcomes.

Conventional exercise programs, including dynamic strengthening, stretching, and aerobic conditioning, may provide some relief; however, they often fail to target the deeper stabilizing muscles of the lumbar spine. These dynamic movements can also be unsuitable for individuals experiencing pain, instability, or movement-related fear, as they may exacerbate symptoms in some cases[3]. Physical therapy programs are frequently the first-line treatment for chronic lower back pain, featuring guided therapeutic exercises aimed at strengthening the lower back muscles and conditioning the spinal tissues and joints. The primary objectives of physical therapy are pain reduction, improved function, increased flexibility, and long-term maintenance to prevent the recurrence of back issues through ongoing exercises. These programs generally include core-strengthening exercises to support the spine and alleviate pain, lumbar stabilizing exercises to enhance spinal stability, and stretching exercises to increase flexibility and relieve muscle tension. By focusing on these essential elements, physical therapy plays a vital role in managing chronic LBP and promoting long-term spinal health[4].

Comprehensive rehabilitation programs adopt a multidisciplinary approach to treat chronic LBP, incorporating a variety of therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes. These programs often consist of physical therapy to strengthen the lower back, pain management through physiotherapeutic modalities or medications, behavioral counseling to develop coping strategies, and social support to address broader well-being issues. Designed to educate patients about proper back care, pain management, and the prevention of exacerbating factors, these programs are especially beneficial for individuals who have not responded to conventional treatments or who have undergone unsuccessful back surgeries. Often referred to as functional restoration programs, they aim to help patients regain normal daily function by focusing on functional improvement, effective pain management, psychological support, and overcoming challenges associated with traditional rehabilitation methods[5].

While traditional rehabilitation programs offer several benefits, they also present limitations in key areas. A significant drawback is their ineffectiveness in targeting deep stabilizing muscles, such as the transversus abdominis and multifidus, which are vital for lumbar stability. Conventional exercises primarily focus on surface muscles, often neglecting these deeper stabilizers. Furthermore, the dynamic movements involved in traditional exercises can pose risks, especially for individuals experiencing pain, spinal instability, or movement-related fear. Another challenge is the accessibility and adherence to these programs, as some require specialized equipment or involve prolonged, intensive routines that may be difficult for patients to follow consistently. These limitations underscore the need for alternative approaches that ensure effective muscle activation, minimal risk of exacerbation, and greater accessibility to encourage long-term adherence.

The principle of multi-angle exercises involves using isometric contractions at various angles to activate all muscle fibers, promoting balance and comprehensive strengthening. These contractions stabilize muscles without joint movement, effectively targeting deep lumbar stabilizers while minimizing the risk of injury. The foundation of multi-angle exercises is based on biomechanics, where engaging muscles at different angles optimizes their activation, particularly for crucial lumbar stabilizers like the transversus abdominis and multifidus. Enhanced motor control also plays a vital role in improving spinal stability by training muscles in multiple positions, which is essential for managing NCLBP. Unlike dynamic exercises, which may exacerbate pain and instability, multi-angle isometric exercises reduce the risk of aggravation, making them a safer option for patients with NCLBP.

The application of multi-angular isometric lumbar exercise (MAILE) focuses on targeted muscle activation, where controlled isometric contractions at various angles strengthen lumbar stabilizers. A structured progression of exercises gradually increases in complexity, helping patients build strength and stability without overloading the muscles. Furthermore, the practical implementation of MAILE makes it highly accessible, as it requires no specialized equipment, allowing patients to integrate it into their daily routines for long-term NCLBP management. MAILE represents an innovative therapeutic approach designed to address existing gaps in treatment. It employs isometric contractions without joint movement to minimize the risk of aggravation while strengthening the lumbar muscles across various angles, thereby enhancing stability and strength. This method shows particular promise for patients with NCLBP in the Middle East, where high prevalence rates and unique occupational and cultural factors contribute to the burden of NCLBP. For example, the prevalence of NCLBP in Saudi Arabia ranges from 18.8% to 53.5%, with significant implications for workforce productivity[6]. In Qatar, approximately 59.2% of primary care patients report experiencing LBP, highlighting the need for effective and accessible preventive and rehabilitative strategies[7].

Clinical evidence suggests that MAILE is an effective treatment for NCLBP, offering benefits such as pain reduction, enhanced muscle strength, and alleviation of functional disability. MAILE has shown positive results in patients with underlying conditions, including degenerative disc disease, lumbar osteoarthritis, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and hypermobility syndrome. Unlike many traditional rehabilitation programs, MAILE provides symptom relief without requiring prolonged, intensive exercise. As such, it offers a practical alternative that may match or even exceed the effectiveness of current treatment methods, with the potential for rapid recovery times and improved overall outcomes. This article aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of MAILE in managing NCLBP by examining its impact on pain reduction, muscle strength, functional improvement, and overall recovery in affected patients.

The primary aim of this article was to evaluate the effectiveness of MAILE in improving motor control dysfunction in patients with NCLBP by examining key outcome measures such as pain reduction, enhanced mobility, and improved muscle coordination. Additionally, one of the key advantages of MAILE therapy is its cost-effectiveness. MAILE exercises do not require specialized equipment, significantly reducing the initial investment for healthcare providers and patients. Unlike traditional rehabilitation programs, which often involve expensive machines, weights, and other equipment that require maintenance, MAILE can be performed using only body weight and minimal resources. This simplicity lowers the overall cost of therapy.

Furthermore, by effectively managing NCLBP, MAILE may help reduce the frequency of flare-ups and complications. As a result, patients may need fewer medical consultations, imaging studies, and invasive interventions like injections or surgeries, leading to substantial savings in healthcare costs over time. MAILE also lends itself well to a self-managed home exercise program, reducing the need for frequent visits to physical therapy clinics. Patients performing exercises at home can save on both time and costs associated with therapy sessions while improving adherence and outcomes. Moreover, effective management of NCLBP through MAILE can help prevent the recurrence of symptoms, thereby reducing the long-term costs related to chronic pain management. This includes savings on medications, additional physical therapy sessions, and the potential loss of productivity due to ongoing pain and disability.

In addition to being cost-effective, MAILE therapy offers significant time-efficiency benefits. The exercises are designed to be quick and effective, with each session typically lasting a shorter duration than traditional dynamic exercises. This shorter duration makes it easier for patients to incorporate the exercises into their daily routines without requiring a significant time commitment. The simplicity of MAILE exercises allows for quick implementation. Patients can learn the exercises in just a few sessions with a physical therapist and then continue them independently at home. This approach reduces the time spent on therapy and accelerates the rehabilitation process. Moreover, many patients experience immediate benefits, such as pain reduction and improved stability, providing quick feedback and motivating them to adhere to the program. This leads to faster recovery, enabling patients to spend less time dealing with chronic pain.

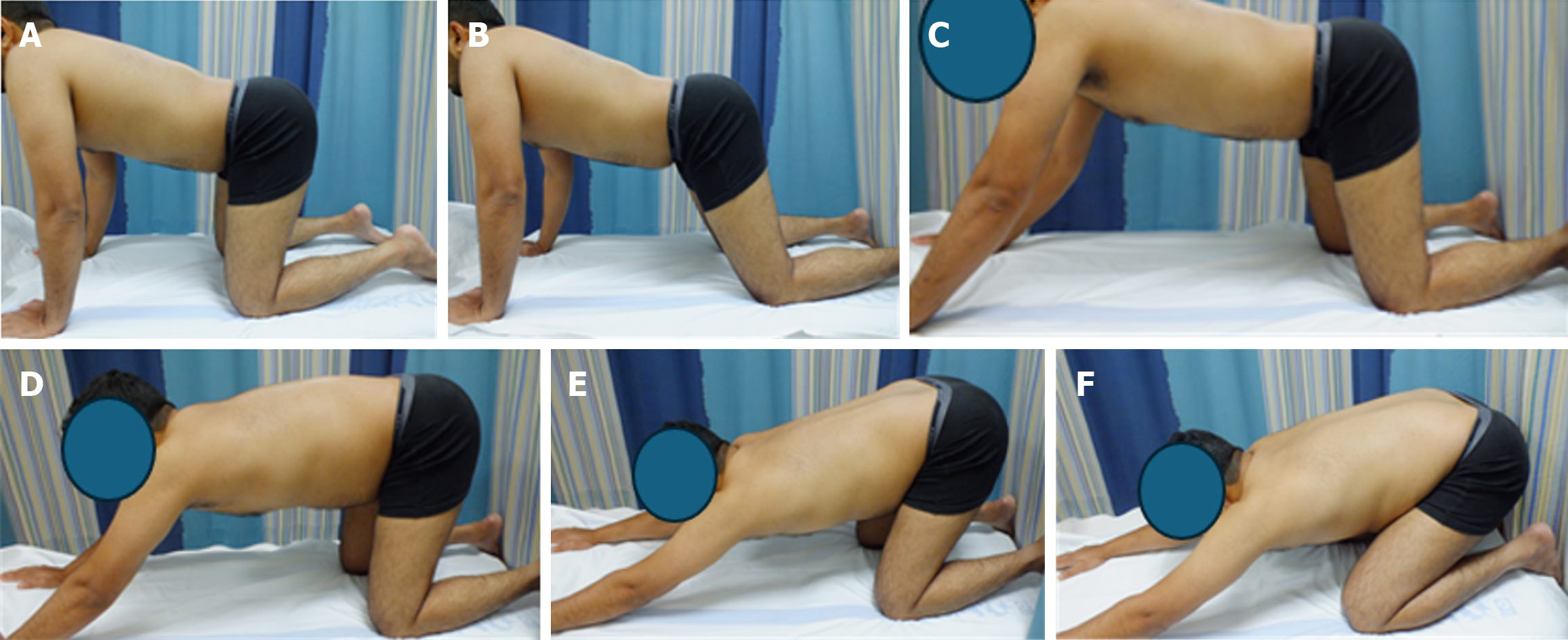

Finally, the flexibility of MAILE exercises enhances their time efficiency. Patients can perform the exercises anywhere and at any time without needing a gym or specialized equipment. This convenience allows for greater consistency and adherence, contributing to more effective and time-saving rehabilitation. This is particularly true for a self-managed home exercise program that encourages adherence due to its simplicity and lack of equipment requirements. Additionally, this review assessed the rehabilitative impact of MAILE in addressing structural impairments in the spine and pelvis, facilitating quick recovery and return to daily activities. Tables 1 and 2 describe the MAILE technique for the lumbopelvic hip complex and its utility in different positions. Figure 1 demonstrate the proposed exercises.

| Component | Details |

| Fundamental start position | Four-point kneeling; hands directly under shoulders, knees under hips; arms fully lengthened, avoid locking elbows; chest and shoulders open, neck relaxed, tension-free. |

| Spinal alignment | Maintain accurate alignment by focusing on: (1) Sacrum: Base of the spine; (2) Thoracic spine: Mid-back between shoulder blades; (3) Back of the head: Neutral, no excessive tilt; and (4) Neutral lumbar spine: Avoid arching or flattening. |

| Activation and breathing | (1) Steady breathing: Controlled breathing throughout exercises; (2) Abdominal drawing-in maneuver: Gently tighten deep abdominals by drawing umbilicus to spine, engaging transversus abdominis; and (3) Posterior pelvic tilt: Rotate pelvis posteriorly. |

| Strength component | Isometric hold: Hold activated position (abdominal drawing-in maneuver + posterior pelvic tilt) for 5 seconds; focus on controlled contraction and relaxation. |

| Power component | Quick squeezes: Perform 10 rapid activations and relaxations of pelvic and abdominal muscles. |

| Endurance component | Sustained hold: Activate pelvic floor and deep abdominals to 50% of max effort; hold for 20+ seconds to build endurance. |

| Focus areas | (1) Core stability: Strengthens core and lumbo-pelvic hip complex stability; (2) Spinal alignment: Reduces lumbar strain, reinforces proper posture; (3) Pelvic floor activation: Enhances lumbar and pelvic support; and (4) Mindful breathing: Supports controlled activation and relaxation. |

| Purpose | Structured progression improves motor control, core stability, and lumbar-pelvic function, addressing chronic low back pain safely and effectively. |

| Position (P) | Starting position | Abdominal activation | Movement and repetitions |

| MAILE 4-point kneeling exercise (P1) | Hands and knees alignment: Shoulders at 90°, hands below shoulders. Hips and knees at 90°, neutral neck position. Open chest, relaxed shoulders, neutral spine (Figure 1A). | ADIM: Draw navel to spine. Slight posterior pelvic tilt. Engage transversus abdominis and pelvic floor while maintaining neutral spine. | Perform 10 reps per set, maintaining alignment and core activation for a few seconds. Complete 3 sets, with rest between. |

| Modified MAILE (50° hip flexion) (P2) | Hands and knees alignment: Shoulders at 90°, hands below shoulders. Hips at 50° flexion (hips slightly back), knees at 90°. Neutral neck, open chest, relaxed shoulders, neutral thoracic/lumbar spine (Figure 1B). | ADIM: Draw navel to spine. Slight posterior pelvic tilt. Engage transversus abdominis and pelvic floor while maintaining neutral lumbar spine. | Perform 10 reps per set, holding position for a few seconds. Complete 3 sets, resting appropriately between sets. |

| Modified MAILE (120° shoulder flexion) (P3) | Hands and knees alignment: Shoulders at 120°, hands slightly ahead of shoulders. Hips at 50° flexion (hips slightly back), knees at 90°. Neutral neck, open chest, relaxed shoulders, neutral thoracic/lumbar spine (Figure 1C). | ADIM: Draw navel to spine. Slight posterior pelvic tilt. Engage transversus abdominis, multifidus, and pelvic floor. Maintain neutral lumbar spine despite extended shoulder position. | Perform 10 reps per set, holding alignment for a few seconds per repetition. Complete 3 sets, taking rest between sets. |

| Modified MAILE (30° backward pelvic shift) (P4) | Hands and knees alignment: Shoulders at 120°, hands slightly ahead of shoulders. Hips at 50° flexion, knees at 90°. Neutral neck, open chest, relaxed shoulders, neutral thoracic/lumbar spine. Pelvis shifts 30° backward (Figure 1D). | ADIM: Draw navel to spine. Maintain slight posterior pelvic tilt while holding the shifted position. Engage transversus abdominis and pelvic floor without losing lumbar alignment. | Perform 10 reps per set, holding abdominal engagement during the backward shift for a few seconds. Complete 3 sets, with rest as needed. |

| Modified MAILE (halfway backward pelvic shift) (P5) | Hands and knees alignment: Shoulders at 120°, hands slightly ahead of shoulders. Hips at 50° flexion, knees at 90°. Neutral neck, open chest, relaxed shoulders, neutral thoracic/lumbar spine. Pelvis shifts halfway backward (Figure 1E). | ADIM: Draw navel to spine. Maintain posterior pelvic tilt and engage core muscles (transversus abdominis, pelvic floor). Keep lumbar spine neutral while shifting pelvis halfway. | Perform 10 reps per set, holding the halfway position with core engagement for a few seconds per repetition. Complete 3 sets, with appropriate rest. |

| Modified MAILE (maximum backward pelvic shift) (P6) | Hands and knees alignment: Shoulders at 120°, hands slightly ahead of shoulders. Hips at 50° flexion, knees at 90°. Neutral neck, open chest, relaxed shoulders, neutral thoracic/lumbar spine. Pelvis shifts maximally backward (Figure 1F). | ADIM: Draw navel to spine. Perform posterior pelvic tilt. Engage transversus abdominis, multifidus, and pelvic floor. Maintain spinal alignment and core engagement as the pelvis shifts back to its maximum extent. | Perform 10 reps per set, holding core engagement at maximum backward shift for a few seconds per repetition. Complete 3 sets, with rest between sets. |

The article selection process for this review focused on studies relevant to NCLBP and treatments involving core stability and lumbar-strengthening exercises. A systematic approach, which included database searches and predefined inclusion criteria, was employed to identify studies exploring the pathophysiology, epidemiology, and therapeutic interventions for NCLBP, with a particular emphasis on isometric exercises, core stability, and motor control. Collecting literature data involved a combination of primary and secondary data collection methods, each providing unique techniques for gathering and interpreting information. Primary data collection concentrates on acquiring new, firsthand data directly from sources. Common methods include surveys and questionnaires, which are structured tools designed to collect specific information from participants. These instruments are cost-effective, scalable, and suitable for large populations. Interviews offer another approach, where direct, in-depth questioning of individuals allows for detailed insights into complex topics. Observation, in contrast, involves watching and recording behaviors or events in their natural settings, providing contextual and real-time data. Experiments, which are controlled studies where variables are manipulated to observe their effects, are also an invaluable method for testing hypotheses. Secondary data was collected from published data. Methods in this category include document review, where researchers analyze existing documents such as articles, reports, and online content. Another common approach is using data from online databases, which assist researchers in finding relevant studies for analysis.

Several studies have highlighted the prevalence and impact of NCLBP globally and regionally, particularly in Saudi Arabia and Qatar, underscoring its significant burden in Middle Eastern countries[5-7]. Key studies focusing on core stability and lumbar muscle activation in managing NCLBP provide a foundation for exploring specific isometric exercise protocols, including MAILE[3,7-10]. These studies demonstrate that isometric exercises can effectively activate deep lumbar stabilizers, which are crucial for managing NCLBP. Additional research has provided therapeutic insights into muscle dysfunction and lumbar stability, which is essential for understanding the role of MAILE as an adjunct therapy[11]. Studies on spinopelvic alignment and muscle activation during therapeutic exercises support the need for targeted intervention[12]. These findings suggest that MAILE improves muscle activation patterns and enhances lumbar stability.

Combined with clinical reviews of stabilization and motor control exercises this work offers a comprehensive perspective on the role of motor control dysfunction and lumbar stability in NCLBP outcomes[13-15]. Some studies have also discussed the limitations and critiques of core stability concepts[16], presenting a balanced view of the potential contributions of MAILE. Evidence suggests that MAILE is a promising therapeutic approach for NCLBP, offering benefits such as pain reduction, enhanced muscle strength, and improved functional outcomes. Future research should focus on large-scale clinical trials to validate these findings and to inform clinical practice.

The current evidence on MAILE is limited by several significant methodological shortcomings, which undermine its reliability and generalizability. Many studies are small-scale, with insufficient sample sizes that reduce statistical power and limit the detection of significant effects. The lack of methodological rigor, such as the absence of proper blinding or randomization, introduces biases that may distort the reported outcomes. Additionally, most studies rely predominantly on subjective outcome measures, such as self-reported pain relief or functional improvement, which are vulnerable to reporting bias and individual variability. The underutilization of objective measures, such as electromyography for muscle activation analysis or motion analysis for biomechanical assessment, weakens the robustness of the evidence base. Heterogeneity in study protocols further complicates the evaluation of MAILE’s efficacy, with variations in frequency, intensity, and duration of interventions making it difficult to standardize clinical guidelines or draw consistent conclusions. Moreover, most studies feature short follow-up periods, failing to adequately assess the long-term benefits of MAILE or patient adherence to the intervention. Potential biases also compromise the strength of the evidence, including publication bias, where studies with positive findings are more likely to be published, creating an overly optimistic view of MAILE’s effectiveness. Conflicts of interest, such as funding from entities with vested interests in promoting MAILE, may influence study outcomes or interpretations. Still, these conflicts are often not transparently reported, diminishing the credibility of some findings. Furthermore, a significant limitation is the lack of direct comparisons between MAILE and well-established therapeutic interventions, such as core stabilization exercises, manual therapy, or dynamic lumbar strengthening programs. While MAILE shows promise, the absence of comparative data limits our understanding of its relative efficacy within the broader context of NCLBP management.

Lower back pain is often linked to vertebral misalignment[10], which alters the normal load distribution in the body during activities. Normal spinal curvatures from the neck to the pelvis help balance these loads. However, abnormal curvature or alignment (e.g., excessive lordosis) can place undue stress on the vertebral joints and intervertebral discs, potentially leading to nerve compression, disc degeneration, and inflammation[11,12]. Christie et al[13] have observed that patients with chronic LBP often present with increased lumbosacral angles, limited range of motion, lumbar flexion weakness, and imbalanced muscle strength[16]. Research has also highlighted that lumbar muscular atrophy and vertebral instability are strongly associated with chronic back pain[16]. Therefore, a key objective in treating chronic lumbar pain is to strengthen the lumbar muscles and improve flexibility[17]. Specifically, lumbar stabilization exercises have been shown to provide therapeutic benefits by promoting vertebral segment adjustment and enhancing lumbar muscle strength and dynamic stability[18-20].

Over the last four decades, research on trunk control has dramatically enhanced our understanding of neuromuscular reorganization following injury and in response to pain[21]. Studies on core stability have shown that injury and pain lead to changes in motor control, particularly in trunk muscles. These findings underscore the importance of retraining the motor control system to support spinal stability. However, the popularity of core stability training, particularly influenced by fitness trends such as Pilates, has led to some misunderstandings[21,22]. While it is commonly believed that strengthening the abdominal muscles is critical for back health, the true benefit lies in re-establishing motor control in the lumbar region. Staying active is key to improving clinical outcomes and mitigating the impact of back pain[23].

Stabilization exercise programs have become the mainstay of spinal rehabilitation, given their effectiveness in reducing pain and disability. These programs focus on improving core strength, restoring motor control, and enhancing lumbar stability. Although specific stabilization exercises have been shown to effectively reduce pain and disability in patients with chronic LBP, their efficacy for acute LBP is more limited. Despite this, stabilization exercises may play a crucial role in reducing recurrence rates in patients with acute LBP[24].

Although both MAILE and core stabilization exercises target lumbar muscle function and stability, the literature lacks direct comparisons of their outcomes. While stabilization exercises concentrate on retraining motor control and muscle function around the neutral zone of the spine, MAILE introduces a different approach through multi-angular isometric contractions that target the lumbar muscles at varying angles. Theoretically, this method allows for comprehensive muscle activation without dynamic movement, which can be particularly beneficial for patients with pain or instability.

No existing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have directly compared the clinical outcomes of MAILE with core stability exercises or lumbar stabilization exercises. This presents a crucial gap in the research, as comparative studies could provide valuable insights into which approach is more effective for pain relief, functional disability, and lumbar muscle strength in patients with chronic LBP. Given that both approaches aim to improve lumbar function and reduce pain, a comparative study would help identify the relative strengths of each method and inform clinical decision-making.

Effective literature data collection should rely on a blend of primary and secondary methods. Each method serves a specific purpose, contributing valuable insights and information. To ensure data validity, reliability, and accuracy, researchers must implement quality control measures, including standardized procedures, proper training and supervision, scientific sampling, and rigorous data validation. By adhering to these best practices, researchers can produce high-quality findings that contribute meaningfully to the advancement of knowledge.

Prioritize well-designed RCTs: Future studies should conduct large-scale RCTs that incorporate blinding and randomization to evaluate the efficacy and safety of MAILE rigorously. To clarify MAILE’s relative effectiveness, these trials should include direct comparisons with established treatments, such as core stabilization exercises, manual therapy, and dynamic lumbar strengthening programs.

Utilize objective outcome measures: To enhance reliability, research should include tools like electromyography to measure muscle activation, motion analysis to assess biomechanical improvements, and functional mobility tests. Long-term follow-up assessments are crucial to evaluating sustained outcomes and adherence.

Develop standardized intervention protocols: Establish uniform guidelines for MAILE, detailing exercise frequency, intensity, duration, and progression. Standardization will improve the consistency of results and facilitate clinical application.

Expand study populations: To increase generalizability, future research should examine MAILE’s effects in diverse patient populations, considering varying levels of disability, comorbidities, and chronicity of pain. This should include individuals with movement-related fear or instability.

Address methodological limitations: Mitigate issues observed in existing research by increasing sample sizes to improve statistical power, implementing longer follow-up periods, and reducing reliance on subjective self-reported outcomes.

Investigate mechanisms of action: To clarify its therapeutic mechanisms, research should delve into how MAILE influences motor control, lumbar stabilizer activation, and neuromuscular function.

Evaluate cost-effectiveness and accessibility: Studies should assess whether MAILE is cost-effective compared to other interventions and analyze its practical implementation, particularly in resource-limited settings or for patients requiring accessible treatment options.

Explore synergies with other therapies: Such as manual therapy or aerobic exercise, to maximize clinical outcomes. Future studies can provide robust evidence to validate MAILE’s clinical efficacy and guide its integration into standard practice for managing NCLBP.

NCLBP with motor control dysfunction significantly affects an individual’s quality of life and ability to perform daily activities. Traditional rehabilitation approaches often involve complex exercise routines or require equipment, making it difficult for patients to adhere to long-term programs. This clinical review aimed to assess the effectiveness of MAILE for treating NCLBP by focusing on the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex.

Motor control improvement: MAILE focuses on isolated activation of key muscles in the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex, facilitating better motor control and reducing strain on the affected structures.

Ease of implementation: Patients can perform this exercise anywhere and at any time without requiring specialized equipment.

Improving structural integrity: The MAILE approach reduces excessive lumbar movement and enhances pelvic alignment by addressing core and hip stability.

Accelerated recovery: Patients can return to normal daily functions quickly because the exercise is simple and effective in stabilizing the lumbopelvic region.

Reassurance for patients: One of the primary concerns for patients with NCLBP is the fear of permanent damage or serious underlying conditions. The MAILE program reassures patients that chronic LBP is benign and manageable. This intervention focuses on restoring proper movement patterns and motor control, thereby ensuring functional recovery. Patients should be encouraged to remain active and confident in their ability to return to daily life without the need for long-term therapy or advanced interventions.

Age Group: Adult patients ≤ 60 are more likely to experience significant improvements due to better adaptability and response to rehabilitation exercises such as MAILE.

Flexibility: Greater general flexibility. Specifically, patients with hamstring lengths greater than 90 degrees tend to respond well. This reflects better general flexibility and the ability to perform motor control exercises more effectively.

Prone instability test: A positive prone instability test indicates lumbar instability, which can be addressed through targeted exercises such as MAILE, which focuses on motor control and stabilization of the lumbopelvic hip complex.

Aberrant movement during spinal range of motion: Patients exhibiting aberrant movement patterns during the spinal range of motion, such as a painful arc of motion, abnormal lumbopelvic rhythm, or using arms on thighs for support, often indicate motor control issues that can benefit from structured activation and stabilization exercises in MAILE programs.

Postpartum women: The MAILE program may predict a good response in postpartum women. Postpartum patients often have specific pelvic and lumbar stability issues, and exercises targeting the lumbopelvic region can aid recovery by restoring motor control and muscle coordination.

Positive pelvic pain provocation tests: The positive posterior pelvic pain provocation (P4) test (thigh thrust test) highlights sacroiliac joint-related pain, which can be relieved through exercises that improve lumbopelvic stability, a primary focus of the MAILE program.

Positive active straight leg raises: This test indicates dysfunction in lumbopelvic control, where the MAILE program can be effective in strengthening core and hip stability.

Pain provocation with palpation: Positive pain provocation (lasting more than 5 seconds) after palpation of the posterior superior iliac spine region (long dorsal sacroiliac ligament).

Pubic symphysis: These points often indicate pelvic instability or dysfunction that can be addressed by MAILE exercises.

Trendelenburg sign: A positive Trendelenburg sign, indicating weakness in the hip abductor muscles, predicts the potential benefit of the MAILE program, which emphasizes strengthening and improving control of these muscles.

Lumbar spine load bearing and facet orientation: The lumbar spine is designed to bear heavy loads because it supports an upright posture. The lumbar facets are primarily oriented in the sagittal plane but transition to a more coronal orientation at the lumbosacral junction (L5-S1). This arrangement limits rotational flexibility while allowing greater mobility during flexion and extension. Lumbar facets carry approximately 18% of the axial load under normal conditions and up to 33% under extended postures, reflecting increased stress on these structures during certain movements. The facet joints and their articular capsules also provide up to 45% of the torsional strength of the lumbar spine, making them critical for stabilizing rotational forces.

Lumbar flexion: Lumbar flexion is controlled by eccentric contractions of the erector spinae muscles, while the psoas and abdominal muscles initiate flexion via concentric contractions. In the early stages of flexion (up to 60 degrees), the gluteus maximus and the hamstrings stabilize the pelvis. Beyond 60 degrees, these stabilizing forces diminish, allowing the pelvis to rotate an additional 30 degrees at the hip joints while the lumbar spine continues to flex (pelvic locking). Upon reaching full flexion, most muscles relax, except for the thoracic iliocostalis, which provides minimal support. In full flexion, the ligaments (such as the posterior longitudinal ligament, interspinal ligament, and posterior capsular ligaments) and passive muscle tension provide the necessary stability to the spine.

Flexion limitations: Lumbar flexion is limited by various ligamentous structures, including the ligamentum flavum, posterior longitudinal ligament, interspinal ligament, and posterior capsular ligament. These structures prevent excessive movement, which can lead to injuries.

Return to neutral position: Returning to the neutral spine position involves the pelvis moving first, under the control of the hip extensors. The erector spinae muscles then extend the lumbar spine, gradually controlling the return to an upright posture. This coordinated movement ensures stability and prevents excessive strain on the lower back.

Lumbar extension: Lumbar spine extension is initiated by concentric contraction of the erector spinae muscles. Once the initial movement is achieved, gravity and eccentric contraction of the abdominal muscles become the main forces controlling the extension.

Extension limitations: The anterior longitudinal ligament, anterior annulus, and bony impacts between the spinous processes and articular facets restrict the lumbar spine’s range of extension. These structures limit excessive backward bending and protect the spine from hyperextension injuries.

The MAILE program, which focuses on isolated activation and motor control of the lumbopelvic hip complex, leverages the lumbar spine’s natural movement patterns and kinetic limitations.

Controlled flexion and extension: The exercises should emphasize eccentric control during flexion and concentric activation during extension, ensuring proper engagement of the core and pelvic stabilizers.

Facet joint stability: Exercises are designed to avoid excessive rotation to protect the facet joints and capsules, particularly in patients with lumbar instability.

Pelvic and hip activation: Proper activation of the gluteus maximus and hamstrings during flexion and hip extensors during extension is critical for stabilizing the pelvis and ensuring smooth lumbar spine motion.

Ligament protection: Careful attention should be paid to avoid excessive flexion or extension that could stretch the ligaments of the lumbar spine, as these structures are critical in limiting unsafe movements. Finally, based on this review, we plan to conduct the first RCT comparing the MAILE technique to standard-of-care techniques in patients with NCLBP.

The MAILE approach targets key lumbar and abdominal muscles, including the erector spinae, multifidus, obliques, iliocostalis, longissimus spinalis, transversospinalis, rotatores brevis and longus, interspinalis, intertransversarii, rectus abdominis, quadratus lumborum, and psoas major. These muscles play a critical role in enhancing lumbar stability and motor control, making MAILE particularly relevant for managing NCLBP. MAILE presents a promising therapeutic intervention by directly addressing the muscular weaknesses and motor control dysfunctions commonly associated with this condition.

Adequate supervision during exercise sessions, along with clear instructions for participants to report any adverse events, is essential to ensure the intervention’s safety and success. The program’s low-impact, multi-angle isometric exercises specifically target deep lumbar stabilizers without the risks typically associated with dynamic movements, making it especially suitable for patients with NCLBP. Moreover, MAILE has shown potential in reducing pain, improving mobility, and enhancing lumbar stability, further supporting its integration into NCLBP management strategies - particularly in high-prevalence regions such as the Middle East.

Despite these encouraging findings, several methodological limitations must be addressed in future research. Current evidence, while promising, remains insufficient to draw definitive conclusions regarding MAILE’s long-term efficacy. To strengthen the evidence base, future studies should include larger, well-designed RCTs featuring appropriate blinding and randomization, standardized outcome measures, and extended follow-up periods. Including control groups and considering potential publication bias will also improve the validity of the findings. By addressing these limitations, future research can provide a more comprehensive understanding of MAILE’s therapeutic potential and its role in clinical practice, offering clearer guidelines for its widespread adoption in the management of NCLBP.

| 1. | Vrbanić TS. [Low back pain--from definition to diagnosis]. Reumatizam. 2011;58:105-107. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kent PM, Keating JL. The epidemiology of low back pain in primary care. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stilwell P, Harman K. Contemporary biopsychosocial exercise prescription for chronic low back pain: questioning core stability programs and considering context. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2017;61:6-17. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kim B, Yim J. Core Stability and Hip Exercises Improve Physical Function and Activity in Patients with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2020;251:193-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fleckenstein J, Floessel P, Engel T, Krempel L, Stoll J, Behrens M, Niederer D. Individualized Exercise in Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Exercise Alone or in Combination with Psychological Interventions on Pain and Disability. J Pain. 2022;23:1856-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Elnaggar RK, Elshazly FA, Elsayed WS, Ahmed AS. Determinants and relative risks of low back pain among the employees in Al-Kharj area, Saudi Arabia. Eur J Sci Res. 2015;135:299-308. |

| 7. | Bener A, Dafeeah EE, Alnaqbi K, Falah O, Aljuhaisi T, Sadeeq A, Khan S, Schlogl J. An epidemiologic analysis of low back pain in primary care: a hot humid country and global comparison. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4:220-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | França FR, Burke TN, Hanada ES, Marques AP. Segmental stabilization and muscular strengthening in chronic low back pain: a comparative study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:1013-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Panjabi MM. Clinical spinal instability and low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2003;13:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arokoski JP, Valta T, Kankaanpää M, Airaksinen O. Activation of lumbar paraspinal and abdominal muscles during therapeutic exercises in chronic low back pain patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:823-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rasmussen-Barr E, Nilsson-Wikmar L, Arvidsson I. Stabilizing training compared with manual treatment in sub-acute and chronic low-back pain. Man Ther. 2003;8:233-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Christie HJ, Kumar S, Warren SA. Postural aberrations in low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lederman E. The myth of core stability. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14:84-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Waddell G, Feder G, Lewis M. Systematic reviews of bed rest and advice to stay active for acute low back pain. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47:647-652. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Salik Sengul Y, Yilmaz A, Kirmizi M, Kahraman T, Kalemci O. Effects of stabilization exercises on disability, pain, and core stability in patients with non-specific low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Work. 2021;70:99-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elnaggar IM, Nordin M, Sheikhzadeh A, Parnianpour M, Kahanovitz N. Effects of spinal flexion and extension exercises on low-back pain and spinal mobility in chronic mechanical low-back pain patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16:967-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ergün T, Lakadamyalı H, Sahin MS. The relation between sagittal morphology of the lumbosacral spine and the degree of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2010;44:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moon HJ, Choi KH, Kim DH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Lee KH, Kim JH, Choi YJ. Effect of lumbar stabilization and dynamic lumbar strengthening exercises in patients with chronic low back pain. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37:110-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rajnics P, Templier A, Skalli W, Lavaste F, Illes T. The importance of spinopelvic parameters in patients with lumbar disc lesions. Int Orthop. 2002;26:104-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Faas A. Exercises: which ones are worth trying, for which patients, and when? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:2874-8; discussion 2878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Handa N, Yamamoto H, Tani T, Kawakami T, Takemasa R. The effect of trunk muscle exercises in patients over 40 years of age with chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sci. 2000;5:210-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Refshauge K. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:79-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Byström MG, Rasmussen-Barr E, Grooten WJ. Motor control exercises reduces pain and disability in chronic and recurrent low back pain: a meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:E350-E358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Akhtar MW, Karimi H, Gilani SA. Effectiveness of core stabilization exercises and routine exercise therapy in management of pain in chronic non-specific low back pain: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33:1002-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |