Published online Mar 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i3.103955

Revised: January 13, 2025

Accepted: February 18, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2025

Processing time: 97 Days and 10.5 Hours

Pedicle screw instrumentation is a critical technique in spinal surgery, offering effective stabilization for various spinal conditions. However, the impact of intraoperative imaging quality—specifically the use of both anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views—on surgical outcomes remains insufficiently studied. Eva

To evaluate how intraoperative imaging adequacy influences unplanned return-to-theatre rates, focusing on AP and lateral fluoroscopic views.

This retrospective cohort study analyzed 1335 patients who underwent thoracolumbar and sacral pedicle screw instrumentation between January 2013 and December 2022. Data on intraoperative imaging adequacy, screw placement, and URTT events were collected and statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS v23. Imaging adequacy was assessed based on the presence of both AP and lateral views, and outcomes were compared between imaging groups.

A total of 9016 pedicle screws were inserted, with 82 screws identified as mal

This study underscores that comprehensive intraoperative imaging with both AP and lateral views reduces unplanned returns, improves outcomes, enhances precision, and offers a cost-effective approach for better spinal surgery results.

Core Tip: This study underscores the importance of adequate intraoperative imaging in minimizing unplanned returns to theatre rates within 90 days after pedicle screw instrumentation. The findings reveal that using both anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic views significantly reduces the risk of revision surgeries caused by screw malplacement. This approach provides a practical, cost-effective method to enhance surgical precision, improve patient safety, and optimize resource utilization, particularly in healthcare settings with limited access to advanced imaging technologies.

- Citation: Sherif R, Spence EC, Smith J, McCarthy MJH. Intraoperative imaging adequacy and its impact on unplanned return-to-theatre rates in pedicle screw instrumentation. World J Orthop 2025; 16(3): 103955

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i3/103955.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i3.103955

Pedicle screws have become an integral part of spinal surgery, widely utilized for stabilizing and correcting deformities, as well as facilitating fusion[1-5]. Since their initial introduction in 1959[6], the technique has evolved significantly with advancements in imaging modalities, computer-assisted navigation, and robotic systems[7-10]. The posterior insertion of pedicle screws into the vertebral body provides a durable anchor, making them suitable for managing conditions such as fractures, tumors, infections, spondylolisthesis, and scoliosis[11]. While generally considered safe, pedicle screw insertion carries risks such as neurological, vascular, and visceral complications, with reported malplacement rates ranging from 1.7% to 35%[12-15]. Notably, malposition does not always necessitate revision and can often be asymptomatic[15].

Intraoperative imaging plays a pivotal role in ensuring pedicle screw placement accuracy. Computerized tomography (CT) is regarded as the "gold standard" for postoperative assessment due to its high precision, but its intraoperative use is limited by cost, radiation exposure, and logistical constraints[16-18]. Conventional fluoroscopy remains the most widely used modality intraoperatively, especially in resource-limited settings, offering the advantages of real-time guidance and lower costs. However, studies question its adequacy in reducing malplacement rates and subsequent unplanned returns to theatre (URTT) for revision surgeries[19,20]. Furthermore, emerging technologies, including 3D navigation systems and augmented reality-based approaches, have demonstrated potential in improving accuracy and reducing revision rates[21,22].

This study sought to quantitatively evaluate the influence of intraoperative imaging adequacy, specifically the acquisition and preservation of anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views using conventional fluoroscopy, on the incidence of URTT events. The cohort comprised adults undergoing pedicle screw instrumentation of the thoracic, lumbar, or first sacral vertebrae, irrespective of the underlying clinical indication. The null hypothesis tested was: “Inadequate intraoperative imaging does not increase the likelihood of unplanned return-to-theatre events within 90 days for pedicle screw revision or removal surgery”.

Within our institutions, pedicle screw placement is routinely performed using a "free-hand" technique, augmented by conventional fluoroscopy with a C-arm intensifier for intraoperative guidance. While this method represents the current standard of care, the extent to which the adequacy and documentation of intraoperative imaging influence clinical outcomes, particularly in relation to URTT rates due to screw malpositioning, remains underexplored. Emerging evidence suggests that adherence to enhanced imaging protocols and high-resolution standards could mitigate complications and reduce revision surgeries[23-25].

This study aims to bridge the existing knowledge gap by systematically analyzing the role of intraoperative imaging in optimizing surgical outcomes. By addressing this critical aspect of operative precision, the findings have the potential to inform the establishment of evidence-based imaging protocols, ultimately advancing patient safety, surgical efficacy, and cost-effectiveness in spinal instrumentation procedures.

A retrospective review of clinical data and imaging was conducted for all spinal operations performed at our hospitals between January 2013 and December 2022. Data were sourced from Bluespier for operative notes, Synapse Radiological Software (Fujifilm) for imaging, and Clinical Portal for written communications such as clinic letters and discharge summaries. The study focused on evaluating the impact of adequate intraoperative imaging, specifically AP and lateral views obtained via conventional fluoroscopy, on URTT rates within a 90-day period for pedicle screw revision or removal. While the 90-day window is a clinically relevant timeframe for capturing early complications, longer follow-up periods might reveal additional cases of screw malplacement that manifest beyond this window, particularly in asymptomatic patients or those with delayed-onset symptoms. Extending the follow-up duration could potentially provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between imaging adequacy and long-term surgical outcomes, further strengthening the findings and their implications for clinical practice.

A formal power analysis was not performed due to the retrospective design of the study and reliance on the available dataset of 1335 patients who met the inclusion criteria. However, the sample size is substantial, encompassing data from 6200 spinal operations, which provides a broad and representative basis for analysis. Given the relatively large cohort and the observed significant differences in URTT rates, the study findings are likely to be robust and reflective of clinical practice. Future prospective studies could incorporate power calculations to confirm and extend these findings.

The inclusion criteria were adults aged 18 years or older at the time of surgery who underwent thoracolumbar instrumentation with pedicle or medial cortical screws into the thoracic, lumbar, or first sacral vertebrae for any indication during the study period. Revision surgeries were included up to December 31, 2023, to allow for a minimum of 90 days of follow-up. Exclusion criteria included surgeries involving buck screws, pars screws, or instrumentation of cervical vertebrae, S2, or below, as well as patients under 18 years of age. The population was identified from a comprehensive list of spinal operations performed under consultant spinal surgeons.

The dataset included 6200 spinal operations, filtered to isolate 1335 patients who met the inclusion criteria. Duplicate entries and revision surgeries were consolidated under a single entry. Information collected included patient demographics, surgical indications, procedures performed, the type and number of screws inserted, intraoperative adverse events, and return-to-theatre events.

Radiological data were systematically reviewed to evaluate the adequacy and documentation of intraoperative and postoperative imaging, focusing on the presence and quality of AP and lateral views. Imaging was considered “adequate” if all screws and pedicles were clearly visualized from appropriate angles, enabling a thorough assessment of potential screw malplacement. Postoperative imaging performed more than three weeks after surgery was included to ensure a comprehensive dataset. Intraoperative imaging was conducted exclusively with conventional fluoroscopy using a C-arm image intensifier, adhering to established clinical practices.

The study employed several robust measures to minimize bias and enhance reliability. Blinding operative details, such as the surgeon’s identity and procedural specifics, mitigated potential confounding variables related to surgical experience or patient characteristics. Additionally, the independent review of radiological data by all authors further reduced subjective bias. The inclusion of AP and lateral projections aligns with standard intraoperative imaging protocols, but the criteria for determining adequacy could be more rigorously standardized to improve objectivity. Notably, interobserver reliability was ensured through consensus among authors, enhancing consistency in image evaluation and reducing variability. While these measures strengthen the study’s methodology, providing further details on patient selection and employing statistical controls for confounders would add depth to the analysis and improve the validity of the findings.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Software Version 25 to test the null hypothesis: "Inadequate intraoperative imaging does not lead to an increase in URTT events within 90 days for pedicle screw revision or removal surgery". Statistical significance was assessed to determine the relationship between imaging adequacy, screw malplacement, and URTT rates.

A total of 1335 patients met the inclusion criteria, with 9016 new pedicle screws inserted over the 10-year study period, excluding screws inserted during revision surgeries into existing tracts. Among these, 229 screws (2.5%) were midline cortical screws, with an average of 6.8 screws inserted per patient. Over the study period, 16% of patients (218 out of 1335) experienced at least one return to theatre. Based on surgical notes, intraoperative imaging, and postoperative imaging, 82 screws were identified as significantly malplaced in 52 patients (3.9%), with an average of 1.4 malplaced screws per affected patient. Of these patients, 46 (3.4%) required a return to theatre due to symptomatic screw malplacement, including 39 undergoing screw revision and 7 undergoing screw removal. Six patients with malplaced screws did not require surgical intervention.

Radiological data showed that 74 patients had no intraoperative imaging saved on Synapse, despite surgical notes in 23 cases indicating that imaging was performed. Among the remaining patients, 727 had both AP and lateral intraoperative imaging saved, of which 621 were deemed adequate, while 48 had AP imaging only, and 485 had lateral imaging only. Additionally, 118 cases involved reported adverse events. Of these, 52 were related to pedicle screws, such as the need to re-site a screw intraoperatively, while the remaining 67 were unrelated to the screws, such as dural tears or excessive blood loss.

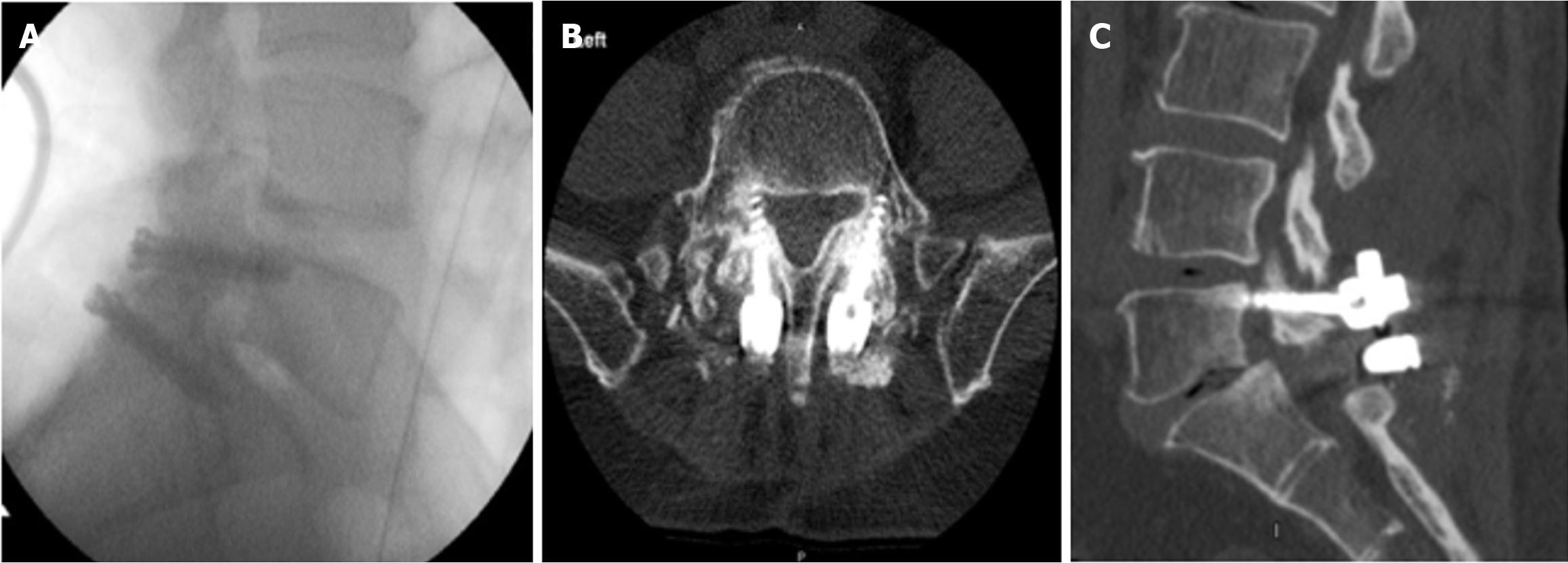

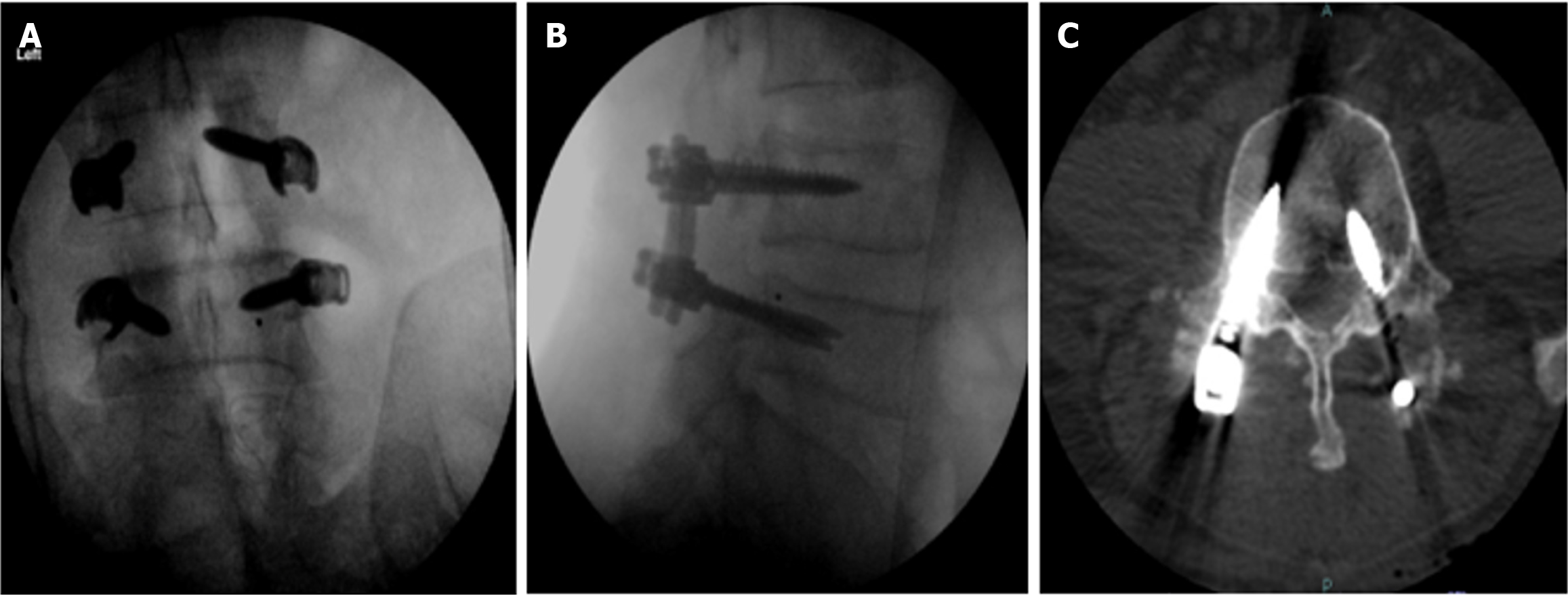

Within three months of surgery, 37 patients returned to theatre for the revision or removal of malplaced screws. Among these, 35% (13 out of 37) had both AP and lateral intraoperative imaging saved, (21 out of 37) had lateral imaging only, 2.7% (1 out of 37) had AP imaging only, and 5.4% (2 out of 37) had no imaging saved. In comparison, patients who did not return to theatre within 90 days due to malplacement showed a different distribution: 55.0% (714 out of 1298) had both AP and lateral imaging saved, 35.7% (464 out of 1298) had lateral imaging only, 3.6% (47 out of 1298) had AP imaging only, and 5.6% (73 out of 1298) had no imaging saved (Table 1). Figures 1 and 2 show examples of misplaced pedicle screws and midline cortical screws.

| Number of patients who returned within 90 days due to screw malplacement | Number of patients who did not return within 90 days for screw malplacement | Total | |

| AP and lateral intraoperative imaging saved | 13 | 714 | 727 |

| Only lateral intraoperative imaging saved | 21 | 464 | 485 |

| Only AP intraoperative imaging saved | 1 | 47 | 48 |

| No intraoperative imaging available | 2 | 73 | 75 |

| Total | 37 | 1298 | 1335 |

The likelihood of returning to theatre within three months due to screw malplacement was 1.8% when both AP and lateral imaging were taken and saved intraoperatively, 4.3% when only lateral imaging was taken, 2.08% when only AP imaging was taken, and 2.67% when no imaging was saved.

Statistical analysis using SPSS revealed that patients with both AP and lateral intraoperative imaging were significantly less likely to return to theatre within 90 days due to screw malplacement compared to those who did not have both imaging views (P = 0.017). Conversely, patients with only lateral imaging were more likely to return to theatre compared to those who did not receive only lateral imaging (P = 0.009). No significant associations were found for patients receiving only AP imaging (P = 0.767) or for those with no imaging saved (P = 0.955). These findings highlight the critical role of adequate intraoperative imaging in reducing the likelihood of symptomatic screw malplacement and subsequent revision surgeries.

This study demonstrates that the absence of both AP and lateral intraoperative imaging significantly increases the likelihood of return to theatre within three months due to symptomatic thoracolumbar screw malplacement. Notably, patients who received only lateral imaging exhibited the highest risk of revision surgery, reinforcing the critical role of comprehensive imaging during pedicle screw placement. These findings reject the null hypothesis, confirming that inadequate intraoperative imaging is associated with increased rates of URTT within 90 days for pedicle screw revision or removal surgery.

The results underscore the necessity for evidence-based guidelines advocating the routine use of both AP and lateral intraoperative imaging to optimize surgical outcomes and minimize revision rates. Despite the proven importance of adequate imaging, only 54.5% of patients in this study had both AP and lateral imaging saved, revealing significant variability in imaging practices within our hospitals. Standardization of intraoperative imaging protocols is imperative to reduce this inconsistency. The low overall rates of screw malplacement (3.9%) and intraoperative adverse events (5%) observed in this study align with previous literature[15,20,25], reaffirming that malplacement requiring revision surgery is relatively rare. Furthermore, six of the 52 patients with identified malplacements did not require revision surgery, supporting existing evidence that only severe malplacements necessitate surgical intervention[26].

Emerging technologies and techniques offer promising avenues to further mitigate risks associated with pedicle screw malplacement. Low-dose CT scans, for instance, could provide a viable alternative for postoperative imaging, balancing precision with reduced radiation exposure[27]. Similarly, ultrasound guidance has gained attention as a safer, radiation-free, and cost-effective intraoperative imaging modality[28]. Intraoperative CT navigation, while enhancing screw placement accuracy, has yet to show significant reductions in return-to-theatre rates[29]. Augmented reality systems represent another cutting-edge innovation, with recent studies reporting a screw placement accuracy rate of 98.2%, indicating their potential to revolutionize surgical precision[30]. Robotic-assisted systems are also gaining traction, offering reduced operating times and high accuracy rates, particularly benefiting less experienced surgeons. However, the steep learning curve and comparable outcomes to experienced surgeons using the "free-hand" technique suggest that robotics currently serve as an adjunct rather than a replacement for traditional methods[31].

Despite the study's robust findings, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The subjective definition of "adequate" imaging could introduce variability, particularly as data collection involved two different observers. While predefined imaging criteria and the study’s large sample size likely minimized interobserver bias, future studies could adopt more objective, standardized measures to further ensure reliability. Additionally, patient-specific factors such as spondy

This study contributes to the growing body of evidence highlighting the importance of adequate intraoperative imaging in reducing the risk of symptomatic malplacement and revision surgery. It also identifies areas for improvement in clinical practice, emphasizing the need for standardized imaging protocols. The findings support ongoing research into innovative imaging technologies, including low-dose CT, ultrasound, augmented reality, and robotic systems, to enhance surgical precision and minimize adverse outcomes. Future investigations should focus on evaluating the long-term benefits of these advancements and their integration into routine surgical workflows to optimize patient outcomes and reduce healthcare costs.

This study demonstrates that inadequate intraoperative imaging significantly increases URTT rates within 90 days following pedicle screw instrumentation, validating the hypothesis and emphasizing the importance of standardized imaging protocols. The combined use of AP and lateral fluoroscopic views is essential in reducing revision surgeries, offering a cost-effective and accessible alternative to advanced imaging technologies. These findings support the adoption of evidence-based imaging standards to enhance surgical precision, improve patient outcomes, and optimize healthcare resource utilization.

I would like to thank John Howes, Sashin Ahuja, Iqroop Chopra, Stuart James, Alwyn Jones, Francis Brooks, Alexander Durst, Khaled Badran, Savithru Prakash, Ahmed Sherif for their extraordinary support in this research project.

| 1. | Boon Tow BP, Yue WM, Srivastava A, Lai JM, Guo CM, Wearn Peng BC, Chen JL, Yew AK, Seng C, Tan SB. Does Navigation Improve Accuracy of Placement of Pedicle Screws in Single-level Lumbar Degenerative Spondylolisthesis?: A Comparison Between Free-hand and Three-dimensional O-Arm Navigation Techniques. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28:E472-E477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Luther N, Iorgulescu JB, Geannette C, Gebhard H, Saleh T, Tsiouris AJ, Härtl R. Comparison of navigated versus non-navigated pedicle screw placement in 260 patients and 1434 screws: screw accuracy, screw size, and the complexity of surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28:E298-E303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Borcek AO, Suner HI, Emmez H, Kaymaz M, Aykol S, Pasaoglu A. Accuracy of pedicle screw placement in thoracolumbar spine with conventional open technique. Turk Neurosurg. 2014;24:398-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Carbone JJ, Tortolani PJ, Quartararo LG. Fluoroscopically assisted pedicle screw fixation for thoracic and thoracolumbar injuries: technique and short-term complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gaines RW Jr. The use of pedicle-screw internal fixation for the operative treatment of spinal disorders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1458-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boucher HH. A method of spinal fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1959;41-B:248-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Conrads N, Grunz JP, Huflage H, Luetkens KS, Feldle P, Grunz K, Köhler S, Westermaier T. Accuracy of pedicle screw placement using neuronavigation based on intraoperative 3D rotational fluoroscopy in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143:3007-3013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ueno J, Torii Y, Umehra T, Iinuma M, Yoshida A, Tomochika K, Niki H, Akazawa T. Robotics is useful for less-experienced surgeons in spinal deformity surgery. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2023;33:1805-1810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Torii Y, Ueno J, Iinuma M, Yoshida A, Niki H, Akazawa T. Accuracy of robotic-assisted pedicle screw placement comparing junior surgeons with expert surgeons: Can junior surgeons place pedicle screws as accurately as expert surgeons? J Orthop Sci. 2023;28:961-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Newell R, Esfandiari H, Anglin C, Bernard R, Street J, Hodgson AJ. An intraoperative fluoroscopic method to accurately measure the post-implantation position of pedicle screws. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2018;13:1257-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boos N, Webb JK. Pedicle screw fixation in spinal disorders: a European view. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:2-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Parker SL, Amin AG, Santiago-Dieppa D, Liauw JA, Bydon A, Sciubba DM, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL, Witham TF. Incidence and clinical significance of vascular encroachment resulting from freehand placement of pedicle screws in the thoracic and lumbar spine: analysis of 6816 consecutive screws. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:683-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mattei TA, Meneses MS, Milano JB, Ramina R. "Free-hand" technique for thoracolumbar pedicle screw instrumentation: critical appraisal of current "state-of-art". Neurol India. 2009;57:715-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tang J, Zhu Z, Sui T, Kong D, Cao X. Position and complications of pedicle screw insertion with or without image-navigation techniques in the thoracolumbar spine: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Biomed Res. 2014;28:228-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chong XL, Kumar A, Yang EWR, Kaliya-Perumal AK, Oh JY. Incidence of pedicle breach following open and minimally invasive spinal instrumentation: A postoperative CT analysis of 513 pedicle screws applied under fluoroscopic guidance. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2020;10:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kosmopoulos V, Theumann N, Binaghi S, Schizas C. Observer reliability in evaluating pedicle screw placement using computed tomography. Int Orthop. 2007;31:531-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sarwahi V, Suggs W, Wollowick AL, Kulkarni PM, Lo Y, Amaral TD, Thornhill B. Pedicle screws adjacent to the great vessels or viscera: a study of 2132 pedicle screws in pediatric spine deformity. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2014;27:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Piazzolla A, Montemurro V, Bizzoca D, Parato C, Carlucci S, Moretti B. Accuracy of plain radiographs to identify wrong positioned free hand pedicle screw in the deformed spine. J Neurosurg Sci. 2019;63:372-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yanni DS, Ozgur BM, Louis RG, Shekhtman Y, Iyer RR, Boddapati V, Iyer A, Patel PD, Jani R, Cummock M, Herur-Raman A, Dang P, Goldstein IM, Brant-Zawadzki M, Steineke T, Lenke LG. Real-time navigation guidance with intraoperative CT imaging for pedicle screw placement using an augmented reality head-mounted display: a proof-of-concept study. Neurosurg Focus. 2021;51:E11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Balling H, Blattert TR. Rate and mode of screw misplacements after 3D-fluoroscopy navigation-assisted insertion and 3D-imaging control of 1547 pedicle screws in spinal levels T10-S1 related to vertebrae and spinal sections. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:2898-2905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Afzali M, Shojaie P, Iyengar KP, Nischal N, Botchu R. Intraoperative Radiological Imaging: An Update on Modalities in Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery. J Arthrosc Jt Surg. 2023;10:54-61. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Kalidindi KKV, Sharma JK, Jagadeesh NH, Sath S, Chhabra HS. Robotic spine surgery: a review of the present status. J Med Eng Technol. 2020;44:431-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Van de Kelft E, Costa F, Van der Planken D, Schils F. A prospective multicenter registry on the accuracy of pedicle screw placement in the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral levels with the use of the O-arm imaging system and StealthStation Navigation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:E1580-E1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang MY, Kim KA, Liu CY, Kim P, Apuzzo ML. Reliability of three-dimensional fluoroscopy for detecting pedicle screw violations in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:1138-42; discussion 1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tian NF, Xu HZ. Image-guided pedicle screw insertion accuracy: a meta-analysis. Int Orthop. 2009;33:895-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hicks JM, Singla A, Shen FH, Arlet V. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in scoliosis surgery: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E465-E470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Abul-Kasim K, Strömbeck A, Ohlin A, Maly P, Sundgren PC. Reliability of low-radiation dose CT in the assessment of screw placement after posterior scoliosis surgery, evaluated with a new grading system. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:941-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Patel MR, Jacob KC, Parsons AW, Chavez FA, Ribot MA, Munim MA, Vanjani NN, Pawlowski H, Prabhu MC, Singh K. Systematic Review: Applications of Intraoperative Ultrasonography in Spinal Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2022;164:e45-e58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | La Rocca G, Mazzucchi E, Pignotti F, Nasto LA, Galieri G, Olivi A, De Santis V, Rinaldi P, Pola E, Sabatino G. Intraoperative CT-guided navigation versus fluoroscopy for percutaneous pedicle screw placement in 192 patients: a comparative analysis. J Orthop Traumatol. 2022;23:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bhatt FR, Orosz LD, Tewari A, Boyd D, Roy R, Good CR, Schuler TC, Haines CM, Jazini E. Augmented Reality-Assisted Spine Surgery: An Early Experience Demonstrating Safety and Accuracy with 218 Screws. Global Spine J. 2023;13:2047-2052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fatima N, Massaad E, Hadzipasic M, Shankar GM, Shin JH. Safety and accuracy of robot-assisted placement of pedicle screws compared to conventional free-hand technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2021;21:181-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |