Published online Jul 18, 2024. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v15.i7.668

Revised: February 11, 2024

Accepted: May 9, 2024

Published online: July 18, 2024

Processing time: 191 Days and 12.7 Hours

Aseptic acetabular loosening can result from various factors that can be categorized into groups: patient-related, surgeon-related and implant-related. We present a case of a 63-year-old patient who at first underwent a total hip arthroplasty (THA) using a metal-on-metal bearing due to hip arthrosis. Follow-up visits revealed no complications after the procedure. Two years after the THA, acetabular component loosening occurred due to subsequent trauma of the opposite hip, necessitating a revision THA using a ceramic-on-ceramic bearing.

We aim to illustrate a rare case where the primary reason for undergoing THA revision was not only incomplete bone graft incorporation but also improper limb load distribution. Following the revision arthroplasty, a 9-year follow-up visit revealed improvements in all evaluation measures on questionnaire compared to the state before surgery: Harris Hip Score (before surgery: 15; after surgery: 95), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (before surgery: 96; after surgery: 0), and Visual Analogue Scale (before surgery: 10; after surgery: 1).

Opposite-hip trauma caused a weight transfer to the limb after a THA procedure. This process led to a stress shielding effect, resulting in acetabular component loosening.

Core Tip: This article explores a rare case of acetabular loosening following total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to improper limb load transfer after hip trauma. A 63-year-old patient underwent THA with a metal-on-metal bearing, initially showing no complications. However, 2 years later, acetabular component loosening occurred, requiring revision THA with a ceramic-on-ceramic bearing. The study emphasizes the impact of limb load distribution on hip arthroplasty outcomes. Post-revision, the patient showed significant improvement in clinical parameters. This case underscores the need for careful consideration of limb load transfer after THA to mitigate risks of loosening.

- Citation: Domagalski RS, Dugiełło B, Rokicka S, Czech S, Skowroński R, Rokicka D, Wróbel MP, Strojek K, Stołtny T. Bone graft incorporation failure with inappropriate limb load transfer can lead to aseptic acetabular loosening of metal-on-metal prosthesis: A case report. World J Orthop 2024; 15(7): 668-674

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v15/i7/668.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v15.i7.668

Revision hip arthroplasty occurs in approximately 13% of all hip arthroplasty procedures in the United States, and the demand for hip revision procedures is predicted to double by the year 2026[1,2]. There are many potential causes of hip joint acetabulum loosening including polyethylene wear, aseptic and mechanical loosening, pseudotumor, osteolysis around the implant, periprosthetic fracture, infection and bone necrosis[3]. Understanding the factors of hip loosening may lead to better prevention in the majority of instances. Here, we present a case rarely described in the literature: a patient who underwent a hip revision possibly due to improper limb load transfer after a trauma of the opposite hip.

A 63-year-old male patient presented to the Orthopaedic Trauma Emergency Room with severe right lower limb pain in a flexion contraction. He did not associate the occurrence of symptoms with an injury.

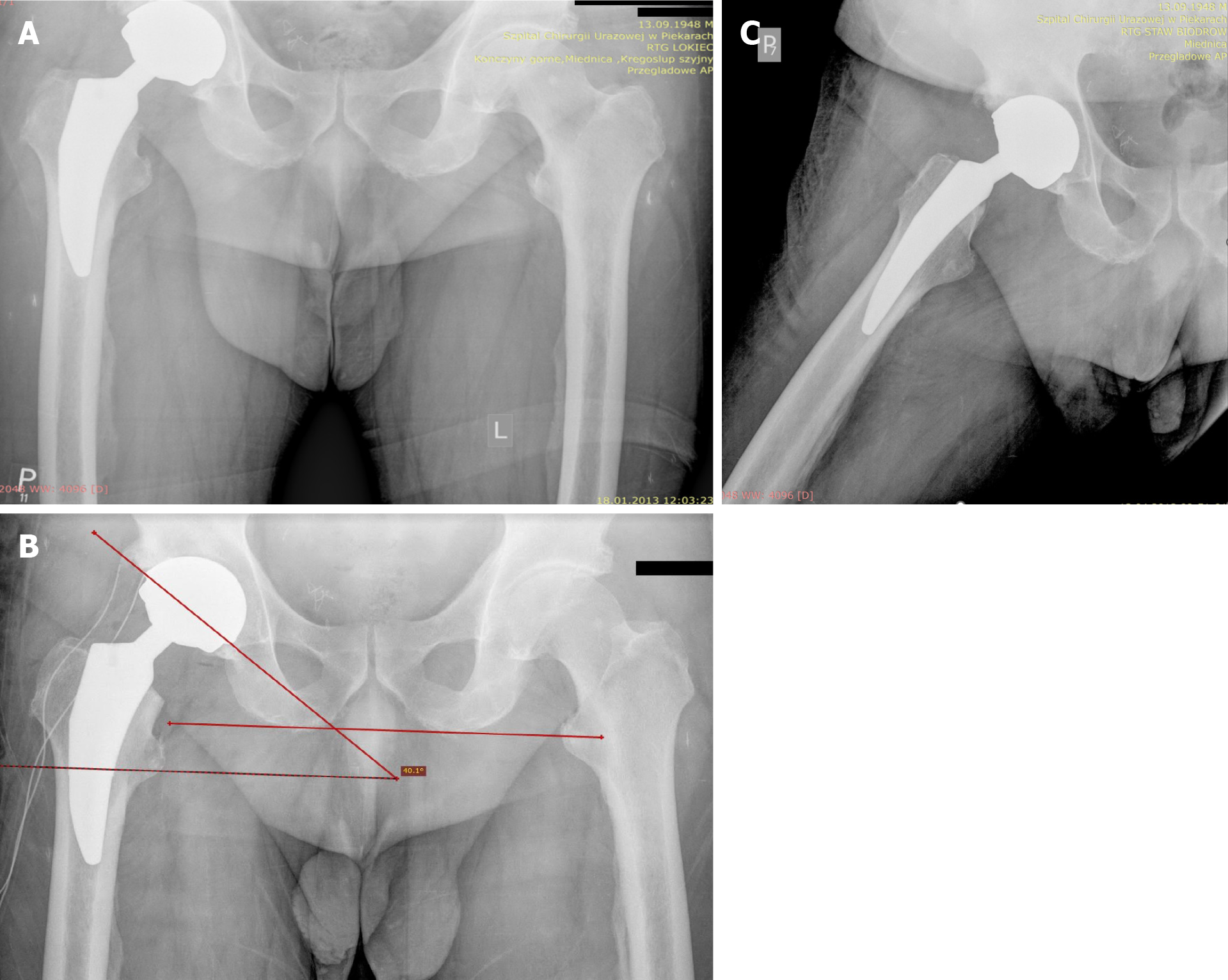

The patient-reported trauma to the hip joint occurred 1 year after total hip arthroplasty (THA) on the opposite hip. However, X-ray imaging revealed no fractures in either lower limb nor loosening of the right hip endoprosthesis (Figure 1A). Seeking relief from discomfort, the patient underwent rehabilitation for the left lower limb. Unfortunately, this resulted in a gradual increase in pain in the right hip joint over time.

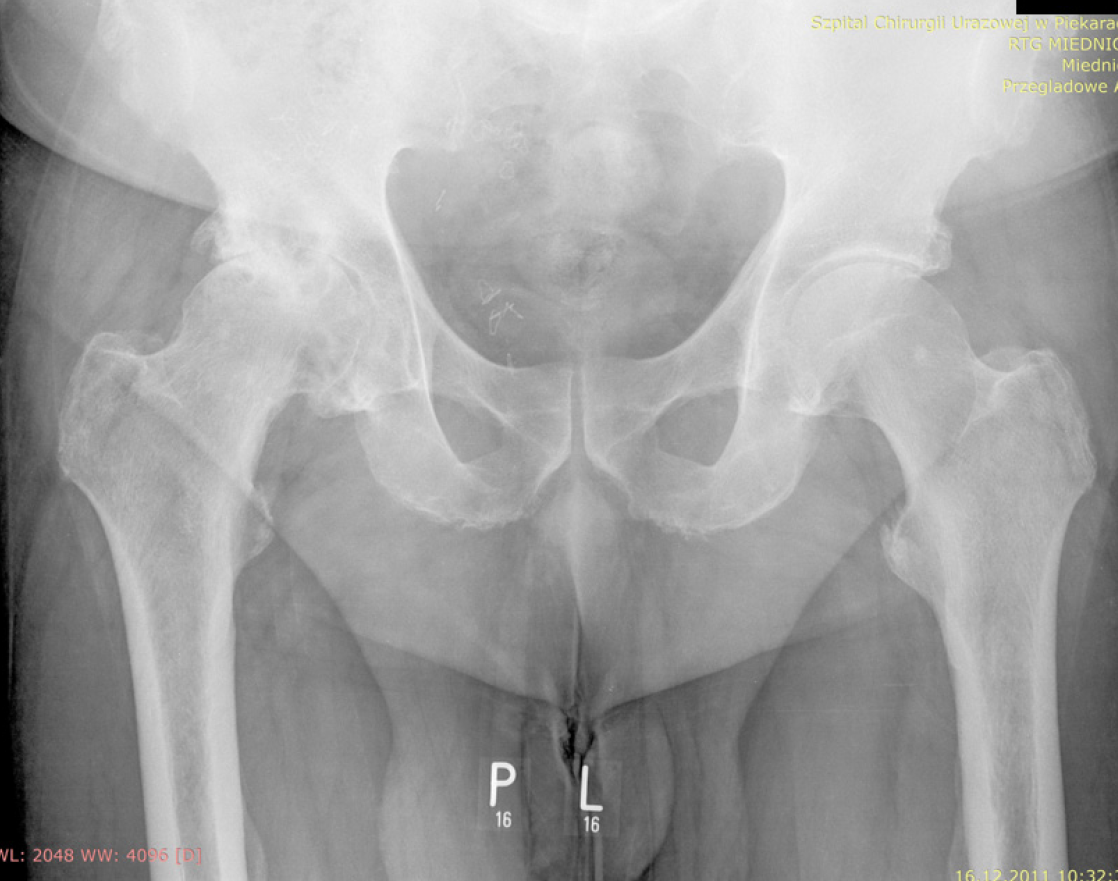

The patient underwent THA due to reduced mobility of the right hip and increased pain especially while walking. Physical examination before the procedure revealed positive Trendelenburg and Duchenne signs. The anti-inflammatory medications had a small impact on pain relief. Using X-ray imaging, hip arthrosis was diagnosed (Figure 2). He was then referred for total hip replacement surgery using a metal-on-metal (MOM) bearing. After 4 months a follow-up examination showed no complications. The inclination angle and limb movements were in the normal range (Figure 1B and C). The patient’s wound had properly healed and he was able to walk without any support.

No significant personal or family history was reported.

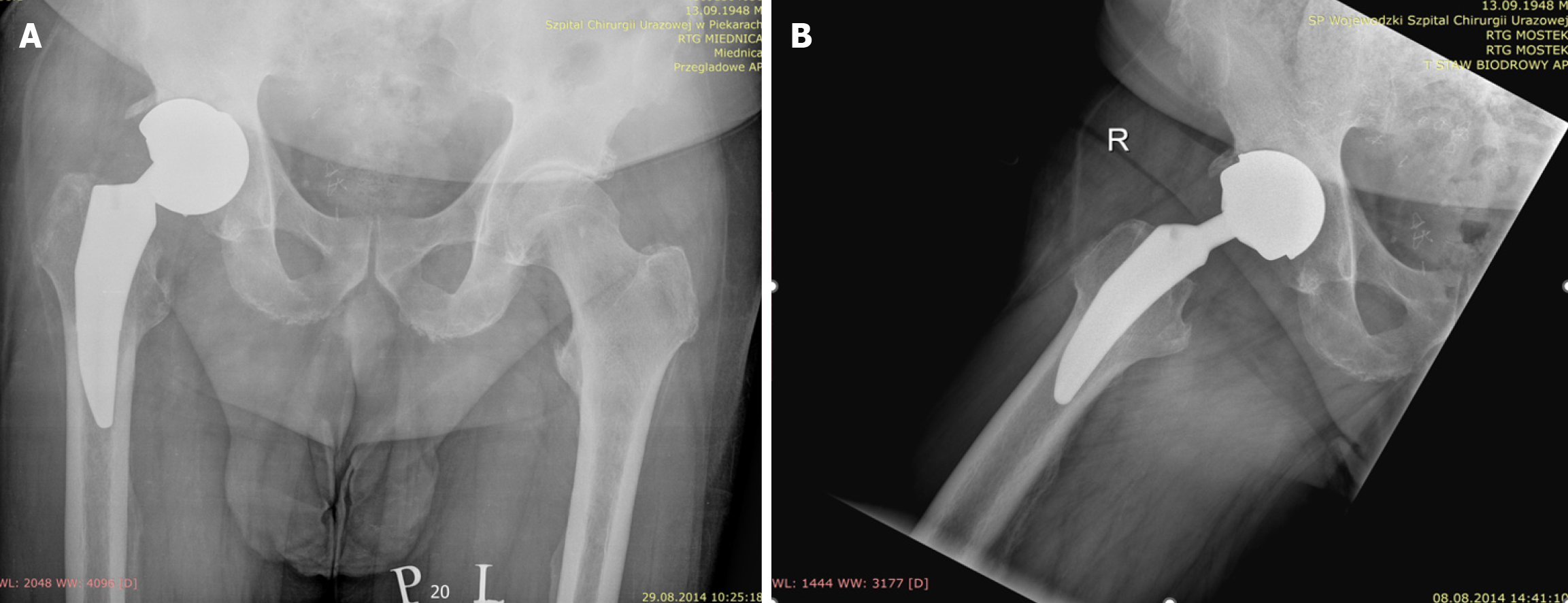

Physical examination showed right limb in a flexion contraction at an angle of about 30 degrees with total right hip endoprosthesis acetabular component loosening (Figure 3).

The patient’s laboratory test findings were within normal ranges.

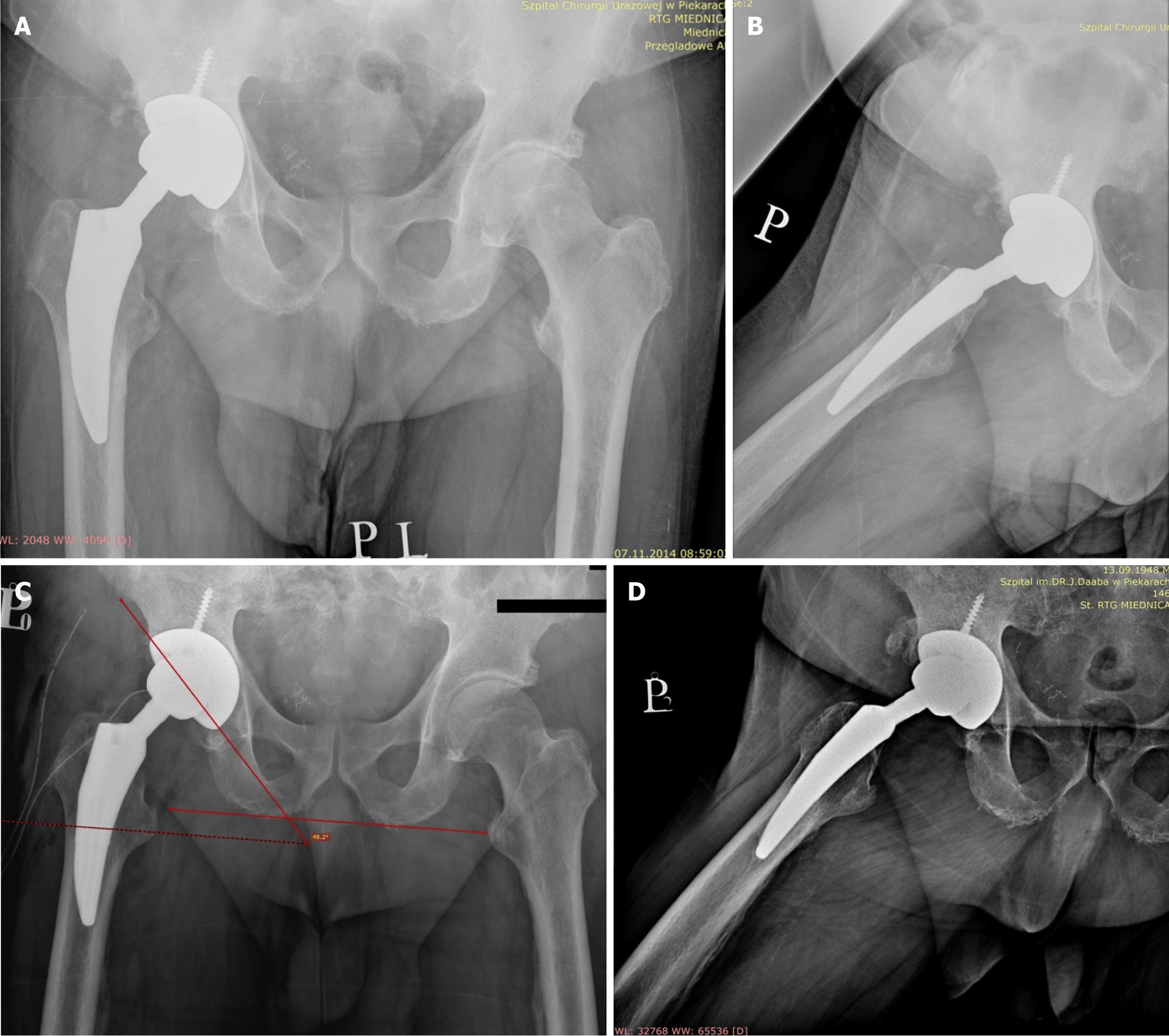

The X-ray images after right hip endoprosthesis acetabular component loosening are shown on Figure 3 and after the revision in Figure 4A and B, confirming the correct positioning of the prosthesis components.

Inappropriate limb load transfer along with failure of bone graft incorporation led to aseptic acetabular component loosening of the right hip joint endoprosthesis.

In 2012, a cementless endoprosthesis of the right hip was implanted using a Biomet Recap-Magnum 54 mm acetabulum and a microplastic metaphyseal stem with a 48 mm metal head. Bone defects mainly around the medial acetabular wall and trochanteric region were filled with an autologous cancellous bone transplantation taken from the femoral head. In 2014, due to the patient’s symptoms and X-ray findings (Figure 3), he was immediately referred for revision arthroplasty of the right hip joint. During the procedure, the cementless Biomet Recup-Magnum system was removed. There was no evidence of metallosis intraoperatively. This time, a cementless 62 mm Biomet Exceed acetabulum was implanted supported by an acetabular screw (30 mm × 6.5 mm) with a ceramic liner (62/36 mm). A decision was made to perform plastic surgery with allogenic cancellous bone from the Tissue Bank in a volume of 20 cm³. A ceramic 36 mm head-cap of the J&J DePuy system (DePuy Synthes, The Orthopaedics Company of Johnson & Johnson MedTech, Warsaw, IN, United States) was implanted. At the end of the procedure, the surgeons observed no hip joint luxation and normal limb movements.

X-ray imaging after the procedure confirmed the correct positioning of the prosthesis components (see Figure 4A and B). The patient underwent rehabilitation in the ward and was discharged with the support of two elbow crutches. After 3 months an orthopedic examination showed negative Trendelenburg and Duchenne signs and a significant improvement in clinical parameters compared to the state before revision arthroplasty. Moreover, a 9-year follow-up visit revealed similar results (Figure 4C and D). The postoperative wound healed correctly by primary adhesion and the patient was able to walk without any support, properly transferring the load between both hip joints. The acetabular inclination angle of the prosthesis before revision arthroplasty was 40.1° (Figure 1B) and after surgery 48.2° (Figure 4C). Right lower limb flexion was at 120˚, internal rotation 20˚, external 30˚, adduction 30˚, and abduction 40˚. The patient scored 5 points on the Lovett muscle strength scale for both limbs, 0 points on Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), Harris Hip Score of 95, and 1 point on the Visual Analogue Scale. All results before and after revision arthroplasty are shown in Table 1.

| Scoring system | Before revision | After revision 9-yr follow-up |

| WOMAC | 96 | 0 |

| HHS | 15 | 95 |

| VAS | 10 | 1 |

Aseptic acetabular loosening after THA is one of the most common causes of both patient and surgeon disappointment, which can occur even when the primary procedure was performed with no complications. All factors can be divided into three groups: patient, surgeon and implant causes. Patient factors include age, body mass index, female sex, patient’s education, level of activity or comorbidities such as infection or aseptic loosening. Surgeon factors include experience and surgical approach. Implant factors include type of alloy, type of articulation, head design and neck or component positioning. Identification of risk factors is difficult because revision arthroplasty is relatively infrequent, with late occurrence[4,5].

Here, we present a case report of a patient who underwent revision THA even though total hip replacement surgery had been performed successfully and follow-up visits 1 year after the procedure showed no complications in physical examination. Consequently, based on clinical data and X-ray imaging, inappropriate weight bearing in addition to inadequate bone graft healing seemed most likely responsible for the mechanical loosening. Due to a trauma of the left lower limb, the right hip joint was severely overloaded, which may have led to a stress shielding effect. It is a process in which bone tissue adapts to increased weight distribution by creating new cells to withstand excessive load and by resorbing bone tissue when it is unloaded. This process is called mechanosensation. Only when the body weight is equally distributed over the limbs will the remodeling be properly regulated. Formation of atrophic bone in the region close to the hip prosthesis can occur when it is no longer physiologically loaded. This process negatively affects the implant’s lifespan[6]. There are a few ways to guarantee proper limb load transfer after a THA and reduce the risk of future hip joint revision arthroplasty. Some manufacturers propose changing the prosthesis design. Larger head sizes have been found to reduce the dislocation rate, shortening the stem may allow more uniform distribution of the load, and using other biomaterials with mechanical features replicating those of the bone tissue such as porous titanium can also reduce the stress shielding effect and osteolysis by 75% compared to traditional implants[7,8].

The other possible cause of our THA revision is the type of bearing. MOM and ceramic-on-ceramic (COC) bearings were developed to reduce polyethylene wear osteolysis. In a meta-analysis by Lee et al[9], MOM showed a higher revision rate than COC, possibly due to a lower wear rate of COC bearings and ceramic particles being more biocompatible than metallic. It is worth highlighting that in our case, the presence of bone defects primarily located around the medial acetabular wall in conjunction with a MOM articulation has the potential to exacerbate the development of a pseudotumor, which could negatively impact the overall results[10].

According to Higgins et al[11], both COC and ceramic-on-metal bearings in 211 patients had the same functional outcomes and radiographic parameters, but the latter had an increased revision rate due to the adverse reaction to metal debris. Moreover, a 20-year follow-up of COC bearings showed that they gave better results in terms of survivorship, complication rate and WOMAC scores, especially among younger patients[12].

In our case, we did not measure the level of metals in blood, but there were no signs of metallosis intraoperatively, which is also a well-known cause of acetabular loosening. According to Crawford et al[13], out of 188 patients with failed MOM THA revisions, the most common causes were acetabular or femoral aseptic loosening, infection and metallosis. Kelmer et al[14] reported that among 535 THA revisions, metallosis was the second major cause of this procedure (95 cases), occurring mostly 2 or more years after the primary THA. According to Stryker et al[15], 107 patients underwent 114 revisions of monoblock MOM THAs, mainly due to metallosis, aseptic loosening or infection.

Within the spectrum of methods available for addressing bone defects in revision THA, inlay bone grafting emerges as a viable and efficacious choice for the restoration of bone integrity and biological reconstruction[16]. One of the causes of acetabular loosening may be improper healing of the bone graft around the acetabulum. In our case, there were no indications for a computed tomography scan, which is a useful method in diagnosing bone graft abnormalities. However, according to our X-ray scans and clinical results, it is more likely that improper limb load transfer led to an incomplete bone graft incorporation and its improper remodeling. We would also like to emphasize the importance of graft vascularization following THA procedures, as achieving adequate vascular de novo development within regenerating bone tissues remains an ongoing challenge. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the COC bearing configuration is bioinert due to less harmful ceramic wear debris, which makes it the safest articulation choice, with a lesser negative impact on bone graft healing and vascularization when compared to the MOM bearing[17].

Furthermore, it is also worth noting that patients of advanced age over 75 years have a higher risk of cognitive problems and muscular tone deficits, which may cause inability to follow the postoperative protocols and increase dislocation rates[18].

Hopefully, further clinical studies revealing new causes of acetabular loosening, technological developments in component design and surgical techniques will continuously reduce the number of THA revision procedures. Due to the long (9-year) follow-up period of our patient, who did not report any trauma or complications after the revision THA, we believe that the most likely factor responsible for acetabular loosening was the stress shielding effect altering bone graft structure caused by inappropriate limb load transfer.

It should be noted that even when the primary procedure is performed without complications, there are numerous circumstances and triggering factors that can lead to a need for revision arthroplasty. In our case, the patient did not exhibit any symptoms or radiological findings, suggesting possible loosening of the acetabular component during the 2-year follow-up. However, most likely due to a trauma to the opposite hip joint, an inappropriate distribution of limb load led to mechanical loosening of the endoprosthesis. Following the revision arthroplasty, an improvement in the evaluation results was observed. These results indicate a significant improvement in the patient's condition after the revision surgery.

| 1. | Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2079] [Cited by in RCA: 3257] [Article Influence: 180.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schwartz BE, Piponov HI, Helder CW, Mayers WF, Gonzalez MH. Revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States: national trends and in-hospital outcomes. Int Orthop. 2016;40:1793-1802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tarazi JM, Chen Z, Scuderi GR, Mont MA. The Epidemiology of Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2021;34:1396-1401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dargel J, Oppermann J, Brüggemann GP, Eysel P. Dislocation following total hip replacement. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:884-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Karachalios T, Komnos G, Koutalos A. Total hip arthroplasty: Survival and modes of failure. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3:232-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Savio D, Bagno A. When the Total Hip Replacement Fails: A Review on the Stress-Shielding Effect. Processes. 2022;10:612. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gómez-Vallejo J, Roces-García J, Moreta J, Donaire-Hoyas D, Gayoso Ó, Marqués-López F, Albareda J. Biomechanical Behavior of an Hydroxyapatite-Coated Traditional Hip Stem and a Short One of Similar Design: Comparative Study Using Finite Element Analysis. Arthroplast Today. 2021;7:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arabnejad S, Johnston B, Tanzer M, Pasini D. Fully porous 3D printed titanium femoral stem to reduce stress-shielding following total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:1774-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee YK, Yoon BH, Choi YS, Jo WL, Ha YC, Koo KH. Metal on Metal or Ceramic on Ceramic for Cementless Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Meta-Analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:2637-2645.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Augustyn A, Stołtny T, Rokicka D, Wróbel M, Pająk J, Werner K, Ochocki K, Strojek K, Koczy B. Revision arthroplasty using a custom-made implant in the course of acetabular loosening of the J&J DePuy ASR replacement system - case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e28475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Higgins JE, Conn KS, Britton JM, Pesola M, Manninen M, Stranks GJ. Early Results of Our International, Multicenter, Multisurgeon, Double-Blinded, Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial Comparing Metal-on-Metal With Ceramic-on-Metal in Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:193-197.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vendittoli PA, Shahin M, Rivière C, Barry J, Lavoie P, Duval N. Ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty is superior to metal-on-conventional polyethylene at 20-year follow-up: A randomised clinical trial. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107:102744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Crawford DA, Adams JB, Morris MJ, Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Revision of Failed Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty: Midterm Outcomes of 203 Consecutive Cases. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1755-1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kelmer G, Stone AH, Turcotte J, King PJ. Reasons for Revision: Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Mechanisms of Failure. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:78-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stryker LS, Odum SM, Fehring TK, Springer BD. Revisions of monoblock metal-on-metal THAs have high early complication rates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abu-Zeid MY, Habib ME, Marei SM, Elbarbary AN, Ebied AA, Mesregah MK. Impaction bone grafting for contained acetabular defects in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18:671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hu CY, Yoon TR. Recent updates for biomaterials used in total hip arthroplasty. Biomater Res. 2018;22:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Miettinen SSA, Mäkinen TJ, Laaksonen I, Mäkelä K, Huhtala H, Kettunen JS, Remes V. Dislocation of large-diameter head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Hip Int. 2019;29:253-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |