Published online Mar 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i3.101841

Revised: February 10, 2025

Accepted: February 17, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2025

Processing time: 164 Days and 21.4 Hours

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is vital for regulating posterior tibial translation in relation to the femur, which is critical for knee stability. PCL tears are infrequently isolated in knee injuries; however, the absence of the PCL results in abnormal knee kinematics, which may cause injuries to other ligaments. The ideal tendon source for PCL reconstruction is still a subject of debate.

To evaluate the results of employing the peroneus longus tendon (PLT) in PCL reconstruction.

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify relevant randomized controlled trials and retrospective observational studies discussing the outcomes of using the PLT for PCL reconstruction. Studies published up to August 2024 were searched across multiple databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. Full texts of the selected articles were retrieved, reviewed, and independently assessed by the investigators. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, with any remaining disagreements being arbitrated by a third author.

This meta-analysis included five studies on PLT use for PCL reconstruction: (1) Four prospective studies with 104 patients; and (2) One retrospective study with 18 patients. Most studies followed up participants for 24 months, while one had a shorter follow-up of 18 months. Lysholm and modified cincinnati scores improved by pooled means of 32.2 (95%CI: 29.3-35.1, I2 = 0%) and 31.1 (95%CI: 27.98-34.22, I2 = 0%), respectively. Postoperative American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society and Foot and Ankle Disability Index scores were 94.5 (I2 = 61.5%) and 94.5 (I2 = 80.09%), respectively. Single-hop and triple-hop test scores averaged 95.5 (95%CI: 94.5-96.5) and 92.4 (95%CI: 91.9-92.9) respectively. No significant differences were observed in thigh circumference at 10 cm and 20 cm between the injured and healthy sides.

Evidence supports PLT autografts for PCL reconstruction, improving knee function and patient outcomes. Larger randomized trials are needed to confirm efficacy and compare graft options.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis demonstrates that the peroneus longus tendon autograft is a viable and effective option for posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, with evidence supporting improved knee stability and functional outcomes. Favourable muscle preservation is a key advantage. However, further high-quality studies are needed to confirm its long-term efficacy and safety across diverse populations.

- Citation: Yousif Mohamed AM, Salih M, Mohamed M, Abbas AE, Elsiddig M, Abdelsalam M, Elhag B, Mohamed N, Ahmed S, Omar D, Ahmed S, Mohamed D. Functional outcomes of peroneus longus tendon autograft for posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A meta-analysis. World J Orthop 2025; 16(3): 101841

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i3/101841.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i3.101841

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) serves as the primary posterior stabilizer during flexion and is the largest and most robust ligament in the human knee[1]. It is roughly twice as strong as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Thus, the ACL is more prone to rupture than the PCL[2,3]. Isolated PCL rupture is rare in instances of knee injury. Nonetheless, the absence of the PCL will result in abnormal knee kinematics, consequently causing injuries to other knee ligaments[4].

PCL injuries occur due to posteriorly directed force on the proximal tibia during knee flexion. Injuries incurred from dashboard impacts during vehicular collisions are a common cause of PCL tears. The PCL may sustain injury due to a fall, leading to forceful impact on the proximal leg with a flexed knee. PCL injuries are commonly incurred in sports including football, skiing, soccer, and baseball. Rotational hyperextension injuries can lead to PCL tears[5,6].

Various graft options exist for PCL reconstruction, encompassing autografts and allografts. Allografts are the most commonly utilized graft option for PCL reconstruction, providing sufficient graft strength while reducing donor site morbidity. Moreover, they require smaller incisions and have been shown to decrease operative time[7].

Surgeons have several options for potential grafts, including the bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB), quadriceps tendon, and hamstring tendon (HT) graft[8]. Nonetheless, each of these grafts presents distinct challenges. Bone-to-bone healing is enhanced by BPTB, allowing for a swifter resumption of physical activity compared to alternative grafts. Nonetheless, BPTB may lead to anterior knee pain, discomfort while kneeling, tenderness over bone defects, patellar fractures, a compromised extensor mechanism, and the possibility of a shortened graft length for PCL replacement. The HT autograft addresses these deficiencies of BPTB. The HT autograft is readily obtainable, possesses a large surface area that facilitates revascularization post-implantation, and provides adequate graft length. Furthermore, it possesses exceptional tensile strength[9]. Hamstring autografts may have drawbacks, including a significant risk of saphenous nerve injury, thigh hypotrophy, and discomfort in the hamstring area[10,11].

This meta-analysis is the first study to systematically evaluate the efficacy and outcomes of this method. This analysis synthesizes data from multiple studies to provide an overview of the clinical outcomes linked to the application of peroneus longus tendon (PLT) in PCL reconstruction.

This study conducted a meta-analysis following the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines[12] and was registered under PROSPERO number CRD42024584811.

The PICOT algorithm was applied as follows. The population (P) consisted of patients with PCL tears. The intervention (I) involved primary isolated PCL reconstruction. The comparison (C) was made using PLT autografts. The outcomes (O) focused on two aspects: (1) Knee functional outcomes, which included scores such as the Lysholm Knee Score, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, and Cincinnati score; and (2) Functional outcomes of the graft-donor ankle, measured using the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score and Foot and Ankle Disability Index (FADI) score. Alongside the postoperative single-hop test score, triple-hop test score, and postoperative thigh circumferences measured at 10 cm and 20 cm. The follow-up duration (T) was at least 18 months.

The first author independently performed the literature search in August 2024. The PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science Cochrane Library and Google database All were examined irrespective of location or publication type. This search utilized no filters. The subsequent keywords were utilized in conjunction: (1) Posterior cruciate ligament; (2) PCL; (3) Reconstruction; (4) Peroneus longus tendon; (5) PLT; (6) Clinical outcome; (7) PROMs; and (8) Patient-reported outcome measures.

This study examined relevant research involving adult humans within the reference lists of associated reviews and original articles. All language studies were taken into account. Since the data for this meta-analysis originated from published articles, ethical approval was not required.

All prospective and retrospective studies that included patients with isolated PCL injuries, whether acute or chronic, without any prior history of ligamentous injury and treated with autologous PLT graft, were deemed eligible for inclusion. Only studies with a follow-up duration of no less than 18 months were included.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) Involved alternative graft modalities; (2) Included fractures in the knee region; (3) Addressed pathological conditions in the lower extremity; (4) Lacked quantitative data; (5) Employed supplementary tendons, such as HTs, alongside the peroneus tendon; (6) Incorporated treatments like platelet-rich plasma; and (7) Utilized adjustable-loop femoral cortical suspension. Additionally, technical notes, abstracts, editorials, comments, letters, case reports, case series, and articles based on cadaveric studies were not accepted.

Five authors independently selected data for this study. Initially, all article titles were meticulously examined, and those relevant to the research topic were chosen for additional review. The complete text was obtained if the title aligned with the study objectives. The first author's contributions were employed to rectify any inconsistencies. All articles that lacked full-text accessibility were excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, relevant articles were identified through the manual screening of bibliographies. All articles identified through these processes were assessed, and their eligibility was discussed among the researchers. Careful consideration and consensus among the reviewers were employed to resolve discrepancies and disagreements.

Data extraction was conducted independently by four authors. Initially, data were obtained using a pre-prepared Excel form. Two authors then cross-checked the data, and any discrepancies were resolved by the first author. Author, year of publication, country, study design, number of cases, patient characteristics (mean age and sex), length of follow-up and conclusion were among the information that was retrieved. Additionally, functional outcomes including Tegner Lysholm Knee Score, IKDC score, Cincinnati score, AOFAS score and FADI score were recorded. In addition to postoperative single-hop test score, triple-hop test score, and postoperative thigh circumferences at 10 cm and 20 cm.

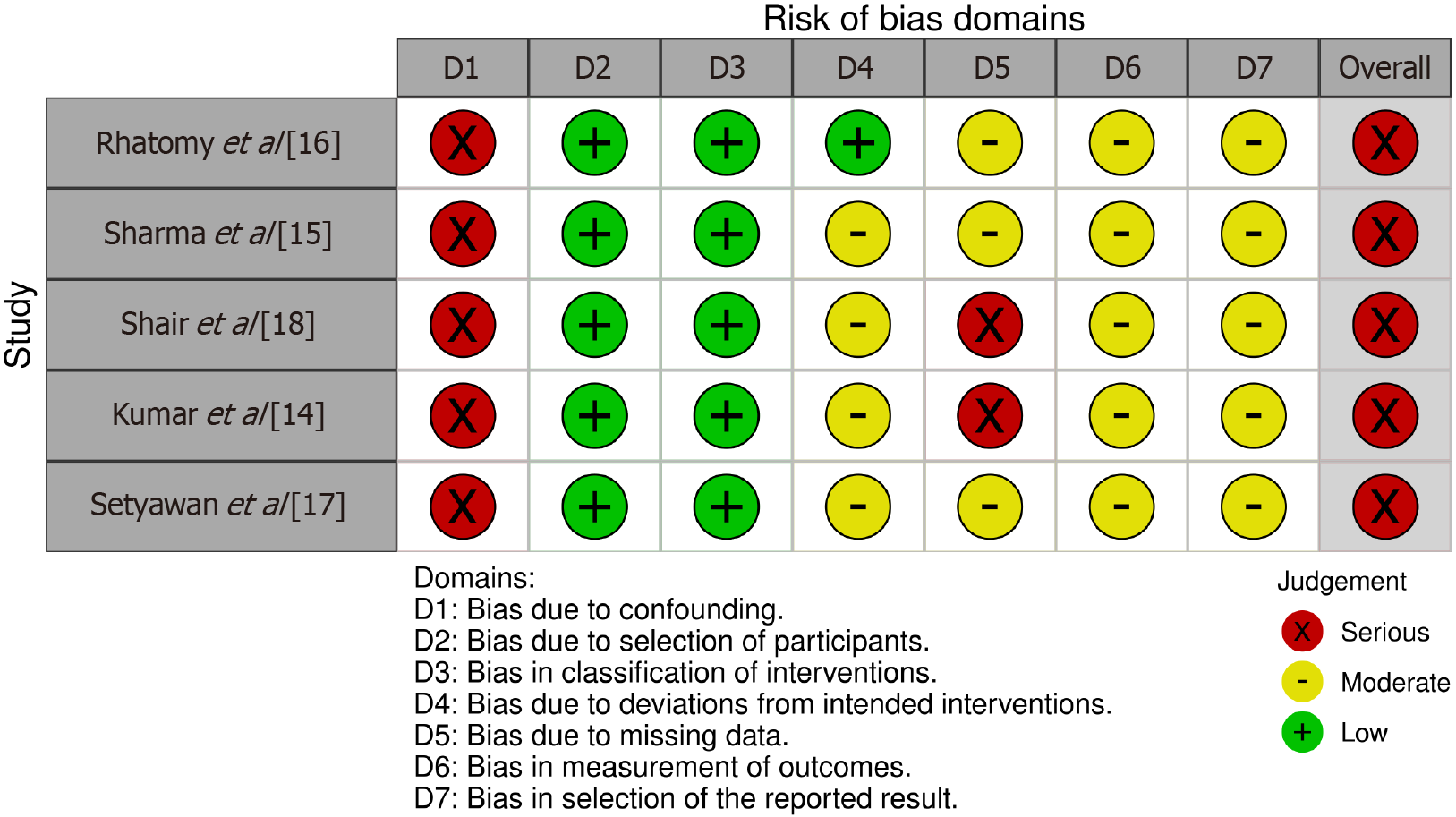

A risk of bias assessment using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions tool[13] for non-randomized clinical trials was performed on the following five studies: (1) Kumar et al[14]; (2) Sharma et al[15]; (3) Rhatomy et al[16]; (4) Setyawan et al[17]; and (5) Shair et al[18] (Figure 1). All studies showed a moderate risk of bias due to missing data (D5), except for Kumar et al[14] which had a serious risk. Similarly, all studies displayed a serious risk of bias from confounding (D1). A moderate risk of bias was consistently observed for outcome measurement (D6) and selection of reported results (D7). Conversely, all studies consistently exhibited a low risk of bias in participant selection (D2) and intervention classification (D3). Ultimately, all studies demonstrated a moderate risk of bias in deviations from intended interventions (D4), except Rhatomy et al[16] which showed a low risk of bias.

The study conducted by Faisal et al[19] was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale[20]. It indicated a "fair quality" rating. The study was awarded one star in the Selection domain for its clear definition of the exposure and another star for demonstrating the absence of the outcome of interest at baseline. Nevertheless, it was not awarded a star for the representativeness of the exposed cohort. Furthermore, the 'Selection of the non-exposed cohort' domain was not applicable in this case, as it was not a comparative study. The Comparability domain was not awarded any stars as a result of the absence of a comparison group and the absence of control for confounders. The study received three stars in the Outcome domain for the following reasons: (1) The use of validated outcome measures; (2) The completion of all follow-ups; and (3) The adequate duration of the follow-up of all participants.

The single-arm meta-analysis utilized OpenMeta Software (version 12.11.14), whereas the double-arm meta-analysis for thigh circumference at 10 cm and 20 cm outcomes used RevMan software (version 5.4). For the single-arm meta-analysis, we calculated pooled means and 95%CI for changes from baseline in the outcomes of IKDC, Lysholm, and modified cincinnati score, as well as postoperative AOFAS score, postoperative FADI score, postoperative single-hop test score, and postoperative triple-hop test score outcomes. The double-arm meta-analysis involved pooling the extracted data as mean differences (MDs) along with their corresponding 95%CI. The assessment of heterogeneity was conducted using I2, where values exceeding 50% are interpreted as indicative of substantial heterogeneity, in alignment with the guidelines specified in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions[21]. For analyses exhibiting significant heterogeneity, we employed a random-effects model, while a fixed-effects model was utilized in other cases.

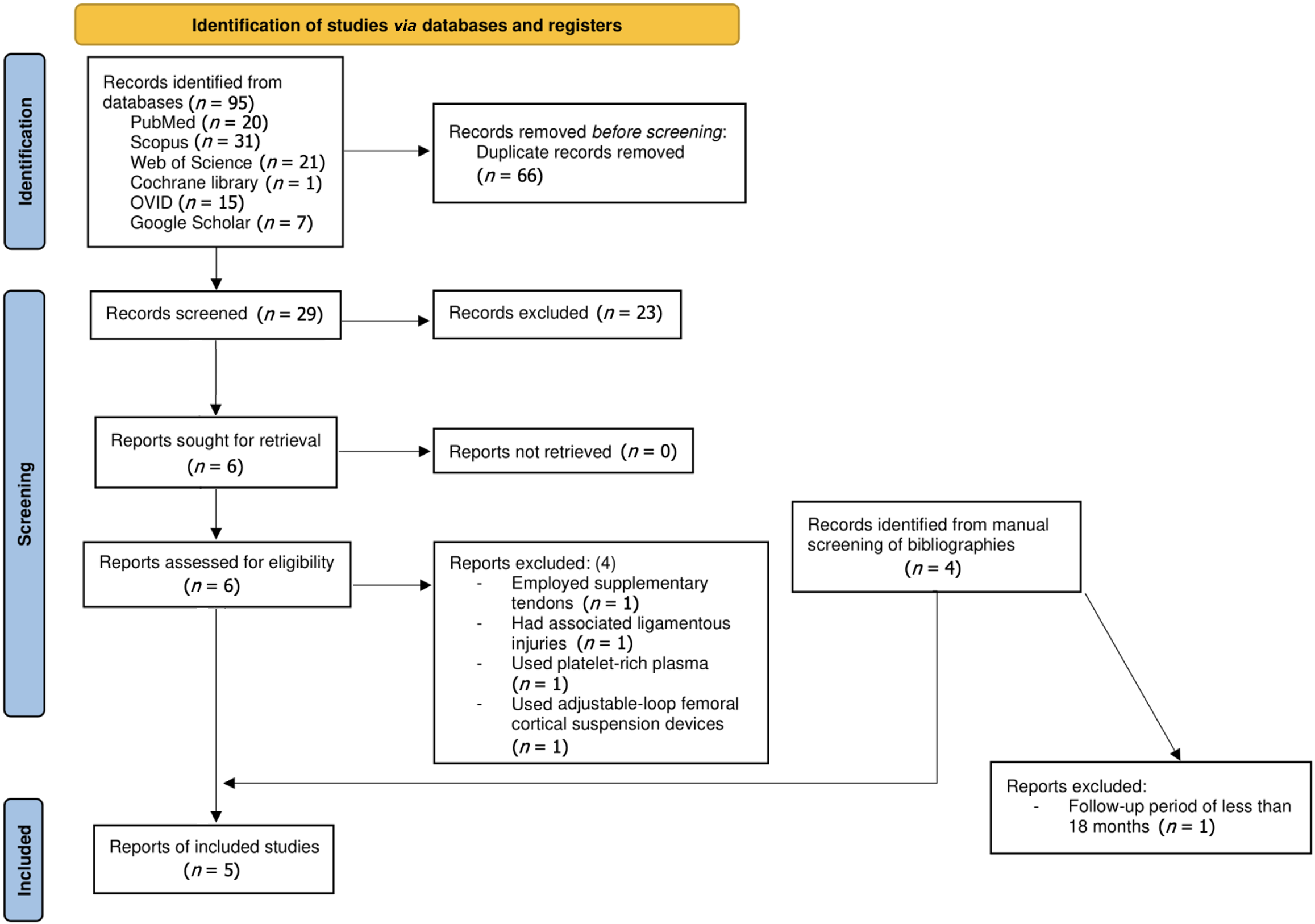

A comprehensive computerized search utilized multiple databases and resulted in a total of 95 studies. This search incorporated notable sources such as Scopus (n = 31), Web of Science (n = 21), PubMed (n = 20), OVID (n = 15), Google Scholar (n = 7), and Cochrane Library (n = 1). Following the elimination of 66 duplicates, 29 publications persisted. Subsequent to the screening of titles and abstracts, six studies were chosen for comprehensive evaluation. Among these, a particular study[22] utilized supplementary tendons, one study employed platelet-rich plasma[23], and one study utilized adjustable-loop femoral cortical suspension devices[24], one study had associated ligamentous injuries[25], all of which were excluded. Ultimately, two studies met all eligibility criteria. Additionally, four studies were identified through other sources, with one study[18] excluded due to a follow-up of less than 18 months, resulting in a total of five studies[14-17,19] included in the final analysis. The details of the selection method are summarized in a flow chart (Figure 2).

This review included five studies (Table 1) that utilized the PLT for PCL reconstruction[14-17,19]. Of the studies identified, four were prospective[14-17] with a total of 104 patients, and one was retrospective[19] with a total of 18 patients. All research was performed from 2014 to 2023. Two studies were performed in India, two in Indonesia, and one in Bangladesh. The gender distribution showed a higher prevalence of male participants, with all studies having more male than female cases. The average age of participants varied between 25.86 and 32 years, although one study[15] did not disclose the mean age. The follow-up periods in the studies also varied, with most studies[14,16,17,19] following up with participants for 24 months. One study[15] had a shorter follow-up period of 18 months.

| Ref. | Country | Study period | Study design | Patients (n) | Male/female | Mean age (years) | Follow-up (months) | Conclusion |

| Kumar et al[14], 2023 | India | N/M | Prospective study | 24 | 24/0 | 29.5 | 24 | Arthroscopic single bundle PCL reconstruction using ipsilateral peroneus longus tendon autograft had significant improvement in functional outcome of the knee based on IKDC and Tegner Lysholm score. Ankle function was also found to be preserved based on Foot and Ankle Disability Index score at 2-years follow-up |

| Sharma et al[15], 2023 | India | August 2019 to July 2020 | Prospective study | 12 | 9/3 | N/M | 18 | Single bundle PCL reconstruction with peroneus long us tendon auto graft had improvement functional outcome (IKDC, modified cincinnati, Lysholm) and shown excellent ankle function and serial hop test result at 18 months evaluation |

| Faisal et al[19], 2022 | Bangladesh | January 2018 and December 2019 | Retrospective study | 18 | 16/2 | 32 | 24 | Peroneus longus tendon autograft used in PCL reconstruction had improved functional outcome (IKDC, Lysholm) and shown excellent ankle function and serial hop test result at two-year evaluation and can be encouraged as a graft of choice |

| Rhatomy et al[16], 2021 | Indonesia | 2014 and 2017 | Prospective study | 28 | 22/6 | 29.1 | 24 | Peroneus longus tendon is a good choice as a graft in PCL reconstruction at the 2-year follow-up, with minimal donor site morbidity |

| Setyawan et al[17], 2019 | Indonesia | October 2015 and June 2016 | Prospective cohort study | 15 | 11/4 | 25.86 | 24 | Single bundle PCL reconstruction with peroneus longus tendon autograft had improvement functional outcome (IKDC, modified cincinnati, Lysholm) and shown excellent ankle function and serial hop test result at two-years evaluation |

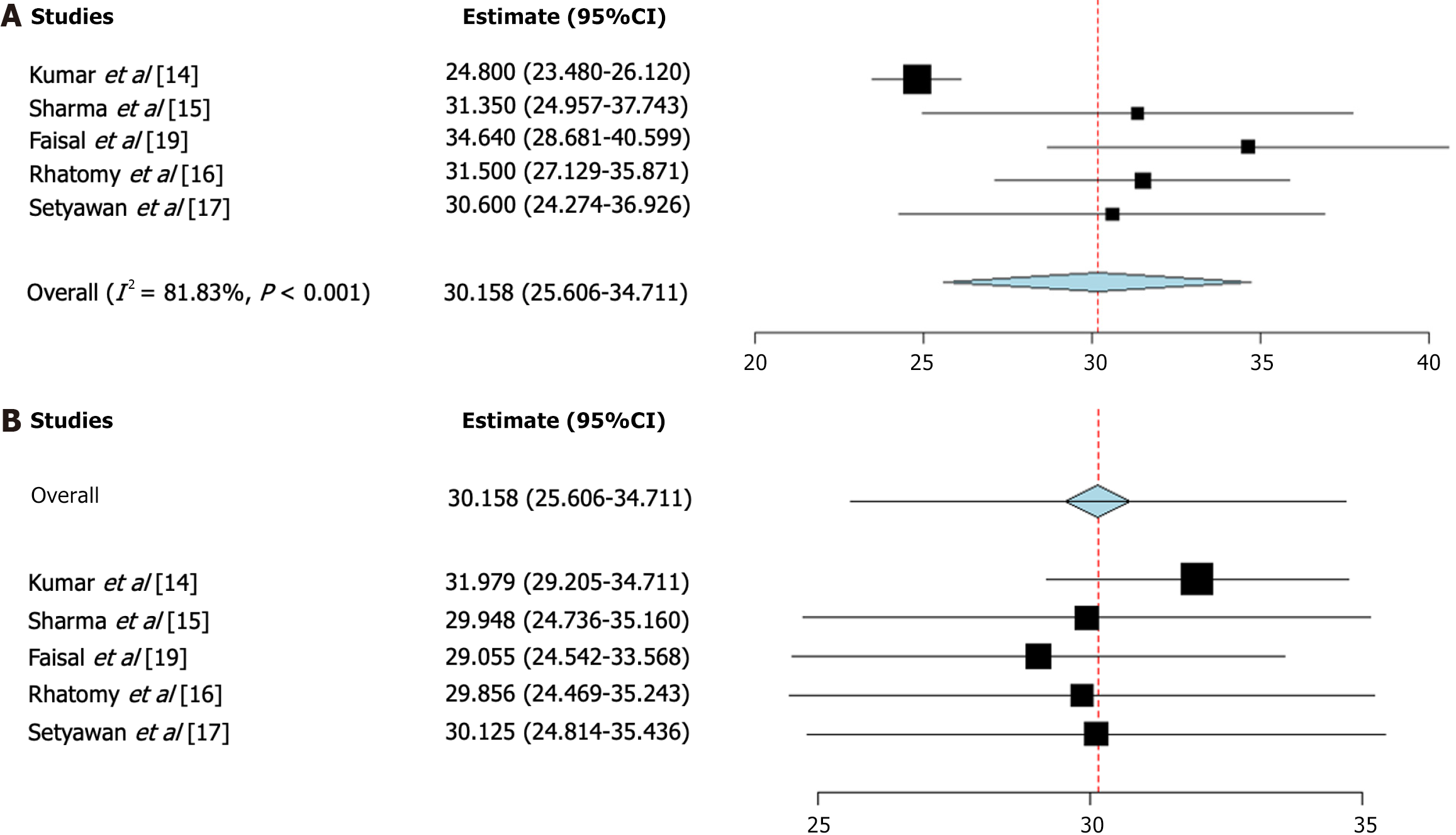

IKDC score change: IKDC scores change after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported by five studies[14-17,19]. The pooled mean of IKDC score change was 31.2 with a 95%CI: 25.6-34.7. The pooled studies were heterogeneous

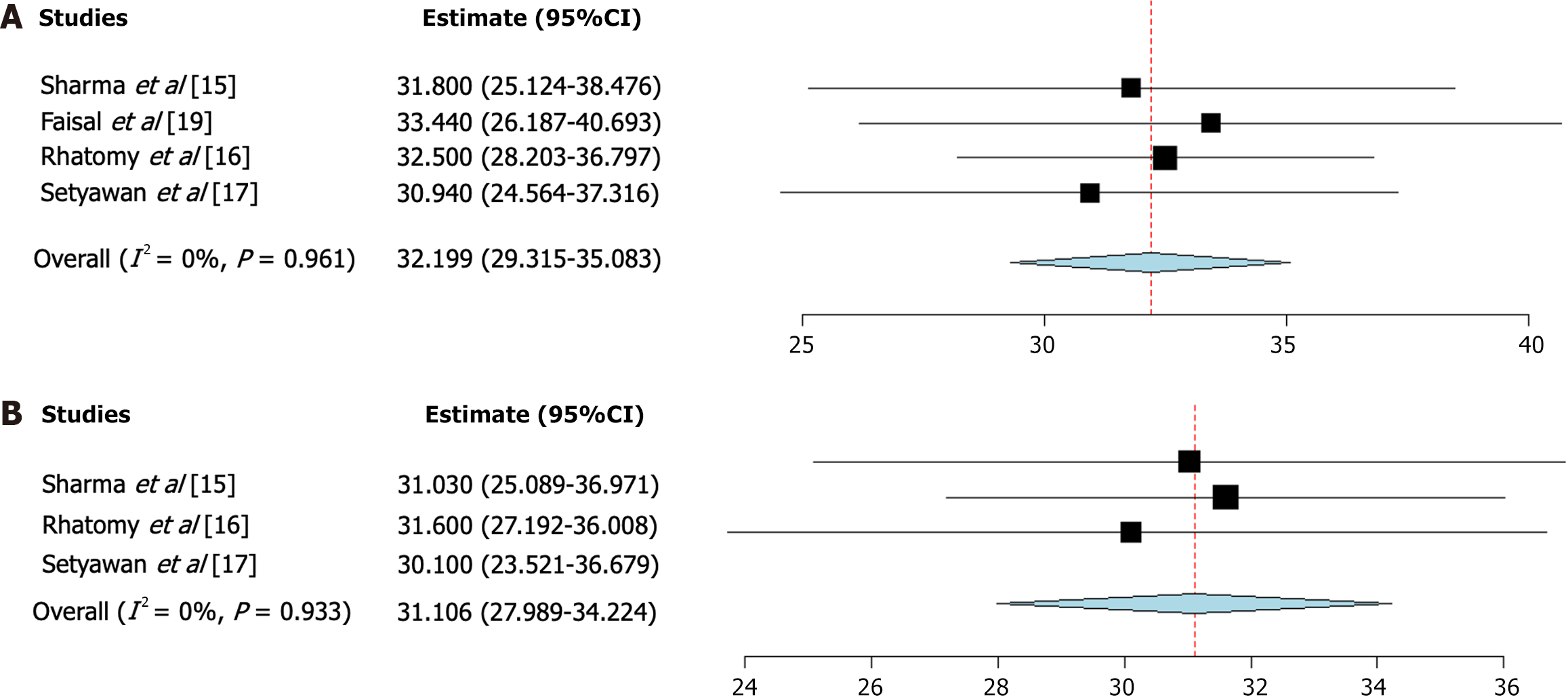

Lysholm Score change: Lysholm Score changes after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported by four studies[15-17,19]. The pooled mean of Lysholm Score change was 32.2 with a 95%CI: 29.3-35.1. The pooled studies were homogenous (I2 = 0%, P value = 0.96) (Figure 4A)[15-17,19].

Modified cincinnati score change: Modified cincinnati scores change after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported by three studies[15-17]. The pooled mean of modified cincinnati score change was 31.1 with a 95%CI: 27.98-34.22. The pooled studies were homogenous (I2 = 0%, P value = 0.933) (Figure 4B)[15-17].

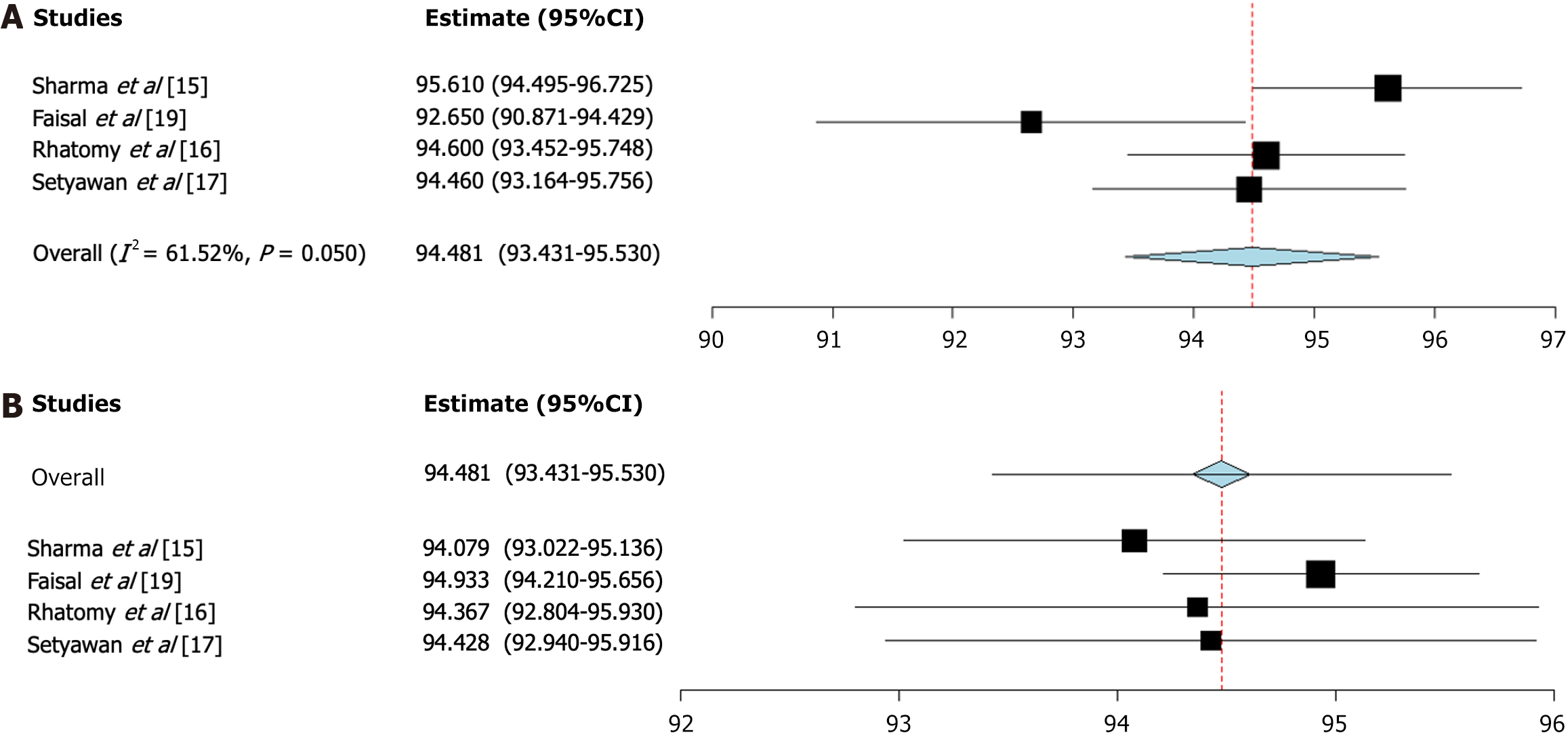

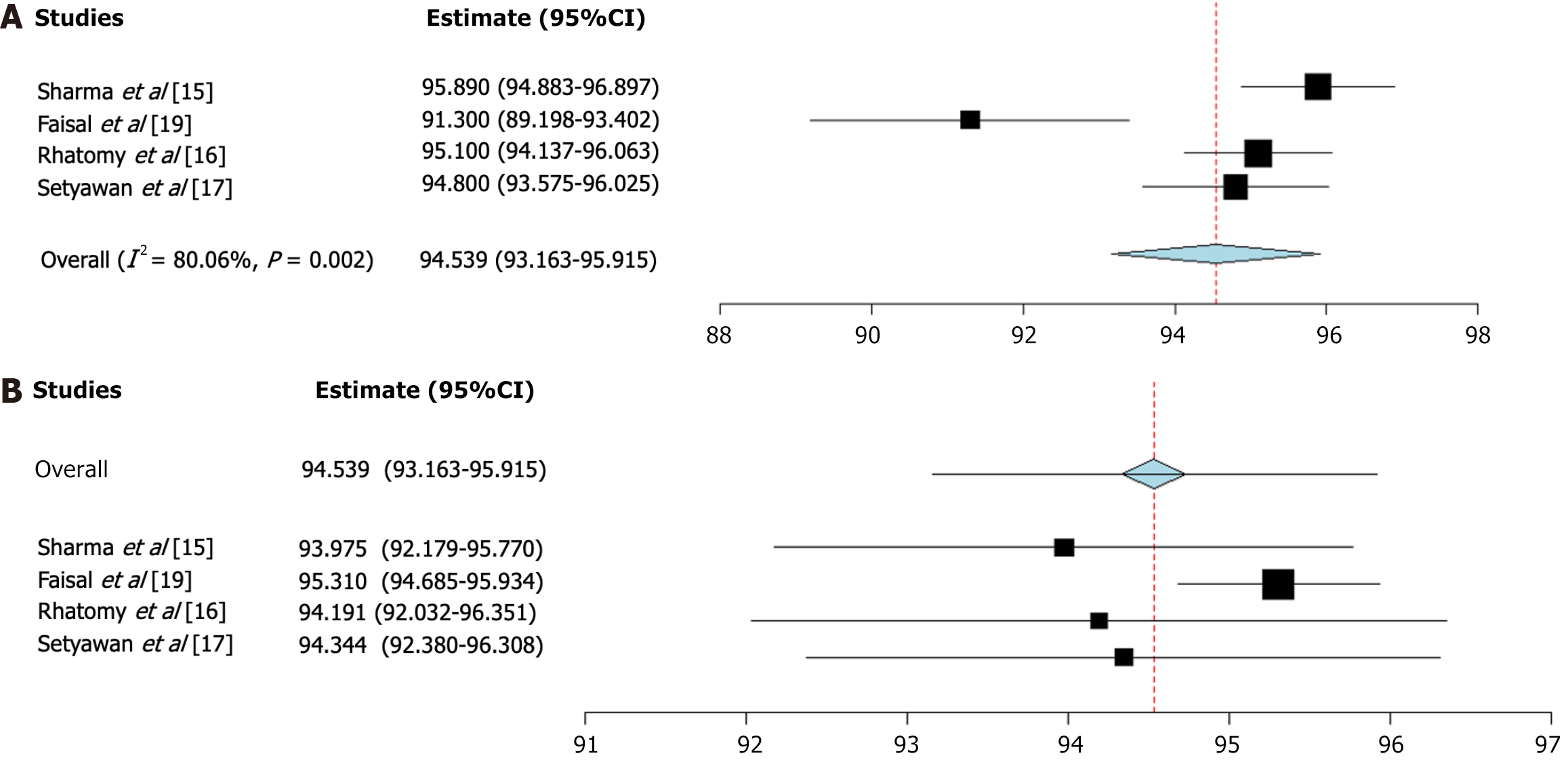

Postoperative AOFAS score after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported by four studies[15-17,19]. The pooled mean of the postoperative AOFAS score was 94.5 with a 95%CI: 93.4-95.5. The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 61.5%, P value = 0.05) (Figure 5)[15-17,19].

Postoperative FADI scores after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported by five studies[14-17,19]. The pooled mean of the postoperative FADI score was 94.5 with a 95%CI: 93.2-95.91. The pooled studies were heterogeneous

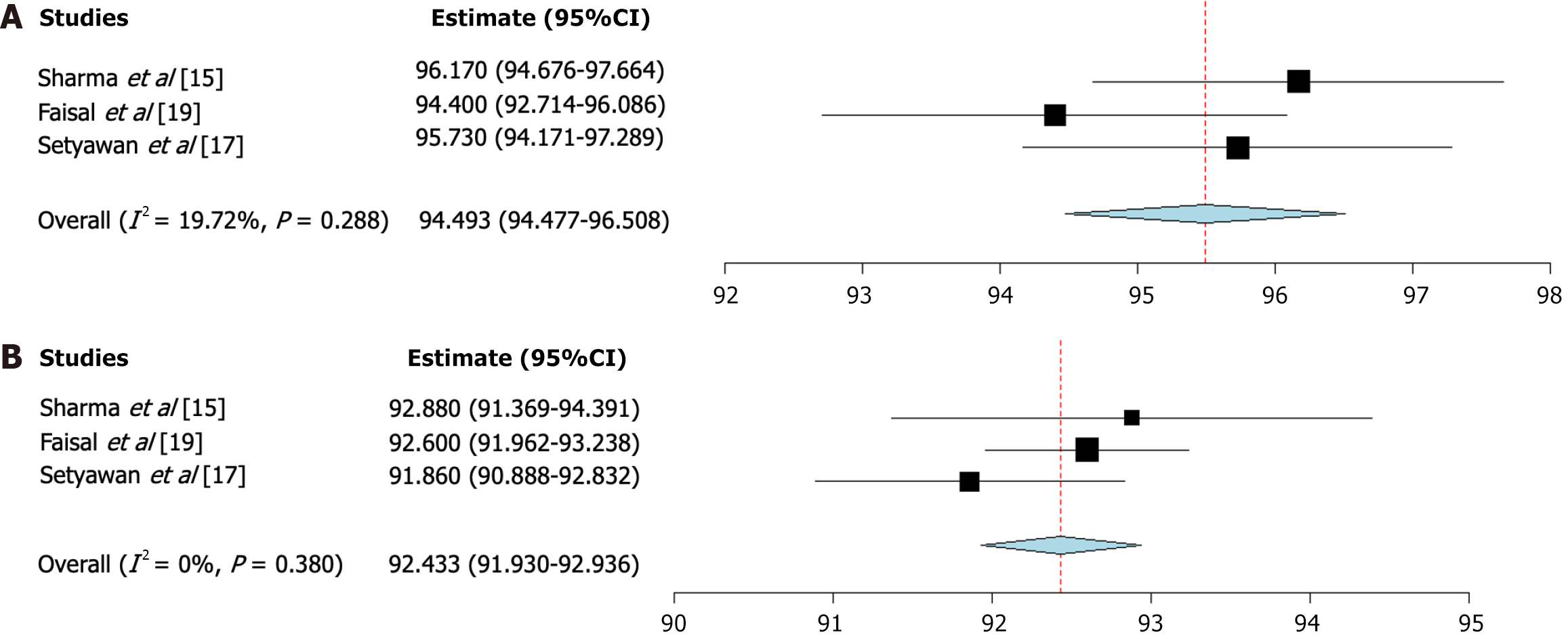

Postoperative single-hop test scores after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported by three studies[15,17,19]. The pooled mean of the postoperative single-hop test Score was 95.5 with a 95%CI: 94.5-96.5. The pooled studies were homogenous (I2 = 19.72%, P value = 0.288) (Figure 7A)[15,17,19].

Postoperative triple-hop test Scores after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported by three studies[15,17,19]. The pooled mean of the postoperative triple-hop test score was 92.4 with a 95%CI: 91.9-92.9. The pooled studies were homogenous (I2 = 0%, P value = 0.38) (Figure 7B)[15,17,19].

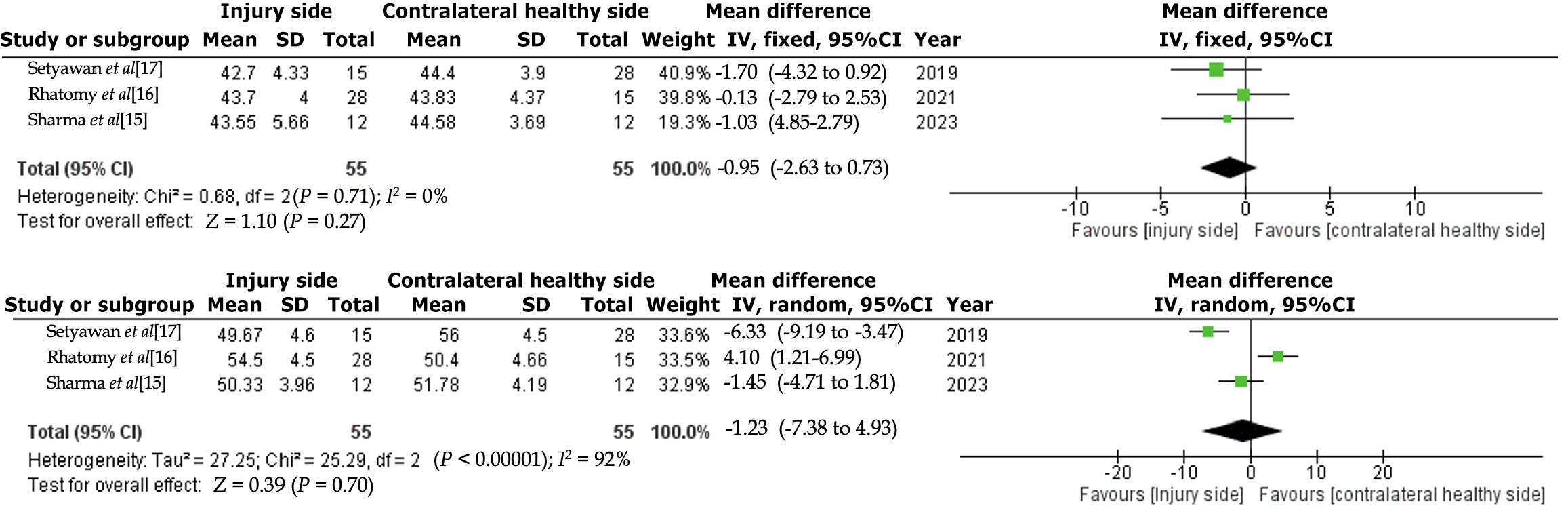

Postoperative thigh circumferences at 10 cm on the injured side compared to the contralateral healthy side following PCL reconstruction with PLT autograft were reported in three studies[15-17]. No significant difference existed between the two groups in the fixed effect model (MD = -0.95, 95%CI: -2.63 to 0.73, P = 0.27). The pooled studies exhibited homogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.71) (Figure 8A)[15-17].

Postoperative thigh circumferences at 20 cm in the injury side vs the contralateral healthy side after PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft were reported in three studies[15-17]. There was no significant difference between the two groups under the random effect model (MD = -1.23, 95%CI: -7.38 to 4.93, P = 0.70). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 92%, P < 0.00001). The heterogeneity wasn’t resolved by the sensitivity test (Figure 8B)[15-17].

Historically, isolated PCL injuries have been managed conservatively, with surgical intervention generally reserved for persistent instability or concomitant ligament injuries in the knee[26]. Chronic PCL insufficiency can modify knee mechanics, and studies suggest that as many as 10% of patients may experience increased arthrosis[27]. Surgical outcomes for PCL deficiency are variable, likely due to the limited number of procedures conducted, the intricate anatomy, and the PCL's continual exposure to posterior gravitational forces at rest[28]. The infrequency of this injury results in limited available data[29], and numerous studies on PCL treatment and outcomes feature small patient cohorts, leading to a lack of consensus.

This meta-analysis evaluated the effectiveness of PCL reconstruction using PLT autograft by examining changes in five validated knee function metrics: (1) The IKDC score; (2) The Lysholm score; (3) The modified cincinnati score; (4) The AOFAS scores; and (5) The FADI scores. The pooled analyses demonstrated significant improvements across all five metrics.

Additionally, postoperative thigh circumference was measured at 10 cm and 20 cm above the knee on the affected side and compared to the corresponding measurements on the contralateral healthy side. This measurement serves as an indicator of the cross-sectional area and strength of the thigh muscle. Three studies[15-17] assessed this parameter and revealed no significant difference between the two groups, indicating similar muscle preservation and recovery.

This suggests that PCL reconstruction using the PLT autograft is effective in preserving muscle mass and strength, indicating good functional recovery post-surgery. The findings indicate that PLT autografts effectively enhance knee function and improve patient-reported outcomes after PCL reconstruction.

Additionally, the scores obtained from postoperative single-hop and triple-hop tests yield significant functional outcomes, reflecting elevated levels of functional performance. Consistent findings across various studies indicate that the autograft derived from the PLT significantly reinstates dynamic knee stability, strength, and endurance, thereby facilitating a functional recovery that approaches normalcy. These findings underscore the graft's capacity to facilitate optimal postoperative knee functionality.

Despite the promising results, the meta-analyses revealed substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, as evidenced by I2 values exceeding 80% for some outcome measures with P-values less than 0.001. High heterogeneity suggests variability in study results, likely due to differences in surgical techniques (e.g., graft fixation, tunnel placement), injury severity, patient activity levels, comorbidities, and rehabilitation strategies.

Autogenous tendons are among the most commonly used graft materials due to their low risk of immune rejection and high success rates[30]. The PLT is being recognized in orthopaedic surgery for its adaptability and robustness and is now being more widely regarded as a promising choice for PCL reconstruction. PLT autografts have become a feasible substitute for traditional graft options like hamstring or patellar tendon autografts, which are frequently employed in ligament reconstruction surgeries. The increasing acknowledgment of PLT as a viable graft option is founded on its anatomical and biomechanical characteristics, which render it appropriate for PCL reconstruction.

Phatama et al[31] performed a biomechanical study evaluating the tensile strength of the PLT, HT, patellar tendon, and quadriceps tendon. The results indicated that the PLT exhibited the greatest tensile strength among the four tendons examined, followed in descending order by the hamstring, quadriceps, and patellar tendons.

The PLT presents multiple benefits as a graft option for PCL reconstruction. In contrast to HT grafts, which are frequently employed[32] but entail considerable disadvantages such donor site pain, potential injury to the medial collateral ligament, premature graft failure, temporary weakness of the hamstring muscles, and anterior kneeling pain[33]. These limitations present considerable obstacles for patients in Muslim and certain Asian nations, where frequent kneeling is a fundamental aspect of daily existence, religious observances, and cultural traditions. Additionally, harvesting HTs requires an incision near the pes anserinus, which increases the risk of injuring the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve[34]. In contrast, the PLT graft mitigates these risks and complications, making it a more suitable option for certain populations.

The harvesting location for the PLT is strategically positioned away from essential neurovascular structures, thereby substantially mitigating the risk of iatrogenic injury during the procedure. A recent study by Nguyen Hoang and Nguyen Manh[35] confirms that the removal of the PLT does not negatively impact the surrounding anatomical structures. The study highlights that the maximum breaking force and diameter of the PLT are comparable to those of other frequently used graft materials, such as the HT and patellar tendon, thus confirming it as a viable and effective alternative. This meta-analysis further emphasizes that the utilization of a PLT graft can result in improved knee functionality and enhanced overall patient outcomes. Significantly, the harvesting of the PLT safeguards the HTs, thereby contributing to the preservation of knee flexor strength and mitigating functional deficits.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Significant heterogeneity diminishes the generalizability of the aggregated findings, while the limited number of included studies constrains statistical power and the capacity to identify publication bias. The meta-analysis depends on published studies, which may introduce bias favouring positive results. Moreover, there was no comparison of the PLT with other alternative grafts.

Future research should prioritize standardizing surgical techniques, rehabilitation protocols, and outcome measures in PCL reconstruction using PLT autografts. This will ensure consistency and enable more accurate comparisons across studies. Larger, randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the efficacy of PLT autografts and compare them with alternative graft options, such as hamstring or quadriceps tendons. These trials ought to focus on clinical outcomes, functional recovery, and patient satisfaction. Long-term follow-up studies are crucial for evaluating the durability of PLT autografts and identifying potential complications, such as graft failure, donor site morbidity, or degenerative changes. High-quality research with rigorous methodologies—such as standardized outcome measures, blinding, and sufficient sample sizes—is critical to producing reliable and generalizable evidence. Addressing these gaps will enhance understanding of PLT autografts in PCL reconstruction and help optimize patient care.

The PLT graft is a reliable and effective choice for reconstructing the PCL, showing notable enhancements in knee stability, functional outcomes, and minimal effects on muscle function, highlighting the dependability of PLT autografts as a surgical alternative. To validate these findings, further high-quality, large-scale clinical trials are necessary to confirm the long-term efficacy, safety, and generalizability of PLT autografts across varied patient populations.

| 1. | Pache S, Aman ZS, Kennedy M, Nakama GY, Moatshe G, Ziegler C, LaPrade RF. Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Current Concepts Review. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2018;6:8-18. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Freychet B, Desai VS, Sanders TL, Kennedy NI, Krych AJ, Stuart MJ, Levy BA. All-inside Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Surgical Technique and Outcome. Clin Sports Med. 2019;38:285-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hopper GP, Heusdens CHW, Dossche L, Mackay GM. Posterior Cruciate Ligament Repair With Suture Tape Augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8:e7-e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Owesen C, Sandven-Thrane S, Lind M, Forssblad M, Granan LP, Årøen A. Epidemiology of surgically treated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in Scandinavia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:2384-2391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bernhardson AS, DePhillipo NN, Daney BT, Kennedy MI, Aman ZS, LaPrade RF. Posterior Tibial Slope and Risk of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:312-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tadlock BA, Pierpoint LA, Covassin T, Caswell SV, Lincoln AE, Kerr ZY. Epidemiology of knee internal derangement injuries in United States high school girls' lacrosse, 2008/09-2016/17 academic years. Res Sports Med. 2019;27:497-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Johnson P, Mitchell SM, Görtz S. Graft Considerations in Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11:521-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan YS, Yang SC, Chang CH, Chen AC, Yuan LJ, Hsu KY, Wang CJ. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament with use of a quadruple hamstring tendon graft with 3- to 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:762-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pinczewski LA, Clingeleffer AJ, Otto DD, Bonar SF, Corry IS. Integration of hamstring tendon graft with bone in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:641-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen CH, Chen WJ, Shih CH. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament with quadruple hamstring tendon graft: a double fixation method. J Trauma. 2002;52:938-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thomas AC, Villwock M, Wojtys EM, Palmieri-Smith RM. Lower extremity muscle strength after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. J Athl Train. 2013;48:610-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18665] [Cited by in RCA: 17544] [Article Influence: 1096.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 15289] [Article Influence: 2548.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kumar R, Kumar M, Sharma AK, Kumar S. A prospective study done to evaluate the functional outcome of knee after arthroscopic posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using ipsilateral peroneus longus autograft. SJHR-Africa. 2023;4:7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Sharma G, Nitesh K, Kumar M, Kumar Rakesh S. Posterior Cruciate Ligament reconstruction with peroneus longus tendon graft: 18 months follow-up. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2022;9: 1753-1759. |

| 16. | Rhatomy S, Abadi MBT, Setyawan R, Asikin AIZ, Soekarno NR, Imelda LG, Budhiparama NC. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with peroneus longus tendon versus hamstring tendon: a comparison of functional outcome and donor site morbidity. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29:1045-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Setyawan R, Soekarno NR, Asikin AIZ, Rhatomy S. Posterior Cruciate Ligament reconstruction with peroneus longus tendon graft: 2-Years follow-up. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2019;43:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shair NA, Sittar R, Khalid M, Tariq A, Abubakar M, Mian MH. Outcome of PCL reconstruction with peroneus longus tendon graft: An experience from a tertiary care hospital of a developing country. RMJ. 2023;48:876-880. |

| 19. | Faisal MA, Chowdhury AZ, Kundu IK, Mahmud CI, Ali M Y, Runa SP, Rahman MS, Sikder MA, Sarker MM, Alim MA, Hossain MM. Evaluation of the Clinical Outcome of Arthroscopic Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with Peroneus Longus Tendon. Int J Nurs Health Care Res. 2022;5. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2024. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. |

| 21. | Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG; on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editor. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. United States: Wiley, 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Wang X, Han X, Shi X, Yuan Y, Tan H. [Short-term effectiveness of arthroscopic single bundle four-strand reconstruction using autologous semitendinosus tendon and anterior half of peroneus longus tendon for posterior cruciate ligament injuries]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2021;35:556-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu S, Lin W, Xu W, Li H. [Clinical study on reconstruction of posterior cruciate ligament with platelet rich plasma combined with 3-strand peroneus longus tendons]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020;34:713-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rhatomy S, Horas JA, Asikin AIZ, Setyawan R, Prasetyo TE, Mustamsir E. Clinical Outcome of Arthroscopic Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with Adjustable-Loop Femoral Cortical Suspension Devices. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:2791-2795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhong H, Jin Y, Wu S, Liu Y. [Study on reconstruction of posterior cruciate ligament with autologous peroneus longus tendon under arthroscopy]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2021;35:166-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cosgarea AJ, Jay PR. Posterior cruciate ligament injuries: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:297-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shelbourne KD, Clark M, Gray T. Minimum 10-year follow-up of patients after an acute, isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury treated nonoperatively. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1526-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Johnson D. Posterior cruciate ligament: a literature review. Curr Orthop Pract. 2010;21:27-31. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Razi M, Ghaffari S, Askari A, Arasteh P, Ziabari EZ, Dadgostar H. An evaluation of posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21:526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ollivier M, Cognault J, Pailhé R, Bayle-Iniguez X, Cavaignac E, Murgier J. Minimally invasive harvesting of the quadriceps tendon: Technical note. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107:102819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Phatama KY, Hidayat M, Mustamsir E, Pradana AS, Dhananjaya B, Muhammad SI. Tensile strength comparison between hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon and peroneus longus tendon: A cadaver research. JAJS. 2019;6:114-116. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cury RP, Castro Filho RN, Sadatsune DA, do Prado DR, Gonçalves RJ, Mestriner MB. Double-bundle PCL reconstruction using autologous hamstring tendons: outcome with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Rev Bras Ortop. 2017;52:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wittstein JR, Wilson JB, Moorman CT. Complications Related to Hamstring Tendon Harvest. Oper Techn Sport Med. 2006;14:15-19. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pękala PA, Tomaszewski KA, Henry BM, Ramakrishnan PK, Roy J, Mizia E, Walocha JA. Risk of iatrogenic injury to the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve during hamstring tendon harvesting: A meta-analysis. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56:930-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nguyen Hoang Q, Nguyen Manh K. Anatomical and Biomechanical Characteristics of Peroneus Longus Tendon: Applications in Knee Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Surgery. Adv Orthop. 2023;2023:2018363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |